In Beijing, scrolling through the social media app WeChat, I lingered on a post from Zhazha (literally “Boom Boom”) — an ebullient, thirty-something Chinese photographer I hadn’t seen in a while. He had felt burnt out by the city, and had moved to a rural village in Dali, a far-flung corner of southwest China. Flipping through images of his new digs, I wished I had too. His farmhouse had a cobbled yard: grass poking between the cracks, foliage-fringed, with a Taoist yin-yang formed from pebbles, next to a persimmon tree and a reading bench. The house itself had old wooden beams, and a skylight boasting a view of the three ancient pagodas Dali was famous for, with towering mountains as their backdrop.

From my city apartment, it looked like heaven — space to think and breathe, away from the smog and the honk and the hurry. Zhazha bought vegetables from his village market, grown in fields nearby; he spent long, lazy days hiking up to hidden waterfalls in the hillside; he focused on creative projects, without having to worry about rent or living costs. Later, I asked him why he had left Beijing.

“Beijing used to be very fun,” he said, “but it’s difficult to live in and to earn enough money, so I didn’t like it. I discovered actually I wasn’t happy. So I migrated to Dali in order to find a new way of life.”

Finding a new way of life was a quest I began to hear a lot. In China, city malaise was writ large by the nation’s sheer scale and pace of urbanization. They talked of it as “city sickness.” In the space of forty years since the 1980s, China had squeezed in the industrialization and economic growth that Western countries had taken centuries to achieve. But now its citizens were stepping back to ask: What was it all for? I’m richer, but am I happy? After economic and career development, what about personal development?

A new buzzword was starting to appear online: “involution.” The Chinese, neijuan, literally means to be “rolled up inside.” If you worked twelve hours a day, then you were “rolled up” by overwork culture. If you were a student whose parents jam-packed your weekend with back-to-back extracurricular and exam-prep classes, then you were “rolled up” by the education system. If you were commuting for two hours to pay off a shoebox apartment and buy a car so you could attract a wife, you were “rolled up” by social conventions. Jack Ma, then China’s richest man, praised “996” work hours — 9 am to 9 pm, six days a week — as a “blessing” (for his bottom line, at least). But bloodsucking capitalism had begun to clot. It was the rat race, the hamster wheel, and the rodents were revolting.

Why should I work so hard, they thought, when I’m just running to stand still? The best jobs were taken, the pie already divided up. In today’s China, it was difficult to move ahead and easy to fall behind. One blog post likened neijuan to the prisoner’s dilemma, using an image of a concert where those in the front rows stood up to get a better view. If everyone sat, the view would be the same — but because some were standing, everyone behind them had to as well. Not social evolution, but involution.

A solution was proposed: instead of standing or sitting, lie down. The word used for this, tangping, literally meant to “lie flat” but signalled a deeper opting out of the system. If the game was rigged and social mobility impossible, why even bother? Quit the rat race; sleep in instead of working late; break the cycle. The most extreme form was to escape the city altogether — that hub we had gravitated towards in search of opportunity, only to be disenchanted. That was what Zhazha had done, fleeing to country climes. The rural environment of Dali in south-west China was already jokingly dubbed the “capital of lying flat.” Others called it “Dalifornia,” for its good weather and chill vibes.

China had squeezed in the economic growth that Western countries had taken centuries to achieve. But now its citizens were stepping back to ask: What was it all for? I’m richer, but am I happy?

This back-to-the-land trend was a direct reversal of everything upwardly mobile Chinese people used to hold dear. For decades, those born in the countryside had wanted only to escape its poverty. Now, since 2011, more people lived in urban than rural areas. Yet for the generations born in China’s mega-cities, some wanted to get out — to return to the soil where their forefathers had come from. Instead of chasing bright lights in the big city, they dreamt of open farmland and the quiet life. After forty years of urbanisation, the flow was reversing.

It was still a minority who were privileged, or crazy, enough to quit their city jobs. Some were the enriched middle class, seeking a patch of sun to lie in, equivalent to a Londoner’s cottage in Tuscany or a lake-house in upstate New York. Others were penniless urban workers who wanted to drop off the grid and reinvent themselves entirely. Either way, this inverse migration from city to country, once a trickle, was becoming a stream. Zhazha was an avatar for the trend: a thirty-something creative professional fed up with the city, who wanted to live his own life instead of someone else’s expectations of what that should be.

“My parents’ generation worked hard all of their lives to leave the countryside and move to a township so I could have better opportunities,” he told me. “They didn’t understand why I would go back to the countryside.” His father, a carpenter from rural Shandong province, had been overjoyed when his son went to Beijing, the first in the family to attend university. While he had hoped Zhazha might work in a bank or state company, he would still brag to neighbours that his son was a photographer not a farmer. It was only a matter of time, surely, before Zhazha would marry, buy a flat, and make good on the urban dream.

When his son moved to Dali, thirty-five and still unmarried, Zhazha’s dad was at a loss. When he was young himself, Zhazha’s grandfather — a subsistence farmer — would grow vegetables just so the family had enough to eat. All he and his wife had wanted was for their son to escape that life of toil. But now his son was living in a countryside farmhouse, sending pictures of his vegetable patch as if it was something to be proud of! “It’s very simple,” explained Zhazha. “They think I’m a failure.”

It had taken just two generations for a Chinese family to pass from pre-industrial agrarianism to post-material urban malaise — for the grandchild of farmers to return to the land.

“I just think there’s more to life than what everyone expects you to do,” Zhazha said. “To have a job and a car and a house and earn lots of money.” His unease was a refraction of China’s story at large, where worshipping at the font of economic development had left a spiritual vacuum at the nation’s heart. What now? What next? Am I happy?

“That’s why I really left Beijing,” Zhazha added. “It’s not just the traffic and how expensive everything was — everyone complains about that. I wanted a quieter life where I can do what I want to do and find out who I really am.”

The mountain valley of Dali that he chose for his escape seemed the epitome of that new life. Antithesis of involution. Capital of lying flat. Dalifornia. It spoke a promise of escape and change for a disillusioned generation — and in the mire of my own malaise, it held an allure that was difficult to resist.

It had taken just two generations for a Chinese family to pass from pre-industrial agrarianism to post-material urban malaise.

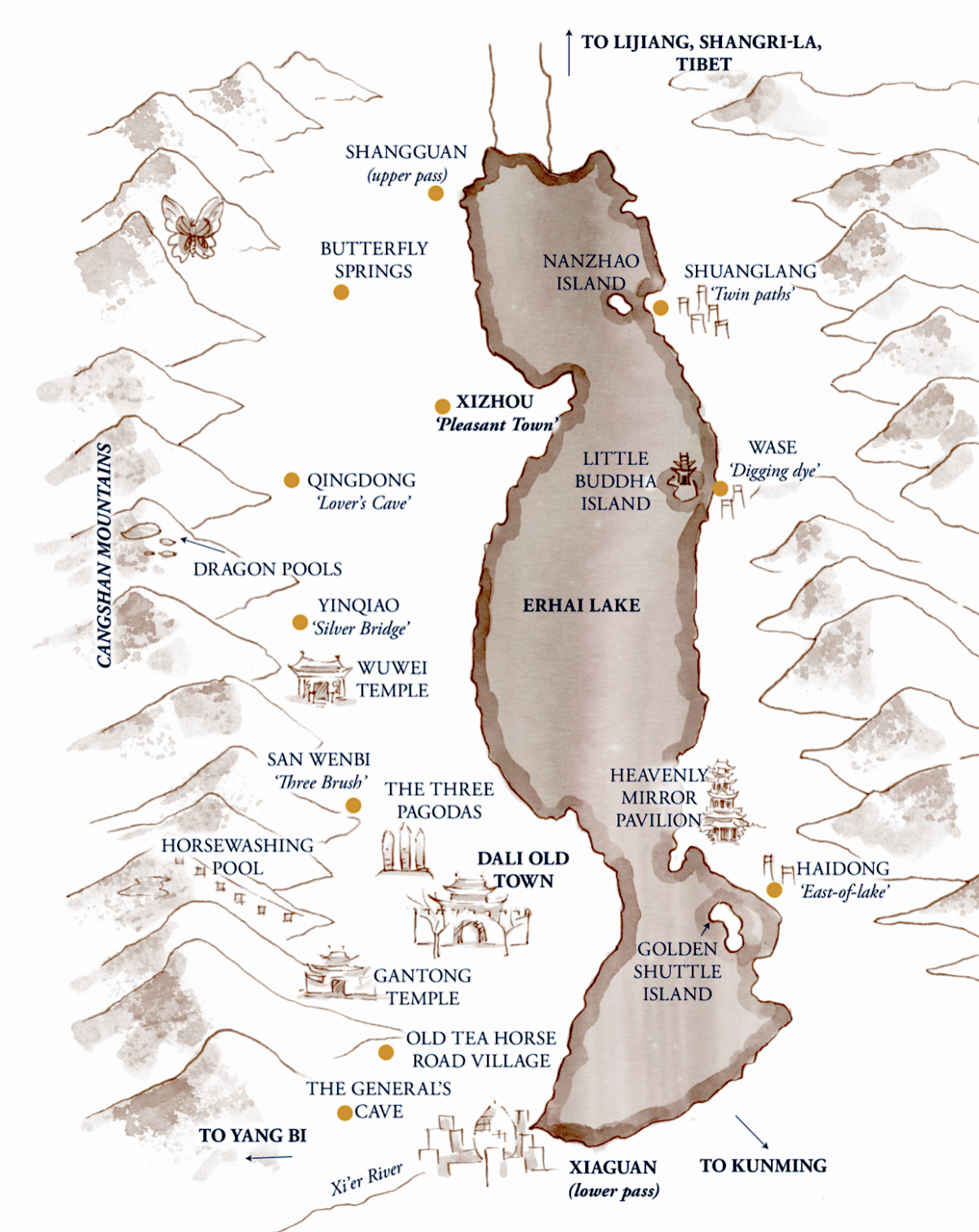

Tucked away in the highlands of Yunnan province, south-west China, Dali sits in a fold of the Hengduan mountain range, which rises westward to become the Himalayas. At an elevation of 2,000 metres, the terrain keeps climbing until the border of Tibet, 300 kilometres north-west. Myanmar is half that distance away, and Laos a little further to the south-east. Nestled into these hills of South-East Asia, in antiquity Dali was a trading post on the southern Silk Road — shifting jade, ivory and spices — and along the ancient Tea Horse Road that connected the tea terraces of Pu’er to the Tibetan plateau. Until a century ago this was at the heart of what scholars term “Zomia,” the ungovernable mountainous zone between nations. It is a good place to hide in.

The valley itself was formed some fifty million years ago, when the Indian and Eurasian plates collided. Ripples from that tectonic kiss crumpled the earth all the way from the heights of Everest down into Yunnan. One of those ripples is the Cangshan massif, a stretch of mountainside that overlooks Dali from the west. 4,122 metres at its highest point and extending forty-four kilometres, the Cang mountains (pronounced “tsang”) comprise nineteen peaks, snow-capped in winter, with eighteen gorges between them — cut into the earth by glacial erosion — whose swift streams trickle down from the top. An evergreen conifer forest of pine, fir, and spruce coats the range, giving Cangshan its name: the Verdant Mountains.

Those eighteen streams feed into the lake of Erhai (pronounced “arr-hi”), which sits squat in the centre of the valley, forty kilometres long and shaped like an ear. Er is a homophone for “ear” in Chinese, while hai technically means “sea,” so named by Mongolian invaders who hadn’t seen an expanse of water so large. Its waters bleed out into the upper Mekong, which runs south — parallel with the Salween and Yangtze from their sources in Tibet — until those three great rivers of Asia, travel companions for this stretch of their journey, part ways. The fresh water and plentiful fish of Lake Er were the lifeblood of Dali for millennia, with settlements rising by its shores and a tradition of cormorant fishing.

The Chinese saying “to have mountains and water” describes an ideal place of natural beauty, peaceful and remote with balanced fengshui. Dali has both. Most residents of the valley live on the western bank of the lake, where the terrain slopes gently down from the foothills of the mountains to the lapping shore. At the southern tip of the lake is the larger town of Xiaguan, the “lower pass” — so named for when the mountain passes into the valley were heavily fortified. At Lake Er’s northern end is the less built-up “upper pass.” In between are villages and farmland, with no buildings permitted higher than three storeys.

Halfway between the lower and upper passes is Dali’s famous Old Town. Once capital of an ancient kingdom, later a Ming fortress, its thick walls once enclosed four square kilometres of cobbled lanes, with hulking arched gates at each compass point. Now all but the western and southern walls have been torn down, and more streets are paved than cobbled, though the gates remain. Yet the stone homes, curving roofs and leafy courtyards that speckle its labyrinthine ways still give the Old Town charm, while just outside the walls to its north-west the three ancient pagodas cast their long shadows, relics of a bygone age.

The locals of Dali are an ethnic minority called the Bai people. The province of Yunnan is home to twenty-five of China’s fifty-five minorities; further up in its highlands are the hill-tribe Yi, the shamanistic Naxi, the matrilineal Mosuo and the Buddhist Tibetans. Bai literally means “white,” named for the moon-coloured furs of their ceremonial headdress, though their everyday clothes are mostly blue. With their own topolect (but no written script), religion (folk-deity worship) and festivals (chiefly Torch Festival at the end of summer), the Bai were culturally a world apart from China’s Han majority. Long before migrants from the outside arrived in the valley, Dali was theirs alone.

These city arrivals in the countryside were dubbed fanxiang qingnian, or “returning youth.” Some called themselves xinyimin — the “new migrants.”

No more. Once an independent kingdom, Dali fended off invasion by the Tang dynasty but fell to the Mongols in the 13th century, and was later folded into the Ming Chinese state. Han migrants settled in the valley, as well as Hui Muslims and other groups. The Bai people sinicized, incorporating Chinese customs into the fabric of their everyday life. Yet they were still far enough from the centre of the Chinese state to be left alone, hidden in the remote poverty of their otherwise idyllic valley.

Over the last few decades, Dali has attracted a new kind of outsider. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was a rare traveller who stumbled into the valley. Back then, the Old Town and surrounding villages were undeveloped, with dirt tracks, farmland and crumbling houses. The same mountains that made Dali picturesque kept it poor, obstructing the modernisation that came first to China’s eastern seaboard. Yet this was what the travellers were looking for: a rustic escape from explosive urbanisation, and a refuge from the politics of the cities — including for dissidents who fled here after the Tiananmen crackdown, such as the poet Liao Yiwu who lived there in the early 2000s.

By the new millennium, Dali had also become a go-to destination for the in-the-know backpacker, a northern extension of the banana-pancake trail through South-East Asia. Part of the appeal was that marijuana grew wild in Dali’s hills (and still does). It was an easy place to get high, in both senses of the word. In those days, local Bai grannies would sit along the main strip of the Old Town — dubbed “Foreigner Street” for all the Western backpackers — and hawk their self-picked wares at passing foreigners in broken English: “Ganja, ganja?” This continued until local police cottoned on that the plant had uses besides twining into rope and chewing its seeds, and told the grannies to stop pushing.

Some travellers who came to Dali never left. Arrivals from Chinese cities rented stone houses in the Old Town, for as little as a few thousand yuan a year. A Taiwanese hippy community settled into what became known as “Taiwan village.” Two Americans opened a café called Salvador’s (after ‘the other Dali’), next to a few dive bars — Bad Monkey, Bird Bar, Lizard — serving those outsiders who had made Dali their home. They were the best kind of layabouts: living cheap in courtyard homes, sampling the local herbs, taking it easy and hoping their secret paradise wouldn’t be discovered.

Yet discovered it was. Already the town of Lijiang to the north had touristified, rebuilt after an earthquake in 1996. It took Dali’s government longer to catch up to the commercial prospects of its natural beauty, but in the mid-2010s the Old Town was renovated, rents were hiked, souvenir shops set up stall, and the hippies moved out to surrounding villages. Dali was back on the map. It became a trendy escape from the hubbub of the cities, for both tourists seeking a temporary break and reverse migrants looking to reinvent themselves.

In 2014, Chinese folk singer Hao Yun penned a hit song that captured the zeitgeist: “Go to Dali.” He sang:

Are you unhappy in life?

Haven’t laughed for a long time and don’t know why?

Go to Dali! Go to Dali!

If you’re not happy and you don’t like it here,

Why not head west, all the way to Dali?

These city arrivals in the countryside were dubbed fanxiang qingnian, or “returning youth,” although every generation was represented. Some called themselves xinyimin — the “new migrants.” Others used a simpler term: “new Dali people.”

Some old-time new migrants complained that Dali was changing, commercializing. But that change was inevitable, now that the valley had been “discovered” all over again. And it was change that those who moved here sought above all else. A new way of life. A new home. A new perspective. And when the sea change crashes over us, we must find the readiness to be swept by its tides, lest we drown in brittle resistance. ∎

Excerpted from The Mountains Are High, by Alec Ash, published by Scribe (February, 2024). A book launch and talk will be held at Asia Society in New York on March 11, register here.

Alec Ash is a writer focused on China, and editor of China Books Review. He is the author of Wish Lanterns (2016), following the lives of young Chinese in Beijing, and The Mountains Are High (2024) about city escapees in Dali, Yunnan. His articles have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic and elsewhere. Born and educated in Oxford, England, he lived in China from 2008-2022, and is now based in New York.