Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Fuchsia Dunlop has been cooking and writing about Chinese food since the early 1990s, when she became the first Westerner to train at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Higher Cuisine. She has written several books, most recently Invitation to a Banquet — a historical celebration of the intricate processes and stunning diversity of the nation’s cuisine. In this Q&A, ungated here from our sibling site The Wire China, Dunlop tells us about her journey with Chinese food, its flavor and sensuality, and what it can teach us about sustainability.

You’ve been a longtime advocate of Chinese cuisine. Why do you think Chinese food though has tended to be looked down upon outside of the country?

It’s mainly for historical reasons. Chinese food in the U.S. and the West in general was largely created by Cantonese immigrants, who were trying to make a living in often hostile circumstances. They came up with a formula of accessible, inexpensive food that appealed to Westerners’ palates — boneless meat, no shells, no fiddly, high grapple-factor foods, and appealing flavors — and it was wildly successful.

To a certain extent, perceptions of Chinese food got stuck: the sweet and sour sauces, the deep fried foods, the fried rice and fried noodles, completely missing out on the food that Chinese people actually eat, which traditionally — and for many people still at home — includes a lot of fresh vegetables, light soups, and steamed as well as fried dishes.

To add to that, China had a very turbulent time during the twentieth century, it was closed to the outside world and ended up being seen as a poor country. Chinese cuisine was not seen as prestigious. By contrast, Japan got rich first, and in turn, Japanese food has become elitist and expensive, with people willing to shell out vast sums of money on things like sushi. Chinese food has got stuck in the “everyone’s favorite neighborhood takeaway restaurant” bracket, and not really seen as being very sophisticated, or worth spending money on.

In part, that was the starting point of my book: to look at some of the Western misconceptions of Chinese food, and in particular, the idea that Chinese food is unhealthy, which is still prevalent. There is, in fact, no other culture that is as obsessed with the connection between diet and health as the Chinese, and this has been the case for 2,000 years. The earliest written recipes in China were medical prescriptions found in some Han dynasty tombs. As anyone who has lived in China knows, Chinese people, particularly the older generation, talk all the time about food as medicine, and what to eat for particular ailments. They say food and medicine come from the same source.

Beyond that, the everyday traditional Chinese diet is a model for healthy eating, with lots of vegetables and grains, and very little meat, some fish. It seems to me that it would offer many of the benefits of the much touted Mediterranean diet.

The other stereotype that I find fascinating is the idea that the Chinese eat everything. To an extent it’s true: The Chinese are particularly adventurous in their choice of ingredients, and they have very few food taboos. They take great delight in texture, and in the intricate mouth-feel of fiddly things like ducks’ tongues and chicken’s feet. All this greatly expands the possibilities of ingredients, as does China’s huge size and biodiversity. But Westerners have always seen this omnivorousness in a very negative light.

And that stereotype is one of the reasons you suggest that Chinese cuisine can offer us some solutions on coping with climate change. Could you expand on that?

Whereas a Western chef will ask about a potential foodstuff “is this edible?”, a Chinese chef is more likely to ask, “how can I make this edible?” Their approach is that, if you use culinary technique and flavorings, you can transform very unlikely ingredients into wonderful delicacies. This is not poverty cooking: this is often very sophisticated, laborious, time-consuming cooking.

One example in the book is pomelo pith, one of my favorite Cantonese dishes. The pith is a particularly uninspiring ingredient. It’s cottony, tasteless, maybe a bit bitter. And yet Cantonese chefs have found a way to soak it to remove the bitterness, and to boil it in a magnificent stock made from chicken and pork and scorched fish, and to serve it in an opulent sauce, with a scattering of shrimp eggs. It becomes something that’s not just acceptable, but utterly delicious. I find this imaginative, and even humorous, approach to cooking very inspiring.

In the 21st century, faced with our global environmental crisis, many cooks and scientists in the West are trying to think of ways of eating more sustainably, of making nice food with seaweed, or with insects, and of mimicking the tastes of meat and fish with plant based foods. The Chinese have been doing this for ages. Anyone who’s looking to find these sorts of dietary solutions should really be looking to China for inspiration, because they’ve been way ahead.

Perceptions of Chinese food have been sullied by all the opprobrium attached to the consumption of shark’s fin and other questionable ingredients. China has the ignominious distinction of being a center of trafficked wildlife for human consumption. But this is a very tiny part of Chinese cuisine. The vast majority of Chinese people have neither the money nor the inclination to eat stuff like that. And there’s a certain amount of Western hypocrisy in discussions about this. The Chinese attract more criticism for eating shark’s fins, than the Japanese do for eating bluefin tuna or Western chefs do for cooking eels, all of which are critically endangered.

This is definitely a part of Chinese gastronomy that needs rethinking. But it has to be a global discussion, in which we recognise that we’re all at fault. The Chinese people who eat shark’s fins would be more receptive to a balanced discussion about this, rather than just western finger pointing.

The art of cooking very early on, 2000 years or more ago, was used as a metaphor for the art of government. It was seen as something very delicate and subtle and skilled.

One of your other big themes is the sheer variety of Chinese cooking. Do we need to start thinking about this continent-sized country more in terms of different regional cuisines? What are the unifying characteristics of Chinese food?

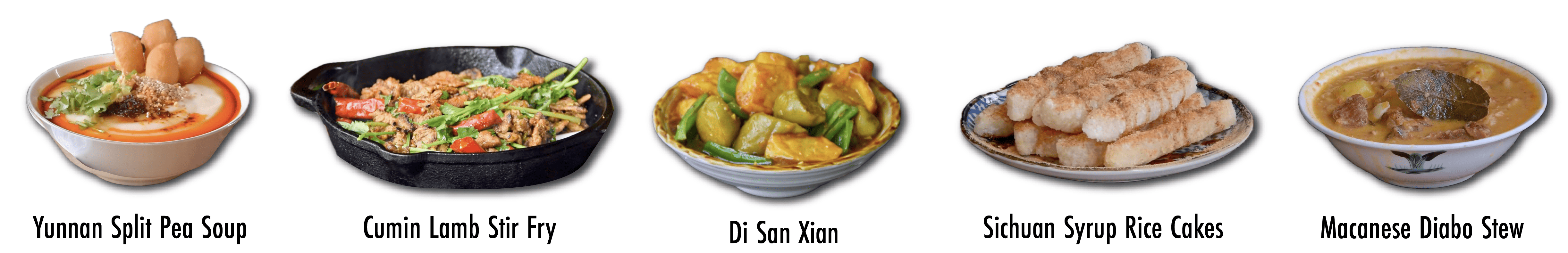

I think it’s helpful both to generalize about Chinese cuisine, and to recognise that this is a vast continent of a country, with many different regional traditions. If you fly from, say, Shanxi in the north, up by the Great Wall, to Xishuangbanna in southern Yunnan, you’re just in another world gastronomically speaking. In the north you have oats and millets, wheat and pasta, lamb and goat meat; in the south, you’re in tropical rainforest territory, with people eating an astonishing range of food, which often has more in common with the culinary traditions of Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. The same goes for many other regions of China.

Moreover, Chinese people have the same hang ups about the food from other regions that Europeans used to have: English people used to be snooty about the French for eating snails and frogs’ legs, for example. In China, southerners think the northerners eat nothing but boring old flour and mutton.

But there are unifying characteristics. One of the most important is the use of chopsticks to eat food that is cut into small pieces. If you go into any Chinese restaurant today, you’ll have stir fry dishes where food is cut into slivers, or little cubes or slices. This is a habit that was forming 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty, and has been very consistent ever since. Because obviously, if you use chopsticks to eat, the food has to be cut into small chop-stickable pieces, or it has to be very soft, so you can tear it apart. That’s a real contrast: If you gave a pork chop to an English chef, they might just fry it in a pan and serve it with some potatoes. If you give it to a Chinese chef, they’d cut it into little slivers, marinate it, and stir fry it with a vegetable. It’s a very different aesthetic and way of eating, with no knives at the table in China.

Another extremely important difference is the use of the soybean, and fermented legumes, which were not ever used in Western cooking, except as a modern Asian influence. The Chinese have been fermenting soybeans for more than 2,000 years. Of course, some hundreds of years later, they started eating a lot of tofu.

This had implications for the Chinese not needing as much meat to sustain a large population on limited arable land; it’s much more efficient to eat soybeans than to feed them to cattle, as most of us do now. This has also affected the Chinese landscape, so that you don’t see pasture lands. These are some of the things that make Chinese food Chinese.

How did your interest in China and Chinese food develop?

I loved eating and cooking as a child; I remember telling a teacher when I was 11 that I wanted to be a chef when I grew up. After university, I wanted to do something with food and to travel: China was an accident. I went backpacking there in 1992, and it was just really interesting and surprising. I came back and started learning Mandarin: to cut a long story short, I got a British Council scholarship to go and study in China and was supposed to be doing something very academic.

But the reason I chose Sichuan University in Chengdu was partly because I knew it was a gastronomic center. When I got there, the food was overwhelmingly delicious and different from any Chinese food I’d had before. I managed to persuade local restaurants to let me into their kitchens to study. I was quite well versed in European cooking, but I had no idea about how all these flavors were created.

Then a German friend and I heard about a famous local cooking school. So we cycled over one day, and got them to agree to give us some private classes. After I’d finished at Sichuan University, not having done much of the work I was supposed to do, I went back to the cooking school, and they invited me to join a professional chefs foundation training course. They had never had a foreigner do this before.

Language wise, it was a big challenge, because the classes were taught in Sichuan dialect, and the textbooks had very specialized culinary vocabulary. But it was such fun, I loved it.

China was still a pretty poor country back then. What changes have you seen over the last 30 years as the economy has taken off?

The changes have been completely dramatic. China has always had a very gastronomic culture, but it was suppressed for decades. People then craved meat and other delicious foods. The nineties saw the beginning of a Chinese economic boom and the availability of food in a way that there hadn’t been for some time. Given the gastronomic inclinations of China, people just leapt at it with real gusto. The upside was a really speedy revival and restaurants getting more and more beautiful food, getting more extravagant; the downside was all the waste, people were serving too much food because of this joyfulness after not having had much for a while.

Now, the high end restaurants in China are unbelievably sophisticated, both in terms of ingredients, culinary technique, the beautiful environment and service. At the same time, I think there’s been a loss of domestic cooking skills, which is really sad. When I was a student there, many of the adults were really competent or even excellent cooks. They could make everything from scratch, they could cure their own winter meats, they made their own pickles. I think this is something that is being lost, because there’s great pressure on young people to study.

Yes, you write about how over the course of Chinese history, there’s been almost a tension between “luxury and simplicity, gluttony and restraint.”

You still have these age old tensions. Some middle class people in the cities are even becoming vegetarian; some are trying to eat more coarse grains, not just white rice, for their health. There’s a big government campaign at the moment against food waste: Practically every restaurant you go into, there’s a graphic encouraging you not to order too much food and waste it. I think that the excessive eating of the 90s is coming to be seen as a bit vulgar.

One person who crops up quite a lot through the book is Dai Jianjun, or A Dai, and his restaurant, the Dragon Well Manor in Zhejiang province. Why has he been so important to you?

One of the reasons that Chinese food has not really been esteemed abroad is that people don’t associate it with quality ingredients. This is completely mad, because the Chinese — at least those who can afford it — have historically been obsessed with the idea of what we would call in European cultures “terroir,” the provenance of ingredients.

When I first went to Dai Jianjun’s restaurant in Hangzhou in 2008, I had a kind of epiphany. Hangzhou is right in the heart of the Jiangnan region, which has been a center of Chinese wealth and sophistication for about 800 years, and a center of Chinese gastronomy and food writing. At the first lunch that I had at his restaurant in 2008, I was eating these wonderful renditions of classic local dishes, made with ingredients that we would think of as organic ingredients. They were making their own tofu in the garden, everything was fresh and seasonal. And I remember thinking that this is the Chinese food that the great gourmets of the 18th century, the food writers, were actually eating in this region, made with wonderful ingredients.

Dai wanted to serve ingredients that his customers could trust. He buys directly from a vast network of producers, farmers and artisans across Zhejiang province and beyond. So he’s both offering a market to people in the countryside to sell their traditional produce as premium produce to middle class consumers, and also encouraging the preservation of agricultural skills giving jobs to people in the countryside. So it’s a big social project as well, and I found that so inspiring.

What explains the ingenuity that Chinese people over the centuries seem to have had towards food and cooking?

Food has been seen as central to Chinese culture since the beginnings of civilization. The core rituals of the ancient Chinese state were offering food and drink to the ancestors and to the gods. The Chinese saw themselves as people who ate cooked food; the barbarians outside China, the uncouth people, were the ones who had raw food.

The art of cooking very early on, 2000 years or more ago, was used as a metaphor for the art of government. It was seen as something very delicate and subtle and skilled. There’s also the argument that because there were famines, and the threat of not having enough food was very present, people really treasured their food. And also that in China — in the past, as now — there was this great bureaucracy in which individuals could be frustrated and cast out. People found solace in food, and cooking was something that you could be very technical and philosophical about.

There are so many different Chinese cooking techniques that they have developed over the centuries. If you have a whole battery of techniques at your command and imagination, then you can do a lot with your ingredients.

So a lot of attention has been put towards food, added to which is China’s quite extraordinary biodiversity. You have Siberian forests in the north, tropical rainforests in the south, the Tibetan Plateau, the watery landscape of Jiangnan, the grasslands of the north, and all these different terrains produce different ingredients.

Food has been seen as central to Chinese culture since the beginnings of civilization. The core rituals of the ancient Chinese state were offering food and drink to the ancestors and to the gods

What do you think is special about the way that Chinese people actually consume and enjoy the food that they have?

One of the most impressive things is the potential to combine healthy, balanced eating with extreme pleasure. Chinese food, if it’s eaten properly, is not only incredibly delicious, it also makes you feel good because the rich, luscious, fatty, meaty dishes are always balanced with fresh vegetables and light soups. The way people eat is a real contrast to a formal English dinner party, with multiple sets of cutlery and crockery and all the clashing of metal on china.

In contrast, at a Chinese banquet, all you really need is a pair of chopsticks, a spoon, a bowl and a plate. There’s something so gentle and caressing about chopsticks, the way they’re an extension of your hand, they give a very intimate engagement with the food. There aren’t lots of silly rules about eating like there are in English. So in China, you can make a few noises of appreciation, you can raise something to your mouth, take a bite, put it back in your rice bowl. There’s a sort of ease with the sensuality of eating, which I think is missing from English dining.

And people talk about food all the time, as a great pleasure — not only the flavor and the smell, but the texture, the physical engagement with your food. If you talk to Chinese people about food, they always describe how it feels, as well as how it tastes. There is this delight in slitheriness and crunchiness, and what I think of as textural oxymorons, something that’s soft and slippery, and then a little bit resistant or crisp at the end. And there’s also the “grapple factor” foods, things that are a little intricate, you have to tease apart the bones and the skin and the cartilage. There’s a sort of uninhibited pleasure in the physicality of eating, which is very joyful.

And there’s a sense of the importance of harmony as well?

That’s one of the reasons that cooking was a symbol of politics in the past. There is a recurring image in Chinese ancient literature, that the art of politics is like the art of seasoning a stew. You had lots of different ingredients, and the art of the chef or the ruler was to make sure that all these contrasting elements were in harmony, so that you ended up with something delicious if it was a soup, or society was stable if you’re talking about politics.

This goes back also to the idea of food as medicine: the idea of good food in China is of food as something that is nourishing of life. It’s not just taste. If you go out for a really good French meal, it’s all about the pleasure. You might stuff your face with all kinds of delicious things, but you’re going to feel comatose by the end of it. A really good Chinese meal should be designed to be harmonious, so that the rich dishes are balanced by lighter dishes; dry dishes are balanced by wet dishes; and if you have something dark in color, you’ll also have some things that are light or bright, the food is cut into different shapes. The whole thing is an exercise in conjuring up a fantastic, holistic harmony out of many different contrasting ingredients without any repetition.

Are there enough young people coming through now who are interested in learning some of the cooking techniques that you describe in the book? And within that, are there enough women?

It has been a very male dominated industry. The explanation always given is that it requires huge strength to operate a wok. When I was first in China, people were often cooking over coal fires that were very hot and relentless, and the woks are heavy, it’s physically intense. So it’s seen as something that’s physically demanding, and also probably not very feminine in a social sense. I have met very few high level female wok chefs and they have been really determined on the whole and exceptional women who were prepared to put up with a lot.

As to the next generation, I think it’s really hard to say. I know some exceptional chefs in China who complain that they can’t get serious apprentices, that young people are not willing to ‘eat bitterness’, which means to put in the hard hours. Many of the older chefs had tough, even brutal apprenticeships. They started as teenagers working under master chefs and spent years doing menial tasks. It was physically exhausting, and not much fun. And so it’s not very surprising that people don’t want to do it. I do worry.

When I was at the cooking school, everything we did was from scratch. Now there are more manufactured sauces, there are more halfway products like seasonings that are ready-made, shortcuts available to chefs. Learning the whole skill, from the raw ingredient to the finished dish, is slightly under threat. I do sometimes wonder whether I’ve been very lucky to be present at the heyday of the revival of Chinese gastronomy — and that I’ve seen some things that we won’t go on seeing very often. ∎

Header: Bamboo shoot soup (AI-generated/Midjourney). All photos courtesy of Fuschia Dunlop.

Andrew Peaple is a UK-based editor at The Wire China. Previously, he was a reporter and editor at The Wall Street Journal, including stints in Beijing from 2007 to 2010 and in Hong Kong from 2015 to 2019, where he was Asia editor for the “Heard on the Street” column, and Asia markets editor. Twitter: @andypeaps