Reviewed: Chinese History: A New Manual, Endymion Wilkinson (Harvard University Press, 2022)

When did a Chinese eunuch celebrate his birthday?

On the anniversary of his castration, the beginning of his new life.

How many drum beats announced the end of curfew in a Tang dynasty city?

3,000.

Today, the pass that separates Guangxi from Vietnam is called “Friendship Pass.” What was it called in the Han dynasty?

“Controlling the Barbarians Pass.”

When did Sichuanese cooking develop into its “mala” numb and spicy form?

Only a century ago. The peppers arrived from Hunan province in the late 18th century, and at first were only used for decoration.

As any graduate student of Chinese history knows, there is one book in the world which is most likely to answer almost any question on China imaginable, such as the above (as indeed it does). That tome is Chinese History: A New Manual by Endymion Wilkinson.

First published in 1973, the manual was originally titled The History of Imperial China: A Research Guide. It was 70,000 words long, with 219 pages and weighed 15.5 ounces. By 2013, the fourth edition of “the Wilkinson” — as those in the know referred to it, irregardless of its new title — was 1,148 pages long and weighed 5.75 pounds. The 50th anniversary sixth edition, published last year by the Harvard University Asia Center, is divided into two volumes, clocking in at a total of 2,152 pages and weighing just under 10 pounds. Between the covers are 1.75 million words — 25 times longer than the original.

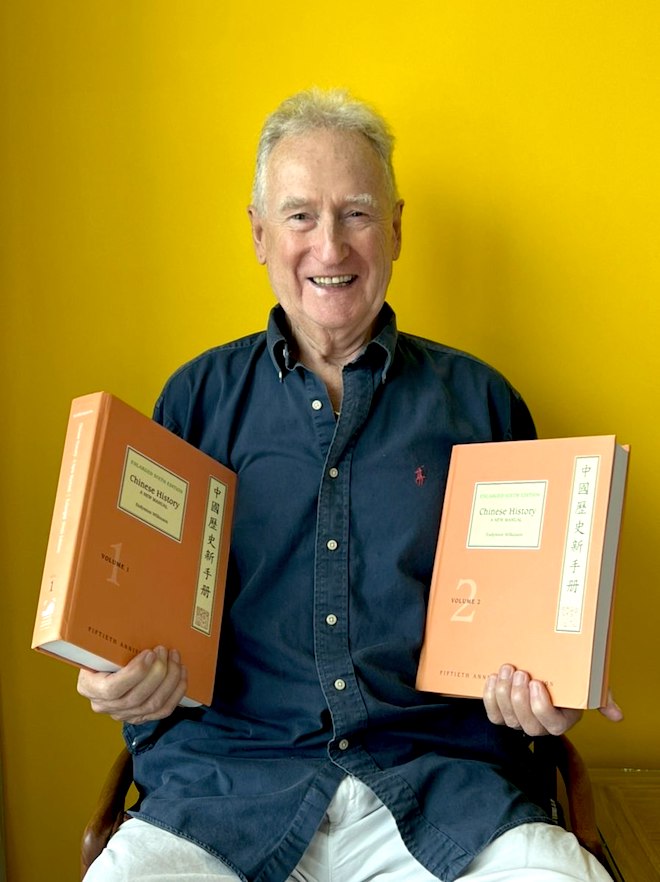

“Had I known the amount of work it required, I would not have touched it with a barge pole,” Wilkinson told me in an interview from a small fishing village on the eastern coast of Thailand, where he has retired.

The manual is divided into a panoply of short sections, discussing miscellaneous topics ranging from scholars banished to Guangdong (they kvetch about Cantonese food) to classical urban curfews (announced by drums, trumpets and cannons; to be outside after hours you had to carry an official lantern). The four pages dedicated to the discussion of birthdays, for example, notes that in ancient China, birthdays were not celebrated (according to 17th century philologist Gu Yanwu: “The birthday ritual, this is not something that the ancients had” 生日之禮古人所無). Rather, the concept emerged with the development of Buddhism, the first appearance being a reference in the third century CE to a celebration of the Buddha’s birthday. The most dangerous birthdays were seen to be multiples of nine, plus the 73rd and 84th birthdays — possibly because these were the ages that Confucius and Mencius died, by Wilkinson’s account.

356 boxes dapple the text, providing even more obscure factoids. Box 115, for instance, describes the Tang dynasty board game Struggling to Advance in Office, later reprised in the Qing dynasty, where players throw dice to advance through the Chinese civil bureaucracy. (Each of the thousand roles listed on the board is divided into two grades. Players who roll a pair of sixes are recognized for their talent; rolling two ones means they are demoted for corruption.)

These minutiae combine into a monument of scholarship, one of the great works on China published in English (or any other language) in the last hundred years. In 2000, the veteran China scholar Roland Suleski reviewed the book, writing: “There are numerous points that distinguish this manual as a work of the first rank, a collection that will be utilized and referenced by scholars for decades to come.” Talking to me 23 years later, from Suffolk University in Boston, Suleski called the manual “so important it is hard for me to imagine a scholar who could say it is not worth it. I can’t imagine it.”

Had I known the amount of work it required, I would not have touched it with a barge pole.

Endymion Wilkinson

For Endymion Porter Wilkinson, born in 1941 in Lewes, England, the book was as much a product of serendipity as was his career in China studies. As an undergraduate student at King’s College, Cambridge, just as he was getting bored with the History faculty’s Eurocentric teaching of British history, which was familiar from his boarding school at Gordonstoun, he happened upon a 1959 book about Chinese, Mandarin Textbook (汉语教科书). Soon, his obsession with China began, and he completed a double degree in history and oriental studies.

On graduating, Wilkinson taught English in China from August 1964 to August 1966, at the Peking Language Institute (today’s Beijing Language University). He was among the few foreigners allowed into the country at the time — part of Zhou Enlai’s effort to reintegrate China into the wider world beyond the USSR — and was hired to teach due to his “model accent.” His contract ended just after the Cultural Revolution broke out (upon which he was barred from eating in the Institute dining hall), and he was forced to leave. After submitting his PhD dissertation at Princeton some years later, Wilkinson took a teaching job at SOAS, University of London, and began drafting a series of notes on Chinese history. It was these notes that grew into the manual.

Initially, Wilkinson did not see the manual as publishable — and nor did his peers. When W.G. Beasley, chairman of the history department at SOAS, heard about the idea, he was flabbergasted. According to Wilkinson, Beasley said that reading another man’s notes was analogous to “using another man’s toothbrush at a conference.” But the dean of China studies at Harvard University, John King Fairbank, was impressed by the notes and in 1971 urged John Bishop, the head of the Harvard-Yenching Institute, to publish them. Bishop was less enthused, telling Wilkinson that it would take five to ten years to get the notes into a publishable form. According to Wilkinson: “Fairbank said, ‘To hell with the Harvard-Yenching Institute. We’ll publish it next year.’ ” In 1973, they did so.

The manual is the closest thing in any language (arguably including Chinese) to being an encyclopedia of Chinese history. Professor Diana Lary, who was a colleague of Wilkinson in Beijing in the 1960s, told me: “There is no scholarly project on that scale at the moment that I know of,” she said, including in China. “In the manual, there is very clear production of knowledge on every page.”

After its publication, Wilkinson left academia to work as an EU diplomat in Southeast Asia and Japan, before becoming the EU’s ambassador to Beijing from 1994 to 2001, where he helped negotiate China’s entry into the WTO. “That was a hell of a job,” as he put it.

Wilkinson’s workaholism borders on masochism. During the middle of his ambassadorship, Harvard University Press asked him to produce a new edition of the manual. Instead of politely declining the invitation due to his work commitments, he threw himself into the task, waking up early to work on revisions. “He would work on the book everyday,” said Professor Lary, “either early in the morning or late at night. You cannot imagine the hours he put into it. He had a very demanding day job, lots of tension, lots of meetings. And then the manual. It sort of grounded him, kept him doing this very meticulous work.”

In 2016, Peking University Press published a three-volume Chinese edition of the manual. “I was very pleased with that,” he said. More than 13,000 copies were sold, and the Shanghai newspaper Wenhui Daily published an eight-page special supplement on him. Yet the Chinese publisher censored parts of the manual, including any seemingly negative detail about a Chinese leader — such as an anecdote about Li Xiannian, China’s president from 1983 to 1988 under Deng Xiaoping, forgetting the fourth of the Four Modernizations. On several occasions, the head of the translation team asked if it was okay to cut a particular passage. Wilkinson usually agreed: “So long as they published 99.9% of it, I was fine with it.”

Another sticking point was a matter of ethnonationalism. In the English versions of the manual, Wilkinson describes the Liao Dynasty as founded by a non-Chinese ethnicity, the Khitans. The Chinese edition brings this discussion in line with Party orthodoxy, referring to the Khitans as a “national minority” — that is, framing the Khitans not as outsiders but as a member of the Chinese family of ethnic groups. “In the end, I gave way,” Wilkinson said, adding “these are the perils of writing Chinese history.”

What is the future of the manual? “The sixth edition will be the last print edition,” Wilkinson confirmed. “We cannot go on publishing print editions. You can’t take it on an airplane.” Instead, updated versions of the manual can be downloaded on the Chinese dictionary app, Pleco.

“I have given the e-rights to Pleco,” the author told me. “I am 82 now, and I will not survive all that much longer, and [Pleco] has efficiently published updated digital editions at a reasonable price since 2018.” It seems assured that, in one form or another, Wilkinson’s scholarship will endure for years to come. As Professor Suleski summed up: “The manual is Endymion’s contribution to mankind.” ∎

Header image: “Biographies of Lian Pou and Lin Xiangru,” a scroll detailing the rivalry between two Song generals by 11th century dynasty calligrapher Huang Tingjian (public domain).

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated digital rights to the manual had been given to Harvard. This had subsequently changed.

Lee Moore is a journalist and adjunct professor teaching Chinese and Taiwanese literature and film at the University of Oregon. He is also writing a book, China’s Backstory: The Literature and History Behind Today’s Front-Page China News.