Editor’s note: We’re delighted to introduce our new column “The China Archive”. In addition to our reviews of new titles, every month or so we’ll be reaching up into the China shelves to dust off an older book (often from the deep archive, sometimes in more recent memory) that we think you should know more about. In this opening salvo, Jeremiah Jenne takes us back to a bygone era of travel writing in the 1930s.

Is it possible for a China book to feel dated and current at the same time? In News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir, first published in 1936 by Jonathan Cape, the British travel writer Peter Fleming (elder brother of Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond) recounts a 1935 journey from Beijing to India. Traveling by train, horseback, caravan and on foot, he describes going “three or four thousand miles by way of North Tibet [Qinghai] and Sinkiang [Xinjiang]. The latter province, which had until recently been rent by civil war … was virtually closed to foreign travellers.”

A foreign correspondent trying to replicate Fleming’s journey in 2023 might encounter similar obstacles. Today, it would be the efforts of the Chinese government to obstruct independent reporting from the region, using considerable surveillance and security resources. In Fleming’s time, the situation was the result of a weak state: Chiang Kai-shek’s government had to rely on proxies — usually local militias — to control China’s far west (part of the swathe of central Asia broadly termed ‘Tartary’ at the time) and recover what little was left of their authority in the wake of the recent Kumul Rebellion.

In the 1930s, the Tibetan Plateau and Xinjiang were wild places, still reeling from the collapse of the Qing Empire in 1912. Access was limited. Banditry was rife. Local satraps controlled most of the province. Economic isolation and the breakdown of social order left communities in desperate poverty. Foreign powers furthered their strategic goals by sending money and weapons to dubious allies. It was a geopolitical hot zone, as unwelcoming to Chinese officialdom as it was to passing Etonian travelers. Fleming’s plan to traverse it then was akin to someone today smashing their iPhone on a rock then setting off on foot from Khartoum to Mogadishu.

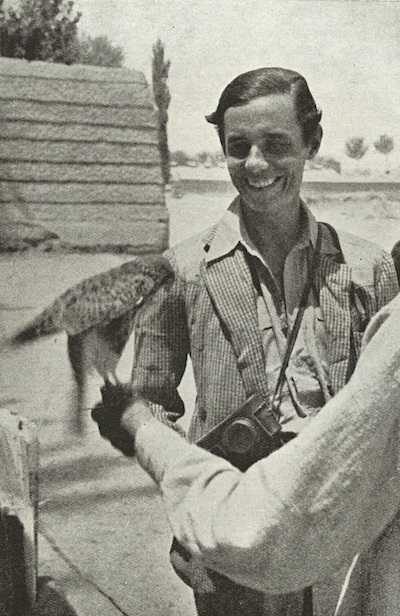

The purpose of the expedition was, in Fleming’s words, to “find out what was happening in Sinkiang … to throw light on a situation whose secrets had since [local uprisings in] 1933 been guarded jealously and with success.” Fleming was, nominally, special correspondent for a newspaper he dubs the “T’ai Wu Shih Pao [泰晤士报], the ‘Newspaper-for-the-Enlightened-Apprehension-of-Scholars’” — which the more prosaically minded might know as The Times of London. Yet rumors abounded that he was also freelancing for British intelligence. A 2008 essay about Fleming and Maillart, by Maureen Mulligan, notes that in the 1980 book Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars, historian Paul Fussell “speculates on the probability that Peter Fleming (brother of Ian Fleming) was involved in undercover work for MI5 during his travels even before his acknowledged work in this area during the Second World War”.

Xinjiang then was a geopolitical hot zone, as unwelcoming to Chinese officialdom as it was to passing Etonian travelers

Fleming was not alone on his journey. Ella “Kini” Maillart, born in Geneva, was an accredited journalist working for the French newspaper Le Petit Parisien, covering the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Maillart had sailed for Switzerland in the 1924 Olympics, captained the Swiss Women’s field hockey team, and was an accomplished mountaineer and skier. She had already written two books, including Turkestan Solo about her trip across Soviet Central Asia, and was a talented photographer and experienced traveler who felt more at home in a lonely tent on the steppe than in a bustling city. Maillart wrote her own account of her trip with Fleming, titled Forbidden Journey, which begs to be read in tandem with News from Tartary.

Both travel companions had something to offer the other. Maillart had experience traveling in Central Asia, a gift for languages, and she was, as Fleming puts it, “good with the natives.” Her presence seems to have eased fears that Fleming might be a threat or a spy, and opened channels of communication to Fleming as a solo male traveler alone. Maillart, meanwhile, valued Fleming for his phlegmatic sense of humor and because she calculated that a British passport might be helpful when they reached India.

She also, somewhat superstitiously, suggested in Forbidden Journey that “Peter was born under a lucky star.” Fleming was inclined to agree. “Every now and then,” he writes in News from Tartary, “you are entitled to expect or to demand, indeed, if only you knew whom to apply, some specific, unmistakable manifestation of good fortune, no matter on how small a scale.” A better working definition of White Male Privilege has yet to appear in print.

Fleming’s respect for Maillart is evident, in part because of his growing awareness that she is better prepared and equipped to handle the rigors of life on the road. Fleming, by his own account, whinges often and views their journey as something to be completed in the shortest amount of days, preferably in time for the start of the hunting season back in Scotland. Each day for Fleming is one day closer to a proper breakfast and the latest copy of The Times.

Despite sharing intimate quarters in tents, inns and huts for many months, there is no evidence that the two had any relationship other than of travel companions. “By all the conventions of desert island fiction, we should have fallen madly in love with each other,” Fleming wrote. “By all the laws of human nature, we should have driven each other crazy with irritation. As it was, we missed these almost equally embarrassing alternatives by a wide margin.” Fleming was engaged to the British actress Celia Johnson at the time, and married her on his return.

Fleming often brags about his ability to travel light, unencumbered by excess physical baggage. I leave it to readers to judge whether such pride is warranted:

Apart from old clothes, a few books, two compasses and two portable typewriters, we took with us from Peking only the following supplies: 2 lb. of marmalade, 4 tins of cocoa, 6 bottles of brandy, 1 bottle of Worcester sauce, 1 lb. of coffee, 3 small packets of chocolate, some soap, and a good deal of tobacco, besides a small store of knives, beads, toys, etc., by way of presents, and a rather scratch assortment of medicines. There may have been a few other oddments which I have forgotten, but these were the chief items.

He neglected to mention the gramophone (though only three records to play on it), which apparently helped amuse locals enough to make the sharing of precious water and shelter a little less awkward.

and Xinjiang, then known as ‘Tartary’

(Michael Wood/CC)

To carry their luggage, Fleming and Maillart shared their journey with a colorful cast of characters. Across the Tibetan Plateau and along the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert, they latched onto caravans heading west, hired camel drivers and porters, bargained for horses, and relied on the kindness of strangers with whom they could barely communicate. It is because of this assistance, for which Fleming occasionally shows a shocking lack of gratitude, that Maillart and he are ultimately able to make it to India despite lacking the necessary documents and passports — such details still mattered even in remote Central Asia — and traveling through some of the most remote and inhospitable territories in the world.

Each day for Fleming is one day closer to a proper breakfast and the latest copy of The Times

And what of the news from Tartary? One wonders if The Times (or British intelligence) ever felt they got a return on their investment for Fleming’s travel expenses. There is a four-chapter interlude in the middle of the book where Fleming gives a potted history of Xinjiang, and he repeats various rumors and speculations regarding nefarious activities in the region, from Japanese encroachment into Mongolia to Soviet influence operations. His main thesis statement, left unproven in any meaningful sense: the Russians seem like they are up to something.

In fact, Fleming wears his lack of contextual information like a holy talisman:

Our ignorance, our chronic lack of advance information, must be unexampled in the annals of modern travel. We had neither of us, before starting, read one in twenty of the books that we ought to have read, and our preconceptions of what a place was going to be like were never based, as they usefully could have been, on the experience of our few but illustrious predecessors in these regions … It was pleasant, in a way, to be journeying always into the blue.

Whether the armchair trekker accompanying Fleming on his expedition finds this refreshing or maddening will vary. One suspects his editors wished for a bit more from their correspondent after four months in the field.

Apart from — or perhaps because of — his quirks, Fleming is a rather charming and rakish travel companion. Modern readers may need to overlook some of his assessments and descriptions (including various “eye-slits” and a “hook-nosed … Moslem”), which, while by no means the worst offenders in the canon of 1930s British travel writing, reflect outdated and, at times, offensive attitudes about his fellow humans.

Nevertheless, his descriptions of Xinjiang as enmeshed in the Great Game politics of rival powers remain eerily current. Like much of Central Asia, narratives about Xinjiang, then and now, focus on the push and pull of established geopolitical actors. Russia. China. The West. India. The region has long been — and may long be fated to be — a geographic cipher, where descriptions reflect the ideological leanings and political interests of outside observers rather than the lived reality of its inhabitants. This also makes the area sensitive for any state attempting to exercise authority there, and it is why such states tend to jealously guard against interlopers. Many of the places that Fleming describes are still off limits for foreigners, especially journalists, in China.

This is a shame. Fleming’s route through the western plateau of Qinghai down to the southern oasis cities of Xinjiang, then up into the high mountain passes separating China and South Asia, are among the most beautiful in the world. Even today, his writing — taking us through such farflung locales as Dzunchia (Golmud), Tsaidam (Qaidam), Issik Pakte, Cherchen (Qiemo), Keriya, Karghalik, Tashkurgan and Nagarkhas — still whisk us out of our armchairs and into the swirling desert sands, or lift our heads into the thin air of the Himalayas. Despite his occasional creaky colonial attitudes and white-boy-in-Asia entitlement, Fleming makes us want to put down our books, pack a bag, and join him on the road. That, after all, is what travel writing is for. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian based in Beijing since 2002. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and has taught Late Imperial and Modern Chinese History for over 16 years. He is co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.