Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

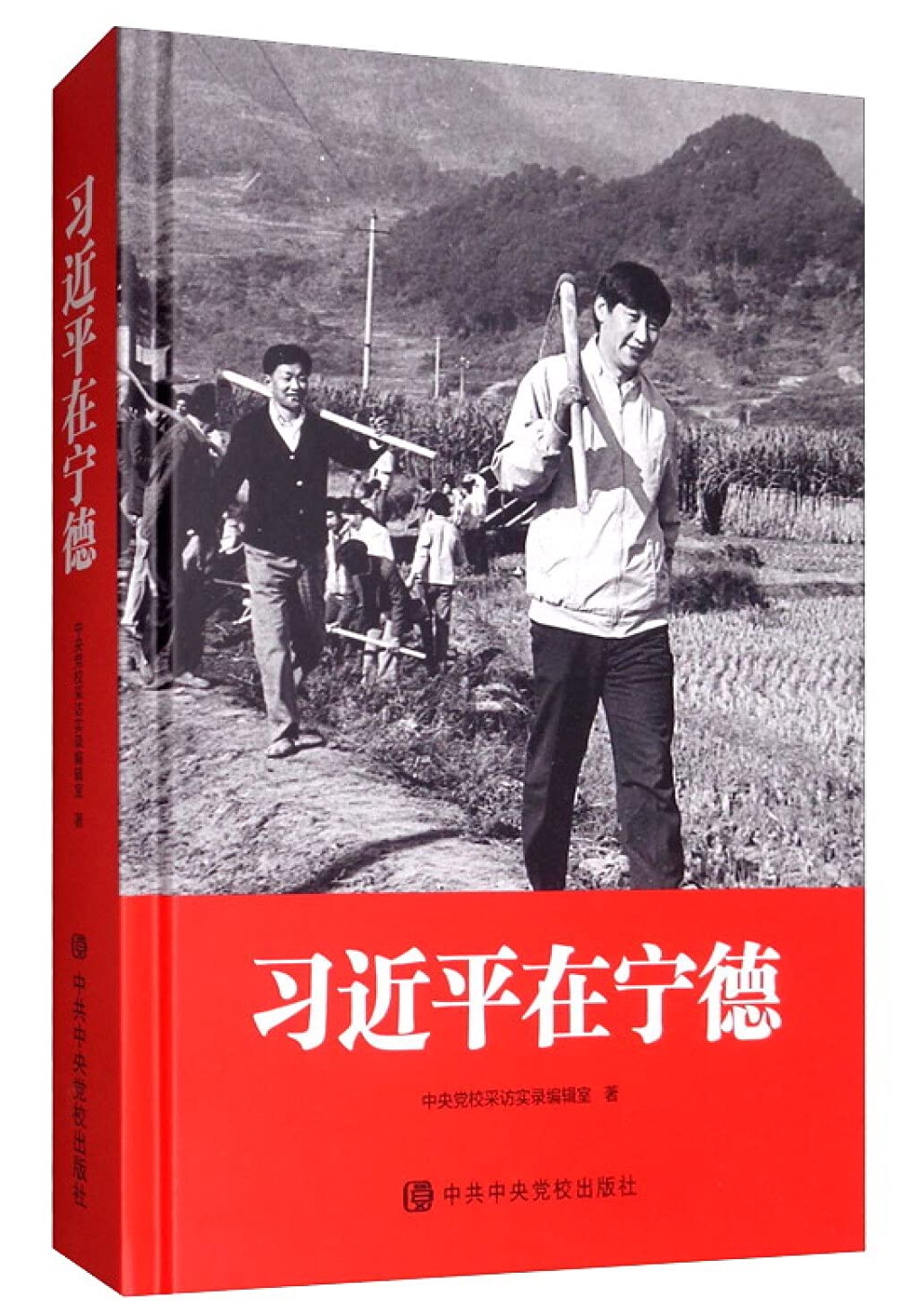

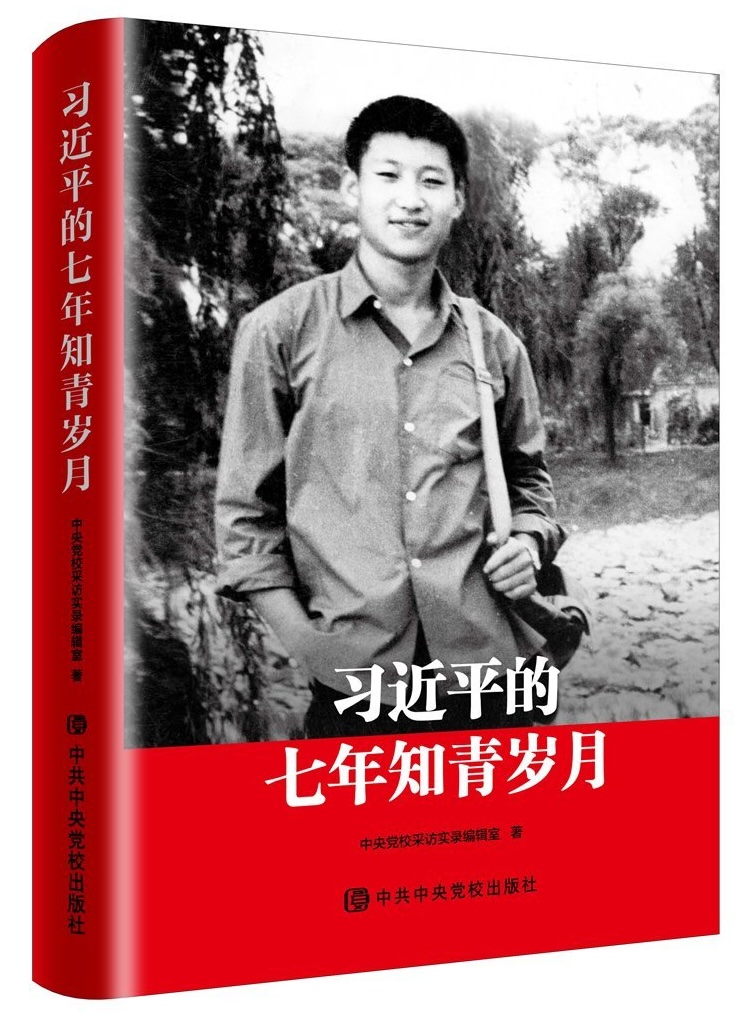

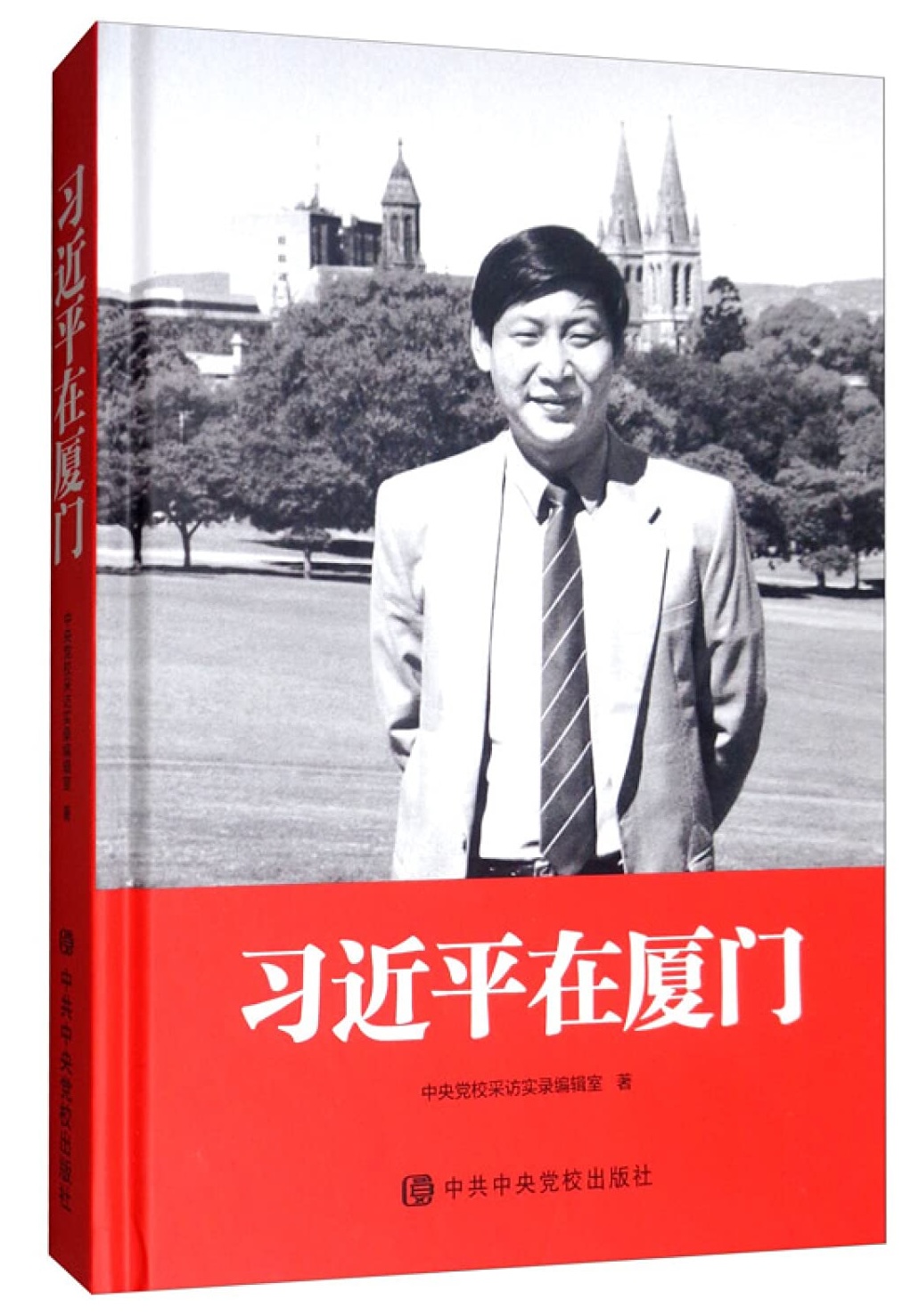

Reviewed: Xi Jinping’s Seven Years as a Sent-Down Youth (Aug 2017), Xi Jinping in Zhengding (March 2019), Xi Jinping in Xiamen (Jan 2020), Xi Jinping in Ningde (Jan 2020), Xi Jinping in Fuzhou (July 2020), Xi Jinping in Fujian (July 2021, two volumes), Xi Jinping in Zhejiang (Dec 2021, two volumes), Xi Jinping in Shanghai (Feb 2022): Central Party School Press (Chinese).

It was July, 1989, and Xi Jinping was a prefectural party chief in Fujian province. Motivated by his abiding concern for The Masses, he decided to visit one of the poorest, least developed places in his district. There were no roads so — staff in hand, wearing a straw hat — he led a delegation of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials in an arduous, five-hour hike to the remote village. Peasants hailed them joyfully as they trudged past, and Xi’s fellow officials marveled at his endurance. Once in Xiadang village, they heard reports by the yokels, ate a rustic lunch and trekked back out. Moved by the village’s impoverished isolation, Xi authorized a road to be built there, in one of the earliest examples of his enlightened vision to lift the Chinese people out of poverty.

This vignette is one of many related by provincial officials in Xi Jinping in Ningde (习近平在宁德), part of a ten-volume “oral history” series published in China from 2017-2022 for the edification of the cadre corps. The books would be standard official propaganda, extolling the virtues of General Secretary Xi Jinping, if not for the kaleidoscope of perspectives between their covers that bring the reader closer to Xi’s career in the provinces than the propagandists may have intended.

Take the same visit to Xiadang, retold from the perspective of plucky township secretary Yang Yizhou. Annoyed that a promised road was taking too long to complete, Yang invited Xi to come visit his village. He was worried that a two-hour walk in the summer heat would be too much for his city visitors, so he stationed his people along the path from the highway to offer tea and cool sweet soup. In Xiadang, he prepared a special standing shower for Xi to rinse off, and fêted him with a feast of the village’s very best delicacies, served on a historic bridge that had been scrubbed clean of ox manure by teams of soldiers and local women. The officials could have taken the same path out of the village but Xi insisted on a five-hour route instead, leaving his hot and weary entourage very glad when they reached their hotel that evening.

These vignettes eulogizing Xi Jinping’s public spiritedness are just a few among the 206 interviews published in the ten volumes of the series, tracing Xi Jinping’s life and career. Each volume features officials from a different period and location, from his sent-down youth in Shaanxi province during the Cultural Revolution (detailed in Xi Jinping’s Seven Years as a Sent-Down Youth 习近平的七年知青岁月) to his gigs as a mid-ranking official (in Zhengding, Hebei province, and in the coastal cities of Xiamen, Ningde and Fuzhou), and eventually as a powerful Party Secretary tapped for greater things (in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, then Shanghai).

The interviews, conducted by the Central Party School (中共中央党校), were produced for China’s 10 million-strong cadre corps, who are supposed to improve their job performance by studying how their General Secretary performed his. “Xi Jinping’s short time in Shanghai had a profound and lasting impact on Shanghai’s development,” gushed Duan Yicui, a former city official, in a typical contribution.

The lessons of the series are not subtle. Xi works assiduously; he does all he can to strengthen the Communist Party; and most of all, he remains close to The Masses. He is not haughty, accepts no special privileges, and never wastes time with empty speeches. He is dead-set against corruption, no matter how minor. He loves the people and talks to them at their level, asking how much their dinner cost or if their blankets are warm when he visits their humble homes, which he does often. Throughout his career, he has combatted poverty and lifted the people out of it. This last theme is especially prominent, because most of the interviews that make up this series were conducted in 2017, around the time that Xi launched a three-year campaign to eradicate absolute poverty.

Unsurprisingly, these books do not make for gripping reading. It is easy to imagine that their intended audience extracts enough of the general picture to recite a few key lessons at a study meeting, then moves on. That, dear reader, is formalism — one of the deadly sins that transforms a revolutionary Party into a stagnant bureaucracy. Formalism is something that Xi Jinping does not like, and (according to these books at least) has never succumbed to himself.

A close reading of the series, and a healthy dose of context, reveals more about Xi Jinping than the editors may have intended. Take Xi’s visit to Xiadang village in July 1989. A few weeks before, the bloody crackdown on Tiananmen Square removed the reform faction from power, and reinstated elderly revolutionaries with an old-fashioned view of the Party’s relation to the people. Xi’s five-hour trek established him as a young official of the revolutionary mold, unafraid to plunge into the countryside just as his superiors (and his father) had once done, back when they were young and the revolution was new. Reading between the lines, the account reveals an ambitious man, keenly conscious of the image he projects, unafraid of putting his followers through a little discomfort, and deeply embedded in the insular world of Communist Party officialdom where privilege is taken for granted and the people are props.

The lessons of the series are not subtle. Xi works assiduously; he does all he can to strengthen the Communist Party; and he remains close to The Masses.

The Central Party School in Beijing, which produced the series, codifies the ever-evolving ideology of the CCP, then transmits it to a constant rotation of cadres studying for promotion. Its publishing arm, the Central Party School Press (中共中央党校出版社), publishes official Party history and biographies of important figures, including a collection of reminiscences about Xi Jinping’s father, the early revolutionary leader Xi Zhongxun.

Starting in 2016, the Central Party School dispatched teams of interviewers to places where Xi Jinping had worked, interviewing current or retired officials in living rooms, retirement homes and Party-run guesthouses. Some interviewees brought sheafs of notes; others come across as extremely guarded. Many appear flattered to be sought out, and spoke at length of their own accomplishments while heaping praise on the General Secretary. Hopefully, the original transcripts — which must have run to thousands of pages — are preserved somewhere in the archives, because what was published was heavily edited. We know this because one sixth of the interviews were conducted twice, according to the dates listed for them.

The resulting testimonials were first published in the Party’s Study Times (学习时报) newspaper before being collated into ten identically-formatted volumes. Each interview is in Q&A format, and begins with a photo and short bio of the official who knew Xi. Almost every volume features one female interviewee, one military officer, and a journalist or two. Only one interviewee, a “red tourism” promoter named Jiang Shan, is associated with China’s leftist nationalists, a group whose goals often align with Xi’s. As with the Xiadang visit, multiple interviews covering the same events allow for an unintentionally rounded view. For instance, many Fujian bureaucrats praise Xi’s efforts to restore the birthplace of Lin Zexu, a Qing dynasty bureaucrat now admired by Chinese nationalists for resisting European incursions. Yet a close read of the differing accounts reveals that Xi was ready to bulldoze the mansion until a group of patriotic citizens intervened.

There is a long tradition of using oral interviews to convey a sense of authenticity in communist China. When Xi Jinping was in university in the mid-1970s, he would likely have encountered a body of hagiographic interviews praising Hua Guofeng, Mao Zedong’s now-forgotten heir, published after Chairman Mao died in 1976. Hua’s biographer Stéphane Malsagne wrote (in my translation from the French):

It was necessary to convince the Chinese that Hua Guofeng had all the skills to govern the country. To do so, lofty testimonials were gathered from people who had known or met him, from provincial chiefs to simple peasants in brigades, workers in factories or teachers in villages, including so-and-so the committee party secretary or such-and-such PLA veteran. … These compilations of testimonials were almost always presented along the same lines: first, a difficult or even dangerous situation at the local or provincial level, then the way in which Hua Guofeng surmounted it, followed by the eternal gratitude of these selected witnesses.

Oral interviews also feature heavily in Chinese history documentaries. Slow pans over still photos (à la Ken Burns) are interspersed by interviews with elderly revolutionaries, speaking in cracked voices and archaic dialects helpfully subtitled for today’s modern viewers. In Shaanxi province, where the revolution took root, I have seen longer text versions of these oral histories on sale in bookshops, all in more-or-less the same format.

CCP activists have used the same technique to highlight the suffering of Chinese comfort women who were sexually abused by the Japanese army during WWII. Their stories, intended to stoke outrage among today’s patriots, are inadvertently valuable records of the lives of poor young girls in the 1930s and 1940s, whose experiences would otherwise be utterly lost to history. In 2018, the Central Party School also published the Reform and Opening Up Oral History series, several volumes of interviews with reform-era officials in provincial China that preserve memories of change that took place far from the foreign investors or journalists whose accounts of China’s transformation are read in the West.

In short, the format has its virtues. Once the heavy varnish of propaganda is stripped off, the Party’s sanitized oral histories provide rare eyewitness accounts from people who are otherwise inaccessible. The Xi hagiographies especially benefit from needing to seem plausible to their intended audience, the cadre corps. While Xi is exemplary in all respects, he can’t be too generically wonderful or the result would be unbelievable. I have heard a sly summary of the books’ structure that is making the rounds of Chinese officials: Xi spends his first year in any given post touring around, the second year making speeches, and the third visiting Beijing. Then he gets promoted, and the cycle starts again.

Once the heavy varnish of propaganda is stripped off, the Party’s sanitized oral histories provide rare eyewitness accounts from people who are otherwise inaccessible.

Who is the real Xi Jinping? How did he get where he is, and what do the accounts contained in these oral histories tell us about him?

One preoccupation among China-watchers, many of whom believed Xi would be a liberal reformer, is whether accumulating power changed Xi, or if he had always been an authoritarian wolf wearing the sheepskin of reform. This series leans hard into the idea of Xi as a reform-minded young official who applied considerable energy to economic concerns. That theme is especially strong among high-ranking older interviewees — many of them now in their nineties — who were at the vanguard of new thinking inside the CCP in the heady days of the 1980s. The alert reader gets the impression that many initiatives they attribute to Xi were actually their own.

These older officials reveal how effective Xi was at carrying out their reformist agenda, and how attuned he was to their priorities. In the 1980s, Xi’s father was a powerful member of the reform faction in China, and the Party was committed to promoting his son’s career. Xi fils hammered through the reformers’ pet projects and adroitly massaged his image according to their values and prejudices.

Part of his appeal was never over-stepping the Party’s strict code of who is entitled to what perks, at a time when the flagrant materialism of the princeling class — descendants of early CCP leaders — was troubling the elders. In one anecdote, a status-conscious official got into a power struggle with Xi over who was entitled to the better apartment. Xi humbly ceded the apartment, thus winning the bigger battle.

There are also big gaps in the series. One of the biggest is how Xi transferred from the patronage of these older liberal officials to that of Jiang Zemin, who wooed the princelings in his bid to succeed Deng Xiaoping as the Party’s top leader. Jiang was General Secretary of the CCP from 1989 to 2002 and a powerful voice behind the throne during the Hu Jintao era and well into Xi’s first term. His support was essential to Xi’s rise.

We don’t know why the Central Party School redid about 30 of the interviews in 2020, but an educated guess involves the 19th Party Congress of October 2017, when Xi cleared the Politburo Standing Committee of men from Jiang Zemin’s faction and replaced them with his own loyalists. Jiang rarely appears in these books, despite hundreds of pages of testimonials, and nor does his lieutenant Jia Qinglin, who originally championed Xi in Fujian province.

The political scandal that may have cemented Xi’s usefulness to Jiang is only glancingly mentioned. In the late 1990s, a smuggling ring was exposed in Xiamen, the main port city in Fujian province. Its backers included the local government, the navy, the police, the customs bureau and, according to news reports at the time, Jia Qinglin’s wife. Xi took charge of sorting it all out — a delicate task that involved prosecuting the most obvious wrong-doers while shielding both Jiang and Jia.

In fact, the books indicate that purges were Xi’s special talent. Reading between the lines, he successfully challenged older, more experienced cadres as a young official during the late Cultural Revolution and again during the cleansing of the official ranks in the 1980s. He sorted out Jiang’s problem in Xiamen, and in return, Jiang’s faction backed Xi all the way to Zhongnanhai. Jiang was then caught off guard when Xi systematically attacked his men during his anti-corruption campaigns; the beneficiaries of the purges became the purged. Naturally, none of this is ever explicitly stated in the hagiographies.

While Xi was an effective tool for his superiors, the interviews reveal that he also attracted a very different cohort of younger men. Many interviewees are journalists or propaganda cadres, including speech-writers toiling away in provincial Party offices. They were star-struck to find themselves in a princeling’s orbit, and welcomed the task of promoting him. Perhaps this explains the tone of Xi’s administration, which has seen a cult of personality blossom. Granted, the Central Party School didn’t interview younger officials who rode the elevator with Xi Jinping from Fujian or Zhejiang to the halls of power in Beijing today. In fact, the signal-to-noise ratio in the series drops sharply as Xi rounds the corner of provincial officialdom, and enters the final stretch to central power in the early 2000s.

Other glaring holes in the series involve the lack of perspectives from foreign investors and private entrepreneurs, such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma or Wahaha’s Zong Qinghou, who were prominent figures in Zhejiang while Xi was Party chief there. In the go-go 1990s and 2000s, provincial officials bent over backwards to attract as much investment as they could — and so too, it seems, did Xi Jinping. But by 2017, when many of the interviews were conducted, Xi was cracking down on China’s richest entrepreneurs and relations with foreign companies were testy. If these topics came up during the interviews, they were left on the cutting room floor.

The books indicate that purges were Xi’s special talent. As a young official, he successfully challenged older, more experienced cadres.

During his 12 years (and counting) in power, Xi has refined a vision for China as a global power: militarily powerful and economically self-sufficient, technologically advanced, socially homogenous, and firmly under the control of an ideologically-driven Communist Party. In this respect he has been a reformer after all — if reform means the root-and-branch reorganization of a fragmented Party, undisciplined military and stagnant state sector into coordinated organizations, all singing from the same songbook and ready to take their marching orders from Beijing.

Was this Xi’s vision all along? Will it remain his preoccupation? Strangely, this biography series doesn’t really say. Interviewees tie his career to the themes of his first and second terms, especially the need to root out corruption and “rejuvenate” (复兴) the Party — but their examples in support of these trends are thin.

Whole sections of Xi’s biography are skipped. There is no Xi Jinping at the Central Military Commission (where he worked from 1979 to 1982, as secretary to Central Military Commission head Geng Biao) and no Xi Jinping at the Central Party School (which he led from 2007-2012, while he was the nation’s vice president). You would think that the cadre corps could derive much merit from studying how a young Xi enacted a vision for China’s military readiness and power projection, or how, as a mature official and heir apparent, he retooled ideology to serve the needs of the Party. But no. Aside from some generic praise on these sensitive topics, the series avoids them.

The largest elision is, of course, what happened after Xi Jinping took the throne, becoming CCP General Secretary in October 2012. The series concludes in 2007, when Xi leaves Shanghai to take up the crown of heir apparent and join the Politburo Standing Committee in Beijing, although some interviewees offer anecdotes that extend into Xi’s second term. Like his stint at the Central Military Commission, the years after Xi reached the center of the Party are too sensitive to air to the cadre corps at large. Do the faithful really need to learn how he sparred with his predecessor Hu Jintao, or why he fired the PLA’s most decorated generals? Presumably, it was safer for the series to focus on how General Secretary Xi doesn’t stand on ceremony when he dines with the peasants.

Ultimately, in Xi Jinping’s life as in this collection of testimonials, even the most alert observer cannot color in the blanks of what is left out altogether. Are the jigsaw pieces missing because they are the most important and therefore the most sensitive, or is there simply no prior evidence for some of Xi’s preoccupations after he took power? These are the limitations of trying to understand Xi Jinping, the person, through official publications such as this series or The Governance of China, a collection of his speeches. The series is fundamentally propaganda, not history, and the fine art of propaganda bases itself on carefully selected facts, spun to reflect what its creators believe their audience needs to hear.

There are a few tension points alluded to. Some interviewees point to the existential crisis of identity that gripped the Party around 2012, and the anxiety over whether one-party rule could survive China’s new prosperity. “We needed to be more confident, resolutely traverse this period, make it through the middle income trap, and achieve victory,” said Yan Zheng, a retired official in Fujian. Another worry was whether the rest of the world would torpedo China’s rise. Since Xi took power, China has faced “complex international conditions” and “we all sweated a little over it,” former Fujian environmental official Li Zaiming told the interviewers, before concluding:

But Xi Jinping had political decisiveness. He took the situation in hand and pivoted to a new front. Now we can see a bright new vista.

Ultimately, a key takeaway from the interviews is that mid-ranking CCP cadres care a lot about economic reform and the future of their nation. They want China to be technologically advanced, and respected by foreign powers. They want to solve the intractable problems of poverty and incompetence. They yearn for a leader who is down to earth, deserving and capable, and a Party that is rational, cohesive and meritocratic. They want the Party they serve to align with the nation they love.

Is Xi the leader that the Party’s rank and file yearn for? From the villages of Shaanxi to the halls of Zhongnanhai, the point of this series is to show that he is. ∎

Lucy Hornby lived in China for 20 years, reporting for The Financial Times and Reuters. She is currently a non-resident Senior Associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).