Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

In 1989, Hongbin Li sat for the gaokao, China’s college entrance exam. The high score he achieved launched him on his trajectory out of the Jilin factory in which he had grown up to his position now as co-director of the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions. An economist who taught previously at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Tsinghua University, Li’s research areas include the transition and development of the Chinese economy and the Chinese education system. His new book, The Highest Exam: How the Gaokao Shapes China (Harvard University Press, September 2025), co-authored by economist Ruixue Jia with assistance from Claire Cousineau, pulls from their personal experiences and quantitative research to examine how the gaokao has impacted modern China.

In a Q&A from our sibling site The Wire China, now ungated here, Evan Peng asked Hongbin Li about the China’s highest exam’s past, present and future.

Evan Peng: Can you explain the gaokao system?

Hongbin Li: Gaokao, which we translate to “highest exam,” is basically the college entrance exam in China. It determines which college you are going to, or whether you can go to college or not. This nationally organized test is normally held over three days in early June every year.

Earlier in high school, each student is divided into science or social science tracks. For the science track, you study subjects like physics, biology and chemistry. For the social science track, you study geography, history and politics. They both study math, Chinese and English, but for the science track, the math is harder.

For the gaokao, students are tested on six or seven subjects over two or three days, and then they get a score; college admissions are purely based on this one score.

How did such a system emerge in China?

The gaokao was first administered in 1952, after the People’s Republic of China was founded. But it was based on an older exam called the imperial exam, which is around 1,400 years old. That was the exam given by emperors to select their officials. A person could take it many times, and once he passed it, he would become an official, and then he could take a further exam to become a higher ranking official.

The gaokao in modern China is only for college admission, but once a person gets into college, they then have a chance to become an official. So though they are a bit different, the gaokao and the old imperial exam more or less have the same basic logic.

In your book, you describe the gaokao system as a centralized hierarchical tournament. Why do you term it this way?

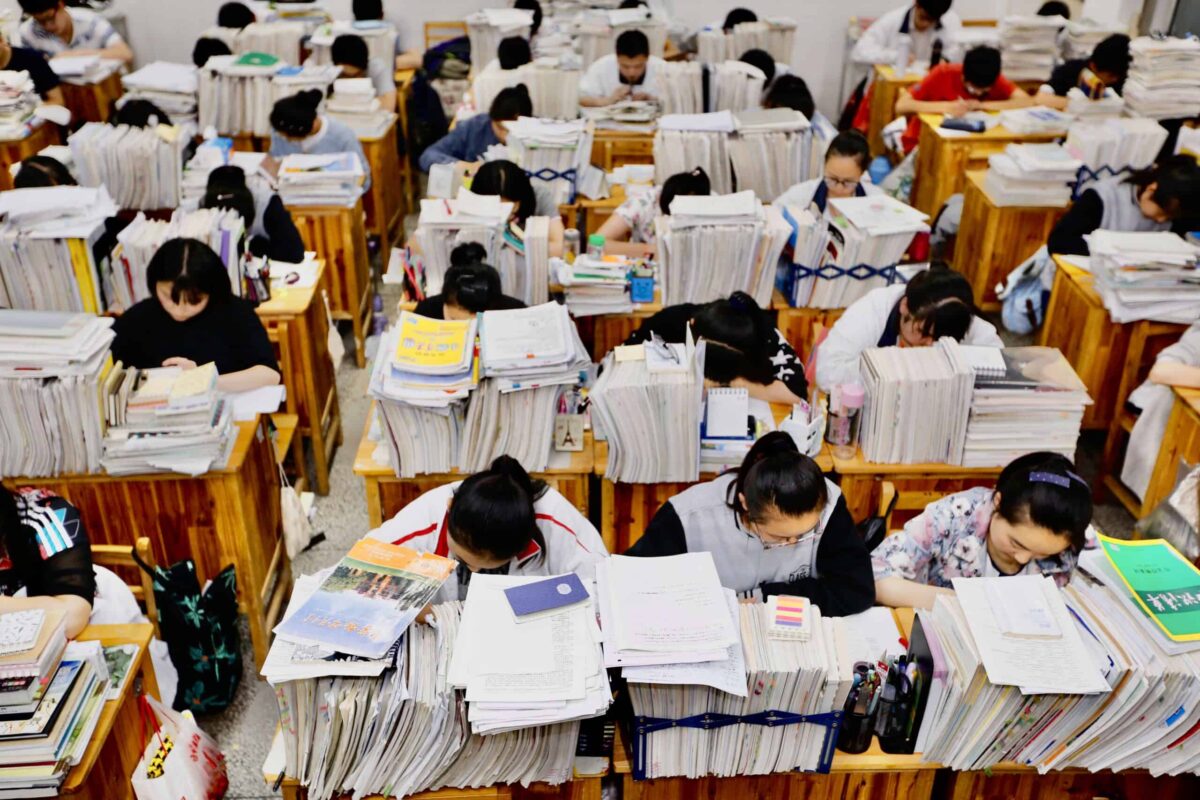

I have been studying China’s economy for many years. The society is organized as many different tournaments. Education is probably the first tournament every individual in China experiences. In China, the schooling system is more of a selection mechanism than an education mechanism. In other words, what you learn matters, but it’s not as important as who you are in the system. Basically, the purpose of the system is to test you and select the best people into the higher levels of the hierarchy. That’s the purpose, and that’s why we call it a tournament.

It even starts from first grade; a six-year-old has to be tested into elementary school. At the top schools, entering six-year-old kids will normally be able to do simple addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. They can already recognize maybe 2,500 Chinese characters. Basically, they can read and do math. For a six-year-old, you might think these are the things they would learn in school, right? But because there’s a test, parents have their children study even before getting to school to get into the best elementary school. Only after you get into the best elementary school do parents believe the student can get into the best middle and high schools, then the best college. That’s why it’s a tournament system.

It’s hierarchical because which school is the best, which city is the best, which college is best — everything’s ranked. In the U.S., we don’t exactly know which college is the best. There’s a debate, right? In China, colleges are ranked clearly, with lists made by the government. The top two are very clear (Peking University and Tsinghua University), then the next are called the top nine, and then the top 40 and the top 100 or so.

These are all determined by the government, and government funding is allocated depending on the rankings. That’s why there’s a clear hierarchy in colleges — and also in primary and secondary education. In every city there is a clear ranking, where a certain high school is number one, another is number two, and so on. The whole thing is hierarchical.

What does it mean that the whole system is centralized? Education is administered by the Ministry of Education, which also has divisions in every province and every city which report to the central government. All the colleges are administered by the Ministry of Education. For example, Peking University’s president is a vice minister, and he reports to the minister of education.

The gaokao exam is also centralized. People are tested on the same day. Admissions happen at the same time. Admissions quotas are set by the central government. Also the education content is centralized. What you learn in school is all determined by the central government.

How do economists analyze returns to education, and how do such analyses apply to the Chinese education system?

The classic model is like this: We normally say the cost of education is time. And basically we want to know, when you spend one more year of your time in school, how much additional income does it bring? So you compare a college degree holder to a high school diploma holder: In many countries, including both China and the U.S., a college graduate has around a 40% higher income than a high school graduate, meaning, since the college graduate has four more years of education, each year of college has a 10% return.

But that model is based on market economies. It assumes that everything you get is from the market. So if you work for a company, and they pay you, that’s all your income. China’s system is different. The most important sector is the state sector: government officials, state-owned enterprises, and also a lot of the so-called public institutions, like hospitals, colleges and schools. These employ a lot of people.

The pay for these people includes cash income, but that’s only part of it. They also have other benefits. For example, if someone grew up in a rural area of Gansu province, and he tested into Tsinghua, he may stay in Beijing and get a Beijing hukou. And the most valuable thing in China is the hukou: if you grew up in Beijing, Shanghai, etc. and hold that hukou registration, you have a built-in advantage in many things. College can get you a state job, which then gets you a desirable hukou, which is really valuable.

But if you get a hukou, how much is its cost or monetary value? There is none, as there’s no market. Also, in those jobs there are often housing, healthcare, pension and education perks, all benefits that we sometimes do not observe in the data. Even if we observe it, we don’t know how to assign values to them.

That’s why when we try to apply the returns to education model to China, the total “income” a college graduate can earn is not fully observable. All the models that use observable income, including many of my own works, really underestimate the true returns of education in China.

How has Chinese society been shaped by the gaokao system?

Because the system is so important, because people know that scoring high on the exam does have a high payoff, parents really invest in students’ testing skills. That’s why tutoring is so widespread in China, and why it was so prevalent that the government even decided to ban the whole industry a few years ago.

Even poor households still spend a lot of money on education, because it’s their only hope for the kids to be upwardly mobile. Testing well and getting into a good college is a way that China maintains social mobility, which is very important.

This type of behavior, the cramming, the long hours — the common perception is that it’s a cultural thing, and it’s unreasonable. But you argue that it’s actually very rational behavior. Can you explain that?

Yes, it’s rational from both the individual perspective and the ruler’s perspective. For individuals, we show that education has a high return. In China today, the best jobs are still government jobs, either working for the government itself or for state-owned enterprises. Those jobs are good because they not only provide security and high pay, they also provide some social benefits that cannot be achieved otherwise.

When you get an official job, there are a lot of other benefits. China has the so-called “three mountains,” or three areas of high expense: housing, healthcare and education. If you become a government official, you may be assigned housing that has a high market price but a low purchase price — basically, it’s subsidized. You have free medicine. You can go to the best hospitals free of charge. Your children can go to a good school. There may be other implicit social benefits, like social status, and so-called “grey” income. There’s a high payoff for individuals; that’s why people really care about this.

From a ruler’s perspective, this is a good system because it maintains social mobility. A society with social mobility will be more stable because people have a chance at making it. The trick of this is that even though the chance of getting into a good college could be low, as long as there’s a chance, people feel the need to try hard.

Moreover, the test is transparent, with a simple objective score. If you do well, you get into college. If you don’t do well, you don’t get into college. People who do not do well generally believe that they deserve it because other people are smarter, or they work harder, and so those people deserve better outcomes. Because everything’s so transparent, people know who is smart, who is working hard. So people don’t blame the system.

By contrast, if you have a non-transparent system, then people might feel the system is corrupt. That’s an issue; when people are not happy with the system, society will not be stable.

A system like the gaokao also helps the ruler select talents to work for him. Smart people will help him govern the country, which is good for him. The ruler can also determine what is taught in the school curriculum. So all these features the rulers like; that’s why I don’t think they want to deviate from it.

Other than those positives from the ruler’s point of view, are there other reasons the system has been so enduring?

The division between elites and non-elites is a big issue in the U.S. today too. How do we select or decide who are the elites in society? College is one of the channels to sort people into elite/non-elite. And the question is, what’s the best way to do this? It’s really hard to know. I don’t think we have a good answer. But if the society is corrupt in other ways, then people at least want a transparent system.

Suppose China adopted the American system, using a holistic admissions system which is partially objective and partially subjective. Chinese people would think the system was corrupt, because China is really a corrupt country. If you want to see a doctor, you pay a doctor a red envelope to do an operation; parents give teachers red envelopes so that teachers favor their child. This petty corruption is really popular. So people wouldn’t trust in any system that has elements of subjectivity. That’s why Chinese society has a consensus that the gaokao is the most accessible system.

Another important thing is that people in China believe in meritocracy. If you look at surveys by social scientists, and if you ask parents what they value most, Chinese people say working hard is a very important value we should instill into our children. You ask an American, they might say hobbies are also very important — though Americans are also hard working. But if it’s down to sacrificing your leisure time to work, most Chinese don’t care. That’s why you observe people voluntarily work longer hours in China. They work on Saturdays, Sundays in many places. They want to make more money, and they value working or making money more than consumption and leisure.

Here, in the U.S., people work hard, but they also care equally about leisure and consumption. What that might suggest is that Chinese society values working and income, which is directly affected by the gaokao, more than anything else.

In China, the schooling system is more of a selection mechanism than an education mechanism. What you learn matters, but it’s not as important as who you are in the system.

What inequalities are there in such a gaokao system, and how does that compare to a system like in the U.S.?

Once you reach the stage of taking the exam, the exams seem to be fair and objective. But before reaching that point, it takes 12 years of training. It’s like a tennis tournament; if you have a good coach, and you have spent a lot of money on training, then the result may be better, and you can score higher. That means people from richer families definitely have an advantage.

If you compare the top 10% income group to the bottom 10% income group and see the respective chances that their kids will get into China’s top 5% of colleges, the ratio is 2.5. Basically, if I’m in the top income group, the chance I get into an elite college is 2.5 times that of the chance for the bottom income group. This is very unequal.

But the U.S. is even worse. The same ratio for American colleges is 11:1. This gap is easy to understand, because in a holistic admissions system like in the U.S., good applicants need more income because of all the extracurricular activities that are expected. You need money to do things. If you have money, you can also hire a college counselor who will help you with the essays. If your parents are well off, you can buy a house in a district with a good school, or you can also go to a private school. You can see that wealth is more impactful here than in China, actually.

Let’s come back to China’s inequality. The quotas for each college are also allocated by province, and they are not evenly allocated. The allocation in quota spots by the central government is in consideration of governing the country. To govern the country, the most important places are the elite cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, and the ethnic minority regions, like Xinjiang and Tibet — the central government gives them more quota spots, so that they remain or become more loyal to the country.

You say the schooling system is more a selection mechanism than an education mechanism. Can you explain why?

In any society, there are three main benefits from going to school. First is to learn things, second is to make friends and connections, and third is a label — basically, like in China, the most important thing is which college you went to. This is the label you have all your life. So given the existence of this gaokao “tournament,” the most important thing is: who is the champion? Who is in second place, in third place? This is more important than what you learn.

Learning is only secondary in this system. That doesn’t mean that they don’t learn. Students work hard for 12 years, so they still learn something. For example, Chinese people are pretty good at math, and at STEM subjects, but they are less likely to be able to debate. In high school, they never have a chance to do that. That’s why many people criticize the Chinese system, for basically killing people’s curiosity and creativity. It could be true, but there’s no concrete evidence. I see a lot of Chinese people from different colleges in China, and when they come to the U.S., they still are creative.

You talked about the government crackdown on tutoring. What other types of reforms has the central government considered to mitigate some of the negative impacts of the gaokao?

On the tutoring crackdown, the problem is that cracking down on training doesn’t solve the problem. You cannot force people not to practice. They will do it anyway. By cracking down, it’s just making it more expensive. Even if you don’t allow big companies to do tutoring, many small tutors are still out there who will, given the demand for it. High income parents want their kids to test better, right? They can afford it, and they can pay a private tutor. When it’s run by the open market, it’s cheaper, but when it’s run by the black market, it becomes more expensive. It creates more inequality.

But yes, there are other reforms. For elementary schools, students living in the school district zone don’t have to take an entrance exam. As a consequence, housing in districts with good schools can become very expensive. So one reform that has been instituted is a randomization in the assignment of students to elementary schools.

So this kind of reform does happen, but given that there is still the final gaokao “tournament,” competition will always be there. What the government can do is to really help the poor to have an even playing field by, for example, subsidizing schools in poor and rural regions. They are already doing that. The Chinese government provides a lot of money to the schools. They build beautiful schools, and their classrooms are better even than classrooms in the U.S. They have the best equipment, computers, everything. The only issue is that they don’t have good teachers, because good ones don’t want to go to poor regions, they want to live in a big city.

It’s hard to solve. I think one thing you can still do is to have some kind of affirmative action. Basically, you give some quota spots in colleges to the really poor regions, or poor families based on income. But it’s hard to do. You could give a certain county two spots, but it could then turn out that the two richest families in the county got the two positions.

How has China’s educational culture, shaped by the gaokao system, been exported elsewhere?

When Chinese people immigrate to other countries, they are still used to the gaokao system. They may come to the U.S., but they still try to seek the same kind of process, which is not what exists. But they will do aspects of the system themselves anyway. For example, a lot of Asian parents, especially Chinese parents, if they are not satisfied with the speed of classroom teaching or instruction, will hire a tutor or tutor their children themselves. They also care about the children’s grade ranking in the school or their GPA, which also justifies hiring tutors. They can learn the material before the teacher in school teaches it.

The issue is, what if other parents don’t like this? Then there’s a kind of debate and argument in the community. In the end, this is a democratic country, and you make decisions by majorities, by voting. That’s why in many of the school districts with a lot of Asian families, the competition between students is a big issue for the school board members. People really pay a lot of attention to the campaigns every time for the school board elections.

Chinese parents care about having one single, transparent, objective measure in the school system overall, and especially for college admissions, since they just don’t trust any sort of subjective system. At the national level, the Harvard case, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, is a very good example. In that case, a group of Asian American parents sued Harvard for its admissions practices and use of personality ratings. In the end, the Supreme Court ruled against Harvard and got rid of affirmative action.

There are also recent studies of white flight, where white families basically don’t want their kids to be subject to such intense competition and stress, so they choose to migrate away from communities and schools with a lot of Asian families.

The problem is that this kind of testing system has been within Chinese culture for such a long time. Chinese people are so used to it. It may take generations to change. But given that Chinese people keep immigrating to this country, this will affect the education system here. Also importantly, what if that system has some upside? What does it mean that the kids do succeed with those tactics in this system? Other parents may also want to learn or copy from this. So I think this will be an ongoing issue for a long time in this country. ∎

Evan Peng is a journalist based in New York. His work has appeared in POLITICO and Bloomberg.