Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: The Chinese Tragedy of King Lear by Nan Z. Da (Princeton University Press, June 2025).

Also watch Nan Z. Da’s book talk about Shakespeare and tyranny, with Stephen Greenblatt, hosted by China Books Review at Asia Society last month.

“The tragedy of Maoist and post-Maoist China and Shakespeare’s Tragedy of King Lear are uncannily similar,” announces Nan Z. Da at the beginning of her idiosyncratic but wonderfully original book The Chinese Tragedy of King Lear. She continues:

The most ‘Chinese’ of Shakespeare’s plays, Lear’s comparability to China goes beyond themes of filial piety, ingratitude, scalar disharmony, and merit-blind retribution. The two also share a logic of gaslighting, a pain rooted in real withholding, and other crimes and cruelties that come from the empty forms that pop up when the personal totally collapses into the political.

Born in Hangzhou, China, Da now teaches literature at Johns Hopkins University. She turned to King Lear in part to help her make sense out of the tragedy that befell her own family and birthplace during China’s communist and cultural revolutions. What impels her exploration is a recognition that the imbroglio King Lear brings down on his family and kingdom shares a symmetry with the revolutionary holocaust that Chairman Mao visited on his people. Both cataclysms were generated by the perverse human impulse to abuse, and Da sees Lear as illustrating what happens when the keystone of any human arch — a family, country or global order — fails. As “disfigurement leads to further disfigurement,” a cascade of malefactions and cruelties follow.

“Some parents and states are, of course, truly abusive,” she writes, equating the damage done to children by abusive parents with the far larger scale of damage done by abusive leaders to their subjects. “Parental tyranny leads to childish tyranny leads to state tyranny leads to parental tyranny,” she warns. Once such a spiral develops, it is hard to arrest:

Let’s say that your parent, your state, your sovereign, is being abusive. They falsely accuse you or others of inane offenses, or they force you to accept foolish and illogical plans. They ask you to accept wrong as right, to pretend to love when you really do love.

Da suggests that when wounds become too deep, fundamental human operating systems become so corrupted that immediate remedy, even if effected by well-intentioned leaders, can prove no more than epiphenomenal. “Can history recover from betrayals between families and children?” she asks — and, she infers, between tyrants and citizens?

I vividly remember when, two years after Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping unexpectedly reappeared to try and transform China under a bold agenda of “reform and opening” (改革开放). Alas, it did not prove that easy. Mao’s word had been made flesh, and the toxin of his revolution had become so infused into the bloodstream of the Chinese people that — as is demonstrated by Xi Jinping’s latter day Maoist reign — the past is not so easily expunged.

In the Confucian scheme of things, the family is a microcosm of the state’s hierarchical filial order. Da emphasizes how disorder in one realm not only infects the other, but cascades through future generations. The result is that an acceptance of abusive behavior that allows no remonstration becomes almost autonomic, and responses such as sycophancy become the currency of politics. Such are the consequences, she suggests, of the “kind of state [that] does not trust its own people to know what is in its heart” and embraces “those who will say only flattering things,” much like Lear’s daughters Goneril and Regan — a syndrome that is equally emblematic of China’s state-society relationship.

Da is drawn to Shakespeare because she sees plays such as King Lear as holding the key to a psychological understanding of the historical tragedy of China that her own family suffered. After coming to the U.S. in 1992 and studying Western literature in grade school and university, she began to see that China’s tragedy was not unique, except in scale. (Some 30-40 million perished in the Great Leap Forward, before the ruinous Cultural Revolution even began.) The magnitude and severity of this self-inflicted catastrophe left hundreds of millions more struggling to explain how such an apocalypse could have happened, and how they might begin to manage the physical and emotional consequences.

Corroboration from another cultural tradition helps Da to affirm that tyranny is tyranny, no matter when or where it takes place.

China had never developed an explicit theoretical construct or psychological framework for understanding human motivation, as Western writers including Sophocles and Euripides had when, more than two millennia ago, they explored what the Greeks referred to as the human “psyche.” This exploration took an evolutionary leap forward in Europe with the advent of Christianity and its emphasis on an individual soul, or spirit, capable of connecting directly to God without mediation from outside authority. Shakespeare was influenced by both, before the study of psychology crescendo-ed with the analytical works of Sigmund Freud and Karl Jung as they sought to understand, and treat, the complex psychological syndromes to which human life inevitably gives birth.

As part of this lineage of exploration, Nan Z. Da repurposes King Lear as a western literary mirror she can hold up to China in order to better understand how such tragedy happened there. For her, the play is something of a Rosetta stone, revealing the universal nature of hamartia, the tragic flaws that can cause entire families or kingdoms to collapse. Corroboration from another cultural tradition helps Da to affirm that tyranny is tyranny, no matter when or where it takes place. Ambition, paranoia and distrust, she finds, are human imperfections that, when excited by fears of appearing weak, often lead to an excess of ambition, or hubris. And as we know from Greek tragedy, hubris leads to tragic consequences, just as it did in Mao’s China.

“Will the world appreciate what has happened to the Chinese people, its intensity, its scale?” asks Da. She wonders “what can be set right … and what cannot.” The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not about to make a meaningful mea culpa that might facilitate a reconciliation with its past and begin to set things right. In its view, any admissions of Party wrongdoing would only undermine its pretension as the selfless and infallible “liberator” of China from imperialism, feudalism and capitalism. And the Party can never be anything but “correct.” The irony is that all the misery Mao’s revolution wrought was done in the name of “correctness,” to build a new and more humane socialist idyll. But, as Lear’s daughter Cordelia bemoans of her family’s fall, “We are not the first who with the best meaning incurred the worst.”

When their dreams crash and burn, revolutionary idealists have too often been unable to acknowledge failure and seek course correction. Instead, pride has compelled mendacity and violence in the hope that the realization of their dream lies just around the corner, and only needs an extra organizational boost. This is the rationalization of Leninism as much as Learism. Alas, at such times, anyone like Cordelia — who refuses to propitiate power and instead speaks honestly when asked by Lear to emptily affirm her love for him at the start of the play — is tarred as a dissident.

“Citizens of authoritarian regimes might accordingly identify with Cordelia’s position,” writes Da. For she “has denied the tyrant his preferred mode of interaction: a show of love unmarred by dissent, and acceptance of unreason without any balking.”

Like most vain sovereigns, what Lear seeks, even from his daughters, are expressions of devotion and loyalty, whether heartfelt or not. Cordelia is incapable of doing this not because she does not love her father, but because by nature she cannot perform disingenuously on command, unlike sisters Goneril and Regan. For this lese majeste she becomes a filial dissident. As Edgar proclaims at the play’s tragic end, “Speak what you feel, not what you ought to say.” Yet because Cordelia does precisely that, like so many brave Chinese dissidents who have refused to pander to their leaders, she and they are viewed as apostates.

In Lear’s eyes, Cordelia has rebuked him. So he responds to her truthfulness with umbrage and vindictiveness — a response with which countless Chinese dissidents who encountered similarly retributive reactions from the Party, such as Liu Xiaobo who died in prison after daring to speak truth to power, were all too familiar. A world where candor brings punishment and falsity advancement, writes Da, is a world where “Every circle of relations, from the personal to the cosmic, has been disordered.”

Even the cosmology of Lear and that of traditional China have a cruel symmetry here. In both, deranged human relations beget an expanding circumference of disorder that Shakespeare emphasizes with atmospheric equivocation. As crazed Lear roams the heath in Act III, having been cast out by his other two venal daughters, the physical environment is beset by raging storms, mirroring his inner state of derangement with a roiled outer world. So too, in Chinese cosmology, an emperor’s right to rule was believed to derive from “the will of heaven” (天命), a cosmic sanction conferred on upright rulers. Heaven was said to manifest its displeasure with emperors who lacked uprightness through disorder and disharmony, heralded by natural phenomena like storms, earthquakes, draughts and floods. Indeed, some thought that the Tangshan earthquake in July 1976, months before Mao’s death, heralded heaven’s displeasure with his tumultuous rule. As the ancient expression goes, “Natural calamities follow the wrong doings of men” (天灾人祸).

By using King Lear to illuminate modern China’s tragic fall into upheaval and tyranny under Mao, Da reminds us why Shakespeare’s plays still have worth. In ways that discussions of policy cannot, they help us make sense out of human motivation.

Lear responds to Cordelia’s truthfulness with umbrage and vindictiveness — a response with which countless Chinese dissidents who encountered similarly retributive reactions from the Party were all too familiar.

Those born in the wake of WWII — the last heyday of “big leader kultur” and Lear-like “tragic heroes” — may be forgiven for wondering how, after ridding ourselves of Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini and Mao, we find the global stage again littered with a growing cast of nouvelle tyrants? These are not just tin-pot dictators ruling Latin American banana republics or post-colonial African satrapies, but despots with titanic egos and insatiable territorial ambitions. At the top of this pyramid sits the unholy trinity of Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. Waiting in the wings for their turn on the big stage is a junior league of understudies including Alexander Lukashenko, Kim Jong Un and Victor Orban.

This new proliferation of larger-than-life autocrats raises many questions: Why are they now re-appearing? How did they come to power? Is there a democratic antidote for their tyranny? And, if left undeterred, where will they take us? To answer such questions, it can sometimes be helpful to turn to literature rather than just history and politics. After all, since the 5th century bce, when Sophocles and Euripides began divining the psyches of “big leaders” in their tragedies, human beings have changed little. Yet modern policy wonks have come up with few new insights into how to understand such men, who now aspire to rule the world like Zeus on Mt. Olympus.

While teaching King Lear, however, Nan Z. Da began to see an archetype: A class of unrestrained leader who, upon losing the capacity to distinguish between loyalty and sycophancy or truthfulness and mendacity, also lose the ability to rule humanely and effectively. Next, she wondered how people’s formative years can so psychologically damage them — whether through parental abuse, poverty, war or revolution — allowing a gnawing sense of inadequacy to give rise to overblown dreams of grandeur and imperial greatness. Never mind that it is clear that no amount of wealth or power can slake their abiding sense of insufficiency. She writes:

What happened in China in the long twentieth century to millions, then to more than a billion people, resembled Lear’s imagined and actual worlds: a plague, a regime change, political paranoia, persecutions that were religious and theatrical in nature.

When it comes to tyranny, a country’s unique national culture or history does play a role. But in the universal archetype of Lear, ambition and blindness transcend culture, language, religion, political system and even economic prowess. It remains to be seen how China’s impressive economic development will stand up to its revitalized autocracy. But, as the U.S. is now beginning to discover, much greatness can be undone by a leader who is insecure, mercurial and left unrestrained.

Da is not the first literary scholar to have used Shakespeare as a way to understand the world of real politics. In his 2018 book Tyrant, Harvard’s Stephen Greenblatt discusses the protagonists of not only King Lear but other plays such as Richard III, Hamlet, Macbeth and Coriolanus. He writes:

From the early 1590s, at the beginning of his career, all the way through to its end, Shakespeare grappled again and again with a deeply unsettling question: How is it possible for a whole country to fall into the hands of a tyrant? … Why do large numbers of people knowingly accept being lied to [and are] drawn to a leader manifestly unsuited to govern, someone dangerously impulsive or viciously conniving or indifferent to the truth? Why, in some circumstances, does evidence of mendacity, crudeness, or cruelty serve not as a fatal disadvantage but as an allure, attracting ardent followers? Why do otherwise proud and self-respecting people submit to the sheer effrontery of a tyrant?

Greenblatt is drawn to Shakespeare because “his plays probe the psychological mechanisms that lead a nation to abandon its ideals and even its self-interest,” turning it into a country of collaborators. After all, he reminds us, “such a disaster, Shakespeare suggested, could not happen without widespread complicity.”

Like Da, Greenblatt believes Shakespeare can help us understand “the ways in which a society becomes ripe for a despot.” One of the hallmarks of such ripeness is a “strong current of contempt for the masses and for democracy as a viable political possibility,” except when a tyrant “sees that they can be made to further his ambitions.” As overweening hubris gets acted out, a kingdom, nation or democracy is thrown into chaos.

However, it must be said that in terms of abusive tyrants, there are more egregious examples than Lear. He is less of a big-time tyrant, more of a lonely old man beseeching his daughters for an expression of his importance. Because Shakespeare explores such subjective frailties, Lear proves relevant to Nan Z. Da as a portal into the psychology of human interaction, whether between kings and fathers or children and citizens, as much as into modern Chinese history. Lear registers far lower on the Richter scale of tyranny than Mao, and of those who have ascended the dragon throne since, but the dynamics are familiar.

After ridding ourselves of Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini and Mao, we find the global stage again littered with a growing cast of nouvelle tyrants.

There are perhaps better examples of tyranny in Shakespeare’s other works. York in Henry VI, for example, proclaims, “I will stir up in England some black storm,” eerily evoking Mao’s own urge to “overturn” (翻身) China and make “great disorder under heaven” (大闹天宫), an impulse that most likely took root in his fraught early years. In a 1936 interview with Edgar Snow, Mao recounted how he’d been repeatedly beaten by his tyrannical father. “I learned to hate him,” Mao confided. “I learned that when I defended my rights, my father relented, but when I remained weak and submissive, he only cursed and beat me the more.” The bedlam that Mao subsequently unleashed on China led the scholar Lucien Pye, in Mao Tse-tung (1976), to conclude that he had “learned the spirit and tactics of rebellion” as a boy.

For an explication of true tyranny, the more telling play is Richard III, where Shakespeare more explicitly limns how a warped leader, drunk on power, can bring disaster down not only on individuals and families, but countries and even the world. Here, Greenblatt’s work adds an important dimension to Da’s exploration of the inner nature of autocracy. What characterizes real tyrants, says Greenblatt, is their “limitless self-regard, the lawbreaking, the pleasure in inflicting pain, the compulsive desire to dominate.” Such a man — and they are almost always men — is “pathologically narcissistic, and supremely arrogant.” Greenblatt continues:

He has a gross sense of entitlement, never doubting that he can do whatever he chooses. He loves to bark orders and to watch underlings scurrying to carry them out. He expects absolute loyalty, but is incapable of gratitude. The feelings of others mean nothing to him. He has no natural grace, no sense of shared humanity, no decency. … [He] divides the world into winners and losers. The winners arouse his regard in so far as he can use them for his own ends; the losers arouse only his scorn. The public good is something only losers like to talk about. What he likes to talk about is winning.

Then there is Richard’s hump. “It is as if the universe had marked him outwardly to signify his inner condition,” writes Greenblatt, as “a kind of preternatural portent or emblem of his viciousness.” Greenblatt postulates that Shakespeare is showing how a child unloved by his parents and “forced to regard himself as a monster will develop certain compensatory psychological strategies, some of them both destructive and self-destructive.” Richard “dies unloved and unlamented,” with even his mother shunning him. Yet, he adds:

One of the tyrant’s most characteristic qualities is the ability to force his way into the minds of those around him, whether they wish him there or not. … No one can keep him out.

Here, Americans may find a haunting echo of the world in which they now find themselves unexpectedly plunged — one in which, as Greenblatt writes of Richard III, “there are almost no morally uncompromised lives.” Nobody can even bring themselves to believe that tyranny is approaching; as Buckingham observes, they “spake not a word, but like dumb statues or breathing stones, stared at each other, and looked deadly pale.” Just so, when I was in Mao’s China during the Cultural Revolution, leaders fell in line or mysteriously disappeared, and ordinary people mouthed the proper Mao slogans. There was not a scintilla of evidence in daily life of dissent or discord with the prevailing ideology.

In King Lear the damage is done by missteps instead of malicious cruelty. The tragic end of the play, however, is brutal — leaving Nan Z. Da to wonder how such abuse can ever be undone. What if “the disposition from which his first error sprang is still unchanged?” as she quotes the scholar A.C. Bradley in Shakespearean Tragedy (2005). Then, she raises a disheartening prospect: “Even if Maoist totalitarianism can be repeated with variations, we assume we are safe in the knowledge that at least its saddest victims — the best people who were harmed — would not be among the first to clamor for its revival. … Lear throws that into question.”

Why? Da plaintively observes: “Younger generations who learned of these atrocities from their parents and inherited from them a basic skepticism about the nation-state often found those same parents going back to defend and even champion ultranationalism, Mao, and now Xi’s regime.” So, she warns of the consequences for nations that become beholden to “a monarch whose personal pathologies become the state’s.” Because Mao’s revolution affected several generations, she believes his pathologies may have become so deeply rooted that it could be generations more before they can be extirpated. This is what makes both play and reality truly tragic: Too often a country, society or family becomes trapped in spirals of abuse and disorder.

Ultimately, Shakespeare reminds us that even the most powerful and wealthy monarchs, emperors, führers, presidents or general secretaries are still human beings filled with insecurity, pride, vanity and ambition, capable of bringing ruin even to the greatest of empires. It turns out that such traits are as true of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and other neophyte tyrants of the 21st century as they are of Shakespeare’s villains. This is the lesson that both literature and history teach, should anyone choose to heed it.

In an on-stage conversation, I asked Nan Z. Da how, after writing The Chinese Tragedy of King Lear, she saw China’s future. After insisting that she was an optimist at heart, she added a caveat, quoting the Chinese author Nien Cheng: “As long as Mao’s portrait hangs in Tiananmen Square, China is forever cursed.” ∎

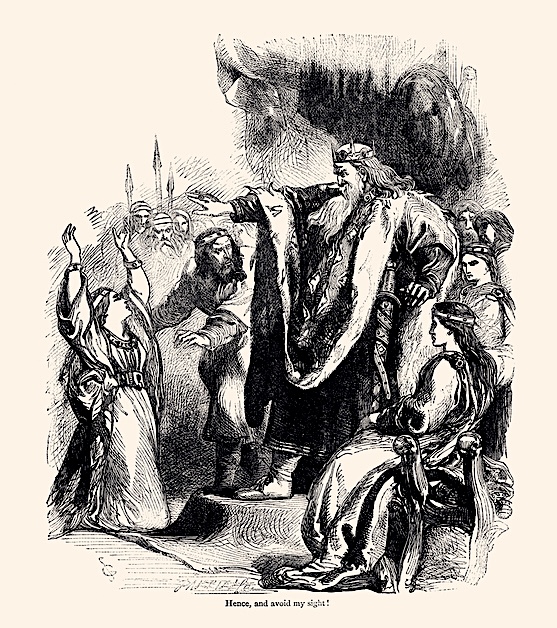

Header: An 1838 wood engraving of the storm scene in King Lear (Act III, Scene IV) based on a painting by Benjamin West. (Getty)

Orville Schell is the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society, and co-publisher of the China Books Review. He is a former Professor and Dean at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of over ten books about China. He is a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, Foreign Affairs and other publications, and has traveled widely in China since the 1970s.