Reviewed: People’s Diplomacy: How Americans and Chinese Transformed US-China Relations During the Cold War, Kazushi Minami (Cornell University Press, 2024)

Speaking at the Brookings Institution last December, Nicholas Burns, the United States Ambassador to China, lamented the precipitous decline in the number of young U.S. citizens studying in China over the past half decade:

We had 15,000 American students six or seven years ago in China. Last year, we were down to 350 American students in all of China. Now we’ve doubled that population. But 700 American students now doesn’t represent the interest that we have. …

We need young Americans to learn Mandarin. We need young Americans to have an experience of China. We need young Chinese, and there are nearly 300,000 Chinese in our universities, to understand this country, to understand democracy.

Burns has repeatedly argued that the low number of U.S. students traveling to China is evidence of the pressing need to “bring the American people and Chinese people back together again.” Other Biden administration officials have echoed this language, regretting the breakdown of people-to-people exchanges following the Covid pandemic.

With Donald Trump returning to office, the likelihood of reviving these exchanges seems fainter. While U.S. policy toward China is not likely to change significantly, the new administration seems more likely to build on the legacy of Trump’s first term, in which he directed the Department of Justice to investigate Chinese and Chinese-American academics in the United States through the China Initiative, while also ending the Fulbright exchange programs that brought young Americans to mainland China and Hong Kong.

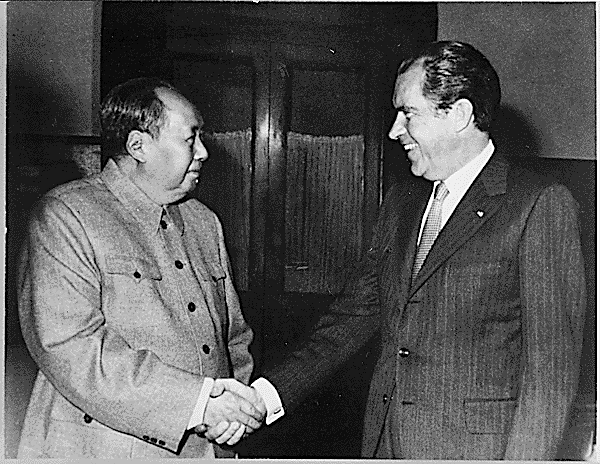

Implicit in calls for a resurgence in educational exchange is the idea that the relationship of the American and Chinese people constitutes a separate stream running parallel to the high-level diplomacy (and more structured track two dialogues) in which the two states engage. There is even the hope that a thick web of cultural and economic connections between China and the U.S. could exert a soothing influence on political tensions. Yet as the flow of people across the Pacific picks up again, it is worth considering the extent to which these exchanges have truly influenced the trajectory of U.S.-China relations since Richard Nixon’s iconic visit to Beijing in 1972 began to normalize relations. Restarting what China has called “people’s diplomacy” (人民外交) between Chinese and Americans is an important and worthy goal, but its track record shows that cooperation between the two nations does not follow naturally from friendship between its populations.

Revisiting the rapprochement of the 1970s, when it all began, is a good start. Fortunately, the topic has come in vogue among Anglophone historians. Several books have been published in recent years on how academics, athletes, musicians, students and all manner of other non-state actors have impacted U.S.-China relations since the 1970s. A new addition to this shelf, People’s Diplomacy: How Americans and Chinese Transformed US-China Relations During the Cold War (Cornell University Press, 2024), is one of the first that attempts to cover the full range of Sino-U.S. people-to-people relations during that decade.

There is the hope that a thick web of cultural and economic connections between China and the U.S. could exert a soothing influence on political tensions.

The author, Kazushi Minami, a historian at Osaka University, works with a wide range of sources in both Chinese and English: state and local archives, memoirs, personal and institutional collections, and interviews with participants. The book is thematically organized around six chapters that explore exchanges in trade, science, education, tourism, sports and art. In each case, Minami explains how these exchanges engendered new private interests, with groups of Americans and Chinese coming to see the advantage for them if the two nations achieved a closer relationship. Unlike other studies that have focused exclusively on academic or cultural contact, Minami includes the development of trade relations in his panoramic overview of “people’s diplomacy,” and his account is attuned to the importance of financial and commercial interests as well as the flow of people and ideas.

Though Minami defines “people’s diplomacy” as being conducted by “nonstate actors, independent of, yet often guided by, the state,” the definition of “nonstate actors” becomes somewhat murky, as the author readily admits. In each of his case studies, Minami examines the work of organizations such as the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations (NCUSCR) and the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), the behind-the-scenes facilitators of many trans-Pacific journeys. It is common knowledge that the Chinese government stage-managed the experiences of foreign visitors to China during the 1970s. In a telling anecdote, Minami describes how Chinese propagandists arranged for a New York Times reporter to observe a brain surgery in which the patient received no anesthesia, only acupuncture, and recited Mao Zedong quotations for the duration of the procedure.

While organizations like the NCUSCR and the National Council on U.S.-China Trade (which changed its name in 1988 to the U.S.-China Business Council) were, and continue to be, non-governmental organizations, their coordination with the U.S. government during the period of rapprochement is well documented and did not go unnoticed by the Chinese. In the Shaanxi Provincial Archives, Minami uncovered a document in which Chinese government officials explained that NCUSCR’s “non-governmental façade” disguised its “intimate ties” to the U.S. government and the CIA. Visitors from the United States were frequently suspected of “snooping for intelligence,” but were also seen as unofficial intermediaries through which messages could be passed to Washington.

Minami’s book makes extensive use of materials from municipal and provincial archives around China, following a general trend in Chinese historical research in which scholars have gone to the local level to track down details that no longer remain in the more tightly regulated central archives. In the Hubei Provincial Archive, Minami found instructions for Chinese athletes on how to keep their eyes peeled for opportunities to put “friendship first” by deftly losing to less skilled foreign opponents in ping-pong exhibition matches. In the Guilin Municipal Archives, he uncovered records of a Chinese tour guide so tall and handsome that the Japanese visitors under his supervision formed a fan club.

One telling detail describes how a female Chinese guide had to listen to a tourist’s whispered confession of marital difficulties: “My wife has not been with me for a long time, and I need your comfort.” These romantic overtures from foreign guests towards their Chinese guides angered government officials when they interrupted carefully choreographed tours. This type of poor behavior by visiting guests was expected from decadent capitalists, but the Chinese side became alarmed when their own guides began to welcome the advances, fearing ideological demoralization and ultimately banning any kind of “fraternization.” This type of granular detail about the logistical and social challenges of bringing Americans and Chinese together brings the human side of this era of exchange to life.

Other scholarly treatments of U.S.-China engagement in the 1970s have a narrower focus. Gao Yunxiang’s Arise, Africa! Roar, China! (University of North Carolina Press, 2021) argues that the relationships of African American luminaries such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson with Chinese counterparts helped both sides understand the “shared struggles of a nation and a nation-within-a-nation.” Elizabeth O’Brien Ingleson’s Made in China (Harvard University Press, 2024) contends that modern Sino-American economic interdependence is the result of an unexpected alignment in the interests of U.S. business leaders and Chinese politicians during the 1970s, wherein the former sought to move manufacturing offshore and the latter offered a seemingly infinite supply of cheap labor. Hongshan Li’s Fighting on the Cultural Front (Columbia University Press, 2024) puts forward a more heterodox interpretation of Sino-American cultural exchanges during the Cold War, framing them as competitive rather than a source of amity.

Pete Millwood’s Improbable Diplomats (Cambridge University Press, 2022), meanwhile, focuses on case studies such as ping-pong diplomacy and musical exchanges, arguing that cultural ties became increasingly important in the middle of the 1970s, when high-level negotiations had all but frozen. Millwood’s detailed account of the political and logistical challenges that accompanied these trans-Pacific encounters is also a welcome corrective to more triumphalist popular depictions of the period, such as the PBS documentary “Beethoven in Beijing” about the Philadelphia Orchestra’s 1973 trip to China.

People’s Diplomacy shows that each form of exchange followed roughly the same trajectory: the grand ambitions of non-state actors at the start of the 1970s were stymied by the contentious politics of the decade’s middle years, until the ascension of Deng Xiaoping in late 1978 finally aligned their schemes with the economic and political ambitions of the Party-state, allowing for breakthroughs. This recurring narrative is not a strike against the book — it accurately reflects the bird’s-eye view of people’s diplomacy in the 1970s. Yet it does make one question the extent to which the relationship between these exchanges and high-level diplomacy was reciprocal.

It rings hollow when U.S. officials such as Nicholas Burns bemoan the breakdown of sub-diplomatic exchanges, even as they and their Chinese counterparts pursue aggressive policies that have brought the bilateral relationship to its lowest point in decades.

It is evident that vacillations in international relations guide the rise and fall of person-to-person exchanges, but the moments when those exchanges influence the course of geopolitics are harder to discern. This gap between the perceived importance of people’s diplomacy and its actual impact on U.S.-China relations seems linked to the outsized importance that exchanges have on the people who participate in them. The ability to travel across the Pacific and interact with counterparts in the U.S. or China has profoundly shaped the careers of several generations of students, artists, businesspeople, academics and politicians (the most recently notably example being Tim Walz), but it is less clear that they have made any actual impact on bilateral relations.

This is not to say that societal contact has no effect on U.S.-China relations — greater economic interdependence and cultural exchange certainly play a role in counterbalancing geopolitical competition. Yet the lesson of the 1970s does not seem to be that people-to-people contact was a parallel stream of U.S.-China diplomacy, guiding leaders back to cooperation when they strayed into conflict. Instead, the historical record suggests that people’s diplomacy is highly susceptible to the political headwinds of U.S.-China rivalry, and that hard-won victories in the cultural and academic realms are easily undone by ephemeral political tensions.

Indeed, the political disruptions to the “people’s diplomacy” that Minami chronicles in the 1970s sound virtually identical to the stories that have proliferated in the last decade: visiting researchers being accused of espionage; visas being denied due to the applicant’s political statements; tours privileging symbolism over substance. Given that people-to-people ties have always been linked to elite politics, it rings somewhat hollow when U.S. officials such as Nicholas Burns bemoan the breakdown of sub-diplomatic exchanges, even as they and their Chinese counterparts pursue aggressive policies that have brought the bilateral relationship to its lowest point in decades. Now more than ever, we must recognize that cultural exchange with China is not divorced from the politics of the moment, but is intimately tied to the ebbs and flows of Sino-American competition. ∎

Header image: American George Brathwaite (left) returns a shot to China’s Liang Geliang (right) at the United Nations in 1997, during an exhibition match organized by the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations for the 25th anniversary of “Ping Pong diplomacy,” featuring players from the original 1972 teams. (Henny Ray Abrams/AFP/Getty)

Anatol Klass is a postdoctoral fellow with the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. He is a historian with research interests focused on 20th-century China and the development of institutions that craft Chinese foreign policy. Klass received his PhD in modern Chinese history from the University of California, Berkeley.