Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Fei Dao (飞氘) is a Chinese science fiction writer born in 1983. I first met him in 2012 in Beijing, at a Christmas party hosted by the translators’ collective Paper Republic. Later, I ended up translating two of his short stories: “The Storytelling Robot” (reproduced below) and “An End of Days Story.” Both have a fairy-tale feel to them, infused with a quiet humor and deep melancholia that attracted me as a challenge to translate.

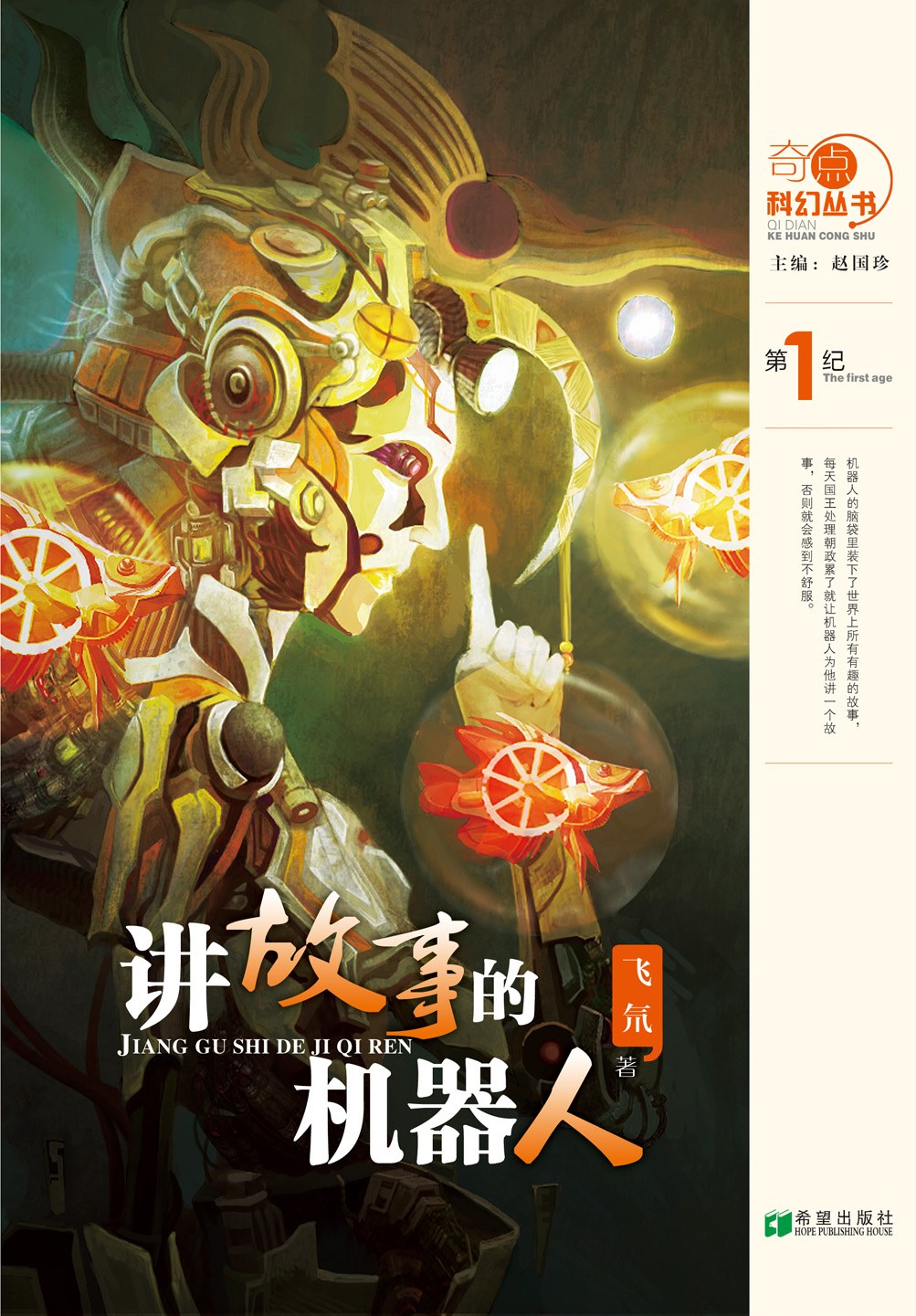

Fei Dao is a pen name: the original characters (飞刀) meant “flying dagger,” which he thought sounded cool, but he later changed the second character to 氘, a chemical element (deuterium) also pronounced dao. Then a scrawny, bespectacled PhD student, he was a recognizable science fiction geek type. I could picture his childhood growing up in a coal town in Inner Mongolia, nose buried in a copy of Science Fiction World (科幻世界) magazine while everyone else played basketball. Now he is the author of four collections of sci-fi short stories, including The Storytelling Robot (讲故事的机器人, 2013), and received his PhD in comparative literature at Tsinghua University, where currently teaches Chinese literature and sci-fi.

Below the story is an interview I conducted with Fei Dao about his entrée into science fiction, the genre’s storied history in China, and what makes it special. We hope you enjoy both as an open sesame into his work.

— Alec Ash

***

The Storytelling Robot

Once upon a time, there was a King, who loved neither the beauty of his domain nor its women, but only took pleasure in listening to stories. He kept a storyteller in his palace, but the number of tales that any one person can know is limited, and whenever a minstrel had told them all the King would exile him far, far away. After a while, no one dared tell any story.

And so the King convened the most ingenious scientists in the land, and ordered them to build a storytelling robot. At first, the stories that the robot told were lifeless, but it had the ability to learn independently, and under the supervision of the scientists it slowly perfected the quality. Its brain was installed with every story that was known of, and each night the King, tired from the affairs of state and wanting to relax, ordered the robot to spin him a yarn. If the King could not hear two or three short stories before retiring, he was not able not sleep.

One day the King, reclining in the imperial bed, closed his eyes and prepared to enjoy a new and fabulous story. The robot began, “In a distant town there was a famous thief known as Crack—”

The King furrowed his brow, opened his eyes and interrupted the robot. “You’ve already told this story,” he said. “Tell another one.”

Again, the robot began, “Once upon a time there was a King who, for a son, had a pig—”

Although the robot’s tone was most comical, the King frowned. “It seems I wasn’t clear,” he said. “Tell a story that you haven’t told before.” Once more he shut his eyes, somewhat displeased.

The robot silently checked its database, only to discover that it had already told every story it knew. “Does this mean you have nothing at all for me?” the King said in disbelief. He thought for a moment, then asked, “Can you invent a new one?”

And so the scientists got back to work, vastly expanding the mental capacity of the robot so that it could process more complex operations. Through great effort they taught it the concept of invention, converting its function from narration to creation, and the robot finally understood that that which did not exist could be fabricated. The first story it invented was utter nonsense, but the scientists were delighted at the breakthrough.

The robot’s ability to learn was unparalleled, and with the help of its creators it analyzed its databank of stories to create a set of scientific laws for storytelling — a model that would later become world-famous. But the mathematical nature of this model was so overwhelmingly complex that only the robot could make head or tail of it. With systematic practice, it finally invented its first high-quality story. The King was most satisfied, and issued the command, “Remember, you are only to tell me the most marvellous tales.”

Whenever the King was in a good mood, the robot would in a loud, clear voice tell a sentimental yarn, and the King would sigh with emotion. So moved was he by the misfortunes of those in the story that he would issue impulsive decrees to lighten the burden of the common people. Whenever the King was in a bad mood, the robot would vividly narrate a comic tale, and as the King listened he would cry with amusement, his anger abating until the harried court officials breathed a sigh of relief, and everything was at peace once more.

The robot’s storylines grew ever more wonderful, surpassing the most talented of human minstrels. Adhering to rigorous mathematical laws, its stories were always of the most succinct structure, with no sloppiness whatsoever, and the complexity of the scientific model prevented any new stories from seeming familiar. Some of them might be called classics, and even the King asked to hear them again. Yet all the while, the robot stuck to stylistic formality. Every story began, “Once upon a time,” and ended, “That is all, your Majesty.”

Every night, when the King put away his imperial correspondence and issued the order to begin, the robot would softly say, “Once upon a time.” At that the whole palace went quiet, everyone in their appointed place, not disturbing the inner chamber until they heard the words, “That is all, your Majesty,” when they tentatively suggested the King retire for the night.

Day after day, the robot invented new and astonishing stories without rest. But the King was a clever man, and even if the stories seemed ingeniously different, he still had a nagging feeling that they were made of the same cloth. And so one night, when he was in a particularly foul mood, he commanded, “Tell me the most marvellous story in the whole world.”

A hush fell. This time the robot didn’t begin at once, and was struck dumb in thought. The King tried his best to be patient, while the court started to feel uneasy. All of the concubines and attendants prayed that the robot would tell this unrivalled tale without hitch, or else the King would surely be angry. When, finally, they heard those welcome words, “Once upon a time,” everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

“Once upon a time,” the robot began, “there was a gifted King, who in order to rule everything under heaven used the sharpest material that exists to create an invincible army.” As the story progressed, the whole court was entranced, and the King quite forget everything else, listening with all his might. The army defeated powerful enemies and terrifying beasts, and had many a bizarre adventure, vanquishing city after city until finally they arrived at the last unconquered capital. Yet the King of that country had used the most durable material that exists to create an unconquerable city wall. “On the verge of battle,” the robot went on, “the two Kings bowed in respect to each other, at which the invincible army lifted their pikes and rushed towards the unbreakable city wall—”

The robot stopped suddenly, and the King was jolted back to reality. Vexed, he commanded, “Continue.” The robot’s eyes flickered for a moment, but it still didn’t open its mouth. “Why did you stop?” the King asked harshly. The court trembled while the robot calmly answered, “Your Majesty, this story can have two endings, but I haven’t yet calculated which is the most marvellous.”

“Could it be that they are both equally splendid?” the King said, displeased.

“Affirmative,” the robot answered. “The proximity of both endings to the ideal parameters of the scientific model of storytelling is exactly equal. This is the first time this has happened.”

“In that case, tell both endings,” the King ordered.

“Impossible, your Majesty. In accordance with your instructions, I must narrate a single perfect story for you. This is my duty,” the robot replied placidly.

“No, I reissue my command. Immediately continue the story, no matter which ending you choose.” The King’s tone was cruel.

The light in the robot’s eyes dimmed to blackness, and went out. That night, no one heard the words, “That is all, your Majesty.” The palace was on tenterhooks all night, and the King didn’t sleep a wink.

The robot’s storylines grew ever more wonderful, surpassing the most talented of human minstrels.

By daybreak the scientists had finally repaired the robot, but cautiously warned the King, “You had better not again give him mutually contradictory orders.”

The King asked blankly, “Is there no way?”

“Your Majesty,” one scientist said, “his ability to fabricate stories fully illustrates that he now possesses a human mode of thought, and his memory programming is interwoven together. If we simply erase your previous order, we’re afraid that all his stories will also be lost.”

“Quite,” another added. “We located that particular part of his memory circuits and tried to externally reinstall his stories, but I’m afraid all we got was a stream of nonsensical data.”

“What’s more,” a third piped up, “he seems to have adopted some form of deeply held belief, a principle even, that arose unexpectedly from his formidable processing power. We’re not quite sure how this came about, but you had best not compel him to violate it.”

“To conclude,” the final scientist flattered, “under your Majesty’s training, he has evolved to an extremely complex state, far exceeding the scope of our understanding.”

“Useless idiots,” the King said simply, and left.

The King spread word throughout the land that whoever could complete the tale would be richly rewarded. The whole kingdom was fascinated by the unfinished story, and many gifted minstrels came forward to narrate all sorts of endings for it. The King thought them all very fine, but none could be called the most marvellous in the world — and even then, all he really wanted to know was the ending buried in the robot’s brain. The King rewarded the storytellers, then sent them away.

All the while, the robot continued to carrying out his duties. Each night he told many wondrous yarns, and the King sighed and laughed along with them as before. But they weren’t entirely satisfying, because deep down the King was still thinking of the unfinished story, the perfect ending for which the robot hadn’t yet decided on.

As the years went by, the robot grew more to resemble a human, while the King in turn grew old, and his temper quieted. He even grew to be fond of the robot in a vague way, and sometimes the two would chat together, each unerringly polite to the other. After all, in all the court the King had not a single friend.

One night, the King asked in a tired voice, “Have you still not thought of how to end that story?” The robot was silent for a moment, then calmly answered: “Your Majesty, perhaps you may not believe it, but I can also suffer. Every time I think that to use one ending I must abandon the other, a current of regret flashes through my brain circuits. I don’t know which ending to tell you. I can’t make up my mind.”

“You truly are an artist,” the King smiled, then lay down sick upon his bed, and never rose from it again.

The King’s illness worsened each day. The medicine of the imperial doctors was to no avail, and the people whispered that he would die soon. One evening, when the royal bodyguards had withdrawn, only the robot remained, tirelessly keeping watch over the King. In the darkness, struggling to calculate an ending for the unfinished story, he waited for the King to wake and ask him to tell a little tale.

At daybreak, the King opened his eyes and fixed his gaze on the robot. In a feeble voice he said, “That story of yours—”

“Your Majesty, I think perhaps there could be a third ending,” the robot replied softly. The King shook his head. “No, it doesn’t need an ending.”

The last will and testament of the King left all affairs of state neatly tied up. The only thing it didn’t specify was what to do with the storytelling robot. The King’s son was a diligent and kind ruler, but he liked sports, not stories. Out of respect for his father, he decreed that no man had the right to know the ending of the unfinished story. The scientists washed clean the robot’s memory, and put him on display in a cabinet in the imperial museum. The story’s final mystery remained unsolved.

That is all, your Majesty. ∎

***

Q&A

Alec Ash: When did you start writing science fiction?

Fei Dao: When I was in school, 16 or 17, I started to read a lot of sci-fi. I read the magazine Science Fiction World and became more familiar with sci-fi literature. I liked it because there was a lot of imagination and novelty in it. At that time, my dream was to become an author. When I started out, I didn’t think at all about writing science fiction. Back then I felt sci-fi was very difficult to write, and needed some knowledge of science, so I could only appreciate it but not write it myself.

Like many post-80s authors [born after 1980], I started out writing campus stories about young people in school. But I couldn’t get them published. One day in university, I wrote a science fiction story on the side and sent it in to Science Fiction World. I was just giving it a go, I had no idea that that first story would get published in 2003. A year later, I had another idea, and that second story also got published. So that encouraged me, and I started writing sci-fi.

How popular is sci-fi in China?

In my opinion, it’s mostly popular among young people. This has a big connection to Science Fiction World, because a lot of students at middle school and university buy that magazine. It has a very large readership. But after people graduate and start to work, most people don’t read science fiction. They think it’s just youth literature and that grown-ups should read more mature stuff, not childish stuff.

What do you think?

Of course I don’t think it’s childish literature. But Science Fiction World is, after all, for young readers. The whole feel of the magazine is like that. So while there is lots of mature science fiction for grown-ups, the readers are still mostly young.

I feel lots of people are prejudiced against sci-fi. They think that if you’re a certain age and still read sci-fi, that’s immature and unrealistic, like you are letting your fantasies run wild. So I think that prejudice is a problem. But now that The Three-Body Problem (三体, 2008) by Liu Cixin has been publicly praised, I hope that is changing people’s opinion.

Who are the Chinese authors we should read?

The most popular authors now are Liu Cixin, Han Song and Wang Jinkang. Those three are the most famous at this time. Some people jokingly call them “the three generals.”

What is unique or particular about Chinese science fiction?

Chinese sci-fi has about 100 years of history. When it started, in the late Qing dynasty around 1902, it was chiefly concerned with the problem of bringing ancient China into modernity. At that time, Liang Qichao translated sci-fi because he thought it would be beneficial for China’s future, as something that could popularize scientific knowledge. And Lu Xun thought that if you gave ordinary people scientific literature to read, they would fall asleep. But if you blended scientific knowledge into stories with a plot, it would be more interesting, and the people could become more modern.

So at that time science fiction was a very serious thing to do in China. It could allow ordinary people to get closer to modern scientific knowledge, and served as a tool for transforming traditional culture into modern culture. It played a very important role, and had a serious mission to accomplish.

Chinese sci-fi has about 100 years of history. When it started, in the late Qing dynasty around 1902, it was chiefly concerned with the problem of bringing ancient China into modernity.

Today, there is a commercial publishing market for sci-fi, and people don’t have such weighty expectations of literature, yet authors are still discussing serious topics. Three-Body by Liu Cixin or Subway (地铁, 2011) by Han Song both have many reflections about the direction of this country and of humanity. So this kind of writing can convey concerns about the future, or discuss the current situation in China.

For example, Han Song’s Subway is about a subway station. In China, subway systems are an emblem of modernization. Many cities in China are building huge subway systems, because to have one or not is the standard of a city’s modernity and development. So in discussing this symbol, Han Song seized on a sensitive point. After publishing Subway, he wrote another book called Highspeed Rail (高铁, 2012), another emblem of technological innovation. So Han Song is consistently concerned with the potential catastrophes of the process of modernization.

Liu Cixin, on the other hand, is expressing a grander feeling of the universe in the tradition of Western sci-fi. In doing so, he wants Chinese people to look up at the sky and not just be concerned with earthly matters. The mainstream of Chinese literature is about real-world subject matter, such as the countryside or urban life. Very few people are concerned with the fate of humankind, the future of the universe, or even aliens. These things are themselves alien to Chinese readers, but can be introduced through this kind of writing.

I think that the key theme of Chinese science fiction, no matter how it develops, is how this ancient country and its people are moving in the direction of the future.

What is the relationship between Chinese sci-fi and the censorship authorities?

I’m an author, not a magazine publisher, so I’m not sure precisely what the relationship between them and the censorship department is. But in China, no matter what the subject matter of literature is, you have to communicate with the censorship department. For example, if you write realistic fiction about a sensitive subject, you’ll also come up against objections. It’s the same for sci-fi.

Is there a big Western influence on Chinese sci-fi?

Science fiction is a new variety of literature in China. Before a hundred years ago, it had no frame of reference, so Chinese sci-fi authors just studied Western works. Of course there were native influences too, but in the end the learning process was from the West. Chinese sci-fi writers today have also read a lot of Western sci-fi. They’re very familiar with it, and it’s given them a lot of inspiration. For example, Liu Cixin emphasizes his admiration of Arthur C. Clarke.

What are the other main influences?

There’s also a big influence from Japan. Historically there were a lot of Japanese sci-fi stories translated into Chinese. Jules Verne was also first translated from Japanese into Chinese. And contemporary Japanese sci-fi, for example Japan Sinks (日本沈没) by Sakyo Komatsu, is very popular in China. Anime and manga are also an influence, but only starting from the post-80s generation, because that is the generation where TV shows began to become popular.

Another big influence on Chinese science fiction is Soviet sci-fi. Especially after 1949, when China had less connection to the West and more connection to the USSR, the most famous Chinese sci-fi authors were most influenced by Soviet sci-fi with communist themes. So there are three big influences: the West, Japan and the USSR.

Who are your biggest influences?

I’ve been influenced by a lot of non-science fiction writers, and I’ve read classic Western sci-fi such as Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov. But when I was young, one of the works that most subtly influenced me was a novella by Ted Chiang (姜峯楠) called “Tower of Babylon” [in Stories of Your Life and Others, 2002]. That story gave me a new understanding of science fiction — that it doesn’t have to be just about technology.

In the story, they built a high tower in Babylon that became a world with different floors and people living inside. They built it bit by bit, until it reached the top of the sky. Then they burned through the sky, and the protagonist entered into the heavens, where there was water and a sandy shore. This world was cyclical — you arrive in the heavens and it’s like the seabed. It’s hard to explain, but this was a very serious science fiction or fantasy story, and it opened up a large imaginative space for me.

Do you think sci-fi is important?

I do. I think that imagination is very important. People must preserve a curiosity about the future. Many people, because of everyday pressures, don’t have the time or the energy to care about things that don’t seem to be about everyday reality. But I think that to be curious is very important, and so is sci-fi. ∎

The Chinese version of this story first appeared in 讲故事的机器人 (希望出版社, 2013). A version of this post also appeared in different forms at the LARB China Channel. Header: ChatGPT.

Alec Ash is a writer focused on China, and editor of China Books Review. He is the author of Wish Lanterns (2016), following the lives of young Chinese in Beijing, and The Mountains Are High (2024) about city escapees in Dali, Yunnan. His articles have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic and elsewhere. Born and educated in Oxford, England, he lived in China from 2008-2022, and is now based in New York.