Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

This is an episode of the China Books Podcast, from China Books Review. Follow us to listen to the pod on your favorite platform, including Apple Podcasts and Spotify, where a new episode lands on the first Tuesday of every month. Or listen to this episode right here, where we also post the transcript.

The Cultural Revolution was the most bewildering epoch in a century of Chinese cataclysms. Starting in 1966 and ending in 1976 with the death of Mao Zedong and his successor’s arrest of the Gang of Four, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was a decade of … what exactly? It can be difficult to make heads or tails of the factional conflict, student movements, ideological brawling, red terror, near civil war, succession intrigue, mass rustication and destructive rampage that defined Mao’s last revolution.

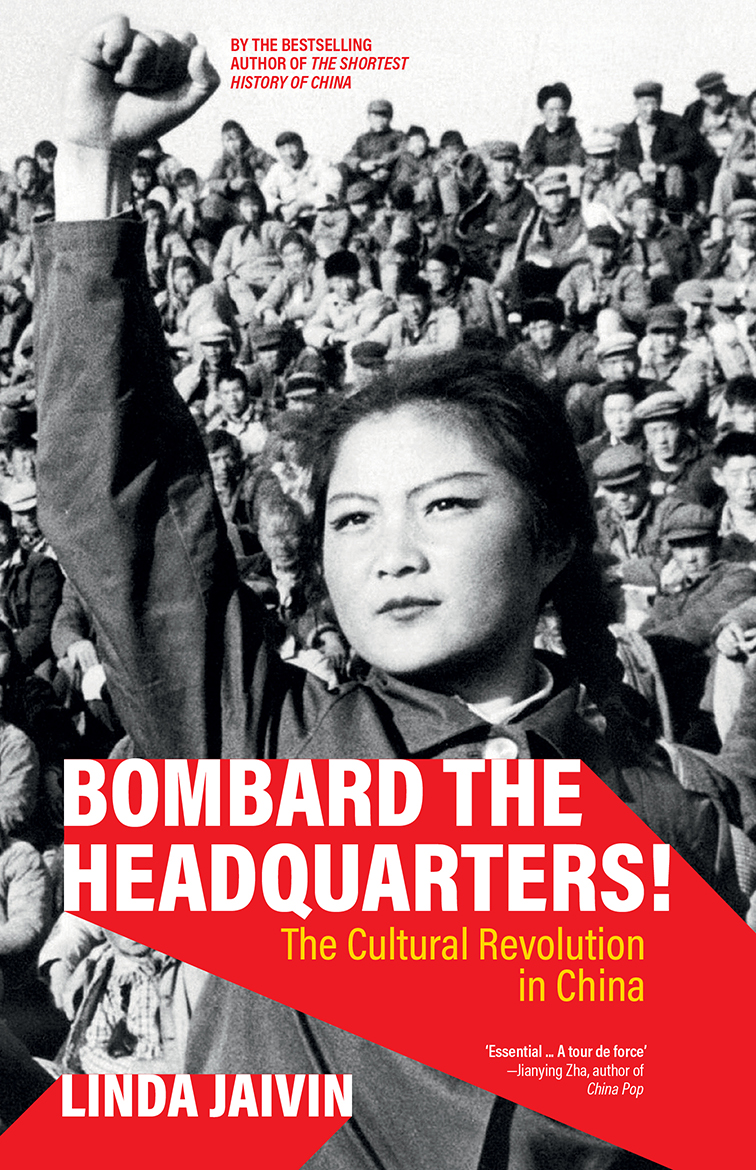

Our guest this month is Linda Jaivin, the writer, translator and Sinologist, whose latest work Bombard the Headquarters!: The Cultural Revolution in China (Old Street Publishing, April 2025) is a little red book that can help us understand how the world turned upside down. In a mere 128 pages, Jaivin untangles the mess of that dreadful decade. We were so pleased to have Linda Jaivin on to discuss her writing career, the Cultural Revolution, its relevance to Xi Jinping’s China, and whether Donald Trump’s MAGA movement has anything in common with Maoism.

Guest

Linda Jaivin is an Australian author, cultural commentator, essayist and translator. She is the author of 13 books — seven novels and six works of non-fiction, including The Shortest History of China (2021) and Bombard the Headquarters! China’s Cultural Revolution (2025). She lives in Sydney on the unceded land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation.

It’s not just outsiders saying, ‘Oh, look at Trump. He’s like the Cultural Revolution.’ It’s actually Chinese thinkers also saying that.

Linda Jaivin

Transcript

Alexander Boyd: When did your interest in China begin? When was your first trip and what was it like?

Linda Jaivin: My first trip was in 1979. After I graduated, I was living in Taiwan for two years. And it was a very different time. It was during martial law and all of that. It was very interesting. But China was just beginning to open up.

So this was ‘77 to ‘79, and then I went to Hong Kong and where, it could be closer to the action. And I went to China for the first time. I took a day trip to Guangzhou. I remember going over there on this tour. When I got there, I managed to detach myself from the group. And two funny things I remember very clearly from that day. One was, I was thirsty and at the time there was the orange drink. China didn’t have a lot of choice. And so I went to get one of these things at a little window shop. And I went over there and it was on some street in Guangzhou. It wasn’t super crowded. Everybody was wearing what we call the Mao suits. We know better, but, called the Mao suits. And there were hardly any foreigners in China. There really were not a lot. I took my drink and I turned around and I had a hundred people around me, And they start discussing me. And of course most of it was in Cantonese, but I was living in Hong Kong, so I got a little bit of the Cantonese. Anyway, it was hilarious. They were just like discussing me. And when I started to speak to them in Mandarin, little effort in Cantonese, they just stared through me because they couldn’t comprehend that I would actually be talking. Do you know what I mean?

Yes.

That was one of my one of my memories from that trip. The other one, which is really great, was I went to I think it was called People’s Park at the time. I dunno.

Safe bet, it’s probably People’s Park.

Probably People’s Park. Let’s just call it People’s Park.

And I thought, I’m gonna have a little walk in this park. So this guy probably about my age, twenties, early-twenties comes up, and he says to me in Chinese, “Do you speak Chinese?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Oh, may I walk with you?” I said, “Of course.” I thought, “Ooh, this is fun. This is interesting.”

You’re not supposed to be able to talk. At that time it was not legal. The only people you could talk to and who could talk to you were authorized people and he wasn’t, clearly, authorized. Anyway we start walking and I’m so excited. I’ve got my first Mainland, real Mainlander, real Mainland person.

I’d met some in Hong Kong. They’re usually dissidents or people out there on some mission or another. Anyway I said to him, “So what do you do?” And he said, “I teach Marxism-Leninism-Maoism” at high school. And I thought, “Oh my God, I’ve totally hit the jackpot here.”

You couldn’t be more excited.

Exactly. So we start talking and I’m asking him about his work and he’s asking me about Hong Kong and about other places and all this stuff, and we’re walking along. I think he was excited. I was excited. And there’s a hill in the middle of the park, and so we climbed up the hill and then we sat down on a bench and at that point he threw himself on me and tried to stick the tongue in and I pushed him off.

I was just like, holy shit. I pushed him off and he said, “Will you marry me and get me outta here?”

Oh my God. And this is your first trip to China.

Yeah.

Unbelievable.

I know. It was, you know, a perfect introduction to what travel writers always called a land of contradictions.

A Marxist-Leninist-lecher. So that is absolutely fascinating. So that is 1979 in Guangzhou?

Yes.

Then did you spend the next decade in China? How did that next book come about, New Ghosts, Old Dreams (1992)?

That was 1992 that we published that. But the way it came about was, I met Geremie Barmé in 1981. I was living in Hong Kong, but I was traveling all the time to China. I was traveling up and down. I got a job with Asiaweek magazine and I was covering China and Hong Kong for them.

So I was always on a plane or a train. Geremie and I were very good friends, then we became more, then we got married. The book we worked on while we were married; it came out, I think, just as we were divorcing. But it’s all part of a time.

And we were prompted by what happened in 1989. A lot of instant Tiananmen books were coming out and it was all about Wang Dan and this and the heroes of the Square and all this stuff. And we wanted to go a lot deeper and we wanted to use Chinese people’s perspectives to make sense of this incredibly heartbreaking thing that had happened.

And we used contemporary sources. We gathered a lot of that. But we also, because Geremie is such a good classical scholar, we brought in a lot of classical literature bits and pieces of it, excerpts on things that talked about the cycles of history that talked about things like restrictions and bindings.

We had Lu Xun in there. We had his brother Zhou Zuoren, who was talking about seeing a demonstration get broken up by police. And so we had a lot of wonderful material, which we translated. We got other people to translate parts of it. We wrote bridging introductions to it.

So it’s now out of print and if any listener can find a copy, I’d say grab it, because it really is a resource and it’s not about us thinking we’re so great. It’s about the amazing Chinese voices, the rebel voices over time that we managed to put together and translate.

Yeah, I second that. It’s a really fascinating work. And as you say, it’s completely different from the host of other Tiananmen books that came out in the 1990s and afterwards. Listeners go to your library and bang on the door if they don’t have a copy, until they get one.

One question that I actually had looking at your writing career; Afterwards, you pen a series of books, both novels, mysteries, and reported works on various themes of erotic obsession. And I was wondering, did China’s 1980s and the protest movement of 89 influence those books? Or how did being in China in the 1980s maybe impact that later writing work?

That’s a really interesting question. I think that there’s two aspects to it. China in the 1980s was so extraordinary, the energy in society, and a lot of it was creative, it was intellectual, it was sexual. People were exploding out of the boundaries and restrictions that had been imposed on them during the Cultural Revolution, which of course there was sex during the Cultural Revolution, but it wasn’t supposed to be happening.

And people were reclaiming that. It was just a wonderful time to be alive, it was very exciting. And then, of course, 1989, and that was so devastating and so traumatic even for those of us who weren’t Chinese, but we had so many friends who were thrown in prison and there was such agony, trying to find out whether your friends had survived. Anyway, it was such a deeply traumatic time, having followed the protests, having been on the square a number of times, seeing the students and so on that I couldn’t really deal with China for a little while. And I moved to Sydney and instantly found all the fun there because Sydney in the nineties was super fun.

And I just plunged straight into it. And yeah I started writing erotic fiction for myself, I was writing little bits of pieces of erotic stories because I’d read erotica that I’d liked so many times and couldn’t find other erotica. And I was like, why didn’t anybody make funny erotica. Sex is hilarious, right?

It is. And it’s much better if you can actually write about it.

Exactly. And I was like, I need the women’s perspective and I need comedy, and I was tired of male perspective erotica. And anyway, so I just started to write some to amuse myself. Showed it to a friend and she said, oh, have you ever heard of… It was an Australian magazine for women that had centerfolds of men.

Oh, no way.

But it was also an intelligent magazine. You could read it for the articles.

So she said, why don’t you send it to them? So I did a little bit of editing and I sent it to them, and then a publisher approached me and said, do you have a book length essay in you about China? And I said, yes, but I also have a pornographic feminist comic novel in me as well. We always joked about this afterwards. I always said he fell off his chair. He said he didn’t. And that’s how my book Eat Me (1998) was born.

And suddenly I was an erotic writer, it was funny. And also we had planned or expected that the book would sell a few copies and then I’d go back to my serious work and instead it went completely nuts and went international and was on the bestseller list in Australia for seven months and it was on independent bestseller, independent bookshop, bestseller list in America. It was a bestseller in France. I was flown over there to be on a big TV show, and I was, I would walk into the Metro and people would say, oh, l’écrivain, the writer. It was just, it was insane. It was really insane. And so I was quite happy because it was a break. It was good. But eventually China pulls you back.

It does pull you back. And that probably should bring us to what we’re here for today. You’ve written a number of China books since then. But Bombard the Headquarters! is the second of your short histories, I believe, right? After 2021’s terrific The Shortest History of China. My question for you is what do you hope to inform people about the Cultural Revolution that you feel is lacking in popular awareness?

I think history has taken a real blow in the social media age. Postmodernism in general just mixed everything up. And I think that we don’t have a real sense of how important it is to know about things like the Cultural Revolution in which, by official estimations believed conservative, 1.7 million people died.

An incredible number of people had life-changing injuries. A whole nation was traumatized. That has consequences that carry on to the present day. I think people can talk about intergenerational trauma, but they don’t get that’s actually something you have to know about China as well to understand China.

And that whole period is at risk of being lost more than certain other aspects of world history because China has done so much to bury it. So what we have is a tremendous literature, which I was able to draw on by scholars, ranging from Roderick MacFarquhar to… There’s so many people who have written about the Cultural Revolution and written about it so well and so deeply.

But those books are pretty much read by specialists. And so I thought what I want to do is do something that has enough narrative drive and intrinsic interest that maybe even high school students, could pick it up, definitely could be something that you could read as any kind of general reader and get a good idea of what happened then and what effects it has on China today.

And it also gives you a lot of insight into how certain things work when you have megalomaniacal authoritarians in charge. And I think that maybe back in the seventies or eighties or nineties or even two thousands you would never think that it would give you interesting lessons on America today, but it does.

But it does, and we will get to those lessons later in our conversation. So one thing that I found very interesting is the recurring focus on gender throughout the book. China today presents itself as an equalitarian country. However, there’s been great reporting about how women are basically systematically excluded from leadership positions in the Communist Party. And throughout the book, you have details about the iron girl aesthetic of female Red Guards who are passionate only for the revolution. You have things about the sexual assault experiences of sent down female zhiqing, whoare the educated youth, and then I think one of the most interesting conclusions that you include in some marginalia, which is a charming feature of this book that allows you to slip in some editorial voice without losing narrative flow. That one conclusion that many drew from the Cultural Revolution was that it’s always a woman’s fault. That the scapegoating of Jiang Qing was effective in that many people started to compare her to Cixi, the last Emperor Dowager of the Qing.

So my question is, how did the Cultural Revolution change China’s society’s perceptions of sex and gender? And do those changes or negative impacts, or positive impacts in some ways? Who knows? Do they persist today?

I think we have to go back before the cultural revolution and look at the language that occurred around the time of the Tang Dynasty when we had Empress Wu. And even before that in the Han Dynasty when an empress dowager also had a lot of power. I can’t remember, it was the Han or the Tang when people started to say that “A woman in power is as natural as a hen crowing at the dawn.”

And so there’s always been this really big prejudice against the idea of women being in power. If you put a woman in power, it’s not only unnatural, it’s going to bring about disaster. The whole history of Empress Wu of the Tang completely ignores, generally speaking. What people know about her is bad. And she slept with these two brothers and she did this and she did that. And if an emperor slept with only two sisters, they’d be pretty much a monk.

but she was actually a very smart administrator and she did a lot of things. And Cixi as well is a very complex character. But the general views of these women in power is negative. Patriarchal views die hard. Now, of course, the Communists came out of the May 4th Movement. Pardon me going so far back in time, but I’m just, I think it’s

No please, this is what we are here for. This is the whole point of the podcast.

Excellent. So the May 4th Movement and the Hundred Days Reform of 1898 that preceded it, the thinkers really valued women’s rights and women’s equality. They were very critical of arranged marriage, which had its harshest toll on the women — athough men didn’t like it either. Yeah, a lot of men didn’t like it, but it was disastrous for many women. And there was a lot of talk of women’s rights. Bertrand Russell traveled to China with his partner Dora Black, I think. And she was a very strong feminist and she was interviewing Chinese girls. She was talking to Chinese girls and students at universities and schools and she said that they were as alert and as awake to these issues more so than any European she had met. It was really strong at that time. Now the Communist Party came out of that.

As you wrote, even Mao Zedong, right, in one of his first essays, “The Suicide of Miss Zhao,” he appropriates a woman’s voice to describe the injustices inflicted upon Chinese women.

Exactly. “They treat us like play things,” he said. And then of course, Mao treated a lot of women like play things.

But it was always part of the rhetoric. Now the whole thing about “women hold up half the sky,” as I wrote in the shortest history of China, comes from a very specific story, which was in 1956. They were pushing forward collectivization across the country and men earned far more work points for a day’s work on the farm than women. So there was this one village and the village there were, I, there weren’t that many people in this village, but the women were just like, yeah, screw that. I’m gonna stay home. Why would I work all day and get so few work points?

So the men were going out in the field and the women were staying home for the most part. And the woman who was the cadre, the Party cadre in charge of women’s work said to the village chief, “What if we gave women equal pay for equal work? Let’s try it.” And you know how communism works in China is very often people think of it as all centralized, top down, but you get these, what they call jingshen (精神) or spirits of the thing coming from the top and guidelines. But very often the way things are carried out in the very specifics of how things work come from the bottom. So in this case, what happened was they decided to try this. And what happened is soon as they gave women equal work points was that the women came into the fields and guess how much productivity improved?

It tripled.

Tripled, wow. There you go. There you go.

So Mao heard about this and he was like, “Right, equal pay for equal work. Women hold up half the sky.” So it really was about the economics. It was also hugely inspirational. And throughout the fifties, China needed all the labor it had. Mao needed everybody pitching in to accomplish what he wanted to accomplish, and that included the men and the women. And there was a very puritanical sense of, people should put off marriage and dedicate themselves to the revolution — Cultural Revolution, all of that ramped up hugely. And of course, people were having sex. People are people.

It’s humanity. Yeah.

So was feminist theory shelved for the Cultural Revolution — you know, that we’re all one great proletariat, no gender exists? How did gender matter in the Cultural Revolution? Or was it not supposed to?

It wasn’t really supposed to. It wasn’t really supposed to. It was the important thing was that everybody get out there and fight and everybody get out there and struggle and do the things that needed to be done, whether it was killing class enemies or making steel.

Diving into the Cultural Revolution here, many people are familiar with masses of Red Guards waving little red books, smashing the Four Olds, killing their teachers, marching for Mao — but I think fewer are aware that the Cultural Revolution, in a very real sense, for maybe the last seven, eight years of it with a highlight maybe in between ‘67 and ‘69, was a military conflict involving the People’s Liberation Army.

It wasn’t exactly a military conflict, but it was a militarized conflict. So what happened was, in 1967 to many generals, just many older veterans were really upset at this. They just, they said, this should not be the case. Mao and Lin Biao involved the army in factional conflicts. At the time there were various people fighting to take control of local governments, to set up what they call three-way committees or that kind of came out of this.

But what was going on was that there was actual fighting between Red Guard groups or Red Guard and other radical groups, and Mao ordered and Lin Biao ordered the army in to take the side of the true radicals, of the most left — which meant the army in each place had to make a judgment call on that. And the older veterans were very unhappy about this because they said the Army shouldn’t be politicized like that.

Yeah, I know that Andrew Walter has done research showing that the conflict in Guangxi was especially violent because of all the arms getting sent to Vietnam, which of course the Vietnam War was going on at the time, and that radicals were commandering artillery, anti-aircraft weapons.

Oh, yeah. I quote him actually.

So who was Lin Biao? He was Mao’s former number two, and his death in 1971 kind of marked the halfway point, but also the highwater point in some ways of the Cultural Revolution. And what do you make of his character?

There’s a lot of diverging opinions. Some people have him as basically a psychologically shattered, hydrophobic guy who is basically manipulated by his wife and his son. And then I think in your book, you actually put forward a much different thing: that Lin Biao’s genius theory — where he posited that he wanted to make sure that Mao’s genius was enshrined in the Constitution — was maybe a way to cultivate his own place as Mao’s successor and Lin Liguo, his son’s place as the “super genius” successor.

So in your estimation, who was Lin Biao?

All of the above.

We have to remember how he came up. It was interesting like Kang Sheng, he proved himself to Mao through loyalty. So Kang Sheng, Mao’s head of secret police, had actually studied under Stalin’s very notorious head of the secret police. He was, and again, Kang Sheng was a major character. He was very contradictory. He was vicious. He was sadistic, brutal, completely loyal to Mao. And he was also an aesthete who knew his porcelains.

You write about cultural preservation that Kang Sheng ended up skimming off the finest preserved pieces that the Red Guards needed to struggle against.

Exactly. But Lin Biao, too; It’s what makes people interesting is that they’re so contradictory. In 1958, the Great Leap Forward had started. It was already clear that this forced hyper-collectivization of agriculture and industry and trying to plant crops that were four times as dense as really can be planted.

It was clear that crops were failing and that there was gonna be a real problem with starvation if the course wasn’t corrected. So the Minister of Defense at the time Peng Dehuai, he wrote a letter to Mao and presented it to him. The leaders were at a conference on Lushan.

Mao was furious, and he said that if other people supported Peng Dehuai, he would raise a new army, a new red army, and overthrow the government. And of course, Peng Dehuai gets purged. He brings in Lin Biao of whose loyalty he was assured. And Lin Biao for the first part of the sixties leading up to the Cultural Revolution, worked really hard on Mao’s personality cult.

In having the People’s Liberation Daily publish quotations from Chairman Mao. Lin Biao compiled the little red book. It was plastic cover, distinctive look. It was small because it was intended for soldiers to be able to carry it everywhere. And so by the time we have the Cultural Revolution starting, he’s by Mao’s side. Mao trusts him.

When Mao realized he shouldn’t trust him, that marks a turning point, not just because Lin Biao, this very big figure in the whole thing, gets purged, but because the people began to say, “How can Mao be so wrong about somebody?” Because it came out, Lin Biao was trying to assassinate Mao. It was this whole plot, and then he escapes. He’s trying to escape to the Soviet Union, and his whole family dies in a plane crash over Mongolia. How did Mao get that so wrong? That was a moment when people’s faith began to waver. It was the crack. It was a huge moment. So yeah, Lin Biao is a complex person.

We don’t know for sure because we just don’t know. And I don’t know that we’ll ever know.

Yeah. Unless the archives in Beijing one day open up but even still, who knows what remains. Speaking of which, the crack. That wavering faith is also another, it’s an undercurrent, I’d say throughout the book of humanism in the Cultural Revolution. You write that kind of perversely, the chaos of the Cultural Revolution afforded some people the liberty to explore their intellectual passions in secret.

You have an anecdote about studying oracle bones while Red Guard peers roamed the country. And then the sharing of samizdat poetry and novels, poetry specifically, because it was easy to memorize and copy and share. And I think, there were a lot of turbulent creative forces that spilled out near the end of the Cultural Revolution in things like the Li-Yi-Zhe dazibao (大字报, big character poster)and the swing dancing under red banners that so vexed Jiang Qing.

I don’t think it was actual swing dancing but she was like, “Oh my god, people today they’re just doing this crazy stuff. And it wasn’t that crazy. It was really straight. And she was like, “They might as well be swing dancing naked.”

So that’s my question. This mass brainwashing of a society is a term that I disagree with as you can’t really brainwash people. How did the Cultural Revolution create a different intellectual tack for China or unleash old forces, maybe, because a lot of this was studied in ancient things?

By the time the Cultural Revolution started, we have a whole new generation of young people who have grown up under socialism. And these young people never knew a non-communist China and their whole education they had been around the heroic Communist Party under Mao fighting the Japanese, winning the Civil War against the evil corrupt Chiang Kai-shek and saving the country. So they then were presented with this notion that Mao was under attack. “Bombard the headquarters,” the title of my book, that’s what he wrote when he felt he was being under attack by the President Liu Shaoqi, by Deng Xiaoping and by others.

And he called on his followers to bombard the headquarters. They, the first Red Guards — He didn’t form the Red Guards. They formed themselves. They were something he hadn’t envisioned, but once they existed, they could obviously be put to good use — but they were passionate. These are young people who came to Yuanmingyuan, the old summer palace that had been burned down in the Opium Wars, and they vowed to protect Mao with their lives. They called themselves Red Guards for that reason. They were guardians of the red, guardians of Mao. And that sense of danger, of crisis and of answering the call to support their hero energized young people. And I have some quotations from various people who talk about being in those rallies that Mao held with Red Guards on Tiananmen Square.

I think there were like eight rallies in all between August and November, 1966. And these eyewitnesses are talking about, nearly fainting with excitement, with just tears coming to their eyes. One describing how Mao comes towards them. And it’s just extraordinary. They cannot believe they’re seeing their hero.

So it was more like a mass hysteria, I think. And of course when that mass hysteria began to die off and the Red Guards had created a lot of problems, and we began to talk about 1967, the Army’s involvement and the Army’s involvement led to, as you said, the entry of military grade weapons into what had previously been street fighting with improvised weapons.

So now they had grenades. Before they would sharpen fence posts. Now they were lobbing grenades and they had automatic weapons and tanks in some cases, and in one case at least warships, which seems pretty amazing. So in some cases they were, the weapons were stolen from the army. In some cases they were given to a particular faction by the army.

And as you said, stolen from the aid that was on its way to the Vietcong. So when the Red Guards, as they began to become disillusioned, as they began to create such havoc that Mao felt they had to put a stop to it. And he sent them all off to the countryside to be reeducated. At this point we shift to a kind of a different thing and it’s the elimination of class enemies. And this is when you get, and this is the one as you said people think of Red Guards struggling their teachers and all of that. We have those pictures in our head. What we don’t have photographs of images in our head of, because we probably don’t have as many photographs, if any, are the murders that were carried out in cold blood.

This is not hysteria. People were sitting down and compiling kill lists. That family doesn’t have any land now, but grandfather was a landlord. We’ll kill them all. We will push the babies off cliffs. We will tie an entire family around sticks of dynamite and blow them up. Something like 72,000 families were wiped out in their entirety. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed this way. And I think it’s important to remember that it was very complex.

The Cultural Revolution was a very complex movement. It had different stages. Once Lin Biao died, to get back to that question, people began to question what they had been doing, question the mass hysteria, question their unquestioning loyalty.

When you’re talking about mass hysteria and things like the elimination of class enemies, it’s the dominant image of students struggling, their teachers and a lot of very personal violence, but the elimination of class enemies was Party-directed. Am I correct in understanding that?

Sort of, it was Party-directed in the sense that there were these campaigns that were announced specifically Cleanse the Class Ranks was the name of one campaign. So again, they put that down from the top. But can you imagine in a village where, I don’t know, somebody’s son has slept with somebody’s daughter and somebody has, whatever.

There’s tons and tons of personal grudges that get fed into a campaign like this as well.

I think one of the things your book does so wonderfully, it sounds odd to say wonderfully, but really details like the Cultural Revolution was this truly brutal decade of state-sanctioned murder, essentially.

Let’s transition a little bit because there’s a popular analogy right now in the United States made by scholars like Geremie Barmé, who we’ve discussed earlier and who also lived through the Cultural Revolution himself, and Orville Schell, the publisher of China Books Review, that have compared Donald Trump’s MAGA movement to the Cultural Revolution. In 2017, Barmé wrote of the similarities between Mao and Trump who both have these spirits. “The clash between the tiger like brio and the dyspathy of the monkey,” is what Barmé wrote.

That was about Mao.

That was about Mao, but then also saying that Trump has some of these same ideas and then analyzed, Mao’s quotations versus Trump’s tweets, climate change versus human will — I thought very fascinating — and also Gangs of Four. More recently, Orville Schell compared Elon Musk to Kuai Dafu, the Tsinghua rebel leader who laid siege to the leadership compound Zhongnanhai, among other infamies. What do you make of that analogy?

I’m actually about to give a talk at the Royal Asiatic Society in London on the subject, “Bombard the Headquarters from Mao to Musk,” So I’m clearly in that camp. I think that there’s a lot to be made of that, but it shouldn’t be just simple whateverism. There also has to be discussion of the differences.

The most obvious difference is Mao genuinely believed in communism and he genuinely believed that the people’s will could be used to leapfrog the traditional Marxist map of how you get to communism, that you can actually leap those stages.

And like Trump complete, you know, megalomaniac and would keep people around him completely off guard. You were always nervous. Were you gonna be the next one to be kicked out of the circle? There were a lot of similarities in leadership style.

Elon Musk as Kuai Dafu… I had read Orville’s as well and I quote him in my thing, but not on that one because I think Musk is Kuai Dafu, there’s a better example than the one that Orville gave — he gave a good one, about charging the headquarters and demanding that they turn over various leaders. My favorite Kuai Dafu anecdote, which I write about my book, is he was told to head up a movement to prevent counter-revolutionaries from within the military of staging a coup. Kuai Dafu then, like a little general in a propaganda movie, pours over military maps and he activates people all across the country. They raid various military leaders’ homes. They get a whole bunch of secret documents and they send them all over the country before the top Party leaders go, “Ooh.”

And they couldn’t stop him in time. And that really reminded me of Elon Musk and what DOGE has been doing in the States.

But it’s not just Western commentators who’ve been noticing that thing. Most interesting is many Chinese commentators have been talking about this and their insights are extremely interesting as well, but they’ve been making a similar point. And I think that’s important, that it’s not just outsiders saying, “Oh, look at Trump. He’s like the Cultural Revolution.” It’s actually Chinese thinkers also saying that.

But so when you’re making the comparison between Trump and the Cultural Revolution, you’re describing in terms of leadership style, in terms of a war from within against the party and the state that he feels is shackling him. I don’t think there’s so much of the popular surge in Trump. I don’t see little kids in U.S. military uniform like with printed out tweets in their hands.

No, but there’s a very interesting article that was printed in ChinaFile by a woman who is an immigrant from China. And she and her date, another immigrant from China, and they would consider themselves liberal, pro-democratic process and all this stuff. But they went to a Trump rally out of curiosity shortly before the election. And she said that watching people scream out, “Lock her up, hey,” all this stuff against Kamala Harris, that it reminded her of her mother’s stories of how her grandfather, who was a village Party chief actually once shook Mao’s hand, how he was hounded to death. So she saw the hysteria, the leader worship, the shouting of violent slogans. Very much as part of that. Also, I would say in addition to leadership style, is a complete lack of empathy and an ability to other people so that you can say those people’s lives don’t matter.

Mao was completely fine with violence. Every so often he tried to put a stop to it, but he definitely encouraged it. In the very beginning of the Cultural Revolution, there was a lot of debate within Red Guard circles, should we be violent? Is this right? Should we be beating teachers or just trying to reeducate them? And what happened was the violence went out partly because Mao was encouraging it. He said, “Look, if you beat bad people, great. If you beat good people, it’s a mistake. But how do you get to know people if you don’t beat them up?”

What a logic. And then Trump is saying I could shoot somebody in the middle of Manhattan and I’d still wouldn’t lose any votes. Somebody said that the best way to unite people is to give them an enemy and they can take out all their grievance on that enemy. So the people shouting about Kamala Harris probably didn’t know very much about Kamala Harris at all, but they had rough lives. They’ve felt badly done by. They believe that, I’m talking about America, obviously, but they believe that liberal wokeness — the fact that some people like to state their pronouns — somehow hurts them

And all of this, and Trump gives them something to hate and unites them. And Mao also, they’ve been through the famine of three years,

They’ve been through extreme deprivation and hardship.

Yeah, so you give people an enemy and you can do a lot with them.

Do you think it could happen in China again? Many who survived it — I’m thinking here of the great novelist Ba Jin, who you quote — feared so. Famously, Wen Jiabao, warned about it. And Xi Jinping has very mixed feelings, it seems, about the Cultural Revolution, both as something that was terrible for him personally and horrific for his family. But also as you write in the book, he recalls being the only one smiling while he was getting rusticated.

That’s because he was relieved because his family had been through so much. I don’t know. I’d never say never. I’m not a fortune teller.

But today’s generation is much different from the generations then. Today’s generation has seen a lot of lifestyle choice, a lot of disappointment in other ways. But we do have to remember that some of them have become neo-Maoists, that Mao’s works have again become bestsellers.

This doesn’t mean a new Cultural Revolution is gonna break out. But it does mean that there’s a lot of social tensions and class tensions because the thing that Mao was able to rally people around was this idea of destroying the people who exploit you. And if you’re a delivery worker in China, you’d probably be the first to sign up,

Yeah. No, absolutely.

But it’s, yeah, it’s a big, it’s a big question, but one of the things that I was thinking about is. I don’t know what’s going to happen in the United States. I don’t think anybody does, and there could be violence. I don’t see the kind of wholesale violence. I hope that won’t happen.

But when people say, as one Chinese commentator I was looking at in particular, was like, “Let’s not get carried away with the comparisons, because let’s not forget millions of people died in the Cultural Revolution and this is not happening in America.”

But what I want to say is how do you count the deaths? People have estimated that maybe 1.4 million people will die in Africa in the next couple of years, sub-Saharan Africa, from AIDS because they’re no longer getting access to the medicines because of the end of USAID. And 500,000 children will die over the next five years. I think that’s what I was reading. Which actually is about the same number of people in a shorter period of time. I don’t think we should just be too glib about the consequences of what Trump is doing because people are dying. It’s just not right in front of Americans.

In front of your eyes. And dying for ideological reasons.

Yeah, because exactly.

Because the leader and his top lieutenant have decided they should die. As you say, the lack of empathy, a complete lack of empathy.

I do have one final question, we say you’re still doing subtitling. For listeners— you subtitled Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine, Zhang Yimou’s was it Hero? And maybe other films?

A couple others. To Live, et cetera.

To Live. And are, you’re still subtitling now. Are you subtitling any upcoming films or films that people should be seeing?

So I’ve, I subtitled two of Chen Kaige’s Korean War, post Lake Changjin.

Oh, post Lake Changjin.

Yeah. So I’ve done that. So I do the propaganda films when they come up. I’ve done many other films. A lot that you might not have heard of. I did a number of years ago now, Operation Red Sea, I think that’s a really clever propaganda film. Some of them are not clever. Some of them are just like bang over the head with a hammer.

I was in the Peace Corps and I lived in Bijie, in Guizhou and I’d take the bus to Guiyang, the provincial capital — there was no high-speed rail though it was installed right as I left — and they’d always play Wolf Warrior II on the bus television. So I’ve seen Wolf Warrior II like 20 times.

Oh my god.

Which was, which is rough. It’s clever propaganda. So do you have a next short history coming up or is there any is there any future great events on your horizon?

I had a meeting with my London publisher yesterday and we’re canvassing a few ideas and so I don’t know what will be my next one, but I am working on, this is like the palate cleanser, I’m working on the shortest history of Madrid.

I hope you get to spend a lot of time in Spain.

I’m headed there after London.

I’m jealous. Thank you so much for joining us. This was a wonderful conversation.

Thank you, Alexander. Really great questions.

That was Linda Jaivin talking about her new book Bombard the Headquarters: the Cultural Revolution in China (2025) part of the great events series of old Street Publishing. Check it out wherever you buy books, it comes out very soon in the United States and is already out in the United Kingdom.

This has been an episode of the China Books Podcast – subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and drop us a rating if you liked it. China Books Review is a project of Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations and The Wire China. I’m Alexander Boyd. Write to me anytime at boyd@chinabooksreview.com.

Alec Ash will return next month talking to Jenna Tang, translator of Fang Si-chi’s First Love Paradise. Thanks for listening. ∎

Alexander Boyd is associate editor of China Books Review. He served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Guizhou, China, from 2018-20, and was a contributor to The China Project, Politico and the ChinaTalk podcast. He was previously senior Editor at China Digital Times.