Reviewed: Breaking The Engagement: How China Won & Lost America by David Shambaugh (Oxford University Press, June 2025).

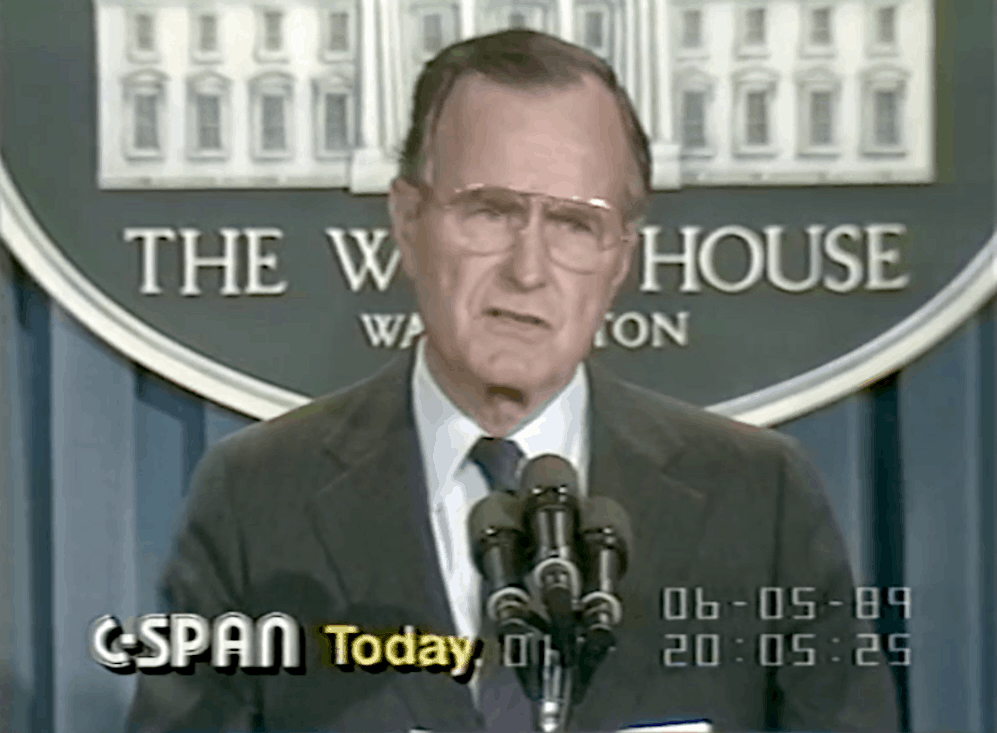

The U.S. didn’t adopt engagement as its formal policy toward China until a crisis threatened to destroy relations. After Chinese troops killed protestors at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, popular revulsion in the U.S. was so severe that Congress seemed poised to blacklist Beijing. Searching for a rationale to explain why the U.S. should continue to work with China, President George. H.W. Bush latched onto the notion of engagement.

“Now is the time to look beyond the moment to the enduring aspects of this vital relationship for the United States,” he told a press conference the day after the shootings. “It is important to act in a way that will encourage the further development and deepening of the … process of democratization,” he said. “I happen to think that the commercial contacts have led, in essence, to this quest for more freedom.”

That belief — that tying China tighter to the U.S. commercially would lead to greater political and economic liberalization — became the heart of U.S. policy for over 30 years, until the first Trump administration rejected it as dangerously naïve. During the engagement era, various presidents occasionally sought to distance Washington from Beijing, but time and again they embraced the idea that the U.S. could best influence China by lashing the two countries closer together. Over time, U.S. businesses, universities, philanthropies and other institutions also embraced their Chinese counterparts, creating a coalition that reinforced engagement.

David Shambaugh, a China specialist at George Washington University who has written prolifically about China over the past 40 years, recounts the rise and fall of engagement policy in Breaking The Engagement: How China Won & Lost America (Oxford University Press, June 2025). It’s a valuable contribution to the history of U.S.-China relations, reflecting his deep knowledge of the subject and extensive research, though the book has significant flaws. Among the book’s many strengths, Shambaugh shows how engagement reached deep into the American psyche to what he calls America’s “missionary complex.” Since the earliest days of the Republic, businessmen and missionaries have sought to remake China in America’s image; engagement is the latest example of that impulse.

This evangelizing works when China follows America’s lead, but fails when China rejects outreach as paternalistic or scheming. Shambaugh cites China scholar Harry Harding’s astute observation that both China and the U.S. “believe that they are exceptional, although in different ways. Americans think their country is the exceptional embodiment of universal values; Chinese think their long history and unique culture shows that they can be an exception to those Western values whose universality they reject.”

Shambaugh highlights the work of people often overlooked in the development of engagement policy. For example, the State Department official Roger Hilsman drafted a speech in 1963 for President John F. Kennedy — just when the split between China and the Soviet Union was becoming more public — announcing that the U.S. was open to a “new approach” to China. Kennedy was assassinated before the speech was finished; Hilsman still gave the talk a few weeks after JFK’s death. While the new openness garnered press attention, Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, showed little interest in following up.

Yet Shambaugh largely fails to weave in Chinese reactions to Washington’s pursuit of engagement over the years, leaving the Chinese viewpoint mainly to a 21-page appendix. He also doesn’t spend enough time analyzing the crucial role American business played in lobbying for engagement and sustaining it. A big reason that engagement began to fray was because many U.S. businesses became disenchanted with the Chinese market, where they struggled to make a profit and their trade secrets were stolen.

Shambaugh dismisses business leaders as shills for Beijing and portrays engagement as an economic disaster for the United States. He says that perhaps the U.S. needs to revive the 1917 “Trading With the Enemy Act,” which gave the president power to prohibit trade with enemy nations during wartime. In response to the claim of gains from trade with China, he writes:

Tell that to the millions of American workers who lost their jobs because of outsourcing manufacturing to China, or to the tens of thousands of American farmers who have lost their farms before China became a major soybean importer.

While factory workers in the American southeast and upper midwest surely took the brunt of the so-called “China shock,” any reasonable accounting of engagement would also note the gains in American living standards in the form of low-cost and varied imports which helped to hold down inflation. Competition from Chinese companies has also pushed American firms to innovate, as U.S. artificial intelligence firms are finding out as they work to stay ahead of China.

Regions of the U.S. affected by Chinese imports in the early 2000s have recovered somewhat, according to the economists who co-authored the China shock research. Manufacturing jobs lost to China, in industries like furniture and electronics, have been replaced by jobs in healthcare, education, logistics and other sectors less affected by trade, though the work often pays lower wages. Despite the pain wrought by Chinese competition, the U.S. economy is still flexible enough to create jobs and ameliorate some of the losses.

Surprisingly, Shambaugh doesn’t explore whether engagement produced any gains. Some argue it did. Former CIA and Pentagon chief Robert Gates, a gimlet-eyed observer of U.S. foreign policy, said in a Wire China interview with me (later anthologized in an e-book) that the “irony” of engagement is that it might have been succeeding in undermining CCP rule by creating alternative centers of power. “Xi felt like the Party was losing control, with all of the entrepreneurs and the Jack Ma’s of this world,” Gates said. “That’s one of the things Xi has been trying to reverse.” Some Chinese scholars and officials worried that Gates might have been right, seeing engagement as a trap to let in Western ideas and influence.

For Shambaugh, the story of engagement is a personal saga. He was present at many important meetings between the two sides, usually as an academic observer. He even suggests he might have saved President Reagan from an assassination attempt in 1984, when he told U.S. officials — while he was studying in China — that a Venezuelan and a Palestinian student were discussing shooting Reagan at the Great Wall Sheraton hotel in Beijing. (All students from developing countries were put on a train out of town during the presidential visit.)1 Less dramatically, he claims he was one of the first academics to describe China and the U.S. as “competitors.”

Ultimately, Shambaugh pronounces engagement “D-E-A-D. May it rest in peace.” For him, the demise couldn’t have come quickly enough. He argues that engagement failed to produce the reforms in China that the U.S. sought, especially after Xi Jinping took power, and U.S. policy makers became too defensive in confronting an increasingly aggressive China. Shambaugh favors what he calls “comprehensive” or “assertive” competition as a lodestone for U.S. policy, where cooperation takes second place in policy priorities. Yet to examine the legacy of engagement — or perform an autopsy on it — we must first look back to understand its origins.

Since the earliest days of the Republic, businessmen and missionaries have sought to remake China in America’s image; engagement is the latest example of that impulse.

Few observers envisioned full-fledged engagement with China at the time of Nixon’s path-breaking trip to Beijing in 1972. For both countries, working together militarily to weaken the Soviet Union was reason enough for rapprochement. Chinese officials were wary of more fulsome ties; they remembered Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’s call for the “peaceful evolution” of communist systems in 1959, which they interpreted as trying to undermine their rule. In the U.S., some State Department officials saw little opportunity for commercial gain, Shambaugh reports. But Henry Kissinger recognized the need for a sturdier foundation of Sino-U.S. relations, insisting that economic, cultural, media, sports and scientific exchanges be included in the Shanghai Communique of 1972, which laid out terms for normalization of relations.

U.S. policy toward China over the next two administrations (Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter) continued Nixon’s national-security-plus approach. The two countries were expanding commercial, military and non-military exchanges. President Carter wasn’t looking to change China domestically, Shambaugh writes, though he was seeking a longer term relationship. As Secretary of State Cyrus Vance wrote in a confidential memo to Carter before he met with Deng Xiaoping in 1979: “To the extent that the Chinese become part of the community of primarily non-Communist nations at this time in their development so will our ties with China be more enduring.”

President Reagan, a longtime anti-communist supporter of Taiwan, initially was less enamored of China. But during his administration, relations warmed with Beijing. His two-hour session with students at Shanghai’s Fudan University was broadcast live on television. The two governments signed dozens of bilateral agreements, and U.S. businesses and universities strengthened their ties. During Reagan’s second term in office, from 1985 to 1989, U.S. total trade with China nearly doubled to $13.5 billion. Shambaugh calls the period “the glory years of Sino-American relations.”

The euphoria was short-lived. On June 4, 1989, PLA soldiers gunned down protestors in Tiananmen Square, some of whom had marched with a replica of the Statue of Liberty. According to Shambaugh:

The images presented to the American public tapped into the long-standing American ‘missionary complex ‘to transform China into a liberal society.

Desperate to preserve the security relationship, President George H. W. Bush, who earlier headed the U.S. liaison office in Beijing, argued that ever deeper engagement with China would create the democratic change that the American public and martyred protestors sought. Reading through once-classified documents from that era, preserved in Bush’s presidential library, Shambaugh concludes that “Bush did not hesitate to choose the side of national interests over moral indignation or squeezing the Chinese Communist regime harder so that it might actually collapse or be overthrown,” as was happening in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

The beauty of engagement was its “elasticity,” Shambaugh contends: “The genius of the concept is that it offers different things to different groups and constituencies in the United States — thus offering to everybody a ‘stake’ in the strategy and the relationship.” At a minimum, it meant regular contact between U.S. and Chinese counterparts; at its maximum, it meant influencing China to become more democratic — essentially what Bush promised.

When President Clinton took office, he tried to force democratic change in China by threatening to cut off commercial relations unless China made “overall significant progress” in human rights. This deserves more attention than Shambaugh gives it, as it shows how business had grown powerful enough to block an important presidential initiative. When Clinton’s Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, traveled to Beijing in 1994 to press for change, Chinese Premier Li Peng harangued him for lecturing China on human rights. Li said that U.S. business executives had told him they were lobbying the administration to back off, including officials from General Electric, AT&T and “Gold Sacks,” The Wall Street Journal reported. Clinton dropped the effort shortly afterward.

After that failed attempt, only indirect pressure — the example of American democracy coupled with closer economic and political ties — would be used to try to bring about change in China. Shambaugh recounts Clinton’s answer to a reporter in 1994 who asked if the administration was backing off on human rights. “I believe that the answer to what we should do is to pursue a broader strategy of engagement,” Clinton said. “I think that is likely to produce advances in human rights as well as to support our strategic and economic interests.”

Later in Clinton’s term, China made big changes in economic policy, including privatizing state-owned firms, reducing subsidies and tariffs, to win American support for its bid to join the World Trade Organization. WTO membership in 2001 led to a surge of investment in China, which helped China grow stronger economically but also militarily. Even so, the administration’s 1996 National Security Strategy announced that “a stable, open, prosperous and strong China is important to the United States.”

George W. Bush followed Clinton, initially seeking a tougher line with China and then throwing in fully with engagement. Concerned that Beijing would see him as a knockoff of his father, in the 2000 election campaign Bush Junior dubbed China a “strategic competitor,” in contrast to Clinton’s earlier phrase “strategic partnership.” In his interview with me, Bush’s national security advisor Stephen Hadley commented: “That put the Chinese on notice that they had a skeptical, potential President Bush that they were gonna have to deal with.” Some in Beijing were already wary. Wang Jisi, a leading American watcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, argued in a 1996 article published the Chinese journal Meiguo Yanjiu (美国研究) that engagement was designed, in part, “to constrain China’s global actions within the existing international framework.”

Whatever plans George W. Bush had about pressuring Beijing quickly gave way to seeking its help after the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001. Chinese leader Jiang Zemin also saw the assault as a way to cement relations with the U.S., and telephoned Bush to express his condolences. A month after the attack, Bush landed in Shanghai to confer with Jiang. The trip was meant “to show the world that while the United States was going to deal with the challenge of terrorism, we weren’t going to be preoccupied with terrorism,” Hadley told me. “We were going to continue to play the global role that the United States had traditionally played.”

The U.S. continued to hector China about falling short in its political evolution. In 2005, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick called on China to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the U.S.-led international order — a call seen as paternalistic and insulting to many in Beijing.

Yet continued engagement was never in doubt, as bilateral connections spread far beyond Washington and Beijing. At the time of Zoellick’s comments, U.S. investment in China reached $16.6 billion, quadruple the amount when Bush took office, according to Rhodium Group, a market research firm. About 200,000 Chinese students were studying in U.S. universities, many paying full tuition. A sister city trend had started between St. Louis and Nanjing, Shanghai and San Francisco. American NGOs, foundations and civic organizations had set up operations in China to work on public health, women’s empowerment, forest management, local governance and other topics.

Engagement reached its pinnacle in 2008, when the U.S. financial crisis mutated beyond Wall Street and threatened to collapse the global economy. Twice in the month after Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, President Bush rang Chinese leader Hu Jintao: first to urge him not to sell off China’s $1 trillion-plus portfolio of U.S. debt; and next to recruit him to join a first-ever meeting of the leaders of G20 countries. China joined the U.S. in vastly stimulating its economy by building housing, airports, highways and other infrastructure projects, which consumed billions of dollars of imported goods and helped contain the damage from the financial crisis.

The fall from that pinnacle of engagement was abrupt. Chinese lending led to a burst of production of steel, furniture, concrete, glass and other commodities, which were exported overseas and undermined American factory towns. Chinese officials believed that the crisis revealed the weaknesses of the U.S. economic model, bolstering their determination to follow their own path. China’s America watchers had long predicted the U.S.’s decline, Shambaugh notes: “This time many argued that America’s day as the world’s preeminent power had finally come.”

President Obama took office still needing China’s help in dealing with the financial crisis, so unlike Clinton and Bush he didn’t start by looking to create some distance in U.S.-China relations. But by his second term, relations between the two nations were fraying. In 2011, his administration announced a military “pivot” to Asia, though the U.S. remained mired in wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East. In 2015, Xi Jinping appeared with President Obama in the White House Rose Garden, pledging that he wouldn’t continue to militarize the South China Sea, and that he would curb Chinese cyberespionage of U.S. private companies. He broke both promises. Michael Rogers, then head of the National Security Agency, told me that China restarted its cyberespionage six months after the Rose Garden press conference: “They got quieter. They got better. They seemed to be much more interested in masking or hiding what they were doing.”

By the end of the Obama administration, the U.S. was blocking Chinese bids to buy U.S. semiconductor firms, concerned that it would use them to bolster its military. Not long afterwards, in 2018, Kurt Campbell, an architect of the Obama “pivot,” and Ely Ratner, another Obama alumni, wrote in Foreign Affairs about the failures of engagement: “Neither carrots nor sticks have swayed China as predicted. Diplomatic and commercial engagement have not brought political and economic openness.” We had reached a turning point.

The U.S. continued to hector China about falling short in its political evolution … a call seen as paternalistic and insulting to many in Beijing.

The final break with engagement occurred during the first Trump administration, though Shambaugh misreads what happened. He portrays Donald Trump as an empty suit — a “vessel” through which his hawkish national security team was able to push a much more confrontational approach to China. He lavishes praise on Matt Pottinger, a former journalist who rose to become Deputy National Security Adviser. Shambaugh writes:

Pottinger was instrumental (almost single-handedly) in turning the ‘ship of state’ away from an intrinsic and long-standing ‘cooperate with China’ bureaucratic mission to a ‘compete with China’ bureaucratic mission.

As if that weren’t enough, he adds: “I would venture to say that no single individual — including presidents themselves — have ever had such an impact on the federal bureaucracy as Matt Pottinger did.” Take that, George Marshall, George Kennan and Henry Kissinger.

It’s true that the 2017 National Security Strategy, which Pottinger helped craft, marked the formal end to engagement policy. It labeled China and Russia as “revisionist powers,” contending that contrary to the hope for engagement, “China expanded its power at the expense of the sovereignty of others.” Tough words, to be sure, but at the same time President Trump was pursuing a trade deal with China — the very definition of engagement. During a June 2019 summit with Xi in Osaka, Trump even said the two countries could become “strategic partners,” echoing the language of Bill Clinton during the height of engagement policy.

What finally killed engagement was the Covid pandemic. If historians need a date to mark the break, in my view it is March 16, 2020. That’s when Trump labeled Covid “the China virus” — a moment that Shambaugh simply dismisses as racist (which it also was). Eight years earlier, the two countries worked hand-in-glove to limit the impact of a made-in-America global financial crisis; now they couldn’t even cooperate on a global pandemic that would kill millions of their citizens. “I think 2020 was the watershed,” Pottinger told me. Part of the reason for Trump’s rhetoric on Covid, former Trump State Department official Miles Yu said, is that he and other Trump advisers believed the Chinese knew Covid spread through the air when they sent a delegation to sign the Phase One trade deal in Washington in January 2020, potentially endangering Trump’s life.

After that, Trump released the hawks. Top Trump officials gave a series of blistering speeches attacking China for espionage and influence in the U.S., and Leninist stifling of liberty domestically. They also limited the number of Chinese journalists in the U.S., pressured China to sell TikTok, sent Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar to Taiwan, blocked imports from Xinjiang, and accused China of genocide over repression of Uyghurs.

The break was ratified during the Biden administration, which built on what Trump had done, and tried to recruit allies to constrain China’s military and technological ambitions. Shortly after Biden took office, Secretary of State Antony Blinken offered an elegant formulation of the new policy. China relations would be “competitive when it should be, collaborative where it can be, and adversarial where it must be.” Privately, senior officials were harsher. One said that Biden’s policy was to invest domestically, line up allies and hobble China through sanctions and export controls on advanced technology. After the U.S. and China squabbled over House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in August 2022, and the U.S. shot down a Chinese spy balloon in February 2023, relations were so tense that the two governments were barely talking.

The broader engagement coalition was also fraying. In China, Shambaugh notes, the number of foreign NGOs registered in China shrank from more than 7,000 in 2016 to fewer than 400 in 2018, due to Xi’s repression. In the U.S., the number of Chinese students fell in 2023 to 277,398 students, from its 2019 high of 372,532. U.S. businesses in China also have been feeling pressure. In September 2024, just 47% of respondents to a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai said they were “optimistic” about their five year business outlook, the lowest percentage since the group started taking surveys in 1999.

By the end of the Biden administration, relations had eased somewhat, though neither side expected much improvement. Kurt Campbell, who had declared engagement all but finished in 2018, was now Deputy Secretary of State, responsible for patching up relations. “There’s a recognition that we were overly ambitious about what we thought we could achieve with respect to the trajectory of where China was going,” he told me.

Meanwhile, in China, some America watchers saw the Biden years as confirmation that engagement had ended. Zhang Zhaoxi, a researcher at a think tank affiliated with the Ministry of State Security, called Biden’s China team “liberal hawks” (自由鹰派). In 2022, he wrote in the publication Xiandai Guoji Guanxi (现代国际关系): “[They] emphasize ideological confrontation, stressing the delineation of international camps based on liberal democratic systems and values, and they seek to maintain and consolidate American hegemony through global political and economic systems and rules.”

Breaking the Engagement went to press in December 2024, shortly after Trump was re-elected but before he took office. So Shambaugh does not include Trump 2.0 in his considerations. Instead, he looks at the future of U.S. policy toward China more broadly, recommending a policy of what he calls “competitive coexistence” — essentially a souped-up version of what the Biden administration tried to do.

Shambaugh urges the U.S. government to name a “China czar” in the National Security Council, who would lead the development of an overall China strategy. He recommends that the U.S. invest heavily in science and technology at home, work closely with allies in dealing with China, and sharply increase support for information services to counter Chinese propaganda. All are reasonable suggestions, although they now seem almost quaint given the go-it-alone approach of the second Trump administration, which has slashed spending science, hit allies with heavy tariffs, defenestrated the National Security Council, and is dismantling Radio Free Asia and other government news and information programs.

The direction that Trump will take from here is uncertain. Last Friday he called Xi Jinping, discussing the future of TikTok among other issues. He has also pushed for a meeting with Xi in Beijing, where the Chinese are sure to replicate what they did in 2017, when they wowed him with dinner in the Forbidden City. Already, he has eased some export controls on semiconductor sales to China that the Biden administration put in place, and has reportedly held up arms sales to Taiwan to avoid riling Xi before a possible meeting. Trump has long been less concerned about Taiwan’s fate than other presidents; Beijing will surely look for concessions to get him to agree to reduce support for Taiwan’s security.

Trump’s go-to move is deal-making, which is another form of engagement. He will do his best to make a deal whenever he and Xi get together. His agreements with other trading partners suggest the general direction he will take: reducing tariffs on China in exchange for Chinese investment and purchases of U.S. goods, among other side deals such as pushing for a crackdown on exports of fentanyl precursors. Fundamentally, Trump has shown himself to be drawn towards — or at least admire — authoritarian, strongman governments. That suggests he will want to remain in conversation with China, not just work against it.

Engagement may seem dead, but its story isn’t over. As Shambaugh documents, U.S.-China relations have ping-ponged over the centuries. The first Trump administration sought to kill engagement; the second may seek a revival. ∎

- Correction (9/25/25): The original version gave the location of the potential assassination attempt as Fudan University in Shanghai, and the students as being bussed out instead of put on a train. ↩︎

For more on this topic, read Bob Davis’ series of interviews at The Wire China with figures instrumental in shaping U.S.-China relations, and David Barboza’s own Q&A with Davis about the resulting e-book.

Bob Davis covered U.S.-China relations for The Wall Street Journal from the start of the Clinton administration to the end of the first Trump administration. He is co-author of Superpower Showdown (2020), a history of Trump’s trade war with China, and author of Broken Engagement (2025), an anthology of interviews conducted for The Wire China.