Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Register now to hear Patrick McGee talk about Apple in China at Asia Society tomorrow, Oct 22, at a China Books Review event moderated by Wired senior writer Zeyi Yang.

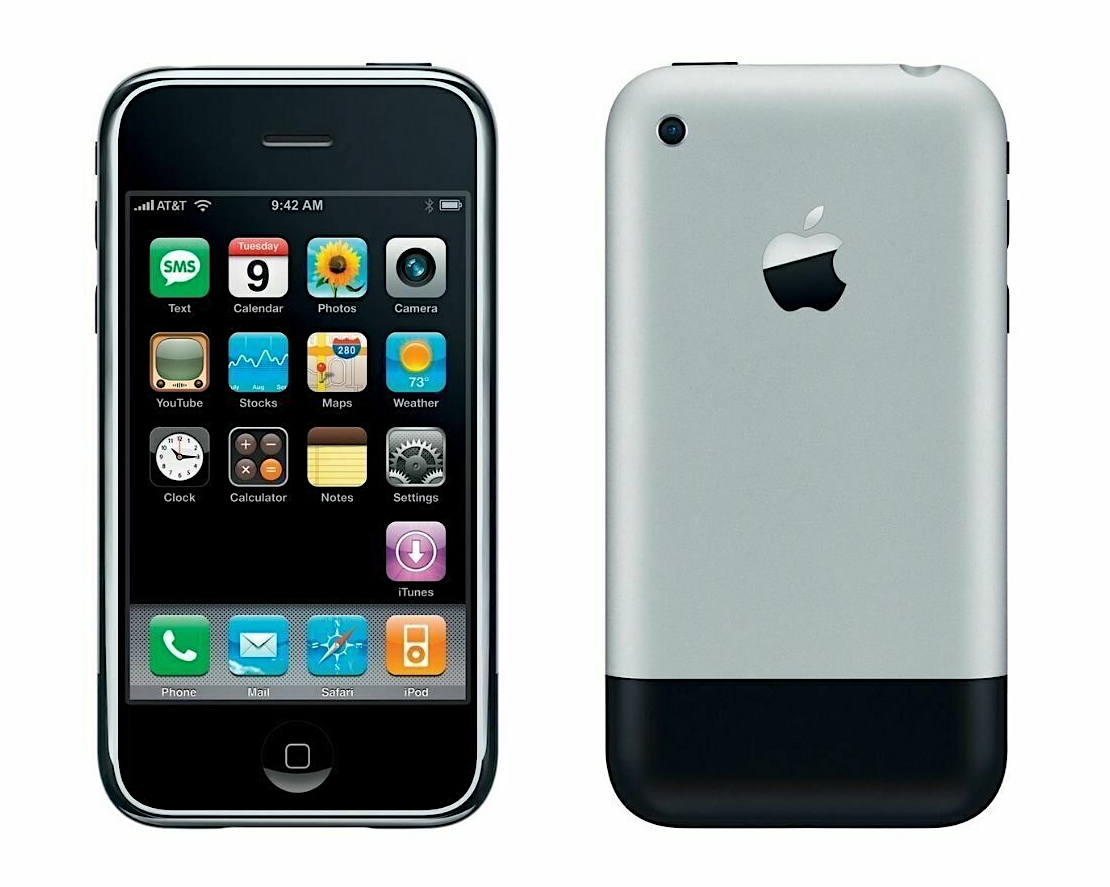

On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs stood before a packed auditorium, once again in a black turtleneck and blue jeans. “Every once in a while,” he said, “a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.” Then he introduced it — the iPhone — to an audience mesmerized by full-screen web navigation and the basics of multi-touch, like pinch to zoom and swipe to unlock, or the way the screen would bounce to indicate a page couldn’t scroll any further. The prototype had experienced all kinds of software glitches in the days before, instilling feelings of anxiety and terror into a small group watching within the auditorium. “There we were in the fifth row or something — engineers, managers, all of us — doing shots of Scotch after every segment of the demo,” a radio engineer named Andy Grignon once recounted. “After each piece of the demo, the person who was responsible for that portion did a shot. When the finale came — and it worked along with everything before it, we all just drained the flask. It was the best demo any of us had ever seen.” The presentation was so good that some executives at BlackBerry maker Research in Motion thought it was faked somehow.

Two weeks after unveiling “the one device,” Steve Jobs walked into a routine divisional meeting. He was in a bad mood and didn’t look good. Then he pulled out his prototype iPhone, which looked worse. The keys in his pocket had cut a huge gouge across its plastic screen. He threw the unit onto the boardroom table toward Steve Zadesky and demanded: “Make it glass.” It wasn’t the first time the idea had come up. In September 2006, just four months earlier, Jobs had grown angry about smaller scratch marks and complained to a mid-level executive: “Look at this, look at this — what’s with the screen?” The executive responded, “Well, Steve, we have a glass prototype, but it fails the one-meter drop test one hundred times out of one hundred times.” Jobs cut the executive off. “I just want to know if you’re going to make the fucking thing work.” Now, in January, Jobs wasn’t taking excuses. Apple had just announced the phone would be available in June; the date couldn’t be pushed back. Six months would’ve been a rush job; but they had even less time than that. The display is a module that had to be ready months ahead of the assembly.

What followed is perhaps the best-known anecdote on the manufacturing of the original iPhone. Jobs reached out to Wendell Weeks, CEO of Corning, a glassmaker in upstate New York, saying he needed the hardest glass they could make. Weeks told Jobs about Gorilla Glass, something Corning had developed for fighter-jet cockpits back in the 1960s. They’d never found a market for it and abandoned the project. Jobs convinced him to begin production immediately.

The decision risked throwing Zadesky, who managed all the mechanical parts for the iPhone project, into a tailspin. He and Tang Tan, another iPod veteran, had to quickly put together a touchscreen supply chain, as glass and plastic function in totally different ways. Senior Vice President Tony Fadell likens this “crazy” phase to landing “a fleet of 200 jets on an aircraft carrier, all within minutes of each other. And all the jets were running out of fuel.” Apple needed to find manufacturers that were highly competent, but with enough capacity to free up their top talent.

Among the suppliers it found was Lens Technology, a glass specialist Apple worked with to cut and place Gorilla Glass. It was founded by Zhou Qunfei, who dropped out of high school at age sixteen and left her impoverished village to work in the factories of Shenzhen. She found a job making watch lenses, earning about a dollar a day polishing glass. She hated the work but was eager to learn, and her boss offered her the chance to understand the science behind the manufacturing. Zhou — “Jane” to Apple engineers — eventually saved up $3,000, started her own company in 1993, and 11 years later was making small glass screens for Motorola with a team of 1,000 people. Apple engineers grew to have great respect for her operational skill and ability to leverage help through political channels. The company’s main factory was in Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province where Mao was born. One engineer working in the factory recalls a time when power went out across the district. Lens couldn’t operate. But Zhou was so well connected that, in a short period of time, multiple fire trucks showed up. Each carried generators, and soon Lens was back to tempering and precision shaping glass — the only factory up and running for multiple blocks.

Another important supplier was TPK, which placed a special coating on the Corning glass, enabling the user’s fingers to transmit electrical signals. The Taiwanese start-up had been founded just a few years earlier by Michael Chiang, an entrepreneur who in the PC era had reportedly made $30 million sourcing monitors and then lost it all on one strategic mistake. In 1997 he began working with resistive touch panels used by point-of-sale registers. When Palm was shipping PDAs that worked with a stylus, Chiang worked on improving the technology to enable finger-based touchscreens, even showing the technology to Nokia. But nobody was interested until 2004, when a glass supplier introduced TPK to Apple. An iPhone engineer calls Chiang “a classic Taiwanese cowboy [who] committed to moving heaven and earth” by turning fields into factories that could build touchscreens. The factory was in Xiamen, a coastal city directly across from Taiwan. “The first iPhones 100% would not have shipped without that vendor,” this person says. He recalls Chiang responding to Apple by saying, “‘We can totally do that!’ — even though [what we were asking was something] nobody in the world had ever done before.”

Among the techniques Apple codeveloped with suppliers was a way to pattern, or etch, two sides of a piece of glass to do the touch sensor, at a time when film lithography processes were being done on only one side. Another pioneering technique is called rigid-to-rigid lamination, a process for bonding two materials using heat and pressure, which Apple applied to tape a stack of LCD displays to touch sensors and cover elements to create one material. The process was performed in a clean-room environment with custom robotics.

Apple was secretive about each of these cutting-edge methods. One result of this is that outsiders failed to grasp the advancements taking place in China for the iPhone. In the Western press it was common to misrepresent China’s role as being all about low-value assembly. These studies were based on opening an iPhone and breaking down where the display, chips, and other components came from. As most expensive parts were typically from Korea, Japan, and the United States, those doing the assessing would conclude that China’s contributions were de minimis. “China [just] happens to be the last stop in a given product’s long global supply chain,” wrote the president of the Export-Import Bank of the United States. “The Chinese make products like the iPhone possible without reaping much of the benefits.” Similarly, at one point, two scholars deduced that the work performed by Chinese workers contributed just 3.6% to the $179 wholesale cost of an iPhone. When The Wall Street Journal picked up on the study, it headlined the article: “Not Really ‘Made in China.’”

The analyses were wrong. Apple was making spectacular investments in China; it’s just that the contributions weren’t found within the iPhone, but in the machinery and processes that made it. “Sure, the glass comes from Corning, but does it come in that shape?” says one manufacturing design engineer, referring to the U.S.-made glass on the iPhone. “Corning glass is useless until Lens makes it useful.” As for wages, observers were often counting only the steps in final assembly, oblivious to all the labor that went into building the components. Even so, it’s true that Chinese wages per iPhone were a small percentage of the wholesale cost; however, this wasn’t reflective of their insignificance but, counterintuitively, a sign of the China-based factories’ importance. The low cost per unit reflected their efficiency.

Only after all this complexity making the touchscreen glass with cutting-edge processes did the tedious monotony of actually assembling the iPhone begin over at Foxconn’s Shenzhen factories. As The New York Times would famously recount later, once Apple worked out how to make the glass screens, a foreman roused 8,000 workers inside the Foxconn dormitories, gave each employee “a biscuit and a cup of tea, guided [them] to a workstation and within half an hour [they] started a 12-hour shift fitting glass screens into beveled frames. Within 96 hours, the plant was producing over 10,000 iPhones a day.”

Apple was secretive about its cutting-edge methods. Outsiders failed to grasp the advancements taking place in China for the iPhone.

In 1999, the Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Foxconn was a company with $1.8 billion of revenue, far smaller than Solectron, SCI, or Flextronics, its U.S. rivals. By 2010, Foxconn revenues were $98 billion, more than those of its five biggest competitors combined. And Foxconn’s extraordinary growth in those eleven years is the consequence of one client more than any other: Apple.

The Apple-Foxconn relationship goes back to at least the early 1990s, but in a limited way. Foxconn had been championed by H. L. Cheung, a Singaporean Apple executive from 1981 to 1997, who would later join Foxconn. But Terry Gou’s company was mostly just a supplier of affordable components, like those connecting printed circuit boards to the housing. Apple engineers from the mid-1990s remember it as “the connector company.” But Foxconn quickly expanded its skill set, and approaching the year 2000, it was demonstrating its prowess as a jack-of-all-trades with a model different from the other Taiwanese companies expanding to the mainland.

Foxconn began offering final assembly on the cheap for the same reason Costco sells hot dogs: It gets people in the door. Foxconn then upended the world of tooling by giving it away for free. That is, Gou would offer to pay the up-front costs of establishing the custom molds, dies, fixtures and other equipment necessary to start building a product at scale. “That can be half a million or a million dollars,” says a former Apple engineer. “And that was absorbed by the manufacturer — by Foxconn. So Apple just paid for the production parts.” Then Foxconn would work to integrate all procurement, manufacturing and logistics into a one-stop shop. It made its money back the same way a mobile carrier might — giving customers a free phone but earning fees in a two-year contract. This Apple engineer describes Gou’s approach as a wily bet to lure in Western companies, getting them hooked on the drug of cheap production, and creating a sticky relationship based on Foxconn’s choice of components. “Once they get you in the door, that’s it — they control you,” he says. “Foxconn isn’t called ‘Fox-con’ for nothing. Terry Gou was a gambler, and the real name of the company is Hon Hai. That was changed to Foxconn because he’s a fox, and he’s a con artist.”

Terry Gou’s perseverance had won Foxconn the exclusive contract to build the iPhone, but his strategy to make Apple dependent on his operations — so he could squeeze out more profit — failed spectacularly. Instead, Apple squeezed Foxconn, leveraging higher volumes to attain lower costs while obstructing Foxconn’s efforts to choose which sub-suppliers to work with. In 2000, the first year Foxconn performed major operations for Apple, it had reported net margins of 10.6%. As it got more work with Apple, revenues soared while margins plummeted — to 4.6 percent in 2007 and then to 2.4% in 2011. So while Foxconn revenues more than doubled — from $53 billion in 2007 to $107 billion in 2011 — profits merely inched up from $2.41 billion to $2.53 billion. “It was just brutal the way we’d work with suppliers,” a former Apple VP says. “We wanted something, and we just got it. And they just wanted our business. It was incredible … The red carpet was rolled out everywhere we went.”

For the original iPhone, Foxconn had even agreed to a no-quibble warranty, an onerous clause known internally as “a Tony Blevins special,” after Apple’s procurement specialist with a reputation for negotiating absurdly good deals across the supply chain. The clause compelled Foxconn to take full responsibility for any iPhone failures within the first twelve months after purchase. “The no-quibble warranty meant that if we get a return, we’re sending it back to you, and you fix it and deal with it,” another person says. The clause was an incentive for Foxconn to maintain high quality standards — no funny business like saving on costs by using unauthorized suppliers, the sort of trick contract manufacturers were infamous for.

Blevins had already been a spectacular negotiator, and as Apple grew, he developed further ways to tilt the field. He’d organize suppliers into adjacent hotel rooms, then travel from one to the next, pushing prices lower and subtly indicating that some rival had just made a better offer. Blevins wouldn’t let the suppliers order food or leave the rooms, and depending on the situation, he’d toy with the temperature. If it was the kind of hot and humid summer in Hong Kong when nobody would think to have brought a jacket, Blevins would crank up the air-conditioning in the hotel room, to the point where only the Apple team was appropriately dressed. “Then they would go all night till they made them cave,” one colleague says. It was always hard to say no to Apple, and Blevins knew it. In the 2010s, Apple would often ramp a product from hundreds of thousands of units to the tens of millions. Margins might be risibly low, but a supplier could become rich off the volumes.

The no-quibble terms were a legacy of the iPod, a relatively simple product and one for which Foxconn was directly sourcing many of the parts. Apple had taken control of the more strategic and high-value-added items, but Foxconn had sourced commodity components on its own. Lacking any data on the iPhone before it was released, Foxconn treated it like an iPod and agreed to the same terms. But consenting to the same clause for such a different product proved to be a disaster. For the first iPhone, the percentage of units that came back within twelve months — what Apple calls TWR, standing for total warranty repair — was around one in seven. There were problems with the home button and the volume controls, and a spate of issues that didn’t meet standards from the perspective of field durability.

Foxconn wasn’t necessarily building it poorly; it was simply the first consumer electronics product of that complexity to be used multiple hours a day. Apple’s quality standards were high, but they weren’t built to meet smartphone addiction — a concept that hadn’t really existed before. “You use an iPod occasionally, but you use the iPhone all the fucking time,” says an executive involved in manufacturing the original unit. The no-quibble clause was maintained for at least two to three generations of iPhone, until it got to a point where Foxconn was losing money and they had to plead with Cupertino to amend the contract. “It became untenable from a business standpoint,” says a person familiar with the change. That Foxconn would even sign such a contract demonstrated their willingness to do anything to work with Apple. Their hunger got to the point of being irrational — and Apple would fully exploit the situation.

Foxconn began offering final assembly on the cheap for the same reason Costco sells hot dogs: It gets people in the door.

When the iPhone went on sale in July 2007, some higher-ranking executives were given theirs two days before launch. One made the mistake of using it in public at the Berkeley Greek Theatre. “When a few people recognized what I had in my hand, I nearly got mugged and raped,” he says. His crude language is imprecise but meaningful — it connotes the animalistic lust people felt. Like many at Apple, this executive hadn’t grasped the intensity of consumer excitement. When dozens of people camped out in front of the Apple Store for multiple days, employees didn’t know if they should applaud their enthusiasm or kick them off the premises.

The hype was just enormous, as though people really did grasp what a cultural icon the iPhone was going to be. But even competitors that had a precise sense of the magnitude of Apple’s achievement failed to understand the company’s lesser-known advantages — its operational superiority and its newfound edge in eliminating defects. Quietly and without any fanfare, Apple had been building a yawning gap over the competition, improving hardware each year at a greater scale than the last. As Microsoft, Nokia, BlackBerry and every other phone maker scrambled to respond, they found themselves fighting yesterday’s war. They’d compete with the original iPhone, only to be outgunned by the following year’s 3G model, which doubled the speed, halved the price, and was enhanced by an App Store fed by thousands of software developers worldwide.

The iPhone was such a watershed device that success in the decade following its launch was determined by how brazenly competitors copied it. All attempts to do something different failed. Within just six or seven years, Nokia was nearly bankrupt, BlackBerry was close to dead, and Microsoft’s smartphone ambitions had been rendered irrelevant. But the cause of their demise wasn’t solely Apple, whose global market share in the 2010s wouldn’t exceed 18%. Rather, they were killed in two stages. First, by the likes of Taiwan’s HTC and South Korea’s Samsung, whose use of open-source Android software from Google enabled them to rival the best features of the iPhone. And then by new Chinese rivals, which were aided by the education in hardware excellence they’d all received from being part of Apple’s China-based, world-leading supply chain.

As Apple grew its operations, more engineers were worrying about its dependence on China, which didn’t appear to be opening to the world as they believed it would. Some shared stories of what they called “OIC events” — experiences that would occur only in China. One engineer recalls getting ready in the morning at a hotel in Shenzhen and glancing at the international news playing silently on his TV as he spoke with his wife back home in California. “The Dalai Lama came on,” he recounts. “And I said to my wife, ‘That’s weird, the Dalai Lama is . . . ’” Then the TV screen went blank. China’s censors had cut the feed within seconds. Years later, he’d remember the incident as a foreboding sign. ∎

Adapted from Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company by Patrick McGee. Copyright © 2025 by Patrick McGee. Excerpted with permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Header: A Chinese national flag at the Apple Store in Chongqing’s Jiefangbei Central Business District, October 2025. (Cheng Xin/Getty)

Patrick McGee is a technology writer and the author of Apple in China (2025). He has been a journalist with The Financial Times since 2013, reporting from Hong Kong, Frankfurt and California. McGee holds a BA in religion from the University of Toronto and a graduate degree in global diplomacy from SOAS, the University of London.