Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Dali Yang is an American political scientist and sinologist at the University of Chicago, and author of multiple books on China’s political economy. His latest book, Wuhan: How the COVID-19 Outbreak in China Spiraled out of Control, is a deeply researched account of the early days of the pandemic. Yang shows how a combination of factors contributed to the virus’s rapid spread, including failed reporting processes, groupthink among experts, and inherent weaknesses in China’s political system. The work ties in with his earlier research into China’s governance system, which has included books on the post-Mao reform era and the balance between central and local government power. Below, ungated from our sibling site The Wire China, Andrew Peaple asked Yang about the mistakes made by China in Covid’s early days.

Why did you think that now was a good time to research the early days of the pandemic in Wuhan and the causes and origins of COVID-19?

I started following what was happening in Wuhan as soon as it became public in December 2019. I had been in Beijing in 2003 during SARS, doing research on public health-related issues in China. So immediately, I was very intrigued and concerned. Clearly the outbreak became much bigger than it was originally projected to be. I initially thought I’d be writing some articles but the project just kept growing.

Very soon I began to get a sense of mission, that I need to do something about this. There was the feeling that there have been limitations on research related to Covid decision-making in China, and how China handled its response. I have access to a lot of materials and so I felt that I could do something that some of my peers and friends in China might not feel as comfortable doing — and even if they did, they may not be permitted to publish.

COVID-19 is in fact the third novel coronavirus disease in 17 years. Humanity needs to learn that this is truly a gigantic public health event. In fact, Covid hasn’t disappeared and remains a major public health concern. What I contribute could provide information and knowledge, so that we can learn — as you know, the World Health Assembly has been discussing a pandemic accord. China itself has indicated that it wants to undertake certain reforms. Sometimes it’s valuable to have someone who is not as centrally involved in such processes to offer an outsider’s perspective, and provide a more objective look at what happened.

How did you find getting access to the documents and data that you needed?

Those of us who study China often immediately preserve anything that’s interesting, because it may disappear from online sources, social media, and so on. I was doing that as soon as information became available. But because of how big this event was and the tremendous amount of public concern within China from Chinese journalists, media sources, social media, and many others, there was just a humongous amount of information that became available from local, national and international sources. I was able to conduct some interviews and I had various contacts that helped me to grasp what was happening.

Clearly, I would have preferred to have more access. But compared to most events and developments in China, there’s just an overwhelming amount of information to digest and go through. This was an emergency that involved multiple layers of the bureaucracy, and people in many different localities. Part of what I have done is to be able to connect all those different developments and multiple levels across space and time, throughout the hierarchy. And, of course, from laboratories, to hospitals, to CDCs [Centers for Disease Control] to health commissions. All those institutions are embedded in an extremely complex political and administrative environment.

Let’s turn to the beginnings of the pandemic, and the virus that first spread in Wuhan. When you look back to late December 2019, what were the initial missteps in those fateful early days?

China had developed a national disease reporting network, following SARS. It was designed to overcome many of the administrative fissures within the Chinese system, and to enable clinicians and local hospitals to input information about infectious disease cases into the system, so that multiple levels of the government, including the China CDC, could directly see this information from Beijing. That system wasn’t used at all for the initial reporting [of the virus]. That was truly shocking and it underscored and highlighted the challenges within the Chinese system.

Later on, the official discourse became that this virus had emerged out of nowhere, that it was such a big surprise, we were just not prepared; and when it spread, there were arduous efforts made to contain it — and that China was very successful compared to many other countries.

What I tried to do was to tease out what information had been available about the outbreak. What did decision-makers know, and what did they do with the information? I was struck by the amount of information that was actually available at the end of December 2019, in spite of the fact that the disease reporting network was not used around and before that time.

Why did so many within the local authorities in Wuhan fixate on the Huanan seafood market as the source of the virus early on? And why were they so slow to acknowledge that it could be spread from human to human, and that it wasn’t just coming from animals to humans?

This cuts to the central argument of the book. This happened in spite of the enormously good information that the authorities had, and the SARS-like symptoms that patients were displaying — which prompted clinicians to undertake testing and to don protective gear for themselves. At the same time, they had access to multiple genomic sequences from labs around the country, from Wuhan to Guangzhou to Beijing.

From the very beginning clinicians saw SARS-like symptoms emerging. But there was a studious effort by the authorities to avoid any reference to SARS publicly … It was almost like a taboo.

After the initial patients’ cases were reported to the Hubei provincial health commission, the authorities organized a joint investigation team, comprised of experts from Hubei province and the city of Wuhan and staff from the district CDCs. They saw initially that most of the patients were associated with the seafood market. And so they started out with the idea that such an unusual case of pneumonia must be due to exposure to the seafood market. Some of the symptoms looked similar to SARS. And of course, SARS in 2003 was later confirmed to have jumped from animals, especially from civets, in Guangdong. This is the mental map that many of the people involved in 2019 used to view the new cases emerging.

There is a big problem with this. The first cluster of cases was reported by a clinician or doctor named Dr. Zhang Jixian [a doctor working in the Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine], who was officially credited for being the first physician to report the unusual pneumonia cases. She reported seven cases on December 29: the first three of those cases were from a family that had had no exposure to the seafood market. However, when the definition had been set that the cases were people with certain symptoms who had exposure to the seafood market, those other cases — those that lacked the market exposure — were pushed aside.

The experts outside of Wuhan, including those coming in from Beijing, were getting their information from the local experts on the ground. And of course, the information confirmed their priors, essentially, that the virus must have come from some animals from the seafood market, because most of the patients were either from there or had been moving around the market. And so the suspicion of the experts was that even if you hadn’t gone into the market, somehow you would have come into contact with some animal, directly or indirectly.

There was a very interesting and tragic decision made: Some of the leading experts felt that if they didn’t define the virus narrowly in this way, they would end up having to do too many tests on people — because it was flu season anyway, there would be too many suspected cases. There was a sense that we have to narrow this down to avoid bias. But of course, it ended up being a bias of a different kind.

With hindsight it’s so easy: why didn’t they test those people who had had no exposure to the market, but nonetheless had the same symptoms? There were some tests done, in fact, but somehow the connections were not made, in terms of the spread of the virus. That again, goes back to the assumption that the virus came from animal sources — in virological terms, via zoonosis — and that therefore the spread would be relatively limited initially, and therefore, we shouldn’t worry too much.

It played to that human bias that if we define this in a limited way, it will seem more controllable.

That’s what the evidence tells me. But of course, this is where the situation becomes very interesting. The China CDC’s job was to help to identify and assess the outbreak, and its severity. In many ways, China, since SARS, had developed tremendous capabilities in science and testing capabilities. So it’s not that there was no testing capability when the number of cases was relatively small. But the situation required some imagination. The job of the public health leadership should have been to do that kind of testing and to help identify the risks, rather than to say, ‘Oh, that’s too much work.’

This was truly a very sad and tragic development. If the initial theories had been right, after the Huanan seafood market was closed down there should have been no new cases from people with no exposure to the market. However, hospitals in Wuhan continued to see new cases of people with the same symptoms; but of course, they didn’t qualify as suspected cases [of the virus] as they didn’t come under the definition of having exposure to the Huanan market. Some of the clinicians in Wuhan still wanted to submit these cases into the system, and wanted the health commission leaders to know that this outbreak was contagious. Nonetheless, it took such a long time for those cases to be recognized, and to be tested.

One of the key things that emerged in this three to four-week period around the end of December 2019 and early January 2020 is a reluctance for people to funnel bad news up the chain. What explains that, based on your research into what happened in Wuhan?

This is an extremely complex issue, but overall, it falls under the rubric of incentives. Local authorities, for example, don’t like others to know that they have an outbreak that could affect their economy. The Wuhan authorities were particularly eager to boost their economy: they had just held the World Military Games, and the city was looking its best. There was an almost euphoric atmosphere in the fall and early winter of 2019. So why would they want others to know that they had an infectious disease outbreak?

Individual hospitals also don’t like others to know that they may have infected doctors. All of those factors are at play. And of course, it was New Year’s time, the Lunar New Year was coming, and the city was holding its annual political power sessions.

What role did those political meetings that take place in early January play?

This is almost always the time of year when the local media and the national media want bad news to disappear. Instead, they want to have all those great banner headlines, with glowing reports of achievements in the province and in the city. The timing provided a very strong incentive for officials to say, couldn’t we wait, couldn’t we put that away [with regard to reports of the virus]. There doesn’t even need to have been an explicit guideline: It could simply be that everyone understood tacitly that they needed to do something [to keep this quiet].

What struck me is that from the very beginning clinicians saw SARS-like symptoms emerging. But there was a studious effort by the authorities to avoid any reference to SARS publicly from anyone, including the clinicians. It was almost like a taboo, there was this massive effort to stay silent on any reference to SARS. Later on the Chinese government, through its proxies, also tried to avoid the novel coronavirus from being named SARS. Of course, it eventually did get named SARS-CoV-2, over their objections, by an international panel of experts. In contrast, the WHO named the disease as coronavirus disease [Covid].

Is there any case to be made in support of those within the Chinese system back in January 2020 who were saying, let’s keep this under wraps — because they didn’t want to cause unnecessary unrest and panic?

Those kinds of tensions clearly are universal, and we saw them in other countries. But China, almost uniquely, had the experience of SARS, when they were supposed to have learned the lessons of trying to hide a fire by wrapping it up with paper. This is why China developed, for example, its disease reporting network, so that in theory cases would not be hidden. After 2003, the Chinese leadership had made a big public push to boost transparency regarding infectious diseases.

In January 2020, the Chinese leadership did eventually decide to emphasize that they needed to be transparent by the time of the Wuhan lockdown, which was much quicker compared to 2003. Initially, however, there was still a very serious effort to not let the public know and, more importantly, to downplay the risk.

(Princeton University Library)

Is it your contention that if the authorities, in particular in Wuhan and Hubei province, had been more open and transparent about what was happening, that that could have mitigated the spread of Covid?

Absolutely. In particular, because unlike in many other countries, where if you ask people to put on face masks there would be a lot of resistance, China had had the experience and searing memories of SARS. The mere mention that this was a SARS-like virus, so take precautions, would have elicited a much swifter public response, and people would have generally complied.

People say you can’t possibly lock down an entire city of more than 10 million people right away. I would agree. But the point is there would have been the possibility of targeted lockdowns for certain neighborhoods, and so on. Most importantly, there would have been more efforts to prepare people to take different precautionary measures.

Regardless of how the virus got to Wuhan, information about the novel coronavirus was there already in a significant way at the end of December 2019.

What we do know is [some] doctors were willing and wanting to speak up, and Chinese journalists were eager to report on the story. The information would have been available to the public if they had been permitted. If we had such a system in China, one could imagine that it would not have taken until December 30 for the public to have had some indication of the outbreak. In fact, the China CDC leadership and its Director General Gao Fu, learned about the outbreak from social media sources, not from the Wuhan and Hubei authorities. If there had been greater transparency it’s clear he wouldn’t have had to wait until December 30 to find out. And that again, would have helped to advance the timeline in terms of the health authorities being able to undertake certain measures and responses.

You follow many other political scientists in describing China’s system as being one of ‘fragmented authoritarianism’. Can you explain what you mean by and how it became evident through what happened in Wuhan.

This is a very interesting dimension of China. The typical view is that there is one central command in China, with monolithic, top down control. In certain respects power is very centralized. But in fact for many social, economic and health policy domains, authority is actually heavily decentralized and fragmented.

Just to give an example: The China CDC has a national office based in Beijing, which has a relatively small number of people and labs and so on. Meanwhile every province, city and district has its own CDC. And those CDCs report to the health commissions of their respective jurisdictions; they don’t directly report to the China CDC in the center. The overall political and administrative responsibility lies with the local authorities.

So this is why we find a situation where in Wuhan, when the China CDC emergency operations people initially come in, the National Health Commission — which oversees the China CDC — specifically mentions that health issues like this are the responsibility of the Hubei provincial authorities. This became a very public issue on January 19, when the clouds really had gathered, and both sides recognized the situation was becoming much more serious than they had expected: the local authorities made a statement saying that they had done a good job, under the leadership of the National Health Commission. And the National Health Commission said, ‘we have done a good job, but the primary responsibility is with the local authority.’ You can read between the lines: they were really preparing for things to turn sour and to be able to blame others, even though on the surface, they were saying that they had done a good job.

Of course, all this is not entirely unexpected. In any outbreak, there will be some missteps and problems. But there were multiple channels of information that got blocked during the Wuhan outbreak. In fact, there was one major hospital that independently conducted tests in Wuhan [in early January 2020]: it didn’t follow the central regulations, but concluded that there was human-to-human transmission, that the virus was contagious, and tried to report this information to the authorities. So it’s not that there were no courageous doctors and others willing to speak up and sacrifice their jobs.

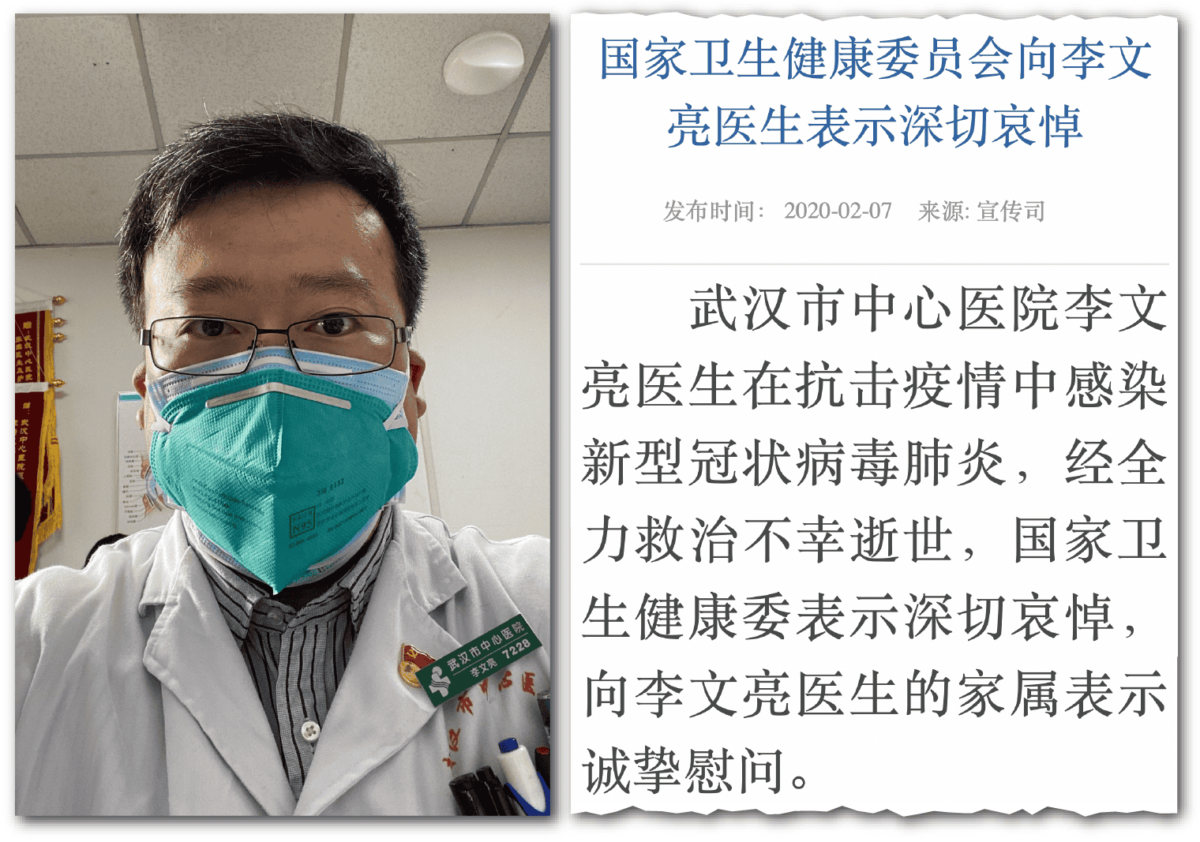

The death of Dr. Li Wenliang is a story that many will remember from the early days of Covid, both within China and internationally. When you look back on that now, how do you analyze the anger that was stirred up by his death inside China?

That was a truly remarkable, poignant moment. I think a lot of the anger on the part of the public started when we were told that there was human-to-human transmission on January 20th. Then came the lockdown. Then, by February 7th [the day Dr Li’s death was announced], the number of cases was still jumping dramatically, especially in Wuhan. The outbreak was nowhere near being contained. At that point, people were isolated and were living in fear, not just in Wuhan, but throughout the country. And at the same time, they had learned that Dr. Li had earlier been reprimanded by the police for sharing information. And they recognized that they could have been told that information much earlier.

They also came to see Dr. Li as a martyr, because he had worked in a hospital [Wuhan Central] where the leadership tried to prevent doctors from wearing face masks. So there was just a tremendous amount of anger at the mistreatment.

How do you assess the role of Xi Jinping and the top leadership played through this period?

The overall political environment within China has made many officials more risk averse. Of course, they still have agency. But they are influenced by a system within which they don’t want to risk their own careers.

As to Xi himself, he wanted the outbreak to be controlled. But he also didn’t want to upset the country’s stability. In the process, the authorities began to control information instead of controlling the outbreak, in a way. Later on Xi expressed his frustration as to why authorities at all levels always needed him to make the decision. Of course, under him the party has introduced documents requiring that local authorities report major cases to the leadership at superior levels for them to provide guidance and make decisions. It’s a very complicated mindset and system.

Because the information [about new suspected cases] was confined initially [within Wuhan], that led the experts at the national level to conclude that the outbreak was limited and under control. So of course, Xi went on his travels, including to Myanmar [during January 2020]. It was after he returned that it became clearer that the situation had gotten out of hand.

Did you come to a particular view about the origins of Covid?

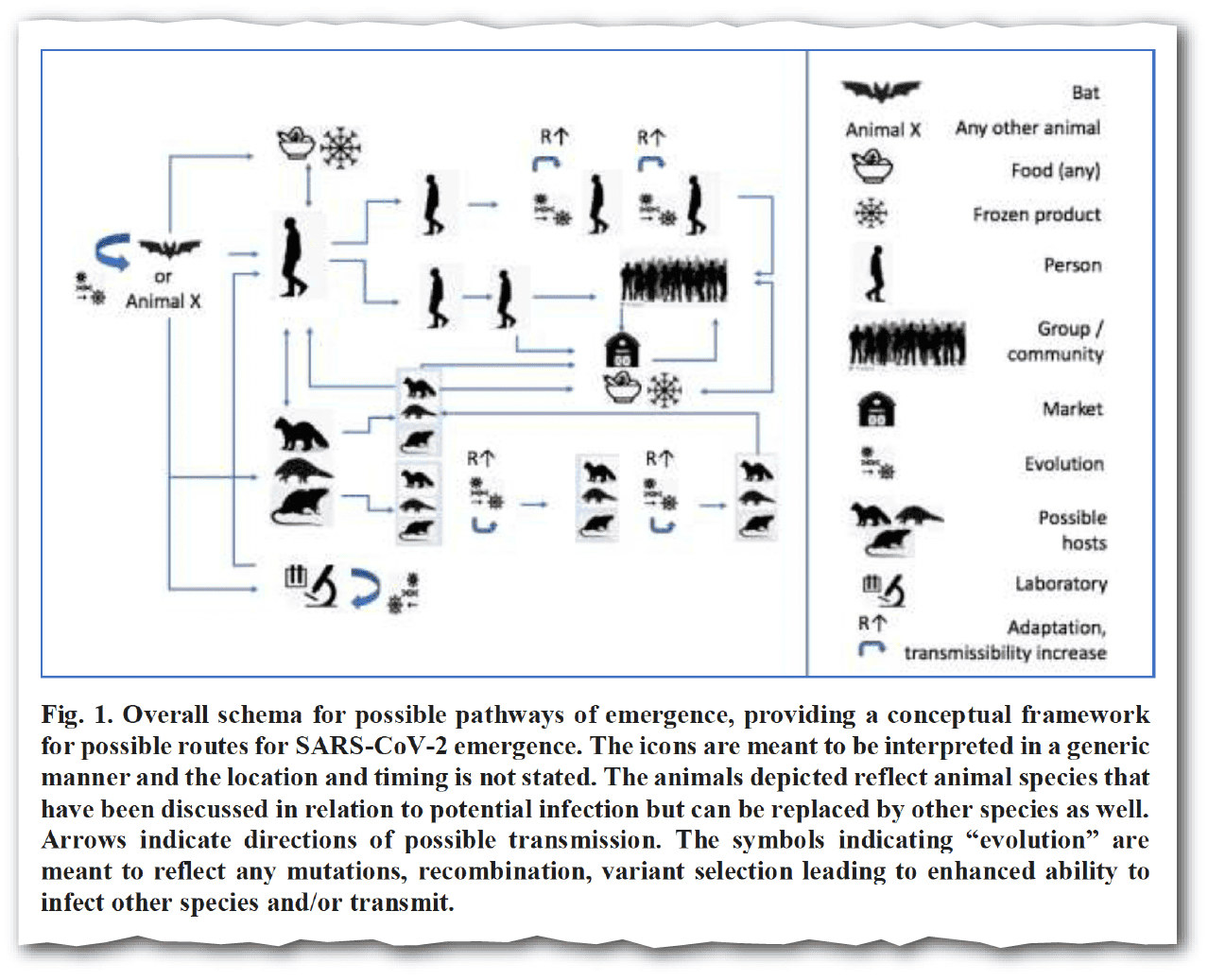

From the very beginning there were two dominant views: the zoonosis theory, which was the operating hypothesis for the Chinese epidemiology community; and also some suspicion that it could have leaked from a lab in Wuhan. In fact, some Chinese scientists raised that possibility initially, and I was very well aware of it from the very beginning. So I have been following the debate very closely.

I’m open because even CDC Director General Gao Fu and his team have really changed their views over time. They are now of the view that it’s possible that the virus did not jump from an animal to a human in the Huanan seafood market; it could have been at a different market, for example. And of course, it could have been imported, because the trafficking of animals is fairly global.

There are other more conspiracy-like arguments about how the virus may have been imported into Wuhan. My argument here, however, is that regardless of how the virus got to Wuhan, got to the Huanan seafood market area where most of the patients were found initially, information about the novel coronavirus was there already in a significant way at the end of December 2019.

What do you see as the lasting legacy of the period that you write about?

In one of my earlier books I looked at the consequences of the Great Leap famine that happened in China in the late 1950s, making the argument that it became one of the most important motivating factors for subsequent reforms that liberated the Chinese rural population from the communist system in the 1980s. Similarly, I think the full scope of the consequences and impact of the outbreak in Wuhan may not be known until long into the future.

The most near-term legacy is that the entire population globally is still threatened by the multiple mutations that have happened of the virus; and therefore the health consequences will be very, very significant over time. We are just beginning to get a sense of the many people who continue to suffer from the adverse effects of the initial infections, and even with various vaccinations, long Covid remains a serious issue.

The problem is that within the country, there are multiple interests that could continue to affect the circulation of information, and the monitoring and surveillance mechanisms.

China has been carrying out some reforms of its infectious disease reporting system, and its overall health emergency response system. Very soon after the outbreak, the National People’s Congress of China issued a decision banning the consumption of illegal wildlife. Institutional reforms have so far been more limited and tentative, because for the last three years or so, the entire system in China has been devoted to the zero-Covid campaign instead of reforms. Some of the leadership have been replaced, including at the China CDC, the China CDC now reports to a national administration of Disease Prevention and Control.

There remain challenges because local government reforms are still to be carried out. And even if they are carried out, the system will continue to be subject to the tensions of what we mentioned and referred to as China’s ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ system. Local authorities will still have some incentives [to suppress information], even if they have been told not to.

In time we will find out what the World Health Assembly decides to adopt in the pandemic accord [with regard to infectious disease reporting]. But typically that deals with reporting at the national level. The problem is that within the country, there are multiple interests that could continue to affect the circulation of information and the monitoring and surveillance mechanisms. The problem is very often there are a lot of political interests involved in this.

China is continuing to invest in more diagnostic capabilities. The problem, though, is not that there wasn’t enough diagnostic capability. The problem was not that there were no professionals who were willing to speak up, [and] that they were shut up [if they did]. So it’s a political issue, and it requires a political solution and alleviation — rather than a technocratic solution, because the technocratic solution that was introduced after SARS in 2003 failed, unfortunately. ∎

Andrew Peaple is a UK-based editor at The Wire China. Previously, he was a reporter and editor at The Wall Street Journal, including stints in Beijing from 2007 to 2010 and in Hong Kong from 2015 to 2019, where he was Asia editor for the “Heard on the Street” column, and Asia markets editor. Twitter: @andypeaps