Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

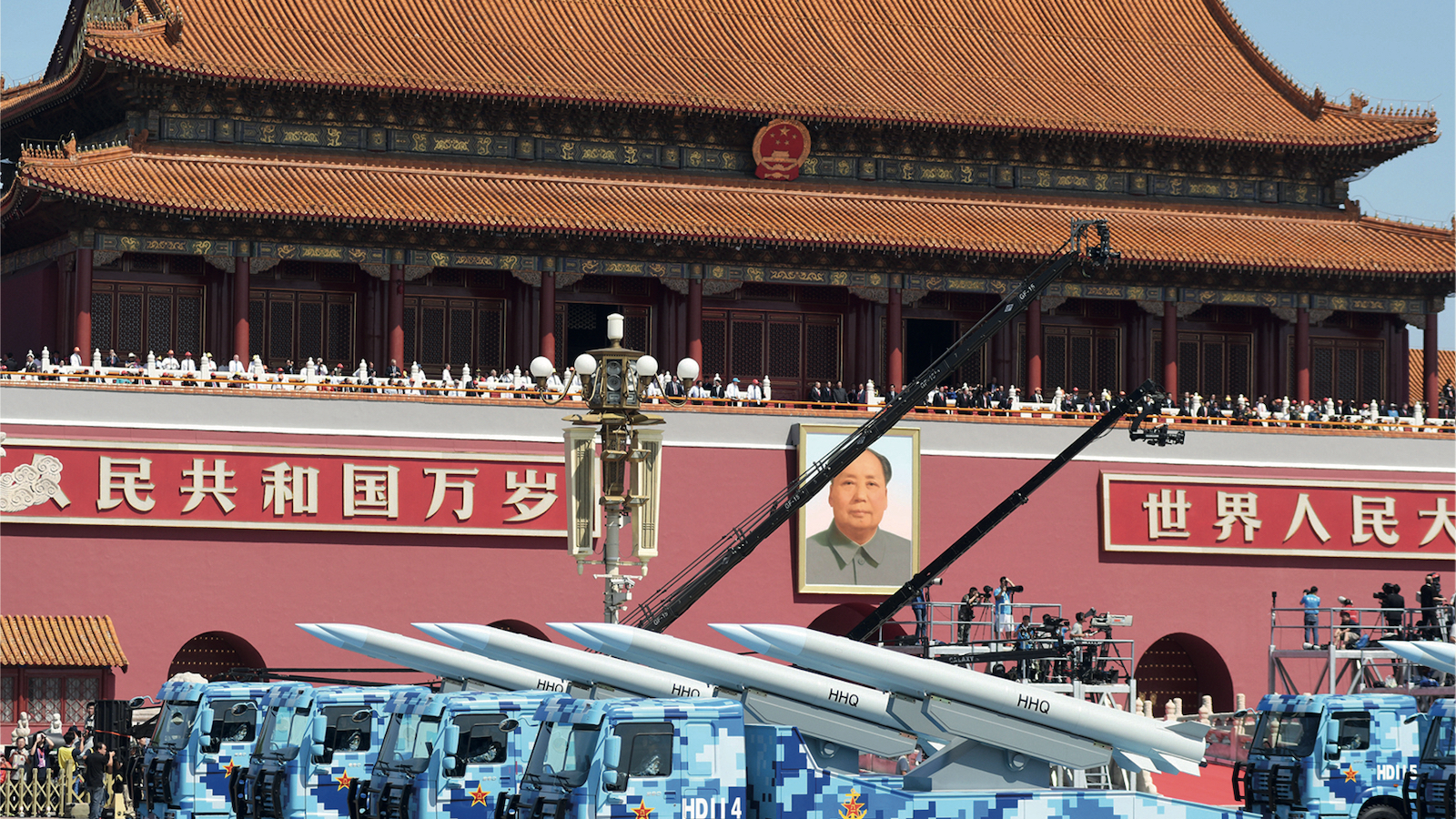

Reviewed: The Fear of Chinese Power: An International History, Jeffrey Crean (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023)

Throw a stone in Washington, D.C., today, and it will hit someone sounding an alarm about China. Phrases like “transnational repression” and “malign influence” have entered the American political lexicon, as concern over China’s growing power and increasing belligerence spreads through the political establishment. Switches across government are flipping from counterterror to Great Power competition. The House of Representatives has seized on TikTok as the embodiment of the Chinese threat, passing legislation that could ban it. And in an election year, the volume will only increase.

The pitch of warnings over China has risen over the last decade, ever since the U.S. foreign policy apparatus began its “pivot to Asia” in 2012. As a policy turn, the pivot was an attempt at a course correction — an acknowledgement that the U.S. had been focused elsewhere, most notably on the Middle East. The conventional wisdom on China shifted: swathes of the Washington brain trust now say America was late to recognize an emerging rival, a fox that engagement let into the international system henhouse. Some have argued that engagement was a mistake to begin with, in a debate now tinged with urgency. Few in Washington, where I’m writing from, now advocate closer relations with China.

Yet as historian Jeffrey Crean argues in his book The Fear of Chinese Power: An International History, little about this national apprehension is surprising or new. If anything, a key take-away is that the era of welcoming China into international institutions with open arms was the anomaly, not the norm.

Xi Jinping’s techno-authoritarianism is only the latest model of the China specter: for at least 150 years, prominent Americans have feared China. Crean looks back to 1879, when Ulysses S. Grant was traveling in a weak and rebellion-riven Qing China, predicting that the day was “not very far distant” when the Chinese would become “dangerous rivals to all powers interested in the trade of the East.” In 1972, Richard Nixon penned a warning from Beijing, as a guest of Mao Zedong’s impoverished and mismanaged nation, that if “all the people of the world” did not put forward their best efforts to match the Chinese challenge, they would be “confronted with the most formidable enemy that had ever existed in the history of the world.” In line with the apocryphal Napoleonic quote (that Crean suggests likely originated from China itself, attributed to a foreigner to give it more weight), these outsiders saw China as a sleeping giant that would someday shake the world.

Crean contends that fears of China are unique. Historically, Western nations have long worried about what the China scholar Michael Barr called China’s “imagined power” in his 2011 book Who’s Afraid of China? The Challenge of Chinese Soft Power. Crean expands on this to posit that this cultural other-ing allowed the fear to flourish, regardless of the strength or weakness of the Chinese state, the ideology of its rulers, or the shape of the surrounding international system. So why did so many leap to the conclusion that China posed a credible threat?

Xi Jinping’s techno-authoritarianism is only the latest model of the China specter: for at least 150 years, prominent Americans have feared China.

While he references Genghis Khan’s rule over Eurasia in passing, Crean starts the book (somewhat arbitrarily) in 1880, arguing that fear of China emerged in Europe around then, as the product of “imperial anxieties of reverse colonization.” One anxious imperialist, Germany’s militaristic Kaiser Wilhelm II, “proudly became the avatar of the gelbe gefahr,” the collective racialized fever dream known as the Yellow Peril, and was such an enthusiastic booster that he is sometimes credited with coining the term. (The phenomenon later spawned a wealth of popular culture artifacts cataloged in other books, such as Yellow Peril!: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear.) The Kaiser’s era was also the heyday of Social Darwinism and invasion novels, such as 1898’s The Yellow Danger, which depicted a Chinese takeover of the European continent. Many became convinced that China posed a threat not just to European security but to European civilization. The irony is, of course, that the crumbling Chinese empire had been failing to defend against attacks from European powers for decades, such as in the Opium Wars.

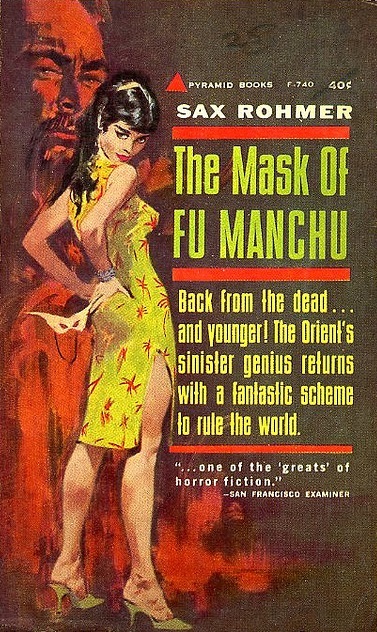

Rohmer, 1962 (Ronnie Lesser)

Trepidation about China as a nation became inextricable from trepidation about the Chinese people, which found expression as anti-immigrant sentiment. Even virtues like industriousness or intelligence, applied in stereotype, were recast as threats. This xenophobia manifested in popular culture through characters such as the archetypal supervillain Fu Manchu. Over time, the acceptability of the term “yellow peril” faded, and after World War II, focus shifted to China’s political ideology and its military and economic strength. But under the surface, Crean argues, “the old stereotypes of the supposedly bygone racialist era persisted.” It is these “persistent racialized stereotypes of the Chinese” that Crean says remain at the heart of China fears, which he finds take four forms: cultural, demographic, economic, and strategic (usually military).

In Crean’s formulation, not only is fear of China unique, but it manifests in its most potent form in the United States. For this reason, he frames the book largely in American terms. Anti-Asian sentiment drove the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, but after World War II, the Chinese Nationalists’ loss of the mainland, and the emergence of the People’s Republic in 1949, escalated American fears. These events, Crean says, “popularized American Sinophobia as never before by merging the Yellow Peril with the Red Menace.” Cold War science fiction, such as Robert Heinlein’s 1959 Starship Troopers, took the heightened fear to its logical conclusion, depicting a world in which, as Crean puts it, “the rise of China meant the death not only of Western supremacy but of Western liberal democracy.”

Fear periodically made room for gold-glinted hope. Over the ages, both capitalists and missionaries have approached the Chinese people with evangelical zeal, dreaming of converts. The People’s Republic of China banned missionaries in the 1950s, and in more recent decades has tried to edge foreign companies out of its market. Hope may have soured, but engagement begat entanglement, tying the two nations’ economies and politicians’ hands.

The cognitive dissonance between fear and hope (or as some might less charitably put it, greed) leaves American leaders and policy thinkers resorting to invented words. Like schoolyard “frenemies,” U.S. foreign policy has earned clumsy portmanteaus like “coopetition” and “congagement” to describe its dual impulses toward China. Enmeshed in the global economic system, and resistant to the U.S. ideal of a global political system, China is variously portrayed as a trade partner and a financial manipulator, a center for innovation and an intellectual property thief.

The Biden administration’s China strategy (“invest, align, compete”) likewise tries to strike a difficult balance between critique of China’s political system and recognition of the economic interdependency that keeps that system afloat. Their solution has, in part, included moving to lessen China’s economic leverage over U.S. supply chains. In 2023 “de-coupling” was remade as a post-pandemic “de-risking” to ruffle fewer feathers, but the general direction is clear.

In Crean’s formulation, not only is fear of China unique, but it manifests in its most potent form in the United States.

The Fear of Chinese Power progresses chronologically rather than thematically, narrating key developments in modern China. This suits its inclusion in Bloomsbury’s “New Approaches to International History” series, designed for students, but its history lessons occasionally overwhelm the argumentative line. Crean’s trail leads to the present, when the demographic, economic and strategic elements of his historical case seem to crash together, topped with a Covid-inspired reboot of old China plague narratives. Given this, the present day gets short shrift, with only a handful of paragraphs in the last chapter covering the years 2017 to 2023, and no mention of a resurgence in anti-Asian bias in the United States. Glossing over these recent developments, Crean concludes tepidly that while other nations “are correct to worry about the rise of China,” they should “fear their own myriad shortcomings even more.”

Fear spurs the population out of complacency, but it does not guarantee a nuanced policy discussion. At a time when many in Washington want to be seen as doing something to counter Beijing, some monger fear of China as a springboard to elected office or to win broader public platforms, recycling easy tropes to cover for a lack of good ideas.

Yet whether leading or following Washington, public opinion appears to be galvanizing. Recent polling shows that a record 58% of Americans view China as a critical threat to the United States. It’s also a time when a decreasing number know China firsthand. But the appearance of a consensus on China as the day’s pressing issue is illusory. Prominent thinkers call for skepticism of China fear-mongering and the Great Power competition frame. And as Crean would wish, the population appears to worry more about its own shortcomings than the rise of any overseas rival. Despite the attention the PRC garners on the campaign trail, when Gallup asks Americans what they think is the nation’s most important problem, they don’t say China. ∎

Header image: Military vehicles parade past the Tiananmen rostrum in Beijing, 3 September 2015 (Imaginechina Limited/Alamy Stock Photo, via Bloomsbury).

Emily Walz spent several years living in China before moving to Washington, D.C. Her work has appeared in Jamestown China Brief, Washington City Paper, The Minneapolis Star Tribune and The Beijinger, among other outlets.