Just before 8 a.m. on August 7, 2021, Murong Xuecun boarded a plane at Beijing International Airport, bound to Hong Kong. He had one suitcase with him, packed with two pairs of shoes, two pairs of pants, a few shirts, a jacket and a score of books. In Hong Kong he transferred to London, from where he had a return ticket to China in two weeks.

He did not use it. Instead, after five months stuck in London due to Covid regulations, he continued with his exit plan and moved to Melbourne, Australia, where the writer now lives in exile from the land of his birth.

Before that summer morning, Murong — previously styled as a single word, the pen-name of Hao Qun — was arguably the last dissident writer left in China. A best-selling novelist, in 2011 he started to publish articles, in Chinese and later in English, that criticized China’s government policies and state censorship. In 2013, his writing was banned. Other dissenting voices like him had already left the country — Ma Jian in 1999, Liao Yiwu in 2011 — but he chose to remain in his homeland, to bear witness to what was happening to it.

“By 2021,” Murong told the China Books Review, “I felt sure that if I stayed I would be arrested.” He was urged to leave by friends, and by his Australian publishing house, Hardie Grant Books, who were about to publish Deadly Quiet City: Stories From Wuhan, Covid Ground Zero, a nonfiction work that documents ordinary lives in Wuhan during the first lockdown of the Covid pandemic. “The risk of being imprisoned was the biggest factor,” he said, “but another reason was that I couldn’t publish in China.” It was time to go.

One year after leaving, on the Bumingbai podcast, Murong told the host Yuan Li: “I can’t call myself an exile writer. I might just be a Chinese writer temporarily living abroad.” Another has year passed, and he has changed his tune. At an interview in the WeWork building in the financial district of New York this summer, Murong said that he does now identify as a writer-in-exile. Most media outlets refer to him as such, he explained, and his friend Wu’er Kaixi — a Tiananmen student leader based in Taiwan — told him that the sooner he embraces this identity, the better he can confront its reality.

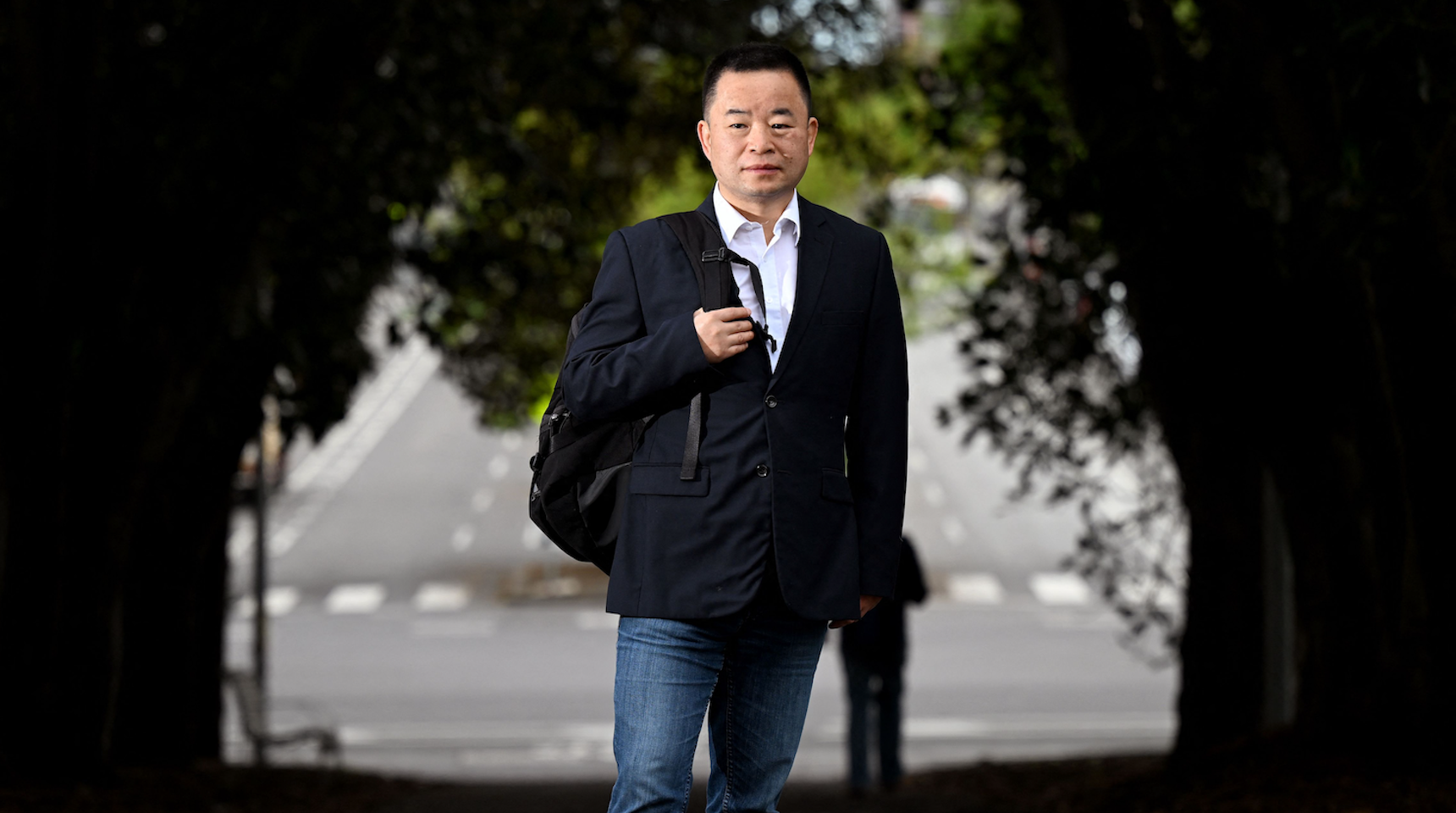

Unlike his often nihilistic and dark literary works, Murong is warm in person. He is a short and stout man, with dimples on his face that dance when he smiles, a shy manner and a bubbly sense of humor. Yet he talks with assurance, hands still, as if you are the only person in the room.

“I cannot live my life out of a suitcase, ready to return to China,” he said. “I need to contemplate how I can navigate the remainder of my life, and fulfill my duty as a writer, if I can never go back.”

Murong was born in 1974, in a mountainous hamlet near Baishan, Jilin province. His parents were farmers, and when he was two, they moved to rural Shandong. “We were very poor during my childhood,” he said. “The greatest annoyance in Shandong was the lack of books.” Over the autumn wheat harvest and again at Chinese New Year, the village they lived in invited public storytellers to perform. At night, perched on a tiny wooden stool in the front row, he listened to fantastical stories about fox spirits and historical battles. As he looked at the rustling trees nearby, he imagined them transforming into mythical creatures of lore.

With a longstanding love for novels and poetry, as an undergraduate Murong was head of the literature club at China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing, even though he was studying to be a lawyer. In 2000 he moved to the southern city of Shenzhen, and later to Chengdu in Sichuan province, working first as a legal consultant at a state-owned enterprise, then as a human resources manager at the cosmetic manufacturer Softto.

“After I started working,” he said, “I became a more worldly person and put away my interest in literature.” Instead, in his free time he played a computer game that involved slaying thousands of virtual beetles. One afternoon in April 2002, he had reached level 31 and a sudden realization struck him: what was he doing with his life? He let the beetles devour him, turned off the computer, and contemplated how else he could use his time.

Intrigued by the confessional posts about city life he read on BBS discussion forums online, Murong decided to write a novel. The result was Leave Me Alone: A Novel of Chengdu (2003), which he self-published online, serially. The story follows three men pursuing their desires while stuck in dead-end jobs, spending their time gambling, doing drugs and visiting prostitutes. By the time he posted chapter seven, the novel was a hit. A published version followed swiftly, although 10,000 characters were cut to tone back his exposé of the dark corners of contemporary China.

Two other novels followed on the back of its success, which were also subject to censorship. In Heaven to the Left, Shenzhen to the Right (2004), following young entrepreneurs struggling to make it in Shenzhen, he had to change a depiction of the 1989 Tiananmen protests into a campus fight. In Dancing Through Red Dust (2008), about a corrupt lawyer who ends up on death row, 20,000 characters were cut. Regardless, by now Murong was a literary celebrity. His first novel sold three million copies according to his publisher, was adapted into a television drama, and he garnered 8.5 million followers on Weibo. His novels didn’t directly touch on politics, but confronted the shadows and decay within society. He felt he was making a difference.

Murong’s first nonfiction book was China: In the Absence of a Remedy (originally titled The Missing Ingredient), a firsthand account of 33 days he spent undercover in a pyramid scheme network in Jiangxi province. He won the People’s Literature Award in 2011 for it, but at the award ceremony an organizer asked to look at his acceptance speech, which was a screed against how the editor of the book had censored even minor details. Barred from delivering the speech, he walked out of the event, making a symbolic gesture of zipping his mouth shut as he left.

That was the start of Murong’s transformation from novelist to dissident.

I need to contemplate how I can fulfill my duty as a writer, if I can never go back.

Murong Xuecun

China was not always this way. In 2008, public intellectuals were engaging with each other openly, challenging the status quo on blogs and the Twitter-equivalent of Weibo. “The blooming landscape of social media and the ripple effect of hosting the Olympics,” Murong said, “had opened a space for public discussion.” But after Xi Jinping was appointed General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in late 2012, intellectuals were silenced one after another. Before he realized it, Murong was one of the last voices speaking out. “I had no boss or wife,” he put it, “so I felt I should be braver and speak for those who cannot or dare not. It’s the right thing to do.”

Through the 2010s Murong lived in Beijing, writing full time. “I felt like I was living in a house transparent to the state,” he said. Often, he would be summoned to “drink tea” with the police, a euphemism for an informal interrogation, where he was asked about recent activities. These state security agents — they said they were from the guonei anquan baoweiju, a subdivision of the Ministry of Public Security, though he simply calls them ‘secret police’ — often suggested he move to other regions of Beijing, as they didn’t want him on their turf. He was placed under house arrest twice: in 2013 when he met with a Japanese journalist, and in 2016 when he attempted to meet with the former President of Germany, Joachim Gauck.

In May 2013, Murong’s blog and Weibo accounts were deleted. “I wrote over 200,000 words of reading notes and comments on politics,” he said, “and now it’s all gone.” No longer able to publish in China, he wrote a column about Chinese politics for The New York Times from 2013 to 2016. He also worked as a ghostwriter for various projects, but these jobs were often thwarted by state security agents who would contact his employers and pressure them to terminate the contacts. “From 2011 to 2016,” he said, “they cut off almost all my income and I couldn’t do anything.”

In the spring of 2016, with six colleagues he set up a public account on WeChat called Seven Writers, which posted critical journalistic essays every day. Murong’s contributions were mostly satirical, parodying Party pronouncements through the mode of classic Chinese literature. Half a year later, he woke up to discover the account had been taken down, its posts scrubbed from all existence with no acknowledgment or notice as to why.

Yet in the years leading up to his departure in 2021, Murong never considered leaving China. Despite facing a publishing ban, he led a comfortable life as a respected writer within intellectual circles. “I did not want to be a deserter fleeing the country,” he explained. He wanted to preserve his credibility to speak to the world about China by being present on the ground.

In 2020, Murong bore witness to the early Covid epidemic in China. On April 6, he made his way to Wuhan, just before it lifted its first lockdown two days later. He interviewed nurses, doctors, delivery workers, government officials, janitors, citizen journalists. He asked over 30 people where they believed the virus came from; almost everyone said that it originated with American soldiers who were there two months ago for the Military World Games. “I prefer to view them as victims of propaganda,” he remarked, “rather than labeling them as villains or inherently foolish.”

Deadly Quiet City tells the stories of eight Wuhan residents, but the narrative that affected him most was that of a retired hospital custodian, referred to as Jin Feng in the book. When diagnosed with the virus, she contemplated taking her own life to prevent infecting her husband and her mentally disabled son. Her husband convinced her to seek medical assistance, and Jin recovered after a week. But her son was infected and tragically succumbed a few days later, due to the lack of available hospital care.

On May 3, a call came from a state security agent asking what he was doing in Wuhan. He said he was just looking around. “Okay, just be careful,” the voice on the other end of the line intoned. “You don’t want to catch the virus.”

Murong knew this was the police’s way of telling him that they were watching. He decided to leave Wuhan but didn’t want to return to Beijing either, back to the transparent house. So on May 7, after a month in the city, he took a train to Mount Emei in Sichuan province, and holed up in a hotel at the foot of the mountain to write his book.

Ten days after Murong left Wuhan, his friend Zhang Zhan, a citizen journalist who had travelled to Wuhan in February to report on the Covid outbreak, was arrested. A photo of Zhang Zhan, him and a few other citizen journalists in Wuhan had been posted on social media, and the police had seen it. Everyone except him had been summoned for questioning. A friend warned he would be next.

In a nervous reaction that brought him back to his college days, Murong downloaded the game Zombie vs. Plants and played it for two days straight. He didn’t get very far: every half hour or so, he stepped outside his room to look for suspicious people in the hallway. But the knock on the door never came. He did get a call asking about his recent activities, and fabricated a story he was working on: a science fiction novel where a person’s life could be viewed by scanning a QR code on their tomb. “That sounds like a good book,” the police responded, “keep working on it.”

For eight months at Mount Emei, Murong wrote in fear. After finishing each chapter, he sent it to his editor in Australia, Clive Hamilton, then wiped the material from his laptop. He kept his computer in sight all the time, even in the bathroom. “I felt like I wasn’t a writer,” he said, “but a criminal at large.”

By summer of 2021, as the book was in the final editing stages, Murong’s publisher was urging him to leave China as soon as possible, convinced that he would be arrested when it was released. This was a reasonable fear: by now 38 of Murong’s contacts, including lawyers, journalists and scholars, had been arrested for speaking out against government policy. Some were released after brief spells; others are still serving time.

At the airport, Murong wasn’t sure if he would be allowed to leave. In his mind, he gave it a 50 percent chance. But the border official just asked routine questions about his trip to England, looked at his return ticket and single suitcase, and let him go. He was 47 years old, and tried to treat it as a routine trip. “The airport is a place full of stories,” he mused. “I felt psychologically repelled by the fact that this could be my farewell to China, so I tried not to think about it.”

I often ask myself, why wasn’t I arrested? Why was I the one who got away?

The Chinese word for “exile” is 流亡. The first character, liu, means drifting. The second character, wang, means fleeing but also death. It is a painful word that gestures to the fate of an exile dying in a foreign land.

Like many writers in exile, on leaving China Murong experienced survivor’s guilt and an identity crisis. During his participation in the White Paper protests in Melbourne, holding a sheet of white paper, he made the decision not to share the images on Twitter. “I would have posted it if I was in China and taking risks to [participate],” he put it. “But in Melbourne, a distant and strange land, and a free country, I felt too embarrassed to post it.”

“I often ask myself, why wasn’t I arrested?” he said. “Why was I the one who got away?” He thought of Su Dongpo, a Song dynasty poet who was exiled to Lingnan in China’s south, then wrote a poem praising the deliciousness of local lychee to show the central government that he was not broken. “It’s no simple feat for a writer to leave their homeland and carry on with their craft,” he reflected. “The connection to one’s roots is lost. It’s a question that I, too, must contemplate.”

Yet there are consolations of exile. Murong hasn’t dreamt about being arrested in a long time. In Beijing, he would rarely make plans for the next year; he couldn’t be sure if he wouldn’t be in prison. In Australia, his writing could be published without censorship. “I didn’t want to leave China because I thought I could still do something,” he said. “But once I left, I realized there are many more things to do in the free world. It’s like I’ve been liberated from a cage. Now I can write anything I want.”

Since he left, Murong has almost completed a screenplay about Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Prize laureate who passed away in prison in 2017 after years of persecution. He is working on a novel about the relationship between a dissident poet and their secret police handler. And he is learning English to the level where he can give a book talk. He misses his friends in Beijing, their lively gatherings, and longs for the locations in China he has not visited, such as its ancient capital Luoyang. “Probably,” he admits, “I will never get the chance to visit those places.”

“He’s still very engaged with China,” said Clive Hamilton, his editor, in a Zoom interview. “It’s like part of him hasn’t left. Murong is a brilliant writer … I’d like to see him broaden his canvas on which he paints his stories… [as] his consciousness shifts from China to the broader world.”

There is another translation of “exile”: 流放. The first character means drifting. The second character means to let go. In exile, one can also find liberation.

“When I was in China, I thought it was my whole world,” Murong said. “But now I’m in the outside world, and this has become my reality. I was like a person standing inside a cookie tin, watching as the lid slowly closed. But now, with a loud bang, I have jumped out.” ∎

Header: Murong Xuecun in Melbourne, October 2022, one year after fleeing China.

Alec Ash is a writer focused on China, and editor of China Books Review. He is the author of Wish Lanterns (2016), following the lives of young Chinese in Beijing, and The Mountains Are High (2024) about city escapees in Dali, Yunnan. His articles have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic and elsewhere. Born and educated in Oxford, England, he lived in China from 2008-2022, and is now based in New York.

Originally from mainland China, Diane Chu is a student and journalist at Yale University who closely follows political and cultural topics in her homeland.