If just one lesson could be drawn from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it must be that deterrence would have been a lot cheaper than war. Yet democracies seem to be getting worse at deterrence. The record of the past few years is marred with failures and signs of trouble.

In August 2021, the Taliban toppled the democratic government of Afghanistan just six weeks after watching the United States vacate its last major military base in the country. Sixth months later, Vladimir Putin, unfazed by Washington’s threats of sanctions, assaulted the capital of Ukraine and plunged Europe into its most destructive conflict since World War II. As that conflict raged, Iran equipped Hamas to initiate a war with Israel and, once the war had started, mobilized several other terrorist proxy groups to rocket Israel, attack commercial shipping in the Red Sea, target U.S. warships, and strike U.S. military positions in Iraq, Syria and Jordan.

North Korea has also been undaunted by either United Nations Security Council resolutions or American sanctions; last year it resumed testing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) for the first time in more than five years and became a supplier of arms and munitions for Russia’s war in Ukraine. Meanwhile, in South America, Venezuela’s dictator Nicolás Maduro appears to have concluded that Washington’s bark is worse than its bite: He has threatened to annex much of Venezuela’s oil-rich neighbor, Guyana. In a bold reprisal of Soviet mischief in the Americas during the Cold War, Beijing is expressing sympathy for Venezuela’s position while also developing Chinese intelligence facilities and a plan for a military base on Cuba.

But looming on the horizon is the specter of a conflict more consequential than all these flashpoints combined: Chinese supreme leader Xi Jinping has vowed to “reunify” Taiwan with mainland China through force of arms if necessary. Xi’s public statements about a coming “great struggle” against China’s enemies provide a window into his intentions — one the world would be unwise to ignore.

Deterrence [is] a lot cheaper than war. Yet democracies seem to be getting worse at deterrence.

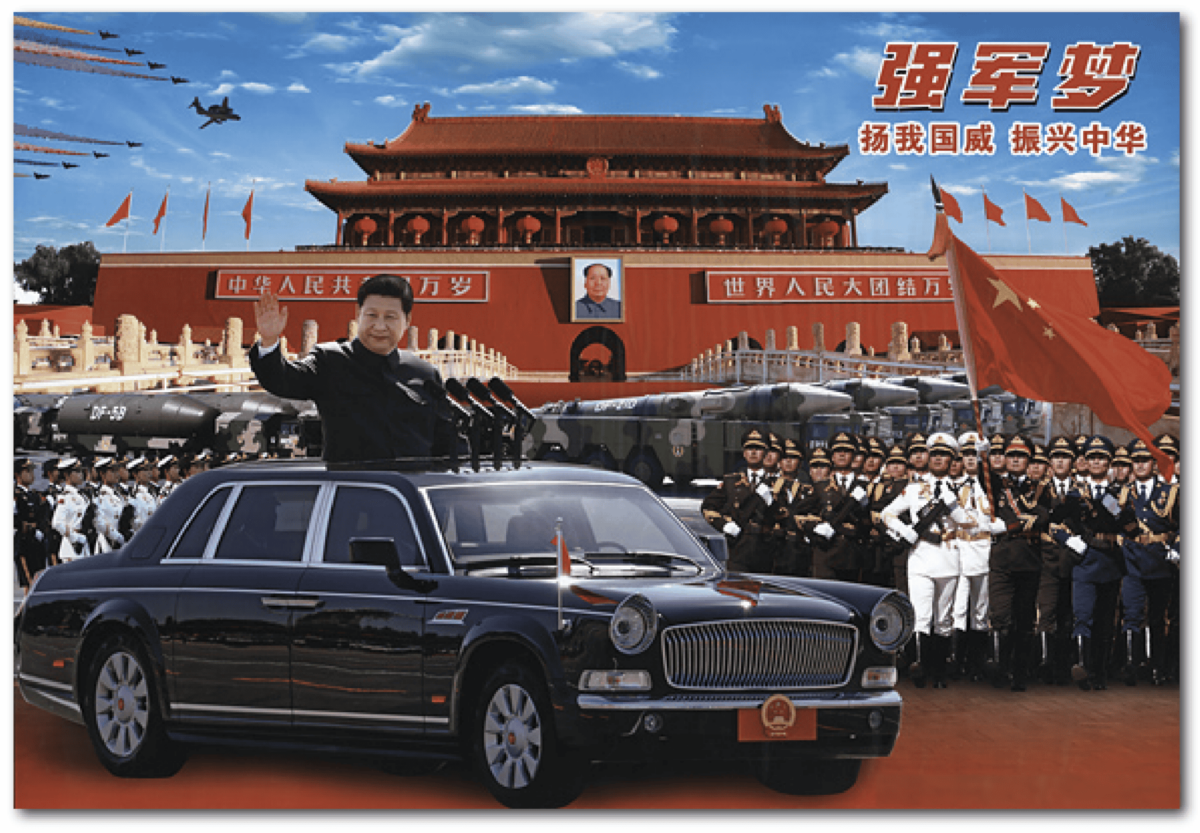

More than once, Xi has described unification with Taiwan as a prerequisite for achieving his broader objectives for China on the world stage, a vision he calls “the Chinese dream for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” In a 2017 address to the 19th Party Congress in Beijing, Xi said that “complete national unification is an inevitable requirement for realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

In 2019 in Beijing, at the Meeting Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Issuance of the Message to Compatriots in Taiwan, he said: “The rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and reunification of our country are a surging popular trend. It is where the greater national interest lies, and it is what the people desire.” In October 2021, he delivered an address about Taiwan at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in which he uttered the word “rejuvenation” more than two dozen times.

The implication is hard to miss: Xi is equating a failure to subsume Taiwan with a failure to enact his overarching goals as China’s leader.

Although Xi has been less concrete — at least in public — about a timeline, he has exhibited an impatience that distinguishes him from his predecessors. “The issue of political disagreements that exist between the two sides must reach a final resolution, step by step, and these issues cannot be passed on from generation to generation,” Xi told an envoy from Taiwan in October 2013. This and similar statements by Xi are a far cry from then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s famous line, in 1984, that China could wait “1,000 years” to unify with Taiwan if necessary.

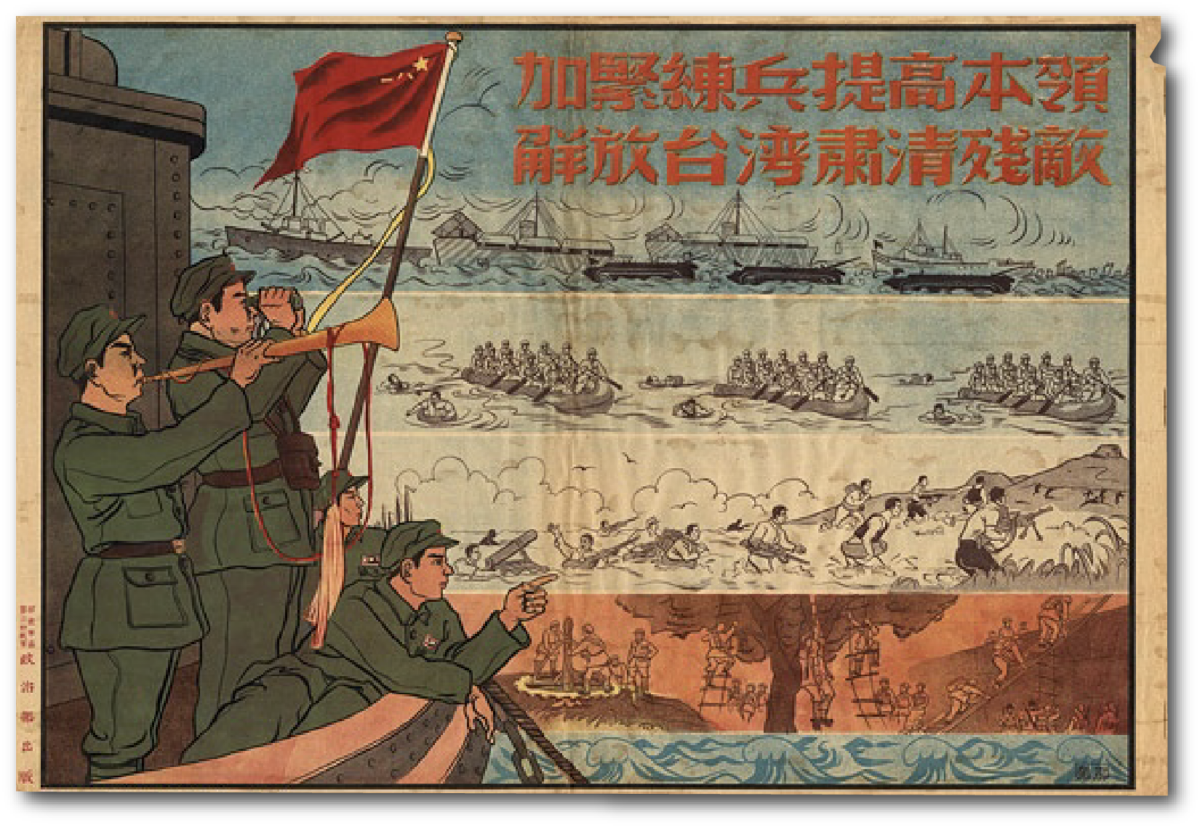

And whereas Xi’s more immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, framed war as something Beijing would wage in response to a declaration of independence by Taiwan, official propaganda under Xi has gone further by suggesting that force may be used to compel unification, not just to respond to a Taiwanese bid for formal independence.

Xi seemed to confirm this in his face-to-face meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden in San Francisco in November 2023. According to a senior U.S. official who briefed reporters after the summit, Xi said his “preference was for peaceful reunification but then moved immediately to conditions that the potential use of force could be utilized.” When Biden responded by “assuring Xi that Washington was determined to maintain peace in the region,” Xi’s response was blunt. Per the U.S. official, President Xi responded: “Look, peace is . . . all well and good, but at some point we need to move toward resolution more generally.”

In other words, Xi appeared to elevate the goal of unification above the goal of peace. His tough signaling extended to China’s official read-out of the meeting, which quoted Xi as follows: “The United States should embody its stance of not supporting ‘Taiwan independence’ in concrete actions, stop arming Taiwan, and support China’s peaceful reunification. China will eventually be reunified and will inevitably be reunified.”

That may have been the first time Xi publicly called for U.S. “support” for unifying China and Taiwan. Such language marks a fundamental revision of Beijing’s long-standing demand that Washington refrain from supporting Taiwan independence. Simply put, and contrary to the assumptions of many Western analysts, Xi’s moves aren’t aimed at maintaining the decades-old status quo in the Taiwan Strait but at ending it.

Xi knows this may require war. In key speeches over the past few years, he has admonished his party and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Army, to prepare for a major conflict.

“In the face of major risks and strong opponents, to always want to live in peace and never want struggle is unrealistic,” Xi said in his November 2021 speech to the Sixth Plenum of the 19th Party Congress in Beijing. “All kinds of hostile forces will absolutely never let us smoothly achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. Based on this, I have repeatedly stressed to the entire Party that we must carry out a great struggle.”

In this seminal address, kept secret for two months before being published in a Chinese-language journal (where it was missed by Western journalists and many scholars), Xi praised then paramount leader Mao Zedong’s decision to enter the Korean War in 1950.

“Facing the threat and provocation of the United States,” Mao and his comrades made the brave decision to go to war, Xi said. As he put it:

The Party Central Committee and Comrade Mao Zedong, with the strategic foresight of ‘by starting with one punch, one hundred punches will be avoided,’ and the determination and bravery of ‘do not hesitate to ruin the country internally in order to build it anew,’ made the historical policy decision to ‘resist America and aid Korea’ and protect the nation.

The language shows Xi framing Mao’s move as a preemptive attack to avoid what Xi called “the dangerous situation of ‘invaders camping at the gates.’” Xi’s choice of words was surely meant to signal his own preparedness to wage war under analogous circumstances and, chillingly, his tolerance for risking national “ruin” as the price of victory over China’s enemies. “No matter how strong the enemy is, how difficult the road, or how severe the challenge, the Party is always completely without fear, never retreats, does not fear sacrifice, and is undeterrable,” he said.

While the speech’s description of the United States as an enemy was made in a historical context, Xi has more recently cast Washington as China’s explicit, present-day adversary. “Western countries headed by the United States have implemented containment from all directions, encirclement and suppression against us, which has brought unprecedented severe challenges to our country’s development,” Xi said in a March 2023 address. That address was one of four made by Xi that month in which he underscored the need to prepare for war.

In the first of the addresses, to delegates of the National People’s Congress on March 5, Xi said China must end its reliance on imports of grain and manufactured goods. “In case we’re short of either, the international market will not protect us,” Xi declared. In a speech the following day, he urged his listeners to “dare to fight, and be good at fighting.” On March 8, he unveiled to an audience of generals a National Defense Education campaign to unite society behind the military, invoking as inspiration the Double Support Movement, a 1943 campaign for society-wide militarization. In the fourth speech, on March 13, Xi announced that the “unification of the motherland” was the “essence” of his great rejuvenation campaign — a formulation that exceeded even his previous statements calling unification a “requirement” for China’s rejuvenation.

Xi has described unification with Taiwan as a prerequisite for achieving his broader objectives for China on the world stage.

In light of all this, the world should regard gravely Xi’s exhortation, contained in his “work report” to the 20th Party Congress in October 2022, that the Chinese Communist Party must prepare to undergo “the stormy seas of a major test.”

These statements, it is important to understand, weren’t propaganda meant for Western ears. They were authoritative instructions delivered by Xi to the Chinese Communist Party. They are taken seriously by the country’s governing apparatus. We should give them at least the same weight that analysts ascribe to leaked Oval Office conversations about war and peace.

I have singled out Xi Jinping personally as the object of deterrence and for good reason: After more than a decade of consolidation and centralization of power, no other decision maker counts nearly so much as Xi when it comes to questions of war and peace. His personal assumptions about China’s chances in a conflict, and about the intentions and capabilities of Taiwan and the United States and its allies, are key variables informing his calculus on whether to wage war. As the Australian strategist Ross Babbage reminds us, “deterrence involves using one’s actions to deliver the strongest possible psychological impact on the opposing decision-making elite so as to persuade them to desist, delay, or otherwise alter their operations to one’s advantage.”

In today’s China, the “decision-making elite” more or less boils down to one man.

It is tempting to imagine that the ripple effects from Beijing subjugating Taiwan could be contained, especially if the island were coercively annexed without a wider and highly destructive war. After all, there were dire predictions in the 1960s and 1970s about what a U.S. loss in Vietnam would spell for the future of Asia and for American power in the region — predictions that never came to pass. “Domino theory” didn’t play out and communism didn’t spread from Indochina. In the decades after Saigon fell in the spring of 1975, U.S. economic and political influence actually grew in Asia, even as Washington’s military footprint decreased in the region.

But this is the wrong analogy. A more apt precedent would be Imperial Japan’s aggression and brief domination of the Asia-Pacific in the first half of the 1940s as Tokyo foisted its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere upon hundreds of millions of unwilling subjects. Xi Jinping, in a landmark speech in Shanghai in 2014, even declared, “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia, and uphold the security of Asia” — a formulation eerily similar to the “Asia for Asians” slogan Tokyo adopted in 1940 when it set out to impose its concept of a self-contained, regional economic and security bloc controlled by Japan.

The subjugation of the island nation by Beijing would have profound ramifications for geopolitics, trade, nuclear proliferation, and technology. Taipei’s fall would represent much more than a mere Vietnam-style unification; it would herald the dawn of a new empire — one that would suit Beijing’s brand of muscular authoritarianism and strongly disfavor the interests of the United States and its fellow democracies. The coercive annexation of Taiwan, even in the absence of an American intervention, would not alleviate Sino-American tensions but would supercharge them.

This is why Taiwan’s partners need to be clear-eyed about what would be required of them to break a Chinese blockade or repel an invasion. What the American people would sacrifice to win a Taiwan war would be far greater than the indirect support they have, to date, provided to Ukraine. There is simply no realistic hope that Taiwan can hold out for long against China without America committing directly to the fight. If America’s support for Ukraine today is analogous to its indirect support for the United Kingdom and other allies through its Lend-Lease program in 1941, U.S. support for Taiwan amid a Chinese attack would be more akin to its direct participation in the 1950–53 Korean War.

This makes preventing war all the more desirable and important. I believe that Xi Jinping, contrary to his declaration that the Chinese Communist Party is “undeterrable,” can be persuaded that a decision to wage war over Taiwan would be a grave miscalculation. He has demonstrated an appetite for risk, but his record isn’t that of a reckless gambler.

But in order to deter Xi, the United States and its allies need to pursue several urgent but practical military steps over the next 24 months. This isn’t because economic, financial, informational, and diplomatic tools are unimportant when trying to dissuade adversaries; it’s because they have little chance of succeeding in the absence of credible hard power — the sine qua non for effective deterrence.

Taipei’s fall would represent much more than a mere Vietnam-style unification; it would herald the dawn of a new empire.

China may be physically close to Taiwan, but geography offers asymmetric advantages for Taiwan too. Taiwan’s mountainous coastline, poor landing beaches, and urban sprawl present foreboding challenges for an invader. A favored metaphor in Taiwan is that it should adopt the strategy of a porcupine, making itself unappetizing or, if that fails, fatal to a hungry predator.

But the real blessing for Taiwan is the strait that separates it from China. The Han dynasty statesman Kuai Tong advised that even a powerful army should refrain from attacking well-defended border cities protected by “metal ramparts and boiling moats.” Taiwan, the United States, and key U.S. allies should embrace a “boiling moat strategy.” The Chinese military’s center of gravity in a Taiwan war would be its navy. The Taiwan Strait would be its graveyard.

To do this, however, democracies must increase their defense spending sharply to keep key legacy systems working and to scale up the production of munitions. This is because, if we do succeed at deterring Xi for the remainder of the 2020s, it will be thanks largely to “legacy” military systems — not futuristic programs that have yet to bear fruit. The U.S. must marshal technologies and weapons systems that, for the most part, already exist in the arsenals of the United States and its partners or have been developed and tested and are eligible for production and procurement.

As General Christopher G. Cavoli, America’s senior military officer in Europe, told me, one of the lessons of the Ukraine war is that “kinetic effects are what determine results . . .and the majority of kinetic effects are from legacy systems. So don’t ‘sunset’ legacy systems prematurely while awaiting the ‘sunrise’ of next-generation capabilities. Otherwise, we’ll be left stranded at midnight.”

Taiwan and its partners must also have enough munitions not only to deny Beijing a speedy victory but also to continue fighting in case Xi chooses to wage a protracted war. At present, democracies may lack sufficient munitions for either scenario. The preexistence of industrial capacity for making these weapons will be a crucial element of effective deterrence.

One silver lining is that in war, time tends to be a better friend to the defender than to the aggressor. “An offensive war requires above all a quick, irresistible decision,” the Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote in his classic On War. “Any kind of interruption, pause, or suspension of activity is inconsistent with the nature of offensive war.”

If Beijing stumbles in its initial onslaught, Taiwan will have a much better chance at winning a conflict. It would be a shame for Taiwan to make it that far only to fail in a follow-on, protracted phase of war because democracies didn’t have the foresight to invest enough in military manufacturing.

Admiral Yoji Koda, a former commander of the Japanese fleet, told me that Americans often consider the June 1942 Battle of Midway to be the decisive naval engagement of World War II. Japanese military historians don’t all see it that way, he said. Rather, it was the months of sea battles that followed, many of them without names, during which the U.S. armed forces decisively wore down the Imperial Japanese Navy thanks to superior production of ships, munitions, aircraft, and incremental technologies, such as those that gave the Americans an edge in nighttime combat. This “War of the Destroyers,” as Koda calls it, was more costly to Japan than the Battle of Midway. The United States and Japan — now great allies — should be aiming together for a capacity to win wars, not just battles.

Taiwan’s mountainous coastline, poor landing beaches, and urban sprawl present foreboding challenges for an invader.

China’s vulnerabilities, after all, are many. Beijing may control the world’s largest navy, but its surface vessels (without which it cannot secure military control of Taiwan) would be ripe targets in a war — not only for American attack submarines, but for U.S. heavy bombers that can reach the Western Pacific in hours and launch fusillades of antiship missiles from a relatively safe distance. (This is why the U.S. Air Force should also prepare for a more central role in a Taiwan contingency than its current priorities suggest.)

China may have a large arsenal of antiship ballistic missiles to keep U.S. aircraft carriers at bay, but Washington has formidable allies in the region that could help thwart Beijing’s war aims if they joined an effort to defend Taiwan. This is why Tokyo should publicly embrace the near inevitability that it would be compelled to fight in the event China attacks Taiwan. A clear statement of intentions by Japan now, in peacetime, would reduce the odds of a war by helping to dispel wishful thinking in Beijing that Tokyo would remain passive.

If we can deter a Taiwan war through the end of this decade, then newer weapons systems may enter democratic arsenals that can, if we play our cards wisely, deepen the allied “offset” of China’s growing military juggernaut. But long-term deterrence won’t be achieved haphazardly as a by-product of other defense objectives; it will be achieved when it is the primary goal.

A long and sorry tradition of underestimating Beijing’s capabilities and intentions is giving way to sober new analyses in Taipei, Tokyo, Canberra, and Honolulu (home to the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command). In Washington, the bromide that “war isn’t in Beijing’s interest” is finally, if slowly, beginning to subside. But the often parochial and ill-coordinated defense budgets requested by allied military services and voted on by our legislatures leave the impression that deterrence is at best a secondary objective, something leaders evidently hope to achieve by accident or on the cheap. This thinking must change, and fast.

The U.S. military has a smaller active-duty force today than at any time since the early stages of World War II. The U.S. defense budget, adjusted for inflation, is shrinking at a time when wars are proliferating. As a percentage of GDP, U.S. annual defense spending today (at 3.1 percent) is less than half what it was at the peak of the Reagan administration (6.8 percent), which presided over the most decisive decade of the Cold War without the need for a direct conflict with the Soviet Union. These statistics suggest Washington is forgetting the hardest lessons of the twentieth century — the ones that were written in blood.

On October 19, 2023 — at a moment when Israel was fighting on multiple fronts, U.S. forces and Iranian proxies were exchanging fire in Syria and Iraq, Ukraine was approaching the two-year mark of its war for national survival, and North Korea was funneling arms and munitions into Putin’s war machine — President Biden summarized the stakes in a sobering Oval Office address.

“We’re facing an inflection point in history — one of those moments where the decisions we make today are going to determine the future for decades to come,” he said in his opening line.

Biden made no mention of China in the speech. Yet Beijing serves as a propaganda engine for, and the primary economic and diplomatic sponsor of, the revanchist autocracies that Biden did single out in his address: Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

While Beijing often hides the extent of its support for Moscow, Tehran, and Pyongyang, the fig leaf is slipping away. The aims and actions of these four regimes are increasingly interrelated, as exemplified by Xi’s “no-limits” pact with Putin on the eve of Russia’s 2022 reinvasion of Ukraine, and by Moscow and Beijing hosting leaders from the terrorist group Hamas in the wake of its massacre of more than 1,200 Israelis on October 7, 2023. U.S. Secretary of State Tony Blinken in April visited Beijing and declared China was “overwhelmingly the number one supplier” of Russia’s war machine, and expressed doubts that Putin could have sustained the war this long without the material support from Xi Jinping.

Whether Xi is acting opportunistically or according to a grand design (or, more likely, both), it is clear he sees advantage in the compounding crises on multiple continents — crises that run the risk of exhausting the United States and its allies and setting the table for a possible move on Taiwan.

Indeed, Xi has made statements over the past few years that suggest he would agree with Biden that the world has reached a historic inflection point. The difference is that, from Xi’s perspective, this is good news.

“Since the most recent period, the most important characteristic of the world is, in a word, ‘chaos,’ and this trend appears likely to continue,” Xi told a seminar of high-level officials in January 2021. Xi made clear that this was a useful development. “The times and trends are on our side,” Xi continued. “Overall the opportunities outweigh the challenges.”

Official texts make clear that this is a moment Xi has been long preparing for. A 2018 military textbook on Xi Jinping Thought, stamped “internal use only,” states the following:

The world is now undergoing a transition so massive that nothing like it has ever been seen before. At its core, this transition is being driven by the following changes: The United States is becoming weak. China is becoming strong. Russia is becoming aggressive. And Europe is becoming chaotic. . . . The Chinese nation-state is rising and the Chinese ethnos is resurgent. This is an historic turning point.

Xi has since cast himself not just as a beneficiary of the current situation but as an architect. In March 2023, more than a year into Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine, Xi visited Moscow to strengthen his cooperation with Vladimir Putin. As he bade farewell to Putin at the Kremlin, Xi was captured on video telling his host: “Right now there are changes, the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years, and we are the ones driving these changes together.”

Any realistic and effective strategy for deterring Beijing cannot be crafted in a silo, isolated from the conflicts in Europe and the Middle East. Because the crises are interrelated, so must be the responses to them. That deterrence failed in Ukraine and Israel means it stands a greater chance of failing in Taiwan. Some will argue that effective deterrence of Beijing must entail de-prioritizing U.S. support for Ukraine or Israel or other partners. No doubt, prioritization (and de-prioritization) are the essence of strategy. Given the stakes involved, along with the fact that U.S. forces would have to intervene directly and fight to prevent Taiwan’s defeat in a war, there should be little question that the preponderance of American military focus should be on acquiring the means to deter and, if necessary, defeat China in war.

But any strategy that underplays the conflicts in Europe and the Middle East risks inadvertently deepening those crises and inviting aggression elsewhere. That would leave us with more of the global “chaos” that Xi clearly values and would fuel perceptions of democratic weakness. It would be hard for even the most robust China-centric defense policy to remain credible under such conditions.

Unmistakable strength in the form of military hard power is the key to persuading China to refrain from setting off a geopolitical catastrophe over Taiwan.

There is an opportunity now to thread this strategic needle. To the fortune of democracies everywhere, the people of Ukraine and Israel have demonstrated their will and ability to fight their wars without asking any third country to sacrifice their own troops. Robust support for them by fellow democracies, through financial assistance and the provision of weapons and ammunition, would seem both economical and prudent, particularly when contrasted with the far greater costs — in lives and treasure — that would be required if either of those nations fell.

By raising defense spending (calculated as a percentage of GDP) to something closer to the average levels of the Cold War, the United States, Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and other allies can serve as a new Arsenal of Democracy, counterbalancing the arsenals of autocracy played by Iran, North Korea, and, above all, China. Using government spending to catalyze private industry in unorthodox ways could result in a rapid scaling up of munitions and armaments production, much as Washington’s 2020 Operation Warp Speed collaboration with private companies produced hundreds of millions of COVID-19 vaccines in record time.

Such an undertaking would have the benefit of resupplying our partners for their defensive wars in Europe and the Middle East, while simultaneously creating the military stockpiles needed to deter Beijing. There is evidence already that U.S. support for Ukraine has in some respects improved U.S. procurement for a war with China, by forcing the Department of Defense to kick-start manufacturing lines and replace old munitions and equipment with new inventory.

The clock is ticking. While diplomacy and public statements have an important place in a well-crafted policy of deterrence, unmistakable strength in the form of military hard power is the key to persuading China to refrain from setting off a geopolitical catastrophe over Taiwan. This is what kept the Cold War cold in the last century. This is what can keep Xi from rolling the iron dice of war in this one. ∎

Excerpted from The Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan, edited by Matt Pottinger. Copyright © 2024 by Hoover Institution Press. Reprinted by permission. This excerpt was also published at The Wire China, under the title “The Case for Deterrence.”

On July 1, join us at Asia Society in New York for a panel event with Matt Pottinger and guests to discuss the shifts in China over the past decades that have led to this moment of potential conflict in the Taiwan Strait. Register your ticket in advance here.

Matt Pottinger is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution, chairman of the China Program at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, and a former U.S. deputy national security advisor from 2019-2021. He is editor and co-author of The Boiling Moat (2024).