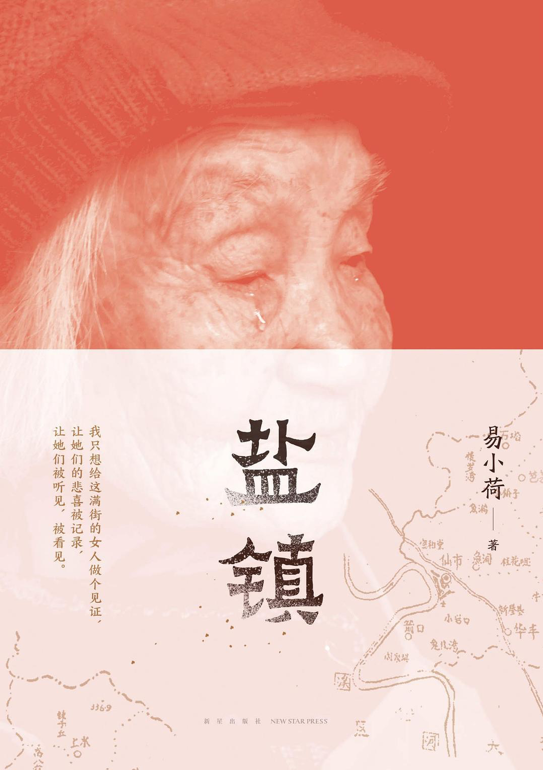

Reviewed: Salt Town, Yi Xiaohe《盐镇》易小荷 (新星出版社, 2023)

In 2014, Yu Xiuhua, a disabled writer from the countryside of Hubei province, went viral for her poem about spring, sex and traveling across the Chinese hinterland. ‘Crossing Half of China to Sleep With You’ seemed to signal a cultural breakthrough for rural Chinese women: after centuries of disadvantage and neglect, they had found a voice.

Yet how much really changed? There have been tremendous achievements in poverty alleviation in China over the past three decades: the rate of extreme poverty fell from 66.3% in 1990 to just 0.3% in 2018. Yet when it comes to gender imbalance, legal protections and social attitudes have not caught up. A 2016 report found that 97.5% of rural parents say they will prioritize sons over daughters if they cannot afford to send all their children to school.

Almost a decade later, the substance of Yu Xiuhua’s moment feels emptied out. Her poem of rural resilience is now a cheap signifier for city-dwellers to earn approving nods from fellow cultured folk. In Salt Town (盐镇), a new Chinese book by journalist Yi Xiaohe (易小荷), the author dismisses the village she writes about as too philistine to recognize the literary reference:

One struggles to locate any traces of ‘culture’ here; carrying a Yu Xiuhua poetry collection around in my arms does not earn me any respect. The people here rarely ever care about any grandiose topics; they lay their sight upon what is closest, and only money can mean anything for a person’s dignity.

The thorny lives of Chinese women in the countryside is the bread and butter of Salt Town, which was published in mainland China in February 2023 by New Star Press and is yet to be translated into English (translations in this article are my own). The book sat on the trending list of Douban, China’s most popular review platform, for months after its release. According to OpenBook, a Beijing-based publishing data analytics firm, it was the seventh best-selling nonfiction book in China.

Salt Town tells its story in chapter profiles of ten women of different generations, occupations and social statuses, all living in the small town of Xianshi, in Sichuan province to China’s west. There is a former brothel madam, a cotton fluffer’s wife, a hotelier, a lesbian village cadre, a struggling mother, a butcher’s daughter, a beautician, a divorced university dropout, an orphaned migrant worker, and a 17-year-old prostitute. The eleventh, un-chaptered character is the author herself.

Words of rural resilience are now a cheap signifier for urbanites to earn approving nods from fellow cultured folk

Yi Xiaohe rose to prominence in the early 2000s, stationed in Houston, Texas, as the first Chinese journalist to cover the NBA. Later, based in Shanghai, she had an illustrious state-media career spanning Xinhua, Southern Weekly and China Newsweek. In 2016 she left print for digital media, founding the edgy publication Seven Writers together with six other colleagues, including the dissident writer Murong Xuecun. The site boasted hundreds of thousands of readers, but in 2017 censors erased it from the web.

Undeterred, in 2017 Yi founded another media start-up, Soulker. This picked up where Seven Writers left off, publishing current affairs commentary and culture longreads. The site covered Covid extensively in 2020; one photo essay by Yi on a Wuhan ICU was read more than 100,000 times on WeChat. But in June 2021 it also shuttered, unable to pay its bills in a plummeting market for digital media advertising.

Where else to go, but home? Yi grew up in Zigong, a rust-belt city of 2.5 million in Sichuan, known for its centuries-old salt wells. Ten kilometers downstream lies Xianshi, a town of less than 40,000. Historically, merchant boats carrying Zigong salt eastward would have passed through its docks before reaching the Yangtze river.

This is the “Salt Town” that Yi lived in for 18 months, speaking the local dialect and scrutinizing the town’s most intimate business, focusing on the lives of its women. “Life in Salt Town is a series of tiny cuts and open wounds,” she writes in the book’s conclusion. “Women are trying to stanch the bleeding, while men are adding salt to the wounds.”

Xianshi, according to Yi, is poor and picturesque. Her color photographs, inserted in clusters throughout the book, show stone-laid walkways, strings of sausages hanging in the sun, and rapeseed blooming bright yellow among traditional gray-and-white homes. Out of the nearly hundred local residents Yi interviewed, for the ten chosen protagonists she supplements their tales with reporting and archival research.

For Yi’s readers in Chinese megalopolises, Xianshi is presented as more foreign than Barcelona or New York. The town operates on a wholly different sense of time than in urban China: life here, according to Yi, is caught between pessimistic inertia and a romanticized languor.

This is embodied in the story of nonagenarian Grandma Chen Bingzhi, in the first chapter. Chen, born in 1932, survived multiple famines and had six children. She ran a brothel in Xianshi from the mid-90s until 2019, when she was convicted of organized prostitution. After two years serving a community-based sentence on account of her age, she now runs a corner store in Xianshi. Yet despite Chen’s tenacity, Yi writes of her in a patronizing tone, as if she is entirely stuck in the past:

Inside Chen Bingzhi’s memory trove, there is only Chairman Mao; she doesn’t know who the current President is. … She has never spent a single day in school and doesn’t know [the correct term for] the Cultural Revolution. … She doesn’t know Ruan Lingyu or Teresa Teng [popular celebrities from the 1930s and 1970s]. The only song she knows by heart is ‘The East is red, the sun rises, from China comes Mao Zedong.‘

Interwoven through the ten profiles are themes that define rural womanhood: discrimination, domestic violence, family duty and resilient entrepreneurship. The front line of this gender war is in the home. Every woman profiled in Salt Town mentions being beaten by their husbands. To them, being on the receiving end of domestic violence is as prosaic as laundry; it’s simply what men do.

Wang Guanhua, in chapter two, has it the worst. Born in 1959, she married the cotton fluffer Sun at age 22. Sun was repeatedly unfaithful, and nearly killed Wang twice during fits of rage. They divorced in 2004, but remarried in 2020 as Wang found the shame and loneliness of being a divorcee unbearable. Yi describes the brutality:

Wang was thirty-six, and it had been fourteen years since she married Sun the Cotton Guy. She didn’t know that this is called ‘domestic violence’ or that it is illegal. That was the first time she felt fear in her life: ‘He beat me with his fists, and stepped on me with his feet, and I thought I was about to die.’

The journalist’s fixation on the correct language here rings hollow. Knowing the right words only matters if there is someone who listens. Wang, who was repeatedly failed by her local government and community when she complained, comes up against nothing but silence.

A scroll through Douban shows that many readers found Wang, Grandma Chen and the entrepreneurial “boss lady” Li Suqin of chapter three unforgettable, but the other seven protagonists repetitive. It’s absent dad after absent dad, misfortune after misfortune, beating after beating. Tedium is, perhaps, the point. Abuse seeks to make its victims small. To encounter it again and again, from every male authority, shrinks one’s sense of self until there is none. Salt Town’s poignance emerges when its narrative form, loosely woven around generous quotations, closes in on the social tragedy that is misogyny.

To rural women, being on the receiving end of domestic violence is as prosaic as laundry; it’s simply what men do

At its best, Salt Town strikes at the nexus of nation and gender. Wang Guanhua’s mother-in-law is loyal to the cult of male superiority, seeing her daughter-in-law’s suffering as collateral damage. National policy is happy to accommodate: China’s first anti-domestic violence law only went into effect in 2016.

Even birth was a concession for rural women, not a right. One-and-a-half kids, a chillingly-named exception to the One Child policy, permitted rural families whose firstborn was female to have another child in order to try for a boy. In 1985, Wang herself was forced to have an abortion by Xianshi’s family planning committee. Yi quotes Wang’s description of the horror:

‘The doctor saw that the [induced] child was still alive, so he put something in his mouth, and then he was dead.’ … The doctor threw the dead baby into a bucket. Wang’s mother-in-law, just then arriving after having heard the news, did not take a single look at Wang, but kept crying in the direction of the plastic bucket. ‘It was a boy, it was a boy…’

In Xianshi, generation after generation is sacrificed at the altar of maintaining male bloodlines. Yet it’s not enough to note gender discrimination without offering any explanation of its root causes, or to delve deeper into the disparity between countryside and city. Xianshi, after all, is only a thirty-minute drive from the industrial city of Zigong where Yi grew up. So why does it feel like another world? Portrayals of Xianshi’s isolation in Salt Town, though poignant, fail to answer more interesting questions of why urban feminist osmosis failed to reach here.

Instead, the journalist seems overly preoccupied with her own position in the middle of it all. In a note under one photograph of the town’s landscape, studded with tiled roofs and yellow rapeseed blossoms, she writes:

They have lived inside this painting for generations, and their own hard work has built up parts of this very painting, yet I suspect they’ve never had the time or emotional bandwidth to appreciate their own home like I do.

As if interiority is the exclusive realm of a city arrival. Instead of investigating the glaring systematic ills their experiences hint at, Yi seems largely content with treating her subject’s stories as abstractions of oppression. One wonders about unexplored details. Why does Xianshi’s branch of the All-China Women’s Federation require “visible wounds” to establish domestic violence, as Yi quotes them saying? Since many girls in Xianshi drop out of middle school, what do teachers do when their female students stop showing up? At worst, Yi’s plainspoken storytelling seems to normalize her interviewees’ suffering, as if action is always futile.

In the book’s introduction, Yi laments: “Even today, as we preach women’s rights in the 21st century in Beijing and Shanghai, [the women of Xianshi] are still moving through the cyclical patterns of ancient history.” Ancient history it is not: rural Chinese women’s economic dispossession, borne of patrilineal land inheritance practices, continues due to weak legal protection and an indifferent bureaucracy. Feminists in the country are advocating for amendments to the Rural Collective Economic Organizations Law, which would ensure equal land inheritance rights for rural women regardless of marital or reproductive status.

Salt Town, focused on empathizing with the victims, forgets to expose the assailants

In a March interview, Yi told The Paper, a Shanghai-based digital newspaper, that she doesn’t consider Salt Town a feminist work. “This is not a book meant to incite gender opposition,” she said. Nonfiction, of course, need not be activism. Yet Yi’s reluctance to acknowledge the existence of feminist opposition — to make clear, at least, that women and their oppressors have conflicting interests — leads to omission.

In a Chinese media landscape increasingly hostile to feminists, and with state organs intent on stamping out grassroots activism, it makes sense that Yi has steered on the side of caution. But at times, her wariness gives way to vacuous analysis. Salt Town’s tenth and final chapter concerns Huang Xinyi, a 17-year-old hostess and sex worker at a local karaoke. The only Gen-Z protagonist of the book is in the same illicit industry that Grandma Chen worked in. In the epilogue, Yi addresses this connection: “The fact that a gray-haired 90-year-old grandmother and a 17-year-old blossoming teen are in the same ‘naked business’ evokes a kind of shared, tragic sense of fatalism.” But to abstract this fact as fatalism is to erase the men who pay to abuse her, the family which neglects her, and the economic stagnation that leaves under-educated women behind. Salt Town, focused on empathizing with the victims, forgets to expose the assailants.

Rural Chinese women live with deep intergenerational trauma from centuries of deprivation and state violence, with few guarantees of institutional protection. They still struggle to move upward in a stubbornly discriminatory society all too happy to exploit their labor. While tackling the topic is commendable, in Salt Town the big-city writer looks at the small town the same way we look at this history today — from a safe distance. What hurts Xianshi’s women is still at large. ∎

Header: The township of Xianshi, Sichuan. All photos courtesy of New Star Press.

Irene Zhang is a Master’s candidate studying Chinese politics at Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies. She is Chinese-Canadian from Vancouver, and was previously a fellow and research scholar at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.