May you live in interesting times, goes the apocryphal Chinese adage. The likely origins of the phrase have been traced back to 19th century British statesman Joseph Chamberlain, who in a 1898 speech connected the age’s “interesting times” to “new objects for anxiety.” In 1936, Chamberlain’s son Austen — also a politician, and half-brother of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain — cited “May you live in an interesting age” in a stump speech as a “Chinese curse.” (It is not; the closest idiom is 宁为太平 ,不做乱世人, “Better to live as a dog in a peaceful age than as a human in a chaotic age.”) Recycling it in a 1966 speech, Robert F. Kennedy helped to popularize the maxim, which was also misquoted by the likes of Albert Camus, Arthur C. Clarke and, later, Hillary Clinton. Chiefly applied as a politician’s scalpel to dissect the age they live it, the invented provenance of the “curse” is a classic case of the child’s game of Telephone — appropriately known in England, where the phrase originated, as Chinese Whispers.

In 2024, we live in interesting times. The coming year will feature critical elections in Taiwan and the U.S., the continuation of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, and a variety of less tangible inflection points for humanity and the planet we live on. Though U.S.-China relations have seen signs of rapprochement, this is a tempting illusion given the mercurial realities of U.S. politics — where Donald Trump has been likened to America’s Mao — and the challenging realities faced by China, with calls for reunification with Taiwan and coded acknowledgement of economic slowdown in Xi Jinping’s customary new year’s address. As ever, these twists and turns will be studied by the two co-publishers of the China Books Review: Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations and The Wire China — as well as at the Review itself.

This year, we are looking forward to several titles which will put China, and its relationship with the world, in the fresh perspective that book-length works can afford. And so, just as we bookended 2023 with a round-up of editor and guest recommendations of books from that year, we see in 2024 with a few upcoming titles to look out for:

Other Rivers

A Chinese Education

Much awaited from the veteran nonfiction writer on China, Peter Hessler’s forthcoming book will be an account of his return to teaching in Sichuan province, two decades after writing River Town. Chronicling the lives of two generations of Chinese students, we expect it to shed light on recent changes in the nation (including the outset of Covid, and new political atmosphere that eventually led to Hessler’s expulsion) through the prism of education.

Soft Burial

A Novel

Novels, and other translated Chinese-language titles, are very much on our radar. This work of fiction, by a popular but controversial Chinese author, promises to be an elliptical take on amnesia and historical trauma, through the unfolding mystery of an ailing protagonist. The book was first praised and later denounced on its publication in Chinese in 2016, and Fang Fang’s previous release in English, Wuhan Diary, was mentioned alongside it in our recent review-essay.

The Mountains Are High

A Year of Escape and Discovery in Rural China

Our team at China Books Review not only covers books on and from China, but occasionally writes them as well. This reported memoir by editor Alec Ash, published next month, relates a year living in a rural village in Dali, southwest China, which has attracted a colorful panoply of escapees from the hustle and bustle of the city — seeking alternative ways of life in the hills, pursuing personal over economic development, and finding ways to feel free in an unfree country.

Other titles are expected this year, but without listed publication dates. Topping that pile for us is Motherland by Jiayang Fan, staff writer at The New Yorker, whose book was acquired by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. We expect it to expand on her New Yorker personal essay about her own migration to America as a child, paralleled by her mother’s story.

As ever, we will run reviews, essays, excerpts and a variety of columns to cover these and more, including Chinese titles and archive picks, on top of our podcast and video book talks at Asia Society. If you haven’t already, sign up for our free, biweekly newsletter to receive all new articles in your inbox, every other Thursday. And follow the site daily on Twitter (X), Facebook and Instagram. (Or indeed pitch us at editor@chinabooksreview.com.)

But featured articles is only a part of the work we do at China Books Review. Behind the curtain, we compile all recent, upcoming and bestselling publications related to China, then present them across four dynamic listings pages. (For publishers or authors keen to see their titles included, please contact us at listings@chinabooksreview.com.) So, if the selections above whet a reader’s appetite, we trust our comprehensive listings will satisfy it:

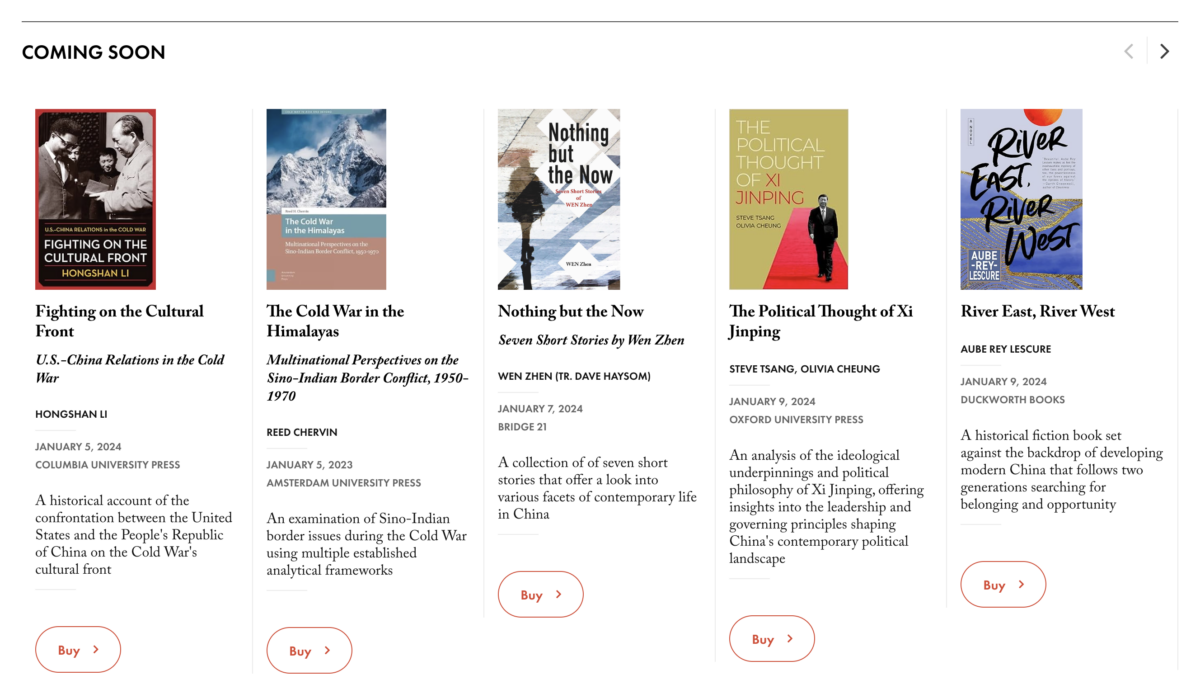

A fuller listing of upcoming China books, defined broadly as any English-language book on or from China that is slated to be published in the next four months. Scrollable carousels are capped at 25 titles across five loose categories: coming soon (combined); politics; history; society/culture; fiction. We update this list every other Thursday.

Upcoming titles, as below and on our homepage, include a mix of genres and publishers as we have found through the listings project — with a heavy spattering of academic books, but also translated and historical fiction, reported nonfiction, the occasional photography, art or even children’s book, and more:

For those books that you didn’t get to last year, there is also our (much longer) listing of recent China books, defined broadly as any English-language book on or from China that was published in the last year. Scrollable carousels are capped at 25 titles across the same five categories, and the list is also updated every other Thursday.

The most recent titles, as below, cover a spectrum of topics as would be expected, but with an especial focus on politics and foreign policy, an ever-present interest in Xi Jinping, but a variety of more specialist subjects in the long tail, such as books on Qing dynasty art and Taiwan’s state-owned air carrier.

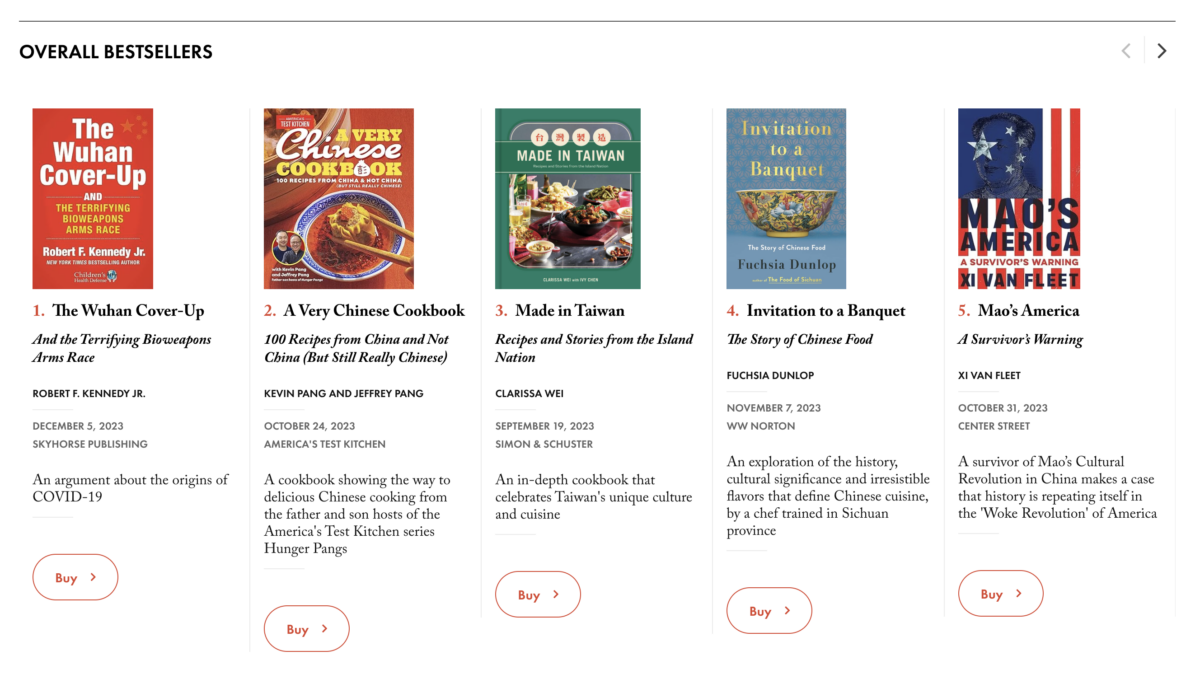

If commercial performance is your standard of interest — or merely piques your interest — then browse our listing of bestselling China books: the same five carousels, but ranked by the books overall bestseller rank on Amazon.com (note this does not incorporate other editions or point-of-sale purchases, so is not a final ranking). We update this list on the first Thursday of every month.

For overall bestsellers, as below, we found an interesting trend emerged for the first three months that we have been tracking the numbers. Namely, the best performing books fell into two categories: cookbooks (three of the top five), and political polemics (the other two, including Robert F. Kennedy Jr and a title anti-recommended by Assistant Editor Taili Ni). We shall see if this holds true.

Finally, a much shorter list — this one selective, not comprehensive — intended to cut through the noise of the high volume of China-related books published each year (300+ by our counting). This listing presents our editors’ picks of new China books, across five categories updated on a quarterly basis: nonfiction (selected by Alec Ash); translated fiction (selected by Jack Hargreaves); Chinese titles (selected by Na Zhong); memoir/biography; and academic books.

The first three categories are taken from our columnists’ quarterly recommendations, with longer blurbs. New nonfiction titles as below, for example, were recommended in an October round-up when this magazine launched:

With these wells to tap, we wish you happy reading in the year ahead — both of China books themselves, and of our reviews and general essays here, which resume from next week. May you live in interesting times. ∎