Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Arthur Kroeber is a founding partner of Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing-based economic research consultancy firm (a subsidiary of Gavekal, a Hong Kong financial services firm for which he is also head of research). He is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings-Tsinghua Center, and author of China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know (2016). In this Q&A, ungated here from our sibling site The Wire China, he discusses the health of China’s domestic economy, its high debt, and the costs of Xi Jinping’s focus on national security.

You have written that the story of the Chinese economy is not a narrative, but a constantly changing 3D jigsaw puzzle. What’s the shape of that puzzle now?

A lot of recent discussion about the direction of the Chinese economy post-Covid has been in the form of grand narrative storytelling. One story is there’s a contradiction between a Leninist political system and a capitalist economy, and sooner or later one of these has got to crumble, which seems to be what’s happening right now. There’s another story that China’s growth has been due to an accumulation of huge amounts of debt over the last 15 years, and now the bill is coming due.

Each of those stories captures a dimension of what’s going on, but people really want that one dimension to explain everything. What’s missing is an appreciation of how relatively ordinary macroeconomic policy decisions are probably having a pretty big impact on how China looks today.

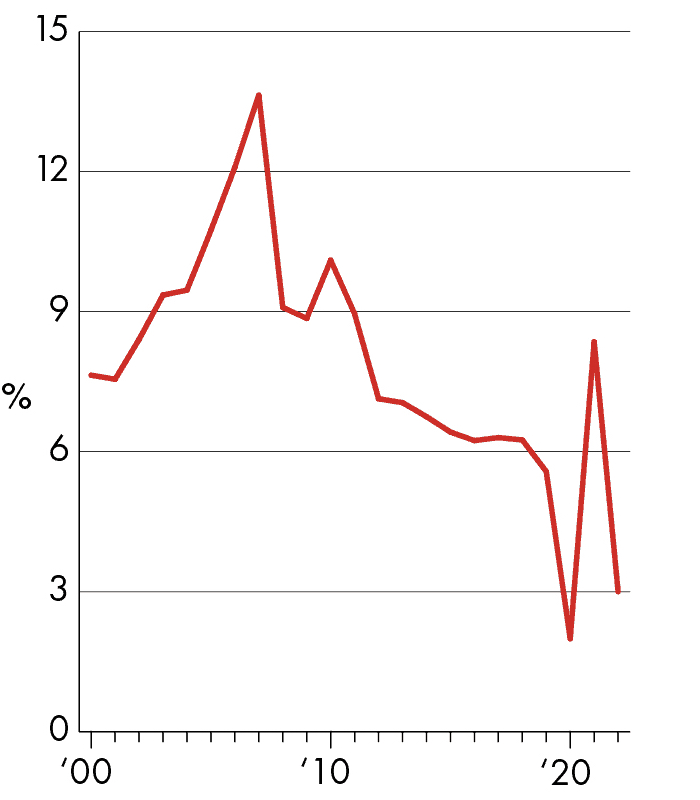

from 2000 to 2022 (The Wire China)

Take household incomes. The U.S. response to Covid was shoving huge amounts of money into household bank accounts. The result was that the total amount of income among American households was substantially higher at the end of the pandemic than it was before — and people felt free to spend that income. When China locked down in early 2020 and 2022, there was no compensation if people lost their jobs or their small businesses closed, with no prospect that this income would come back. So in China, household income was substantially lower than it was before and employment prospects were uncertain, meaning people cut back on consumption, and were slow to bring it back because they wanted to feel more secure. That simple fact accounts for quite a lot of the difference in the recovery trajectory between the U.S. and China.

Also, China’s fiscal spending has gone down. They did a lot of extra fiscal spending through most of 2022. As soon as the Covid restrictions came off, they started reducing fiscal expenditure substantially. There are a lot of prominent economists within China who’ve said the government has overdone it, that they tried to tighten the government budget too much too soon. It seems a lot like the secular stagnation of the U.S. economy in 2012 or 2013, where the U.S. had hit a wall of lower growth because they didn’t stimulate enough. You see similar forces in China today.

So we don’t know, frankly, if the malaise you see in China today is the result of deep structural forces and the triumph of Leninism and so forth, or if it’s simply a bunch of macro-policy mistakes. Both these policies are clearly negative and could be reversed without having to touch any of the so-called structural problems in the economy. What kind of impact would that have on economic growth? It would probably be pretty positive.

You said in a lecture at Harvard in September that you think Xi wants to create a “Leninist Germany.” Can you talk us through what that looks like?

They don’t want to look exactly like Germany, which has quite a generous welfare state, because they’re concerned about the ageing population. If they make a lot of promises about pensions and health care now, these could become unbearably expensive down the road. But they want to have a production structure and a pro-manufacturing bias that looks like Germany.

If you look at China’s economic growth over the last 25 years, the main drivers have essentially been investment and exports. They think promoting investment is more important than consumer demand; that if you make the right investments, this will create successful industries that are very productive. They’ll be able to hire a lot of workers at high wages, and will spawn a lot of service industries that cater to these workers.

A lot of recent discussion about the direction of the Chinese economy post-Covid has been in the form of grand narrative storytelling.

For a long time, the investment priority was in property and infrastructure, but the government is saying that time is now done because those markets are saturated: so they need to redirect capital into technologically intensive industries. And because they’ve focused on creating new supply through production, rather than new demand through consumer spending, they produce more than they can consume, running a trade surplus. That’s a lot like the economic model of Germany, which has never agreed with the Anglo-Saxon idea that you need to have a fundamentally consumer-driven economy. China’s come in for a lot of criticism from the United States for running an economy that has these big trade surpluses, and not supplying enough demand for the rest of the world.

How do you think that reorientation of capital to tech is going?

In some respects, quite well. If you look at the success they’ve had, not just in electric vehicles, but in the automotive industry generally, they are now the world’s biggest car exporter. The majority of that volume is conventional cars, not electric vehicles, mainly going to developing markets in Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East.

They have also done incredibly well capturing huge swaths of the electric vehicle chain, from the basic inputs through batteries to the final assembly. They’ve done very well in every element of the green technology chain, and in things like industrial robotics. Chinese manufacturers now have about a 20% share of global trade in manufactured goods exports. About 20 years ago, they had around a 5% share.

My bet is they’ll keep going and be very successful in this area for a couple reasons. One is that China’s manufacturing ecosystem is very powerful. The traditional view was this was just down to cheap labor, but that is not a part of the story anymore and hasn’t been for some years. You have industrial clusters of companies doing similar or complementary things, building off each other’s knowledge. The logistics and infrastructure for getting these things out of the factory and into markets around the world is very good. The human talent pool is extraordinary — China now graduates about 10 million people a year from tertiary institutions: at the beginning of the century, it was a million. If you want technical talent, if you want engineers, if you want finance people, software programmers, whatever, China offers a vast pool of pretty skilled labor at a competitive cost. All this creates a very strong ecosystem that is very difficult either to dislodge or to replace.

There’s no doubt that right now, there’s a downturn in China. But you can have a manufacturing sector that is going through a cyclical downturn and yet is fundamentally very strong, with underlying competitiveness that is multifaceted and firmly grounded. These two stories can both be true at the same time.

The services sector numbers are quite interesting. It seems like a lot of people in 2022 left low-end service occupations in the cities, went back to the countryside and started working on their family farms. Services employment went way down and agricultural employment, which has been going down continuously for the last 30 years, actually went up in 2022. That’s very unusual.

This is because of the rolling lockdowns throughout Chinese cities in 2022. If you were working in a nail salon or doing delivery or whatever, you just didn’t have any work. A traditional escape route for people in the cities has been to go back to the family farm and hang out there until things get better. You saw this in 2008 and 2009 after the global financial crisis, where 20 million people who lost export manufacturing jobs went back home. Again, we need to be careful assuming particular data points we see now are reflective of some gigantic long-term trend. There’s a lot of reason to think much of what we’re seeing here is delayed impacts of the very severe Covid lockdowns last year, and it’s just taking a lot longer than anyone anticipated to return to normal patterns.

My expectation is that China’s economy is going to grow by 3% or 3.5% per year, rather than the 5% or above we were used to before Covid.

Do we know exactly how much debt there is out there in China at the moment?

No, we do not know precisely. That is definitely a problem, and the authorities have been struggling with this issue. It’s also one of the obstacles to coming up with a full solution, because if you know exactly what the size of the problem is, then you can scale a solution that solves that problem. There is no question that you also have a big set of problems in the debt of local governments and of property developers, and it’s going to take several years to fully get these problems under control and resolve them. While these things are being resolved, this will act as a drag on economic growth — my expectation is that over the rest of this decade China’s economy is going to grow by something more like 3 or 3.5% per year, rather than the 5% or above we were used to before Covid.

A lot of the problem comes from the way they’ve organized the fiscal relationship between the central government and the local governments. The Chinese system is very reluctant for debt to be recognized as a formal obligation of the central government. The central government’s debt level is only about 22% of GDP, which is the same as it was 20 years ago, even though local debt has risen enormously. If they started nationalizing some of the local government debt and taking it on the national balance sheet, that would raise the overall debt of the central government to a fairly high level, but probably still substantially less than the current debt level of the U.S. federal government. But the Ministry of Finance has determined that should not happen.

14th Shanxi Provincial People’s Congress (MOF)

There’s a complicated political economy game going on between central and local governments about who is supposedly responsible for this stuff. Essentially, the central government has said they’re going to force local governments to take a very large share of overall government expenditure, and not allow them to raise the revenues they need to finance this expenditure. In theory, this gap should be made up by transfers from the central government, but the transfer system doesn’t work very well. Local governments incur more debt to finance this expenditure — as well as to finance unrealistic growth targets — even though in many cases the central government knows they don’t really have the revenue to service that debt. In another country, what would happen is the central government would issue a lot of debt, putting it on their own balance sheet, and then transfer the money down to the localities. China has chosen to do it the other way around. That is proving to be an unsustainable system, and they need to figure out how to change it.

What are the main differences between China’s real estate and local government debt bubble today, and what was going on in the U.S. in 2008?

In the U.S., one big problem was that people bought houses with very low down payments, 5% or less, and often used their housing equity as a source of cash for consumption. So when housing prices fell, consumers were a lot poorer and had to cut back their spending.

In China, down payments are a lot higher, 20% or more. So the debt problem is not with households who, unlike U.S. homeowners, are not left holding the bag with houses that are worth a lot less than they paid for. So we don’t really see the property downturn as being a major constraint on households’ ability to spend. It might be a constraint on their willingness to spend, but it doesn’t have an impact in cash flow terms.

The other big difference is that in the U.S. in 2007 and 2008, the entire financial system had gotten so dependent on shadow banking, built around mortgages, that it stopped functioning when the mortgage market collapsed. Up until about five years ago, China was heading rapidly towards creating a similar system. The government wanted to get rid of that, so in 2017 they started a massive crackdown and now the financial structure is much cleaner. The major banks within the system actually are pretty well capitalized, and their exposure to the real estate developers is a lot lower than that of the regional banks. The property sector has had a big debt restructuring problem which is incredibly difficult to resolve, but it’s much less likely that in China you’re going to have a dramatic financial crisis like we had in the United States in 2009. Meanwhile, a lot of other activities which are not related to real estate can essentially keep going on the same way they did before.

There’s a feeling within China from a lot of people that Xi has overreached, he’s needlessly antagonized the U.S., which has created a lot of problems.

Do you think the responses so far from the government to the real estate and local government debt bubble have been enough?

No, they will have to do more. One thing is, they’re going to take these big lumps of LGFV [local government financing vehicle] debt and refinance them or quarantine them, or in some cases make them effectively a central government responsibility.

In the property market, they’re going to have to come up with some better solution for essentially financing the purchase of units that are under construction or completed, but not yet sold in the lower tier markets. There’s a fundamental shortfall of demand. The government has assumed that if they relax enough buying restrictions, buyers will flock back. That appears to be true in big cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, but much less true in smaller cities. They’re going to need to come up with a government source of demand to buy these properties up, ensure they’re completed, and then figure out how to get them onto the market as rental properties.

The bigger issue is that they will need to come up with a better way of organizing the fiscal relationships of central and local governments. A lot of local government revenue has come essentially from land sales, and that’s no longer a viable mechanism of raising revenue. They haven’t really figured out how to tax the country properly. The most obvious way to do that is by imposing a tax on the value of property, which most countries have. But that is politically sensitive in China, because now we’ve had a lot of people who bought property on the assumption that it was not taxed. Saying this tax-free asset is now taxable every year would be very difficult for them.

Looking at the data, you’ve got record capital outflows, along with bad FDI [foreign direct investment] and stagnating domestic venture capital investment. There’s poor manufacturing data, and a lack of confidence in the leadership to maintain prosperity. Are there any precedents to all of these things combined, since reform and opening up?

This is a new situation. FDI is a real problem, because with the flow of foreign capital comes a flow of ideas. If you look at the more innovative companies that are likely to be important in the future of China’s economy, it doesn’t seem like a lack of capital is really the problem. There’s enough domestic money to finance whatever China needs to do, but the dynamism of China’s economy that came from this influx of foreign ideas is being lost.

The level of concern about the political leadership is just a question of basic competence. Are the economic officials today up to the challenges of managing this economy? There are plenty of people inside China who say the level of competence of the senior economic officials has gone down. If you look at the new team that Xi has installed, it has many fewer people with any kind of international experience or experience of running things at the national level.

There is also the question of overall political direction. 15 years ago, MIT’s Yasheng Huang coined the phrase “directional liberalism,” which tried to explain why in the 1980s and 1990s private entrepreneurs invested when there was basically no legal system in China, meaning there was nothing to stop the government from coming in and stealing it all from you. The answer was that there was a very clear signal from the top that the overall direction of the country was towards more liberalization. Even if things were imperfect today, you could bet that five or ten years down the road, the situation would be more favorable.

What you now have is “directional illiberalism.” It’s clear that under Xi Jinping we are heading towards a state that is more controlling, that is much less concerned with economic growth, much more concerned with security. When you hear people in the private sector express worries about China, this focus on security over growth concerns them.

However, there are a couple of things that we need to put against these concerns. If you look at the data on private investment in manufacturing, it is not weak. It is, in fact, very strong. You can definitely talk to entrepreneurs who will be negative, and yet look at the numbers and they don’t quite tell you the same thing. What that tells you is people are still moving ahead with a lot of opportunities in various sectors. If you are making the next cancer drug or industrial robots or clean energy equipment, it’s not clear that this sort of directional liberalism is all that important, as long as the markets for those goods are allowed to function, which basically they are.

A lot of people I’ve talked to suggest there’s a split in private sector opinion between age groups. Older people who made their money under the prior system are extremely negative — from their perspective, conditions now are a lot worse than they were ten years ago. But if you’re younger and you still have yet to make your pile, you’re more focused on what opportunities there are in the world as it exists now. A lot of the discussion in the media has focused on the first group, as they’re easier to get to, not so much the second.

15 years ago, MIT’s Yasheng Huang coined the phrase “directional liberalism.” … What you now have is “directional illiberalism.”

The leadership seems to be responding to the current economic crises by increasing controls on localities. Do you think that risks one of China’s main economic drivers?

The advantage of this traditional system was that you had a lot of local experimentation and a lot of bottom-up dynamism. The disadvantage was that the system as it developed, up to about 2012, was a breeding ground for corruption. It is important to recognize that when Xi came to office in 2012, he had a specific mandate to rein in the corruption he and a lot of other people felt was devouring the system from within. Some aspects of the centralization and control agenda are part of an effort to create a less chaotic system.

The decentralized model also created [too much] duplicative capacity. As every city in every province wanted to have its car manufacturers, the result was that you had 200 car manufacturers in China. At a certain point, the question becomes how much of that is dynamic, and how much of this is creating massive waste and inefficiency. It’s perfectly normal for there to have been a shift in China away from this “everything goes” mentality to one that imposes more structure and order. You can see similarities to the progressive era in the United States in the 20th century, where there was a lot of federal regulation that was put on top of industries.

What remains to be tested is how flexible Xi is going to be in adjusting, given there’s now a lot of evidence from this year that the current economic policies are just not working. It’s fair to assume he’s security oriented and he continues to move in that direction. But up until this past year, although there were problems, you could make the case that China’s economy was doing quite well overall. From 2012 when he took over, right up until the pandemic, you had growth rates that were running 6-7% per year. For ten years, he was able to run a system under which security was continuously being tightened, without that big of an economic cost.

We are now for the first time in a situation where the costs of the strategy are becoming clear. So now it’s time for him to show his colors. Does he say, “I don’t care, security über alles, if I’m getting enough semiconductor plants built, then that’s fine if we only grow by 1%.” Or does he say, “actually, I need to make some adjustments.”

Left: The 1st World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention (WCEC), 1991. Right: The 16th WCEC, 2023 (WCEC)

What policies would indicate to you that Xi had decided on one way or the other?

It’s not so much what they do on the economic front, it’s a question of what they don’t do on the security front. I think the “tightening security” rhetoric and actions that’ve been going on for months and years is now being contained. There is a clear signal that economic growth and development is being reprioritized. The willingness to increase the fiscal deficit is positive.

The other thing that is very important is a stabilization of relations with the United States. There’s a feeling within China from a lot of people that Xi has overreached, he’s needlessly antagonized the U.S., which has created a lot of problems. If you could get a more stable relationship with the U.S. and more growth-friendly policies, that would show Xi was essentially tacking slightly closer to the traditional pragmatic leadership style. They have to do things that show concretely they want to push for a higher growth rate.

Do you think it’s still possible for the Chinese economy to surpass the U.S.?

Oh, it’s certainly possible. If you had a significant change in political direction, which basically means that Xi Jinping had a heart attack tomorrow, and you had a reorientation of government policy and probably more attention paid to figuring out how to increase the vibrancy of the consumer sector. Then China could grow easily by 5% a year for another decade, in which case it almost certainly would surpass the United States. But under the current leadership I think it is more likely China won’t catch up. ∎

Header: KUKA robotic arms work on the assembly line of Chinese EV startup Leapmotor’s C11 electric SUV at a factory in Jinhua, Zhejiang, in 2023 (Hu Xiaofei/VCG via Getty Images).

Alex Colville is a researcher at the China Media Project, currently based in Taiwan, whose work has appeared in The Financial Times, The Economist, Foreign Policy and The China Project among others.