In this occasional column, we will invite a respected China writer, scholar or analyst — as well as other public figures — to tell us what’s on their “China bookshelf”. Of course, the very term “China book” (while hardly new, with a history going back to the Jesuit missionaries, Marco Polo and beyond) is as inexact as it is open to interpretation. But we keep a broad church. We are also admirers of physical bookshelves, which readers of books on or from China have been collecting for decades. To that end, we want to know what is on them, how the collection formed, and what interesting titles the collector would like to highlight.

Our first collector is Orville Schell, a sinologist and writer of many books on China who is also co-publisher of the China Books Review. Read our interview with him to discover how his bookshelf was built, and the five books he has selected from it for us.

When did you start collecting books on China, and how did your shelf expand?

I started collecting China books in 1959. I was an undergraduate student at Harvard University, and took the sinologist John Fairbank’s epic classes on Far Eastern History. I’ve remained in China’s force field ever since. I still have those earliest books on China in my library, where despite their cracking bindings, I cherish them as priests might cherish the toenails and locks of hair of the saints preserved in the reliquaries of their great European cathedrals.

I was at Harvard for six years, dropped out twice to go study Chinese in Taiwan, and also spent time in Indonesia during the year of living dangerously. Eventually I went to California to study for a PhD in Chinese History at Berkeley, and brought my books with me. Over the years, they just started piling up.

Where is the collection now, and how do you organize it?

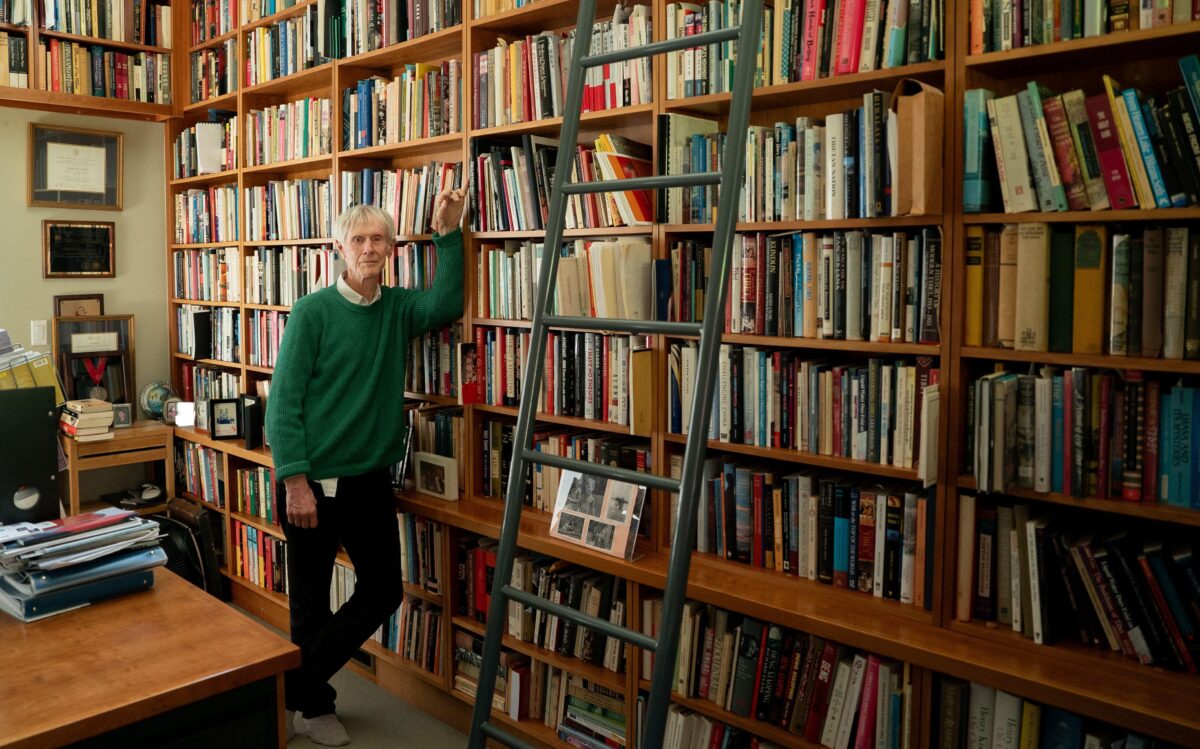

It lives in my home in Berkeley, California, in a purpose-built library study. There are thousands of them by now, I have no idea. In one section, I park the works of those who influenced me most profoundly as I came of age as a sinophile. These include John Fairbank, Simon Leys, Jonathan Spence, Frederic Wakeman, Joseph Levenson, Andrew Nathan, Ian Johnson and Geremie Barmé. The rest are divided into sections for each historical period or topic, including Mao, Deng, philosophy, literature, poetry, democratic movements, foreign affairs, economics, culture and Tibet.

The books go high into the rafters, with thirteen shelves extending about 16 feet up. There is a ladder on rails to help me reach the top ones. For those of us who have too many books, the only answer is altitude. I park the books I don’t want to get at often up high. Two segments there still await my special attention: books by Western Christian missionaries, in which I will someday submerge myself to see what they got right and wrong about China; and books by leftist aficianados of Mao (both American and European) that I want to revisit to see why and how they got the Chinese Communist Revolution so wrong.

The only problem with the ladder is that if I’m walking around in socks, it’s hard to climb up on, as it has rounded, slippery steps. It’s a treacherous journey. But if you were going to go to your ultimate reward, that wouldn’t be a bad way to go.

For those of us who have too many books, the only answer is altitude

What else lives on your bookshelf?

Hundreds of classical music CDs are on shelves to one side. They remain in dust-covered, irrelevant repose as antiques from the pre-Spotify era. There are pictures of my kids, and a quote from Lu Xun: “This is my wish, friend, a journey alone to a distant world of darkness without you, without all shadow. … I shall move into darkness, I shall drift into the land of nothing.” It’s pretty nihilistic. I admire Lu Xun’s infatuation with darkness, because we live in a very dark world.

Orville Schell’s bookshelf picks:

China’s Response to the West

A Documentary Survey, 1839-1923

A John Fairbank book that I still regularly turn to is one he wrote with the academic Têng Ssu-yü in 1954, China’s Response to the West: A Documentary Survey 1839-1923. This is a collection of translations from a wide variety of Chinese works and documents, accompanied by introductions and exegesis. The collection beautifully limns almost a century of Chinese intellectual thinking, in their own voices, towards the outside world. Fairbank was one of my two undergraduate advisors at Harvard. He lived in a funny little colonial wooden house built in the 1700s, and would invite me to tea parties there. I think the whole way I look at China, through the lens of the complexity of its interactions with the West, grew out of him.

In Search of Wealth and Power

Yen Fu and the West

The sinologist Benjamin Schwartz was my other advisor at Harvard. Because it made such a profound and long-lasting impression on me, I want to mention his 1964 work In Search of Wealth and Power: Yen Fu and the West. This wonderful intellectual profile recounts how the 19th century Chinese scholar Yan Fu journeyed to the West, predominantly England, trying to understand why China had become weak while the West was strong, and how China might rejuvenate. It ultimately inspired the title of a 2013 book that I co-authored with historian John Delury, Wealth and Power. Schwartz was a brilliant and singular scholar, whose Talmudic inclinations made him a master at unravelling the inner import of Chinese texts.

Chinese Characteristics

Arthur Henderson Smith was an American missionary, born 1845, who lived in China for decades and wrote several books of which Chinese Characteristics, published in 1894, was the most popular. I first read it many decades ago, and found it both extraordinarily insightful and replete with myriad stereotypes. But then, many works by Westerners of that time, especially missionaries such as Smith who imagined themselves as “bringing civilization to China,” were freighted with such imperiousness. None the less, I’d like to go back now and see in greater detail what Smith got right, and what he got wrong. What did he divine over a century ago that still holds some truth about “the Chinese people” today?

Chinese Shadows

Simon Leys was the pen name of the sinologist Pierre Ryckmans. A Belgian Catholic trained in both vernacular and classical Chinese, Leys had a unique x-ray vision that enabled him to see through the propaganda and cant coming out of early Communist China into the reality of Mao’s revolution. This enabled him to write some of the most trenchant, insightful books and essays on China, starting in the 1970s. His 1974 book Chinese Shadows is the classic, but also look at his 2013 collection of essays The Hall of Uselessness. Leys was also tireless in his jousting with French leftist intellectuals who had a tendency to fall under Mao Zedong’s thrall, and always gave these apologists a good run for their money on French television.

A Curtain of Ignorance

How the American Public Has Been Misinformed About China

Finally, as to those Westerners who drank the Maoist Kool-Aid and extolled his revolution, Felix Green is a good example. A documentary film maker and writer (and cousin of novelist Graham Greene) he wrote A Curtain of Ignorance in 1964, among other hagiographic works, and was a major apologist for Mao’s China. Others include William Hinton, author of Fan Shen: A Documentary of a Revolution in a Chinese Village in 1966. Hinton had worked for the United Nations Relief Administration during WWII, but stayed on in China after Mao came to power in 1949 to write about land reform and the Communist Party’s campaigns against landlords. How, we may now wonder, did some intelligent people fail to see or understand what was actually happening in China under Mao, when others such as Leys saw it so clearly?

Thank you for sharing your China bookshelf with us. Any last words or advice?

Mark your books. Then you can see what your comments were in books that you read fifty years ago. It means that when you go back again, you know your way around them. You are familiar with their geography, because you’ve already blazed the trail. There are roadsigns and notes and underlinings. Books have a strange way, as you get older, of repurposing themselves in your life. You find different reasons to reconnect with them. So it’s good that they’re not virtual, they are actually there. I do read e-books too, but after you finish they vanish into the great beyond. ∎