Zhou Liqi (周立齐) grew up without the internet, or much of anything at all. His family was the poorest in a poor village. Their fortunes were tied to their crops, and when the weather brought rains or long, arid stretches, as it did frequently, their crops failed. Zhou was known as Ah San, or Number Three, because he had been born third in a string of brothers. Together, they all lived in a crumbling brick home with a dirt courtyard and a leaking roof in China’s southern Guangxi province. His family could not regularly afford groceries or clothes, and Zhou dropped out of school in the third grade to work.

Most children in his village went to work at the semi-legal brick kilns that dotted the periphery of the village. Zhou knew from his brothers, who had done stints there, that the work digging up clay and retrieving bricks from rudimentary ovens was exhausting and dangerous, and it paid very little. He decided to work construction in the next province over, but he dreamed constantly of living in the cities he was a migrant in, of having his own home instead of building them for other people, and of simple luxuries, like getting to wear clean clothes each day. To fulfill those dreams, he needed to be daring. He ran away to the nearby city of Nanning, where he picked up temp jobs outside the train station. There, he met a girl he intended to marry, whom he called Ah Zhen. But his family could not afford to pay the dowry price her family wanted, and Zhou did not own his own apartment or car, which are usually social prerequisites for marriage in China. That was when he tried for the first time to steal a scooter. He was caught.

The 2012 video of his second attempt and subsequent arrest was shot by a local television station in Guangxi. In the video, Zhou is tanned and unshaven. He is slurring his words. Both his hands are handcuffed to the bars on a police station window, the sweat under his prominent widow’s peak shining under the fluorescent lighting. The local reporter dispatched to interview Zhou asks him why he keeps stealing for a living. Zhou seems baffled by the question: “It is impossible to work part-time; it is impossible to work in this life!” he says. “It is very nice to come to the detention center. It feels like coming home. I love it here.” After the interview concluded, Zhou served a year and a half of prison time, then promptly went back to stealing scooters, sometimes successfully.

The video did not immediately go viral, but in 2016, it suddenly blew up. China, it turns out, has a lot of wannabe slackers. “I had this secret, depraved desire, too,” the journalist Chu Zijing wrote of Zhou’s defiant laziness. Chu, a thoughtful writer in his late twenties when I met him, had tested his way into one of China’s top universities, Tsinghua University, in Beijing. His entire life had been geared toward academic success. However, as an adult, Chu questioned what that hard, repetitive work had been for, and he marveled at Zhou’s honesty and audacity. He saw in the scooter thief ’s laid-back persona a sophisticated approach to rebellion and wrote a nuanced magazine profile of him. “It is not the dissatisfaction of working itself, but rather the dissatisfaction of not being able to have a decent life, despite that work,” he told me over coffee in NPR’s Beijing bureau some years after the video had gone viral. Though he had no formal education, Zhou had intuited that no matter how hard he worked, the real profit from his labor was being captured by other people.

Zhou touched a nerve in Chinese society, which had become more economically unequal even as its economy grew rapidly. The country still suffers from a culture of overtime and underpaid work. I found people in China remarkably ambitious and hard-working, but that also meant stiff competition in the domestic labor market. Add to that a glut of college graduates and a slowing economy and that meant people’s prospects were no longer as bright as they had been before 2020. Internet slang terms like neijuan (内卷) — meaning “involution” — and tangping (躺平)— Chinese for “lying flat” — were peppering everyday vernacular. Tired of working hard but getting nowhere (involution), China’s youth just wanted to lie down and lie flat.

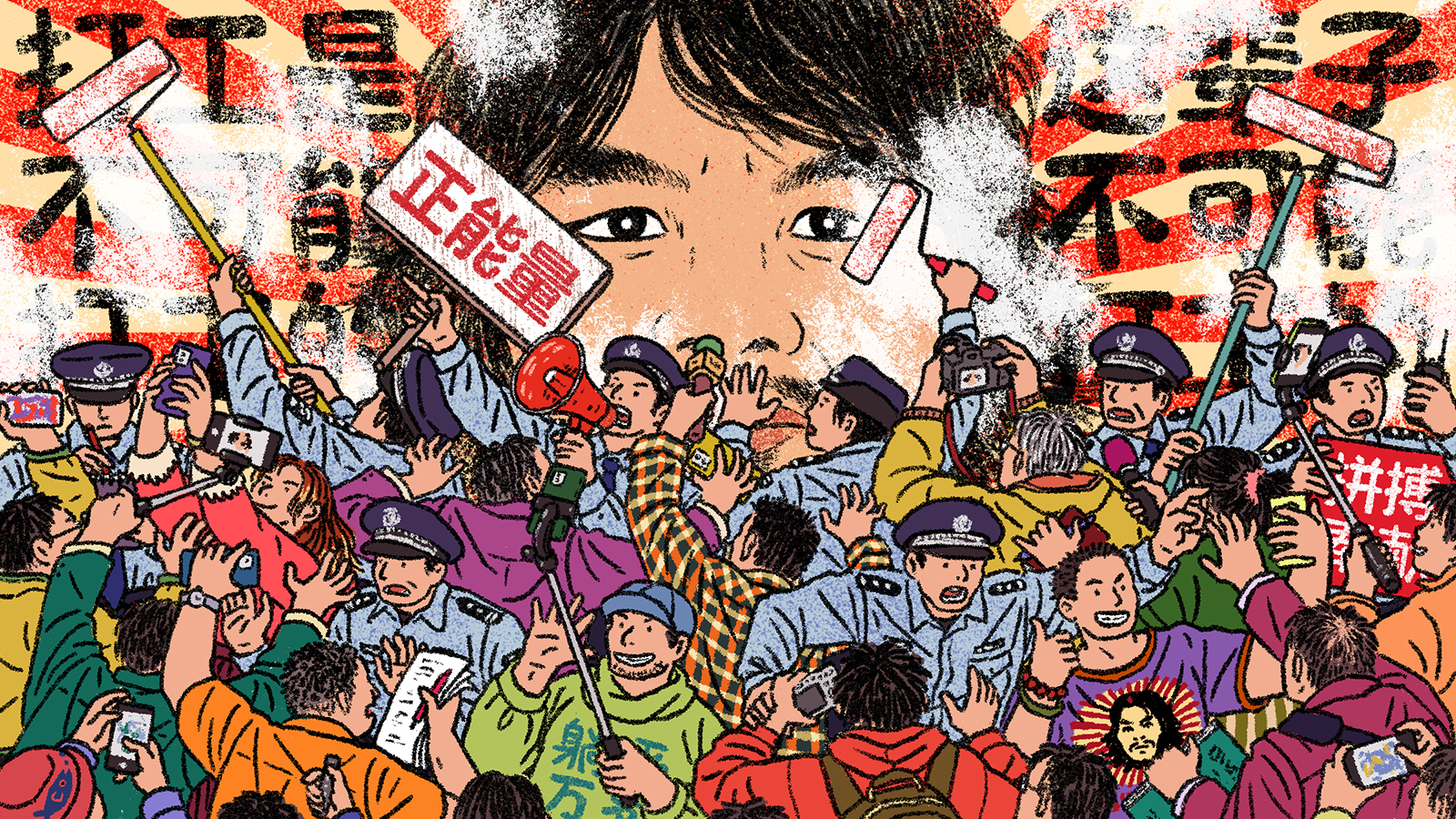

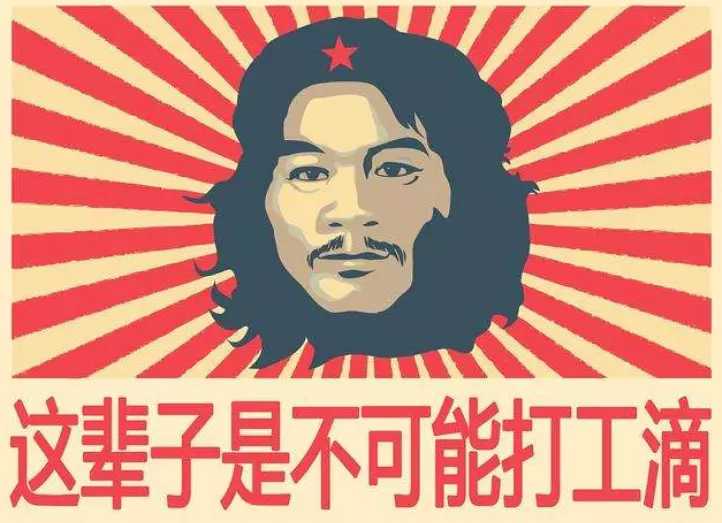

In a country where organized social dissent, both online and offline, can be a criminal offense, Zhou’s rejection of work offered an alternative, more passive mode of protest. Unable to change the institutions in which they worked, people simply withdrew from them. His jailhouse interview inspired an entire internet subculture. One magazine profile designated him “the spiritual leader of slackers.” With his wispy goatee and long black hair, Zhou looked more than a little bit like an Asian Che Guevara, the guerrilla Communist fighter celebrated in Cuba, and memes of Zhou photoshopped to appear in Che’s signature beret proliferated across the Chinese internet. Several large online forums populated by his fans outright encouraged practicing delinquency and time theft on the job. One of these forums, named Quit Gambling, grew to 4 million participants who posted screenshots of themselves goofing off at work. The group also attracted scammers who used Zhou’s trademark “I can’t work” motto to sell online loans and dubious financial products. By one estimate, articles about him in The Paper, a well-known news outlet, had been read at least 160 million times, and videos of him had been watched some 300 million times.

Zhou had intuited that no matter how hard he worked, the real profit from his labor was being captured by other people.

Zhou himself was oblivious to the media storm because he was back in prison. This time he was serving out his fourth prison sentence for, once again, stealing scooters. He had never seen a short video or heard of TikTok before, but suddenly, on the outside, he was a video star. His brothers were forced to slaughter all their chickens and ducks to feed the well-wishers who began coming to their family home.

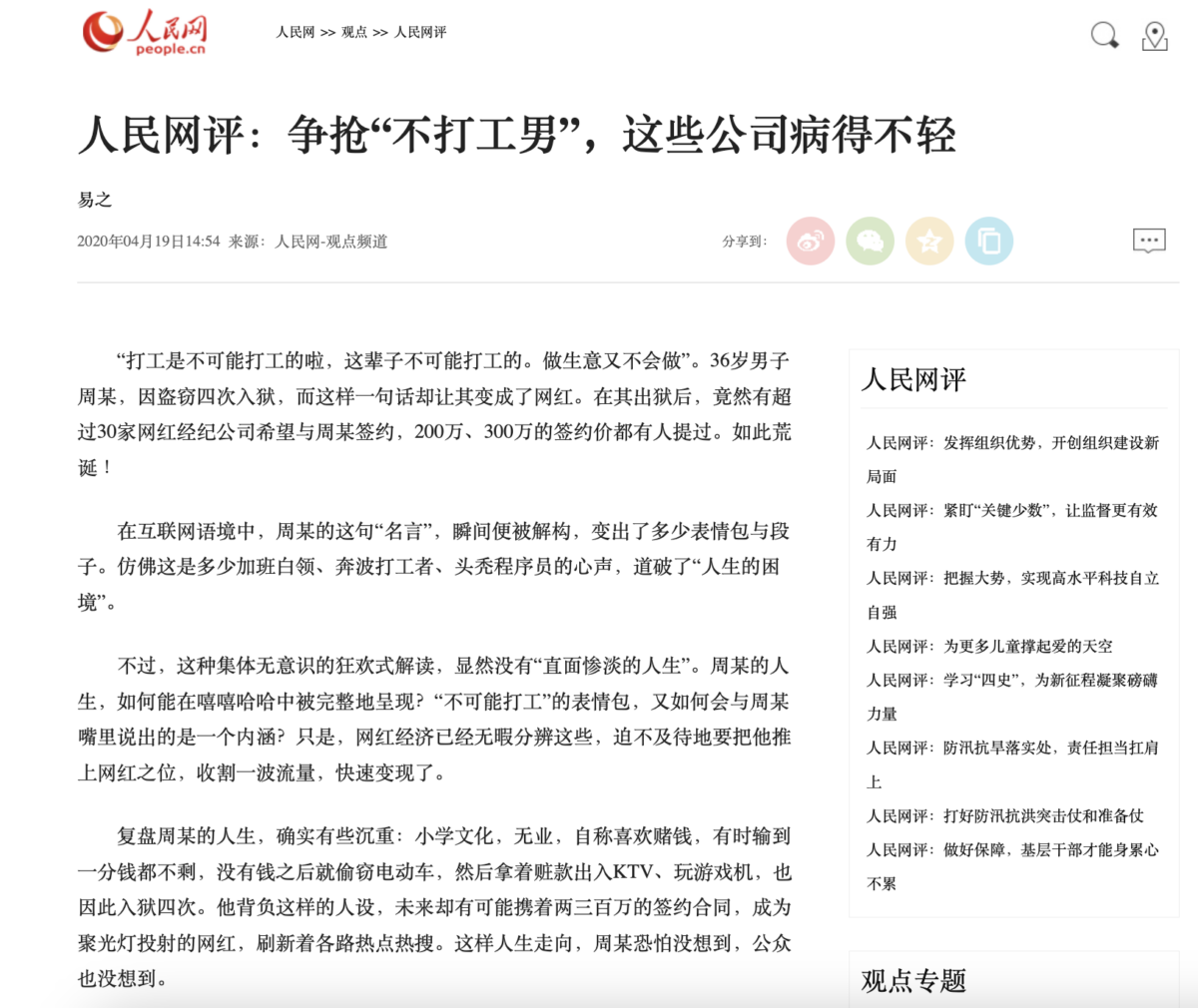

When Zhou was released from prison in April 2020, dozens of cars were waiting for him at the prison entrance and at his parents’ home. “This is like a dream,” he told a reporter as he was escorted home by police. Some of the cars waiting for him were full of superfans. Most of the people there, however, were talent scouts. They tried to stuff stacks of cash into Zhou’s hands, proffering contracts offering to compensate him up to 2 million Chinese yuan (about US$300,000) in exchange for signing him on as their newest live-streaming star.

But Zhou turned them all down, an audacious move that endeared him even more to his legions of fans. “I have said it before: I will not work for anyone. Signing a contract means I would become their employee. That would be eating my own words,” Zhou said. Instead, he said he was going back to farming. “You have to follow orders for everything . . . There is no freedom at all,” he said of his decision to turn down the contracts. “Farmers have freedom. It is up to you how much you want to plant.”

Zhou’s rejection cemented his cult status as an incorruptible iconoclast. However, soon after getting back home, he had a change of heart. His father was suffering from arthritis, and his mother was exhibiting early signs of dementia. He needed to find some way to pay for their care. Plus, Zhou’s agriculture plans to grow snow peas had gone miserably; years of migrant work in cities meant he was unfamiliar with farming.

He could see China was changing around him, but his family remained as poor as ever. The consumer technology sector had blown up in China during his last stint in prison. Even in his small farming village, people could pay for food and farming equipment with their cellphones. For entertainment, his friends sat around watching TikTok videos. Zhou learned that top live streamers selling goods like lipstick or popular snacks like snail noodles, a smelly local specialty from his home province of Guangxi, could earn hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. He decided to capitalize on his newfound fame, but on his own terms. He would make his own way on the Chinese internet, even if he didn’t totally understand how it worked just yet. Perhaps the internet would finally give him the freedom he craved: the opportunity to be his own boss and own his own labor.

I have said it before: I will not work for anyone. Signing a contract means I would become their employee. That would be eating my own words.

Zhou Liqi

Zhou could not imagine himself putting out anything that could be considered controversial. There were plenty of other people already doing that. China’s internet sectors had taken off, and even though censorship and political controls picked up in kind, dissent still rippled under the surface. Dissenters hid their samizdat content like easter eggs all over Chinese cyberspace. Some critical blogs hid their writers’ identities through disguised IP addresses and anonymized posts. Others taught internet users how to set up their own VPNs. Cybersecurity enthusiasts passed around manuals about which mobile chat and video conferencing apps remained available for download in the Chinese app store but offered end-to-end encryption or did not require real-name registration. That way, people in China could talk to one another anonymously and avoid using WeChat, which is intensely surveilled. On GitHub, the open-source coding repository, users archived manifestos and videos banned from Chinese sites, making them impossible to erase completely.

Much of the Chinese internet is pure entertainment, however. Overworked yet overwhelmingly connected online, China’s some one billion internet users spend inordinate time on their smartphones watching online stars—including live streamers—hawking the latest “it” bag or beauty products. Among the top live streamers was male makeup influencer Li Jiaqi, whose pucker once sold fifteen thousand lipsticks in five minutes, earning him the nickname the “Lipstick King.” Other live streamers specialized in comedy: one of the most popular was Teacher Guo, a thickset auntie known for her brash humor, profanity, and desire to find a younger boyfriend. These were the elite live-streaming ranks that Zhou wanted to join. He started an account on Weibo, a Twitter-like social media site, and he quickly racked up 3 million followers.

His populist appeal did not mean he was safe from censorship. The Party wanted productive citizens, ones who could contribute to the country’s technological race with the United States, keep building its skyscrapers, and birth multiple children who would become the country’s future workers. Zhou’s online ethos was the antithesis of the kind of citizen China wished to cultivate, for he represented a camp of people who celebrated unproductivity. “To build, market, and consume Zhou is to propagate a twisted social value that honors vulgarity and praises what is ugly,” wrote one cultural critic in Beijing, slamming the live-streaming companies that had tried to recruit Zhou out of prison. “These companies and platforms that hope to sign Zhou are endorsing the acts of stealing and reaping without sowing.” Zhou let the criticism wash over him. He had served his sentence and was ready to turn over a new leaf; a few editorials were not going to tank his live-streaming career. However, a new world was about to dawn, one that would bring with it new rules whose influence would reach even Zhou.

Zhou, the scooter thief, didn’t see how China’s shrinking space for expression would affect him. He was putting out personal videos that had nothing to do with politics. He was also dabbling with entrepreneurship. He co-founded a local electric scooter company in Guangxi province and sat on its board. Their scooters’ selling points involved an anti-theft security system designed and tested by Zhou himself to ensure thieves (like he had been) could not make off with them. He also opened a late-night barbecue joint, which became a hit with young men because the restaurant let them drink and smoke until dawn, shirts and shoes optional. Zhou kept an office on the restaurant’s second floor, and he wandered out frequently to partake in the revelries himself.

While his business ventures were tongue-in-cheek references to his past life, he was eager to prove that he was the kind of “positive energy” cybersecurity regulators wanted more of from the Chinese internet. He was fully aware of the mainstream criticisms of his persona, and contrary to his public reputation, he yearned to be a good person. His family’s poverty, his lack of a formal education, and his criminal record all shamed him. They made him feel he had not earned his fame. Moreover, fame itself was not the windfall he had thought it would be; he still felt like a rural outsider, parodied by the urban elite.

Zhou’s online ethos was the antithesis of the kind of citizen China wished to cultivate, for he represented a camp of people who celebrated unproductivity.

After being released from prison, he had been taken first to undergo “psychological counseling” with the local police. “Have you really changed?” he was asked. “I have earned my freedom, and I will certainly cherish it. I will not be stealing scooters anymore,” he promised. He also agreed to film a video with the police. “Please do not repeat this behavior again. I believe you will not return to that. You must always respect the law,” the officer is recorded saying. Zhou’s response is edited out, but he sits chastened across from them. His desire for self-reform was genuine.

That desire was great enough that he was now willing to risk alienating his core fan base. After he decided to embrace his internet fame, his first short video on the Chinese streaming platform Kuaishou was an apology. “I have to apologize. I did some bad things. I see online some people criticizing me. Some young people are copying me, learning from me. Do not copy me,” he tells viewers. “Just mind your own business. Live well.” In follow-up Kuaishou videos, Zhou performed charitable acts, delivering food and supplies to remote villages near his and offering his support to the country’s national poverty alleviation campaign. He acts stiffly in these videos, as if he is wary of saying too much. “All the leaves have fallen,” he observed during a photoshoot one cold Beijing autumn, then caught himself, worried the comment was too negative and could be interpreted as criticism of the country’s capital.

His reputational makeover pleased no one. His fans decried him for selling out. His critics accused him of trying to whitewash his former crimes. Life, Zhou mused, had been easier when he had just been an anonymous construction worker. Sometimes, he thought of Ah Zhen, the woman he wanted to marry before he had been arrested, before he had become a household name. “When we were together, I was really happy. That period of time was like living in a different world,” he reminisced in one of his videos. After getting out of prison, he had gone down to the local convenience store where Ah Zhen once worked, but she had quit, and no one knew where to find her.

The end to Zhou’s budding internet career came quickly. Soon after getting out of prison, he was listed by a state-run professional association as one of the influencers explicitly deemed to be a negative influence on society. “A former prisoner’s comments about contempt for the law, disdain for workers, and mockery of social rules in interviews with the media have become popular on the internet, leading many internet celebrity brokerage companies to ignore public order, good customs, and moral bottom lines,” the China Association of Performing Arts said. This critique was tantamount to a banned list. Social media sites immediately shut down Zhou’s accounts. Talent agencies refused to work with him. Zhou had been canceled — by the state. “Companies that ignore the [live-streaming] industry’s moral bottom line and disrupt its healthy ecosystem will be added to a negative list,” the performance association threatened.

Chinese regulators were concerned about disinformation, scams, excessive clickbait, and hate speech being proliferated on the internet — issues other countries, including the United States, are worried about as well. The difference is that Chinese regulators are increasingly focused on setting guardrails for content along moral and political lines, to better shape online content to fit state directives from month to month. Some stars who were politically canceled were even blurred out of videos and movies in post-production.

In the fall of 2021, China’s broadcasting regulators announced a ban on portraying “sissy men and other abnormal aesthetics.” As a result, live-streaming stars who had previously entertained millions of people with their fifteen-second clips found themselves canceled. Teacher Guo, the trash-talking auntie, had her accounts erased for “vulgarity.” Li Jiaqi, the Lipstick King, was temporarily pulled after eating a cake in front of cameras on June 4, the anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, because the cake looked a lot like a military tank. Over the next three months, a total of twenty thousand live streamers were “cleaned away” for “polluting” China’s internet, per internet regulators. The Party wanted feel-good clickbait, but nothing deeper. “Be a model of social morality and a builder of positive energy,” the National Radio and Television Administration advised.

Zhou quickly registered new social media accounts. He tried bringing more “positive energy” to the table. He posted videos encouraging students to apply for colleges and filming charity work he kept up in villages around his hometown. Invariably, a few weeks later, his accounts would be mysteriously shut down.

Zhou’s reputational makeover pleased no one. His fans decried him for selling out. His critics accused him of trying to whitewash his former crimes.

After watching his videos online for months, I wanted to meet Zhou, this leader of the lazy, a Robin Hood of the social media age, but who had been punished for trying to be good. Finding him turned out to be surprisingly easy. I called ahead to his late-night barbecue restaurant, whose manager confirmed Zhou still worked there and came in a few nights a week. Excited, my producer Aowen Cao and I flew from Beijing down to Guangxi province immediately and went from the airport straight to his barbecue joint. We continued our stakeout until midnight, when, exhausted, I made an executive decision to head to the hotel, though my producer left a handwritten note for the night manager to give to Zhou. We giggled as we handed it over, feeling silly and, suddenly, a little unprepared.

We found him on our second night in Guangxi. He was holed up in his upstairs office. To our surprise, he seemed to be in the middle of entertaining about a dozen police officers. His trade mark long hair and T-shirt stood out among the dark uniforms and crew cuts surrounding him. Zhou ushered us out into the hallway, looking harried. Aowen and I were both a little starstruck. He was a little thinner and sallower than the Zhou from his original 2012 viral video, but here was the spiritual leader of the slackers, in the flesh.

He was also looking much less relaxed tonight. Shutting his office door behind him, he explained to us that a group of police had surprised him with a health inspection. Additional security officers had called him earlier that morning warning him that two journalists from Beijing would try to interview him — and he was to refuse at all costs. Embarrassed he could not be a more hospitable host, he offered to treat us to dinner downstairs, where his intoxicated older brother — the spitting image of Zhou, but shorter — tried to lighten the mood with a drinking game. Soon, three pairs of men filed into the restaurant, conspicuously ordering fruit juice rather than the crates of beer the bare-chested clientele around us were throwing back. They acted more like plainclothes police, I realized. Flustered, I accidentally ordered rooster testicles for the hotpot. (So that was what “male chicken eggs” were!) We hastily left after seeing one of the men filming us with a handheld camera disguised as a phone charger. Back in Beijing, I wrote up our trip for a news piece on NPR, filed away my notes, and moved on to other stories.

Half a year later, Zhou threatened to sue me. He hired a lawyer to send a letter to NPR’s Beijing office, accusing me of slandering Zhou by falsely insinuating that he was under police watch. “Since Mr. Zhou Liqi was released from prison, he has been living with a grateful and positive attitude and has worked hard to establish his upright social image. His personal freedom has not been supervised and controlled by any department, within the scope permitted by law. Inside China, he can live as freely as an ordinary citizen and run his own businesses freely,” the letter read. The threat of the lawsuit took me by surprise. I had recorded a sympathetic portrayal of Zhou, and I largely empathized with his efforts to exude more positive energy. I had the feeling, however, as my trip had shown, that the idea for the lawsuit was not his but rather that of the security system that still looked after him. Soon after, I learned that I would not be allowed to re-enter China. Zhou’s restaurant eventually went bankrupt and shut down. Both Zhou and I, it seemed, were not positive enough. ∎

Excerpted from Let Only Red Flowers Bloom: Identity and Belonging in Xi Jinping’s China by Emily Feng. Copyright © 2025 by Emily Feng. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Emily Feng is an award-winning international correspondent for NPR covering China, Taiwan and beyond. Previously a foreign correspondent for The Financial Times, she lived in Beijing from 2015 to 2022, and then Taiwan from 2022 to 2024. Recipient of the Daniel Schorr Journalism Prize and the Shorenstein Journalism Award, Feng is the author of Let Only Red Flowers Bloom (Crown, 2025). She lives in Washington D.C.