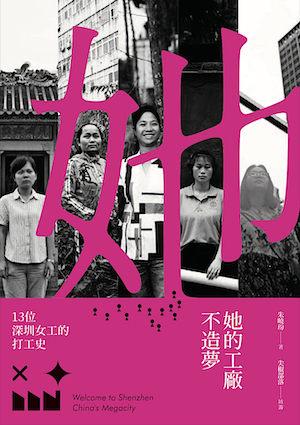

Reviewed: Her Factory Makes No Dreams: The Working Stories of Thirteen Shenzhen Female Workers, Zhu Xiaobin《她工廠不造夢》朱晓玢 (新銳文創, 2022)

Western scholars often depict Chinese female factory workers as a vulnerable group, oppressed by capitalism and patriarchy, struggling with their livelihoods and dignity. Video platforms such as Douyin, China’s TikTok, use beauty filters to promote videos of “factory girls” (厂妹) as clickbait. Government propaganda from the All-China Women’s Federation portrays female workers (女工) as “International Women’s Day Red Banner Pacesetters” who dedicate their personal lives to collective honor. What do all of these groups have in common? They have become self-appointed spokespersons for Chinese female workers, whose own complex narratives are missing.

The voices of female factory workers in China are hard to find. You may come across their own short videos on Douyin, showing them rapidly assembling parts on the factory line, or buying groceries in urban villages, or raising their children. These fragments, like bubbles in an ocean, are scattered by big data. If you are not a worker in the same factory yourself, it is unlikely you will hear about them. Yet each of their stories could be a novel.

Her Factory Makes No Dreams: The Working Stories of Thirteen Shenzhen Female Workers (她的工廠不造夢) by Zhu Xiaobin (朱晓玢), a Chinese journalist born in 1987, tells those stories. It was published last summer by Xinrui Wenchuang Press (新锐文创), a small Taiwanese publishing house, and is yet to be translated into English. The book records the life trajectories of 13 women who work in factories in Shenzhen. We learn about their childhoods, their relationships with family, their logic in job-seeking and choosing a partner, and the joys and sorrows of their life and work. The distance between reader and subject narrows, even if only a little.

The story of a worker called Xiaoqin (all names in the book are pseudonymous, to protect them from the repercussions of speaking out) left the deepest impression on me. Her early life, she says, was characterized by the word “escape.” Born in the 1970s, Xiaoqin (小琴) grew up in a rural area of Hunan province. She dropped out of school in the second year of junior high, and earned a living by selling homegrown vegetables. To escape from this impoverished and monotonous life, she and several girls from the village found jobs in the southern factory city of Dongguan, arranged by their county labor bureau.

Xiaoqin started work in a Dongguan factory, producing toy clocks. It was the first time she had seen a children’s clock that could make noise and move; she found them delightful. Yet conditions in the factory were terrible: long working hours, poor food quality in the canteen, harsh and cramped living conditions, and compulsory body searches when entering or leaving the factory. The worst problem was that the factory never paid her wages.

Along with the other girls from her village who were working there, Xiaoqin planned to escape. They were unfamiliar with their surroundings; she didn’t even know where the bus station was. They had no money, and the factory’s security was strict. Due to the arrangement with their labor bureau, they felt they couldn’t just quit their jobs like normal workers could. One of the girls discovered a sewage drain, quietly crawled into it, and found it led to the outside. So, just like a prison-escape movie, the girls abandoned their belongings, squeezed their bodies through the sewer and escaped the factory.

Such thrilling and horrific stories are rarely reported in mainstream Chinese media. The Chinese state is very sensitive to worker rebellions, because according to Marxist theory, when workers unite it is a precondition for the proletarian overthrow of a bourgeois regime. In the summer of 2018, workers at a Jasic Technology factory in Shenzhen tried to unionize in protest at their working conditions. Marxist student groups from across the nation flocked to Shenzhen to show solidarity with the workers, but the authorities deleted their stories and arrested both workers and student protestors.

Her Factory Makes No Dreams tells the stories of individual rebellion by female workers: escaping from arranged marriages; choosing to live alone instead of in abusive domestic situations; going on strike against unfair working conditions; and defying patriarchal society by participating in feminist movements against sexual harassment. The author uses a straightforward tone to narrate their life journeys, and at the end of every chapter she transcribes a conversation between them. These oral histories are the most captivating aspect of the book. Zhu refrains from inserting her own views into the writing, but respectfully presents the stories and complex emotions of these women just as they are.

An especially marginalized group among female factory workers is the LGBTQ community. The last protagonist in the book, Duo Duo, is a lesbian worker who refers to herself as “a unique speck of dust.” She suffers not only the tiresome labor that other workers endure, but also judgment from those around her regarding her sexuality. She cannot come out to her parents, because even though she left her conservative hometown, she doesn’t want her parents to be subjected to gossip and criticism from their relatives. She falls in love with a straight woman, and experiences painful loneliness. As I read her story, my emotions fluctuated wildly along with her own ups and downs.

Zhu Xiaobin’s interviews reminded me of the 2008 book Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China by former Wall Street Journal correspondent Leslie Chang, which followed the stories of two female workers rising from the assembly lines of Dongguan. Both books are straightforward records of the lives of female workers, without adding personal judgment. However, Chang’s book was criticized by some Chinese readers for selectively choosing only two female workers’ stories, leading them to question whether the cases could represent typical factory girls. Zhu’s book records a more diverse group of female workers, encompassing a variety of ages, sexual orientations and life trajectories. Some of them achieve upward mobility, while others – like the majority – continue to struggle day by day for survival.

Like a prison-escape movie, the girls abandoned their belongings, squeezed their bodies through the sewer and escaped the factory

Stories like these may be even more difficult to write in the future. The publication of Her Factory Makes No Dreams was coordinated with Jianjiao Buluo (尖椒部落), a non-profit website advocating for female worker rights since 2014. They empowered female workers to tell their stories, enabling society to understand their marginalized status. Yet in 2021, Jianjiao Buluo was officially ordered to shut down. The police suspected that the platform was being funded by foreign forces to engage in feminist and labor movements, two highly sensitive topics in China.

Following the Jasic incident, labor NGOs in southern China were gradually shut down and worker’s rights activists were subjected to varying degrees of harassment, detention and imprisonment. Social institutions that were deeply rooted in industrial areas were swept away, leaving workers without activity spaces outside their factories. Previously they could rely on mutual support networks, attend artistic events and publish their own stories. Now their voices are shattered, or scattered across heavily monitored social media platforms.

Even in this book I could see the cautiousness of the author, an experienced former journalist who studied in Hong Kong. Reporting the stories of female factory workers inevitably touches upon sensitive topics that can provoke the ire of authorities: gender inequality; exploitation of workers; “stability maintenance” measures to crack down on protest; an unfair household registration system; and shocking wealth disparity. I could imagine the author doing her utmost to present the authentic life experience of her interviewees while also trying to protect their personal information. After publication, many individuals associated with the book were interrogated by the police.

For the same sensitivity, the book is published in Taiwan and cannot be sold in mainland China. Fearful of the political risk associated, the publisher did not promote it heavily and its sales are low. On China’s most popular book review website, Douban, the book’s rating is displayed as “insufficient ratings” without a score. Among the eight customer reviews, readers expressed encouragement for its subjects, lamenting the hardships of their working lives and the vicissitudes of life.

Where once the voices of female workers were heard, now the Chinese state has dismantled these windows into their lives. This is lamentable for the Chinese people, not only because they no longer have the opportunity to hear the stories and demands of workers from different classes, but because a greater crisis lurks ahead. With declining employment rates in China, low birth rates and escalating social conflict – when stability maintenance policies can no longer quell the anger of those who face injustice – without these bridges to the public, will the people still be able to navigate their difficulties peacefully and without violence? ∎

Header: Workers at an e-cigarettes battery factory in Guangdong province.

Zheng Churan is a Chinese feminist activist. Since 2012 she has organized young women in China to engage in policy advocacy and public education, and has also advocated for female worker’s rights. In 2015 she was detained by the Chinese government for her activities, along with other activists known collectively as the “Feminist Five”.