June 4 marked 35 years since the night the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) fired its way into the center of Beijing to “liberate” Tiananmen Square from student-led protesters.

In 1989, I was a 25-year-old foreign correspondent for United Press International, based in Beijing. On April 15, former Chinese Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang — purged but still popular — died suddenly of a heart attack. The seven weeks that followed were beautiful, tragic, life-altering, and a pivotal moment in Chinese history. Two days after Hu’s death, thousands of students from Peking University and Tsinghua University marched the ten miles from the university district to Tiananmen Square to lay a memorial wreath on the Monument to Revolutionary Martyrs in the center of the square. Protesters occupied Tiananmen for the next 50 days, demanding political reform and accountability.

On the night of June 3, the PLA cleared the encampment. I witnessed them firing machine guns into crowds and running over fleeing protesters with battle tanks, in what became known around the world as the Tiananmen massacre (although the deaths mostly occurred along Chang’an or “Eternal Peace” Avenue). Several hundred protesters are estimated to have been killed, with thousands injured, and on that night I saw dozens of casualties on the streets and in makeshift morgues in hospitals.

The brave young protesters I reported on were peers my age. As survivors of the massacre, now in our 50s and 60s, our visceral memories of that night still haunt us. Yet the events of 1989 are a taboo subject in China itself, and elsewhere they have become increasingly distant — almost as far in the past to college students today as World War II was to the students of Tiananmen. June 4 is a scarlet letter day for Beijing internationally, but censored domestically. References to “June 4” are banned on the Chinese internet, so netizens use “May 35” to circumvent censorship and commemorate the event.

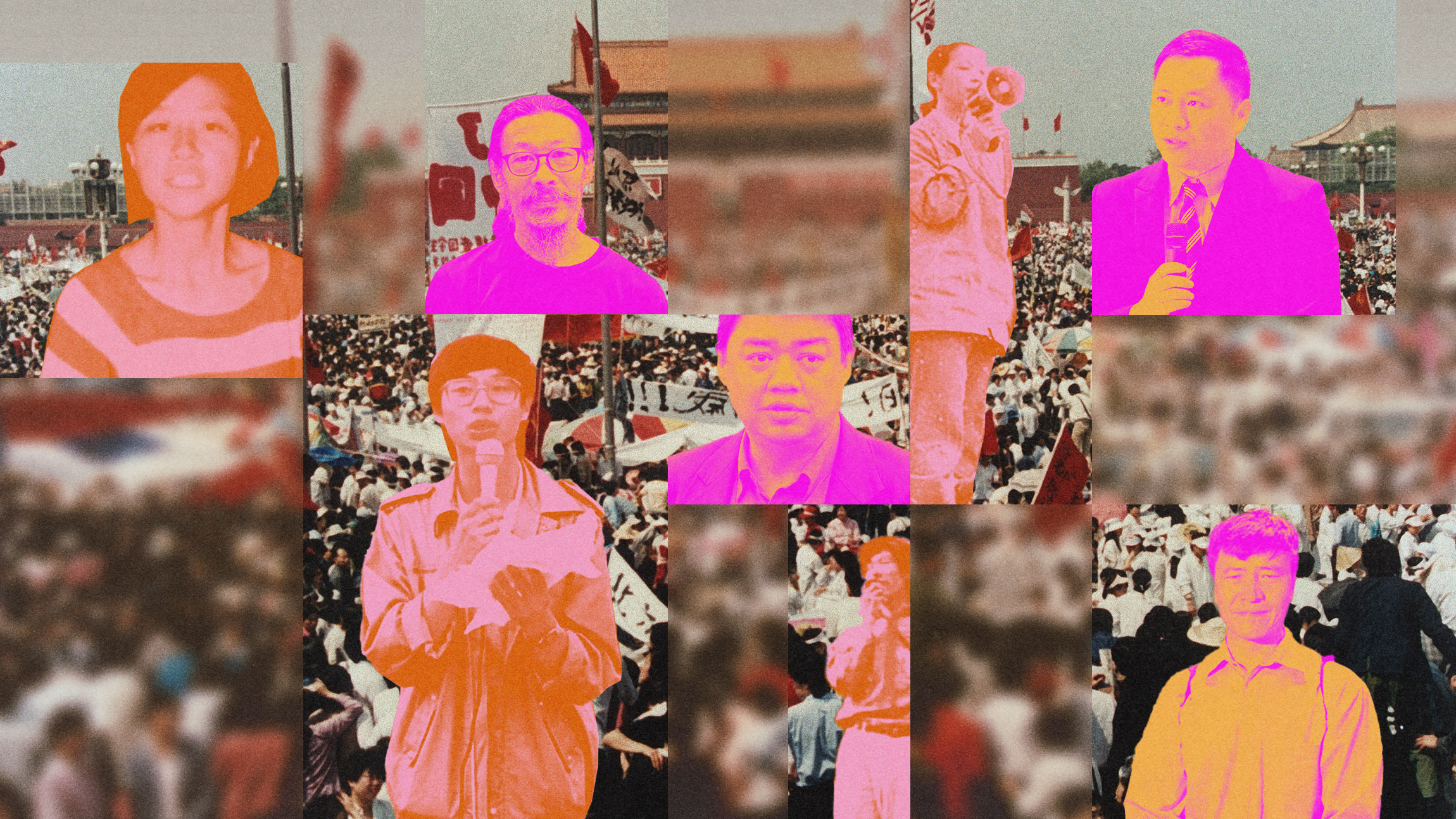

35 years later, I caught up with several leaders of the Tiananmen protests — many of whom I knew before the demonstrations, from their campus democracy activism, and whom I have kept in touch with after — and asked them to reflect on where their journey has taken them since. Each of the figures profiled in brief below has ended up in different locations outside mainland China. As they reflect on their activist youth, some of their perspectives have shifted, but their idealism continues to shine through.

Wang Dan (王丹)

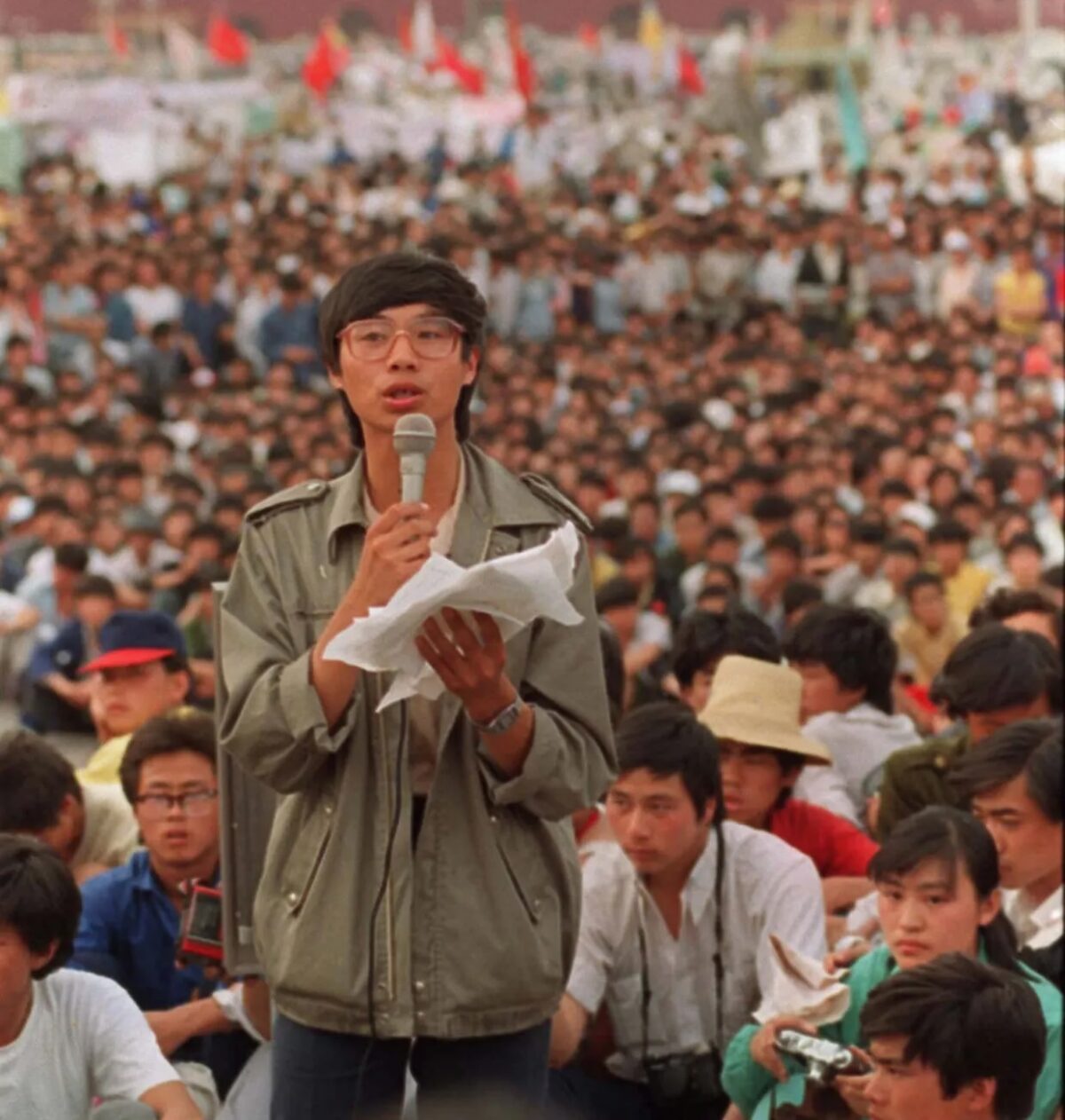

Wang Dan, one of the best-known among the 1989 student leaders, was then a 19-year-old first-year student at Peking University (known colloquially as Beida). Preternaturally mature for a freshman, his father was a popular professor at Beida and he had grown up on campus.

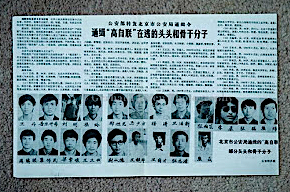

In the fall of 1988, Wang founded Democracy Salon, a weekly outdoor speaker forum which was an incubator of the Tiananmen protests, at which he was Beida’s representative to the newly-established Beijing Students’ Autonomous Union (北京高校学生自治联合会) and became a figurehead of the movement. Extremely calm and clear-thinking for a teenager, he spoke eloquently on the square about China’s historical tradition of “loyal dissent.” It was no coincidence that he emerged as both leader of the student movement and number one on the government’s most-wanted list after the crackdown.

Wang went into hiding after June 4, but was arrested on July 2, and in 1991 he was sentenced to four years imprisonment in Beijing’s notorious Qincheng Prison (reserved for politically-sensitive prisoners, including the Gang of Four in the late 1970s). He was released on parole in 1993, then re-arrested in 1995 for conspiring to overthrow the Chinese Communist Party and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

I wonder how we could have done it better … If we were more mature, we could have done things differently. But history is not made up of ifs.

Wang Dan

Instead of serving his full sentence, Wang was released on “medical parole” in 1998 — part of a deal cut between Beijing and Washington to preserve China’s Most Favored Nation trading status, then up for renewal — and sent to the U.S. He was given a clean bill of health and began his life as an exiled activist. Resuming university studies, he started school at Harvard University in 1998, completing a master’s degree in East Asian history in 2001 and a Ph.D. in 2008. He also conducted research on the development of democracy in Taiwan at Oxford University in 2009.

From 2010 to 2015, Wang taught Chinese history at National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu, Taiwan. While he was teaching a class in November 2010, a Chinese woman carrying a knife entered the room and attacked him, but he was able to grab the knife before she could stab him. Wang now lives in Los Angeles, California, where he is chairman of the Chinese Constitutional Reform Association, runs the think tank Dialogue China, and publishes widely. He has denied the veracity of a June 2023 accusation of sexual harassment by a former Taiwanese political worker, a case dismissed by the Taiwanese courts in May.

Reflecting on the 1989 protests today, Wang Dan told me:

Future student movements should be firmly based on something solid, such as the democratization of campus life or the realization of civil rights according to the Constitution; otherwise, the result is chaos. We didn’t really think about what the response to the Tiananmen protests would be. The movement was the peak of 1980s ‘reform and opening’ idealism. Now the other protest leaders and I wonder how we could have done it better, including how we made our political demands, and the way we dealt with the Communist Party, the timing of the demonstrations. If we were more mature, we could have done things differently. But history is not made up of ifs.

Wu’er Kaixi (吾尔开希·多莱特)

Örkesh Dölet — more commonly known by his Chinese name Wu’erkaixi — was the sole ethnic minority protest leader in Tiananmen Square. Of Muslim Uyghur heritage, he was born in Beijing, with ancestral roots in Ili Kazakh Prefecture in the far western border region of Xinjiang. He was a 21-year-old undergraduate majoring in education at Beijing Normal University when the protests broke out. He became the school’s representative to the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Union, and was later elected its president, helping to lead negotiations with government officials.

As the size of the protests increased, Wu’erkaixi quickly emerged as one of the most outspoken student leaders. On April 27 he organized a million-person march through the streets of Beijing, and on May 18 he achieved notoriety during the student hunger strikes (which ended when martial law was declared on May 19) when he came from a hospital bed in cotton pajamas to rebuke Premier Li Peng live on national television. Weak from hunger striking, he said:

I understand it is quite rude of me to interrupt you, Premier, but there are people sitting out there in the square, going hungry, as we sit here and exchange pleasantries. We are only here to discuss concrete matters. … Sir, you said you are here late [because of traffic congestion]. We’ve actually been calling you to talk to us since April 22. It’s not that you are late, it’s that you are here too late.

After the protests, Wu’erkaixi was number two on the most-wanted student leaders list. He fled to France with the help of Operation Yellowbird, a Hong Kong-based operation (named for the Chinese proverb “The mantis stalks the cicada, unaware of the yellow bird behind”) that helped over 400 dissidents escape arrest in China between 1989 and 1997 by facilitating their departure overseas via Hong Kong. He briefly studied at Harvard University, then in 1991 he moved to the Bay Area and continued his studies at Dominican University.

Wu’erkaixi expressed a strong desire to return to mainland China to see his parents, whom he has not seen since 1989.

In 1996, Wu’erkaixi married a native Taiwanese woman and settled in Taiwan, where he now lives. He was a political talk show host for a local radio station from 1998 to 2001, and now works as a current events commentator. He has a high profile in Taiwan due to his status as a Tiananmen dissident, and ran unsuccessfully for a seat in Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan twice, in 2014 and 2016.

Like many of the student leaders, Wu’erkaixi expressed a strong desire to return to mainland China to see his parents, whom he has not seen since 1989. But he has been unable to enter the mainland, and his parents cannot obtain passports to see him overseas, due to their sensitive political status as Uyghurs.

Wang Chaohua (王超华)

A progressive feature of the Tiananmen protests was the prominent role of women. Notable among them was Wang Chaohua. “Big Sister Wang,” as she was known among the student leaders, was a decade older than most of her fellow students. The daughter of a professor of Chinese literature at Peking University, she was a graduate student in modern Chinese literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences when the protests broke out.

Wang acknowledges that her age gave her a different perspective, in part because she had lived through the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. “Students in 1989 did not have the backing of the central government like the Red Guards did in 1969,” Wang told me. “As a result, there was a greater sense of uncertainty and a greater sense of risk. But there was also a greater sense of self-liberation.”

Wang’s participation in the protests was a matter of chance. “When the movement broke out,” she said, “I went to Tiananmen Square to see the protesters. They were calling for volunteers from each school. I was with some of my friends. I said: ‘If none of you want to join, I will join and report back.’” That decision changed her life forever.

There was a greater sense of uncertainty and a greater sense of risk. But there was also a greater sense of self-liberation.

Wang Chaohua

After the crackdown, Wang spent six months in hiding, then made her way to the U.S. in 1990, with help from Operation Yellowbird. She earned her master’s and doctoral degrees in modern Chinese literature from UCLA, where she is now an assistant professor of modern Chinese literature and culture at UCLA and an independent researcher.

Reflecting on the legacy of the protests, she said:

The seven weeks of spring 1989 were the most momentous of my life. That was the only time I experienced, and witnessed, the sensation of political emancipation, both individually and collectively, of hundreds of thousands of citizens in the People’s Republic of China. When the hugely popular movement was crushed by the army, the moment became a life-changing earthquake to everyone involved, no matter what trajectory their subsequent life took. It was also a life-changing moment for China and the Chinese Communist Party.

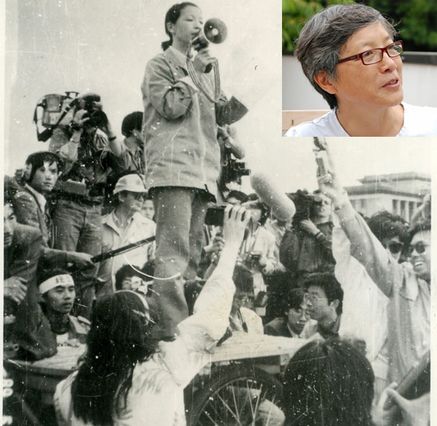

Chai Ling (柴玲)

A 23-year-old graduate student in psychology at Beijing Normal University, Chai Ling emerged as one of the most outspoken, charismatic and unyielding student leaders. Fellow protest leader Shen Tong wrote in his 1990 memoir Almost a Revolutionthat Chai “could move you to tears with her speeches.” Chai was nicknamed the “Pasionara” (passionflower) of the movement after Dolores Ibárruri, an uncompromising participant in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939.

Born in Shandong province in 1966, Chai Ling’s mother and father were both doctors in the PLA. Chai first became involved in the 1989 protests through the Peking University independent student union, which had elected her husband Feng Congde as a leader. She rose to prominence as a result of her involvement in the student hunger strike, where she was elected commander-in-chief of the Hunger Strike Committee (one of several demonstration organizations in the square).

I forgive the soldiers who stormed Tiananmen Square in 1989. I forgive the leaders who gave the orders to kill. I forgive the current leadership of China, who continue to suppress freedom.

Chai Ling

On May 23, the students of the square voted to transfer leadership from the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Union to a temporary organization called Defend Tiananmen Square Headquarters (保卫天安门广场总指挥部), which selected Chai Ling as its leader. During a May 27 meeting with other student leaders, Chai Ling and Feng Congde voted in favor of evacuating the square on May 30. At the press conference that same evening, however, Chai and Feng changed their positions and instead supported the continued occupation of the square, with Chai saying that she had been pressured into voting to leave.

After the government crackdown, Feng and Chai escaped Beijing by train. On June 13, the Public Security Ministry issued an arrest warrant which listed the names of 21 student demonstrators in order of importance. Chai Ling was fourth, after Wang Dan, Wu’erkaixi and Liu Gang. Chai and her husband spent the next 10 months in hiding, before they were smuggled into Hong Kong by Operation Yellowbird, then escaped to France.

While in hiding, Chai was nominated by two Norwegian legislators for the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize (which was awarded to Mikhail Gorbachev). She received an invitation to attend Princeton University through the China Initiative Program, an organization which provided educational scholarships for student refugees. While at Princeton, Chai studied politics and international relations at the School of Public and International Affairs.

On graduating in 1993, Chai began working at the consulting firm Bain & Company — where she began dating her current husband, Robert A. Maginn Jr., a partner at the firm (Chai and Feng divorced after leaving China). The couple married in 2001 and live in Boston, where they have three daughters. Chai Ling converted to Christianity in 2009. In 2010 she founded All Girls Allowed, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting the rights of Chinese girls and women; she has testified to Congress eight times about human rights and reproductive issues in China.

Chai Ling wrote to me with her reflections on Tiananmen:

For the past 35 years, I have tried to understand the meaning of Tiananmen. I vividly recall that last hour: standing at Tiananmen Square, watching in disbelief as the massacre unfolded around us. I finally understood that there could be only two futures for China: an outcome of continued fear, or a destiny that opens the door to true freedom and forgiveness. … It is painful for me to remember what happened on June 4, 1989, when I witnessed the death of a dream. I still mourn for what could have been. And for a long time, I battled bitterness and anger whenever I thought of [China’s] leaders who chose to take a path of destruction that day. But like my old teacher and fellow protest leader, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, I forgive them. I forgive the soldiers who stormed Tiananmen Square in 1989. I forgive the leaders who gave the orders to kill. I forgive the current leadership of China, who continue to suppress freedom. … Forgiveness does not justify wrong, but rather yields the power of judgment. I understand such forgiveness is countercultural. Yet when forgiveness arises, a lasting peace can finally reign.

Zhou Fengsuo (周锋锁)

One of the most charismatic protest leaders was Zhou Fengsuo. A physics major at Tsinghua University, he was one of the few student leaders from outside Beijing, hailing from Xi’an in Shaanxi province. At 6’2, Zhou stood out in the middle of Tiananmen square because he was a head taller than his fellow protest leaders.

Zhou had already been actively promoting democracy on the Tsinghua campus by organizing elections to the students’ union, starting a student debate club, and advocating for press freedom for the student newspaper. Then the protests broke out. Zhou was elected a member of the Standing Committee of the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Union, started the official radio station of the protests, “The Voice of the Student Movement” (学运之声), and provided medical assistance for protesters to ensure their safety during the hunger strike.

Most only remember the bloodshed and massacre, but what people really need to remember is what happened before the crackdown. It was the one time I experienced the beautiful character of the Chinese people longing for a democratic China.

Zhou Fengsuo

After the crackdown, Zhou was listed number five on the government’s most wanted list and arrested at his home in Xi’an (his own sister and her husband had turned him in to the police). Zhou was held in Qincheng Prison for a year, then freed with 96 other Tiananmen protesters (also due to China’s desire to maintain Most Favored Nation trading status with the U.S.). Instead of being allowed to return home, the government sent Zhou to Yangyuan, an isolated rural county in Hebei province, to be reeducated and “learn from the peasants.”

In 1995, after years of legal complications that prevented him from getting his passport, Zhou moved to the U.S. with no prospect of returning home legally. He received an MBA degree from the University of Chicago in 1998, worked in finance, and became a Christian in 2003. In 2007 he co-founded Humanitarian China — a group that promotes Chinese rule of law and civil society, and raises money for Chinese political prisoners — and is now Executive Director of the activist group Human Rights in China, based in New York City.

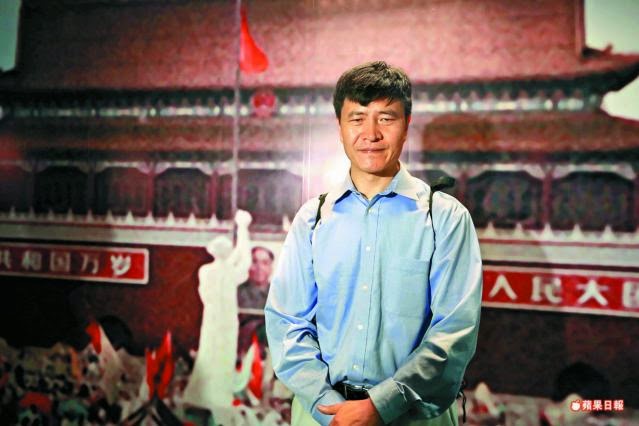

To keep the memory of the massacre alive, Zhou also co-founded (with Wang Dan and others) New York’s June Fourth Memorial Museum, which opened on June 2, 2023, in the heart of midtown Manhattan at 894 6th Avenue (8946, a reference to 4 June 1989). “I saw the auspicious address as a sign that our work is blessed,” Zhou said of the museum, which was in part a response to the 2021 closing of the original June 4 Museum in Hong Kong. The new museum showcases items from the June 4 Memorial Association (64MA), such as a shirt worn by army reporter Jiang Lin that became blood-soaked on June 4.

Zhou told me, during a visit to the museum:

For our generation, Tiananmen was the biggest event. I feel lucky to have been a part of it. Most only remember the bloodshed and massacre, but what people really need to remember is what happened before the crackdown. It was the one time I experienced the beautiful character of the Chinese people longing for a democratic China, where we could freely speak our minds. We believed we could succeed. Then I experienced the worst of human nature and saw many people die.

Han Dongfang (韩东方)

Han Dongfang was one of the few protest leaders who was not a student, but a railway worker and labor rights activist. Born in the impoverished village of Nanweiquan, Shanxi province, his family sent him to Beijing for a better high school education. But he chose not to take the college entrance exam, instead entering “the university of the streets.” He told me in a 2018 interview in his home in Hong Kong: “I educated myself. I was an avid reader of everything from Greek to Chinese classics, and worked as an assistant librarian at Beijing Normal University.”

In 1983, Han began working for the Beijing Railway Administration. His feelings about workers’ rights were emboldened, and he came to see China’s “savage” economic policies as lacking regard for society and the environment. Han believed that workers needed to protect and represent their own interests. This led him to help establish the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Union (北京工人自治联合会) once the protests began — the first independent union in China since 1949 — which grew to some 200 members before it was banned.

June 4 put a big question mark on the legitimacy of the Communist Party. The people lost trust. My dream broke that day.

Han Dongfang

On April 17, 1989, Han gave a speech on Tiananmen Square that advocated for the constitutional right for Chinese workers to freely organize. Ominously, he said that the army and the people “are like fish and water,” and should not antagonize or attack one another. While it was considered normal for many workers to hide their identities in the early stages of the protests, Han used his name freely. He told me that he felt that he needed to set an example, encouraging others to be prepared to “face the consequences” for what they said.

His emergence as the leader of the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Union earned Han the top spot on the government’s most-wanted list of worker leaders (different from the list of most-wanted student leaders). After June 4, he took off on his bicycle on what he expected to be a one- or two-year cross-country trip, to learn working conditions in China. But on June 19, on finding out that he was wanted, Han turned himself in to the police. He explained: “I wanted to avoid the humiliation of being tracked down by the police, so I turned myself in to tell them what really happened at the protests.”

Han spent 22 months in Qincheng prison. He was freed in 1992 after an international campaign to release him to the U.S. for treatment of his tuberculosis, which he contracted while in prison. He later tried to travel back to China but was expelled to Hong Kong, where he founded the NGO China Labor Bulletin and lives with his family today. As he told me:

The 1989 protests were the very first time the Chinese people themselves directly stood up to the regime. June 4 put a big question mark on the legitimacy of the Communist Party. The people lost trust. My dream broke that day. It was the turning point of my whole life.

Lu Xun, the most famous voice of China’s early Republic, wrote in his 1934 essay “Have Chinese Lost Their Self-Confidence”:

In this China of ours there have always been those who speak for the people, who fight tenaciously, who abandon their bodies in search of the truth. … In these people we discover China’s spine.

The veterans of the 1989 protests are admirable examples of “China’s spine.” All have continued their struggle for democracy and social justice, which started in Tiananmen Square 35 years ago. The protests and massacre changed the course of history, and not just in China. Without the sacrifice of those who died on June 4, it is possible that the Berlin Wall would not have fallen so suddenly later that year, or even communist governments in Eastern Europe and eventually the Soviet Union. Tiananmen, and the work of these lifelong activists, still matter.

35 years after Tiananmen, these acts of history carry important weight. Memory is the power of the powerless.

Rowena He

Many young Chinese students today know the taboo term “June 4” (六四), even if they can find few details about it. It is a censored topic, but forbidden subjects make young people curious. When an opportunity for political liberalization again arises in China, I believe a future generation will prove as idealistic as their forebears. As Rowena He (何晓清), a teenage participant in the 1989 protests in Guangzhou and author of the oral history Tiananmen Exiles who now teaches at the University of Texas in Austin, told me as a final thought: “35 years after Tiananmen, these acts of history carry important weight. Memory is the power of the powerless.” ∎

Scott Savitt is a former foreign correspondent in Beijing for The Los Angeles Times and United Press International, and author of the memoir Crashing the Party: An American Reporter in China (2016). His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere. In 1994, he founded Beijing Scene, China’s first independent English-language newspaper. He also published the magazines China Now and Contexts. Savitt was a visiting scholar at Duke University, and now lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.