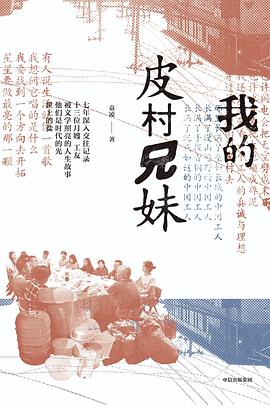

Reviewed: My Brothers and Sisters in Picun, Yuan Ling (CITIC Press Group, May 2024, Chinese edition)《我的皮村兄妹》袁凌 (中信出版集团, 2024)

Yuan Ling (袁凌), one of China’s best-known writers of literary non-fiction, knows too well that creative work often doesn’t pay. Born in 1973 to a rural family in northwestern Shaanxi province’s mountainous Pingli county, a secretarial gig in his hometown court first exposed him to the hopeless circumstances of those left behind by China’s economic miracle in the 1990s. In graduate school in 2003, he joined The Beijing News (新京报), a daring journalistic venture then pushing against the boundaries of state censorship by publishing exposés on SARS, urbanization drives and neglected rural children.

In 2016 he left print for digital media, joining the popular long-form online publisher The Real Story (真实故事计划). But as censors deleted his stories ever more frequently, The Real Story could no longer afford to keep him on payroll. Five years ago, Yuan left journalism in pursuit of his literary dreams, writing acclaimed books such as The Silent Children (寂静的孩子) in 2019, which investigates the dire situation facing left-behind children in China’s countryside, and 2022’s Story of Han River (汉水的故事), tracing the natural history of one of the Yangtze’s most important tributaries.

Yuan’s fifth and latest book, My Brothers and Sisters in Picun (我的皮村兄妹), profiles artists living in a migrant colony on the outskirts of Beijing. By day, they are builders, domestic helpers, assembly-line workers and restaurant waiters. By night, they sing, paint, dance and write poetry. A cast of more than 30 workers populate Yuan’s lyrical reportage; their lives, all the more extraordinary for their transience, give voice to the book’s polyphonic narrative. There is the multihyphenate Lin Qiaozhen, a nanny with a passion for dance who also draws lively pencil sketches and writes ingenuous personal essays about her past in rural Gansu. Fellow domestic worker Shi Yuqin relentlessly documents her life in the face of terminal illness. And poet Xiao Hai drifts between temporary gigs, dreaming of Bob Dylan.

After the book came out in May 2024, Yuan briefly went viral on the Chinese internet for a different reason: he was looking for a job. Fifty-two, car-less, and renting a two-bedroom apartment on the outskirts of Beijing with his wife, Yuan was nearly broke. He had been unable to move his hukou, China’s all-important household registration which determines social benefits, to the capital. The country’s struggling economy had pulled the rug out from under the domestic publishing industry, and sales of My Brothers and Sisters in Picun were disappointing. Yuan wrote on social media in July:

For someone not feeding from the public-sector iron rice bowl, supporting oneself solely through ‘professional’ word-stacking, like I have for the past few years, is now unsustainable, and finding another way to make a living is an urgent necessity.

Yuan’s own precarity undergirds an instinctual understanding of his subjects in this book. Picun (皮村) is an urban village largely inhabited by migrant workers at the eastern edge of Beijing’s vast Chaoyang district. Like other urban villages within China’s megacities, Picun’s infrastructure — from haphazardly built homes occupying legal gray areas to small, cheap eateries — serves former rural farmers who left their ancestral villages in search of better lives. Public policy imagines urban villages as temporary communities stamped for erasure, even though many residents stay for decades. They house delivery drivers, assembly-line workers, caregivers and security guards. Their existences are fundamental to sustaining the country’s industrial and service economies, yet they are just as often destroyed to make space for that same growth. Picun’s one-time landmark was its Culture and Arts Museum of Migrant Laborers (打工文化博物馆), a grassroots institute that sought to make permanent what mainstream society denigrated as an unmoored, transitional kind of life. In My Brothers and Sisters in Picun, Yuan describes the Museum:

The entrance, in big characters, contains a banner which carries that renowned slogan: “Without our culture, we do not have our own history. Without our own history, we do not have a future.” Because it was the afternoon, the museum had few visitors, so I let myself in. The exhibition hall was dimly lit; perhaps the lights were switched off to save on electricity costs. I strolled through the exhibition, looking at each of the famous “artifacts of work”: Wang Dezhi’s certificates of temporary residence, the iron breakfast cart from which Xu Fang once sold stuffed crispy pancakes, and the slippers sewn by Tian Yu, the only survivor of the Foxconn suicides.

Most urban villages stay nameless, patches of apparent chaos in otherwise orderly Chinese cities. But Picun, through its literature, activism and narrative, put itself on the map. The Picun Literary Group (皮村文学小组), founded in 2014, met weekly to discuss reading and writing. The group’s high point came in 2017 when member Fan Yusu’s autobiographical essay, “I Am Fan Yusu,” was published online and became an instant sensation. As media poured into Picun, its artists became the face of a new generation of migrant workers articulating their own public voices.

Most urban villages stay nameless, patches of apparent chaos in otherwise orderly Chinese cities. But Picun put itself on the map.

What does the Picun phenomenon say about a society torn between ever-loftier aspirations of global civilizational leadership and basic inequality at home? Picun’s workers have built, brick by brick, a radical world in which art-making is a fact of life, as essential as air. In rejecting the logic of scarcity, it is a shining, subversive light.

Some of Picun’s writers embrace the title of “New Workers’ Literature” (新工人文学), believing that their genre, though influenced by the older workers’ literature of Marxist-Leninist socialist realism, makes a clean break from its tired frame. No longer were they the idealized, revolutionary proletariat of yore, or the formless revolutionary class of the Maoist era. Their writings reject impositions of collective identity with piercing suspicion. In one poem, Xiao Hai, Picun’s resident romantic, swims upstream against the self:

I once traversed the endless silence, swarming crowds,

I once passed the howling storm, bustling streets

I once found tens of thousands of ways to go on living

I once found the hidden sun

And the solitary moon

But not once have I ever found myself

Each chapter of the book charts the life story of one Picun community member, based on interviews with the workers and Yuan’s own observations. Indeed, the author’s journey into the hearts and minds of Picun constitutes a subplot connecting the chapters together. He is particularly interested in how his subjects become workers and artists: the family circumstances that drove them to the city, the convoluted bus routes they take to get to Picun, the food they buy for sick relatives at home, and their dreams for the future. Yuan avoids overt editorializing, a refreshing choice in an age of spoon-fed “takes.” His plain-spoken tone instead conveys unyielding interest in his subjects’ humanity, subjectivity and citizenship.

Some of the book’s best moments are anecdotes wrapped within linear timelines, which convey the feeling of an intimate interview to the reader. In one of Yuan’s interludes, Wang Haijun, a day laborer in Picun and xiangsheng (traditional Tianjin-style comedy) master, becomes the subject of an “art experiment.” A film director “rents” one square meter of his tiny apartment and forbids him from stepping into that one square meter, in exchange for 3,000 yuan per month — a huge sum for someone subsisting on hourly physical labor. A camera is installed in his apartment to record at all hours, and every time Wang accidentally steps into the square, 50 yuan is deducted from his pay. The recordings become a documentary film on Wang’s life, capturing him eating, sleeping, being questioned by inspectors, even using the bathroom.

Delegated performance art such as this is controversial everywhere, but especially so in China. Yuan’s anecdotes reveal that even Picun, with its cross-class creative collaboration, is not free from the predations of its so-called allies. Of course, one might wonder whether Yuan is himself yet another precarious class actor suckling his artistic ambitions on Picun’s strife, but what at first threatens to compromise his reportage instead works in its favor. Some readers may feel that Yuan’s extensive personal enmeshment with Picun’s artists detracts from impartiality, but his bonds with the community on display throughout the book deflect critiques of exploitation.

More often than not, disadvantaged people are the subjects of art rather than its creators. Picun artists fit uncomfortably into a system of art that presumes leisure and treats quotidian suffering as a spectacle to exploit. In an interview with One Way Street (单读) magazine, Yuan discussed the phenomenon of journalists and academics swarming Picun in its halcyon days of fame, looking for evidence supporting their social theories but ultimately being disappointed. These “passers-by,” according to Yuan, went in search of heroes and villains, but could not tolerate the messy complexity of workers as human beings.

Picun artists fit uncomfortably into a system of art that treats quotidian suffering as a spectacle to exploit.

Yuan moves in and out of each Picun artist’s life, whether as brother in ink, mentor, editor or purveyor of romantic advice. The comradeship that the book’s title gestures at manifests literally, stretching out from days of sorting donated clothes and debating Zhuangzi into nights spent smelling each other’s odorous feet. Yuan commits to the Picun life in form and in spirit, wielding nonfiction as a strategy for imagining the future. The author is keenly aware that the fates of Picun’s writers are a harbinger for the cultural ecosystem of which he is part.

Nostalgia is a common bedfellow of nonfiction, and Yuan often revels in it. In taking pains to portray his connection with Picun as more authentic than those of the passers-by, Yuan perhaps exaggerates his early arrival on the scene. He appears to misrepresent the timeline of his first visit to Picun. Media reports record that he first went in April 2017, the same month “I Am Fan Yusu” went viral, rather than months before as he claims in the book. Professing — and, no doubt, possessing — intimate knowledge of Picun, Yuan writes with an all-knowing voice which, while grounding otherwise disjointed narratives, often lacks self-awareness and fails to acknowledge his limits as a solo journalist. His penchant for imagery anchors an impermanent setting, but can occasionally be an indulgent drag on the quality of his prose, with piles of clothing “rising and falling like mountain ranges.”

My Brothers and Sisters in Picun could be a survival manual for the modern Chinese artist. It recommends organic community, mutual aid and creative amalgamation of resources, all without optimizing for commercial appeal. But it is ultimately a manual that does not believe in its own prescription, because neither its practitioners nor its documentarian are spared from political and economic vicissitudes in the present day.

After the government imposed stringent restrictions on foreign funding for domestic nongovernmental organizations, who Yuan says provided support for Picun, the Migrant Workers’ Home landed in difficult financial straits. In June 2023, the museum was demolished by city authorities. The Tongxin School, which educates migrant children in Picun, will see its lease terminated in 2025. A realist might read My Brothers and Sisters in Picun as not an encomium but an elegy. Yuan seems to mourn not only what Picun once was, but the entire enterprise of literary nonfiction in contemporary China to which he had dedicated his career. He describes the demolition of the museum as the enactment of a dystopia:

The excavators, designed with biomimicry, had teeth resembling those of Godzilla. They ripped apart every roof tile, beam, and reflective glazed surface with force, emitting unbearably deafening, metallic noises. Their iron foreheads barely brushed the walls before toppling them into rubble and twisted steel rebar, discarded at random like strands of pretzels. Massive clouds of dust rose and had to be suppressed by water sprayed from accompanying dust-control vehicles. Nearby apricot trees quivered from the vibrations. The entire scene looked like a slow-motion sequence from an alien invasion movie, yet it was starkly real and brutally swift. The landmark that symbolized “All laborers under the heavens are one family,” along with the countless memories it symbolized, was reduced to ruins in just two hours, as though it had never existed.

Picun, as a way of life, survives. Much of the physical structure is gone, but the literary meetups continue, new members join, and there are spin-offs in other parts of the country. In October 2024, the Tongxin Library opened a new children’s branch. Picun’s writers do not worry about whether they can afford to produce their art, since few other luxuries are affordable, either. Nor do they always write to extend, expand or escape their lives; their work is about looking deeper within. As such, depicted by Yuan’s generous pen, they invite us to consider literature’s potential for resisting all kinds of forced precarity. ∎

Header: The old entrance to Picun village, with the slogan “All workers under heaven are one family” on the left, the sign “to be demolished” on the right. Translations of quotes by Irene Zhang and Alexander Boyd.

Irene Zhang is a Master’s candidate studying Chinese politics at Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies. She is Chinese-Canadian from Vancouver, and was previously a fellow and research scholar at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.