Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed:

• China’s Law of the Sea: The New Rules of Maritime Order, Isaac B. Kardon (Yale University Press, 2023)

• On Dangerous Ground: America’s Century in the South China Sea, Gregory B. Poling (Oxford University Press, 2022)

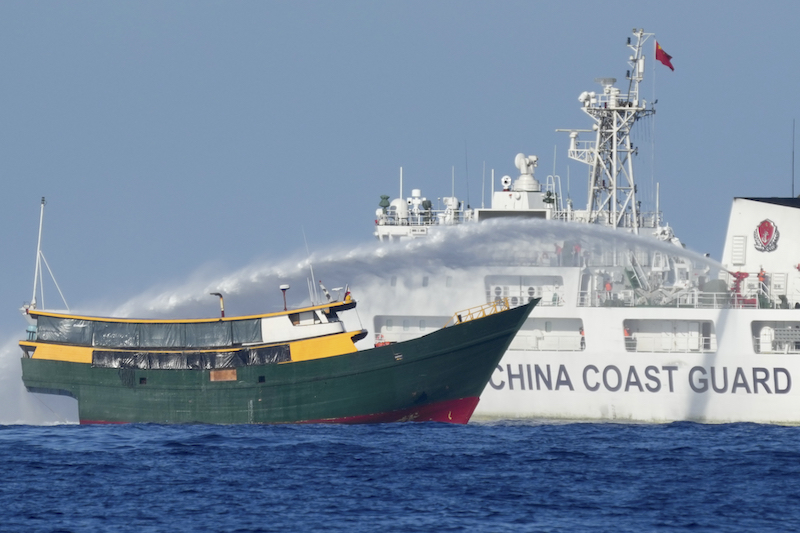

Last December, China and the Philippines found themselves embroiled in yet another standoff in the South China Sea. This time, the dispute was over a submerged reef, the Second Thomas Shoal, less than 200 nautical miles from the Philippines island of Palawan. Manila accused Beijing of repelling their attempt to resupply a handful of marines stationed on a rusted navy ship, the BRP Sierra Madre, which the Philippines had deliberately ran aground decades ago to bolster control of the reef. Video evidence, uploaded in real-time on social media, showed Chinese coast guard and maritime militia vessels swarming the Philippines’ resupply boat, firing water cannons and deliberately ramming Philippine coast guard ships in the vicinity.

This modern-day David and Goliath confrontation is about much more than rocks and ramming. It is a microcosm of China’s ambition to reshape a new maritime order in the Asia-Pacific. This desired order is Westphalian in nature, and in the attempt to achieve it, laws, norms and practices are taking a backseat to bare-knuckle power politics.

The source of the tension is Beijing’s sovereignty claims in the South China Sea. Many other claimants also assert large swaths of territory there, yet only China has drawn a circle around the entire body of water and claimed everything as its own. The infamous “nine-dash line” — a map of the sea with nine lines cutting into the exclusive economic zones of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia — has riled China’s neighbors in Southeast Asia. Despite having no legal basis (the nine-dash line was struck down by a 2016 Hague tribunal) China has asserted sovereignty over virtually all the islands, rocks and underwater features, as well as the oil and gas, within this line.

Why, after decades of tension and conflict, has China stuck so stridently to these claims?

This modern-day David and Goliath confrontation is a microcosm of China’s ambition to reshape a new maritime order in the Asia-Pacific.

Two new books shed light on this question: China’s Law of the Sea: The New Rules of Maritime Order by Isaac B. Kardon and On Dangerous Ground: America’s Century in the South China Sea by Gregory B. Poling. The authors, both China analysts at think tanks in Washington D.C., tackle a complex topic with analytical precision, and one conclusion is clear: China is essentially taking a large geopolitical gamble that a new maritime order will be formed around Beijing’s interests — and that in order to preserve peace, others in the region should accommodate China’s sovereignty, navigational rights and control of resources in the South China Sea.

This battle is not just over whose territorial and maritime claims will prevail; it is about whose concept of maritime rights prevails. The outcome will have major ramifications for the world order. In short, what is at stake is nothing less than the future international maritime order in Asia and beyond. No other country will exert more influence over the trajectory of such a “rules-based order” than China — a country largely left out of the postwar rule-making order, which is now the world’s second-largest economy and moving closer to a realpolitik Westphalian system where might makes right and sovereignty trumps international norms.

Both authors fall short of concluding that China is attempting a complete reordering of maritime Asia. Instead they lay out, in minute detail, how Beijing is methodically attempting to undermine, water down and otherwise render meaningless the principles that have shaped that rules-based maritime order for decades. China, they argue, perceives international law not as something to be upheld, but rather as something to be adapted to accommodate China’s unique interests and rise. This presents a problem not only for claimants to territory in the South China Sea, but also to other major powers, including the U.S., who have a stake in the free flow of commerce and freedom of navigation.

One law in particular forms the centerpiece of their analysis: the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNLOS). This law is widely considered as the rules of the road for what states can and cannot do in the ocean, including what resources (such as fish, oil and natural gas) can be exploited and by whom. While China and most other countries are signatories to UNCLOS (the U.S. has signed but not ratified it), Kardon and Poling describe how China is attempting to hollow out the core tenets of UNCLOS, using it as a political tool to assert controversial rights and claims that benefit Beijing, while ignoring or discounting others.

Other nations are starting to push back. And China is digging in its heels.

China is essentially taking a large geopolitical gamble that a new maritime order will be shaped and formed around Beijing’s interests.

In China’s Law of the Sea, Isaac Kardon details how Beijing’s efforts to prosecute its many disputes are “perhaps the clearest and most widely recognized case of the PRC’s rising power and ambition coming into conflict with international order.” He quotes China’s top former diplomat, Yang Jiechi, as saying that altering the maritime order is a primary object of the nation’s mission to “actively take part in revising existing international rules and setting new rules.”

Kardon, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and former assistant professor at the U.S. Naval War College, uses the South China Sea as a case study to examine these broader ambitions. “There are significant reasons to regard China’s influence on the law of the sea as a leading indicator of its putative challenge to order,” he writes. “In the law of the sea, as in several other important domains, China has straightforwardly announced an intention to change the rules.”

Yet, rather than wanting to tear up the existing order, China is content with reshaping it. Sifting through the voluminous legal and political texts written on the subject by Chinese academics and strategists, Kardon documents how the law of the sea has been “internalized” into China’s system and “transformed in line with a clear political intent to assert legality of controversial and sometimes indeterminate PRC claims.” He finds, paradoxically:

Far from disregarding international law in its maritime disputes, Beijing regards law as essential. Systematically, deliberately, and with growing sophistication, China’s leaders seek to shape and use international law to their advantage. … Operations on the water are undertaken expressly to advance China’s definitions of “the rules” through actions portrayed as defending China’s rights under international law.

Kardon concludes that Chinese officials define their practices in terms of China’s maritime law, “framed in explicitly legal terms, implemented by domestic agents empowered by a domestic legal code that purports to uphold the law of the sea, but in service of the party-state’s maritime objectives.” In short, Beijing takes an à la carte approach to the rules. Choose the aspects that fit your needs. Ignore or redefine those that don’t.

Like Poling, Kardon finds that China’s neighbors are actively pushing back against its claims in the South China Sea. But the deployment of hard power from China’s navy, coast guard and maritime militia is preventing its neighbors from fishing or drilling for oil in their own waters. “China has exercised what amounts to ‘veto jurisdiction’ over [fishing and] the exploitation of oil and gas disputed zones,” he writes. “Even if these claims are not fully implemented or realized, the effectiveness of UNCLOS resource rules is damaged when the rights they prescribe cannot be exercised in actuality.”

Beijing takes an à la carte approach to the rules. Choose the aspects that fit your needs. Ignore or redefine those that don’t.

Greg Poling’s On Dangerous Ground approaches China’s challenge to the maritime order from the perspective of another major actor: the United States. Poling is a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), where he directs the Southeast Asia Program. A serious but readable academic study, the book draws on minutes, notes, memos and conversations from within the U.S. government over centuries of U.S. policy-making on the South China Sea, starting in the 1800s.

What emerges is a clear and enduring interest among U.S. policy makers in the peaceful resolution of disputes, and the maintenance of unimpeded navigational rights, in the South China Sea. From Poling’s perspective, the freedom of the seas is under threat by China. And the U.S. is one of the only countries with the means, power and interests to rise to the challenge.

As Poling documents, the U.S. had been involved in South China Sea disputes almost from their conception in the Qing dynasty’s claims to the region. But the crystalizing moment for their policy was in 2010, when Secretary of State Hilary Clinton declared that freedom of navigation and peaceful resolution of disputes in the South China Sea was a “U.S national interest.” After that, especially in 2014-15 when China initiated a massive island-building campaign on disputed features, China’s challenge to the maritime order reached a new and dramatic high.

Poling is strongest when laying out the stakes of China’s claims. Like Kardon, he identifies the nine-dash line and the challenge it represents to UNCLOS — which he terms “one of the most ambitious and widely adopted treaties in history” — as the most pressing threat to Asia’s maritime order. But he goes a step further than Kardon, contending that “the effects of an unraveling of UNCLOS would threaten American interests from the Arctic to the Persian Gulf.” China’s claims, he argues, “undermine more than just one convention. … They strike at the most basic principle of international law: the equality of states. China’s leadership would treat international law the way it does domestic law: as a tool of power but never a constraint on it.” He concludes:

By allowing UNCLOS to be undermined without significant cost … Beijing would rightly conclude that if it can dispense with something as widely respected as the law of the Sea, then more-contested norms are fair game. And that would inform its approach to competition across the board, from economics to space and everything in between.

The common strand tying these two studies together is their shared assessment that China is using its newfound naval prowess in the region to alter the rules to better accommodate its interests. That is not the same as saying it seeks to overturn the existing maritime order wholesale. But this may also miss the point. Like all rising great powers before it, China is dissatisfied with the current order, and applies its sheer size and influence to revise it. If you’re sitting in Beijing, that may not be a bad thing. For many other countries in Asia, and worldwide, it is a cause for concern. These opposing views of the future of the Asian seas will in all likelihood continue to clash. One can only hope such clashes will not escalate to conflict. ∎

Header image: Commissioning ceremony of China’s first domestically built aircraft carrier, Shandong, at a naval base in Sanya, Hainan province, December 2019. (Li Gang/Xinhua/Alamy Live News)

Lyle J. Morris is Senior Fellow for Foreign Policy and National Security at Asia Society Policy Institute’s (ASPI) Center for China Analysis. Prior to joining ASPI, Lyle was a senior policy analyst at the RAND Corporation, leading projects on Chinese military modernization and Asia-Pacific security from 2011-2022. From 2019 to 2021, Morris served in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) as the Country Director for China.