Ed: In Private Revolutions (Viking, 2024), Yuan Yang follows the lives of four young Chinese women as they carve their paths in life and work. Excerpted below is part of the story of one of those women: Sam, a university student reading sociology in her hometown of Shenzhen, who becomes interested in socialism and Marxism. We pick up Sam’s story when she begins graduate school, and begins to put theory into practice.

Not long after Sam arrived at graduate school to pursue a master’s degree in sociology, one of her lecturers invited her to join a departmental reading group on Karl Marx’s Capital.

Before that year of wading through the dense text, Sam had held broadly left-liberal concerns, but had yet to develop an overarching belief system. Reading Capital gave Sam her first complete theoretical framework. After a year of the reading group, Sam started calling herself a Marxist.

What her newfound Marxism entailed was less clear, because there was no recipe for revolution in Marx’s writings that suited China’s modern stage of development. Capital was a book that seemed to Sam to be simultaneously from the past and from the future. It had inspired China’s revolution of 1949, but the legacy of that revolution was at once ubiquitous and indiscernible. China had never officially renounced its Marxism, of course, but was now governed by authoritarian capitalists. If the new generation of Marxists wanted a new Communist revolution, they needed to wrestle with the question of how China could avoid repeating its own history.

For her master’s thesis, Sam conducted fieldwork in a residential compound in Shanghai that was home to the retirees of a major shipyard that was nationalized during the Communist Revolution. The former shipyard workers spoke in turns of phrase that reminded Sam of the Maoists of the Utopia forum that she had mocked in high school. Though she had thought those online Maoists ridiculous, she was moved by the accounts of the shipyard Maoists. The former shipyard union leaders spoke of the early years of the Communist Revolution with a clarity that made Sam feel the 80-year-old workers possessed a stronger sense of conviction than she had ever felt in school.

Sam’s fieldwork renewed her desire for social change, as did conversations with her classmates in the Marx reading group. One winter, they discussed the beating to death of Zhou Xiuyun, a migrant worker and mother who had been trying to get her unpaid wages, by the police in northern China. One officer had stood on Zhou’s hair for an hour as she lay unconscious on the frozen ground. Sam and her classmates railed against the injustice of a system where migrant laborers were routinely abused by their employers and treated as second-class citizens by the government. China’s workers were wealthier than they had been under communism, but they were now being exploited under an authoritarian capitalism.

In the conclusion to her master’s thesis, Sam wrote that the Communist Party of China had “already deteriorated into an exploitative elite alliance that commits massive expropriation of ordinary workers and peasants.” She argued that society needed to move “beyond the inhumanity, inequality and indignity of capitalism in all its myriad forms.” By now, Sam was not only a Marxist but had reached her starting point as a Maoist: the need for revolution.

If the new generation of Marxists wanted a new Communist revolution, they needed to wrestle with the question of how China could avoid repeating its own history.

When she graduated, Sam started volunteering as an editor for an up-and-coming left-wing blog called the New Commune. Its goal was to “unite intellectuals, workers and farmers.” Its strapline spoke of utopias and collectives, but its published content dealt with everyday concerns, such as why working overtime was so common, or how employees could combat sexual harassment in the workplace.

Sam stayed in Shenzhen, but the New Commune’s main office was in an apartment complex in Beijing, in such a remote quarter that it didn’t feel like part of the city. To get there, Sam had to take a long subway ride and an overground train to the city’s northern outskirts, where the landscape transformed from the business district’s metallic skyscrapers into low-rise apartments and dry fields of yellow grass.

It was a cozy apartment. Two of Sam’s colleagues lived in a bedroom adjacent to the office — or to put it another way, her colleagues had moved in together and turned their living room into an office. Most of the staff and volunteers were women in their early twenties. In the evenings, they ate dinner together in the living room/office, where they had two cats that played together on the floor.

Sam and her colleagues were trying to learn from political movements around the world to see what lessons they might apply to the Chinese situation. The two women who rented the flat had recently attended a conference of trade unions in Europe; they were surprised to find that they were some of the conference’s only young, female attendees.

They also learned that, in Europe, the term “left” had very different connotations from what it has in China, where it has a confusingly broad range, and can be used to refer to people who support the status quo of the Communist Party’s rule, as well as to radical Maoists like Sam. In China’s mainstream discourse, “right” refers to those in favor of democracy and free markets, and is associated with a more internationalized, younger generation. In this respect, China’s generational connotations of left and right were the opposite of what they stood for in the West: the “left” was the conservative past, and the “right” was the brave future.

Sam was interested in the history of the American labor movement, particularly the use of “salting”: the practice of entering a workplace with the goal of organizing it. She often joked that, at the New Commune, she was in “the most unradical part of the most radical movement” – the most radical edge, in her estimation, being the students who worked in factories after graduation to “salt” them. Over the course of her master’s degree and her time at the New Commune, Sam heard several rumors of students who had turned down elite employment prospects to do this work.

A small network of underground Maoist activists dedicated to “salting” had taken root in the Pearl River Delta in the late 2000s. Salting was a much more radical tactic than those adopted by most Chinese labor NGOs, which, by the late 2010s — under pressure from the government — had, in order to survive, become more focused on helping individual workers obtain medical compensation or unpaid wages than organizing workers collectively. Any form of movement-building attracted too much political scrutiny.

Sam admired the students who went to work in factories for their courage, but it wasn’t the right path for her: she didn’t consider herself tough enough. She couldn’t stand for ten hours a day on a factory line, repeating the same minuscule movements thousands of times. She also didn’t have much confidence in her ability to organize workers: her mannerisms and polite, roundabout way of speaking all betrayed the middle-class habits she found difficult to shake. Her interests and skills lay in thinking and writing, which is why her media job suited her.

Yet even this option, which she considered relatively tame, had its risks.

Sam wrote that the Communist Party of China had ‘already deteriorated into an exploitative elite alliance that commits massive expropriation of ordinary workers and peasants.’

Barely a year after Sam started working at the New Commune, the police began hounding the landlord to kick her colleagues out of their Beijing office. The police frequently used this tactic with activists they didn’t like but didn’t have enough reason to arrest. It was never clear if their ultimate goal was to drive the activists to other cities, where they would become other police forces’ problems, or simply remind them that, at any moment, the government could make their lives difficult. Sam’s blog had been hosted on the messaging app WeChat, which, by the mid-2010s, had become an all-encompassing social media, website-browsing and payments platform that comprised the majority of Chinese people’s experience of the internet.

With the rise of social media, many political blogs flourished on WeChat’s Public Accounts platform, threatening to transgress the unspoken boundaries of censorship. Some issues were clearly untouchable: the leadership’s family wealth, for instance, and issues related to territorial integrity, like the future of Taiwan. But throughout the 2010s, the areas of sensitivity multiplied to the extent that editors could no longer predict the government’s reaction to any piece of media with much accuracy.

It was common even for established newspapers to have an article blocked now and then. It was more devastating when an entire account was suspended for a period, although independent media outlets could weather these suspensions if they were relatively brief and they could hold onto their audience of dedicated readers. Sometimes, though, the consequences were more serious: in the spring of 2016, the labor news blog New Generation was permanently shut down after reporting on a strike of thousands of miners in China’s post-industrial north-east, all of whom were owed wages by their state-owned enterprise.

Unlike New Generation, Sam’s colleagues at the New Commune didn’t cover breaking news; they mostly posted commentary and analysis from a Marxism-tinged perspective aimed at a young readership. But in the summer of 2016, they, too, were shut down by the online censors.

After a few months, Sam and her colleagues launched a new blog and attempted to recover their old readership. They printed tote bags bearing their new name, Today’s Collective, and mailed them to their former subscribers. They had had to relocate their office, but their underlying pattern of writing and editing gave the team stability: whatever the circumstances, new posts had to be published and commissioned every week to maintain readers’ interest. Eventually, the media outfit even secured enough funding to pay Sam a salary, although it was only a little more than what a delivery driver could make in Beijing. After living on a scholarship of 12,000 yuan ($1700) per month during her master’s degree, Sam was earning 5,000–6,000 yuan ($700-$850) per month at the blog.

Sam opened their next office in Shenzhen. She shared the room with a young woman from another blog aimed at educating factory staff about workers’ rights. Sam lived quietly in the office on the outskirts of her home city. She liked to take long walks along the harbor front facing Hong Kong. She saw a traditional Chinese medicine doctor to treat her easily inflamed skin, and carefully brewed her herbal prescriptions every day. When she wasn’t editing, she was reading Buddhist scriptures, Marx or Lenin.

Later on, a more serious threat than the police approached one of Sam’s colleagues — state security officers, who deal with matters of national importance. They didn’t ask about Today’s Collective, but the state security’s presence in Sam’s circles shocked them all. It showed them that they were on the edge of something the government considered dangerous.

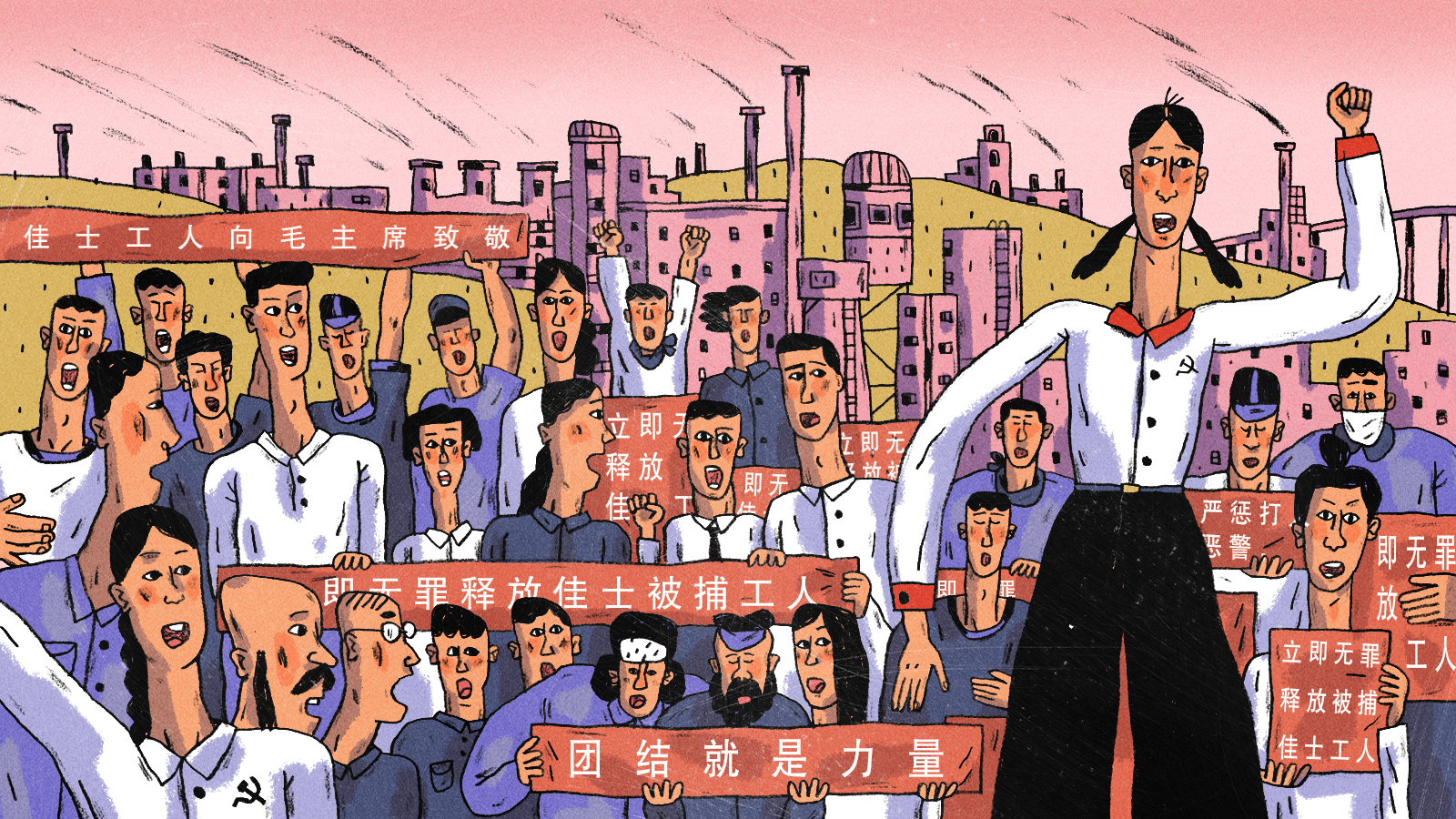

In the summer of 2018, Sam started noticing articles on the various leftist social media accounts she followed about an unusual coalition of workers and students protesting in her home city.

In May 2018, Mi Jiuping, a worker at the Jasic Technology electronics factory in Shenzhen, had petitioned the factory to allow workers to unionize. Jasic’s management, of course, refused to approve the application. In July, they retaliated by firing Jiuping and two fellow organizers. Undeterred, the workers tried to enter the factory again, at which point the management called the police. Jiuping and his fellow organizers spent a night in police detention. Their supporters protested outside the local police station — an unusually confrontational tactic. They, too, were detained for a night.

By this point, news of the labor dispute had filtered through the networks of Maoist activists into the broader communities of Marxist students across China’s universities, some of whom started making their way south to Shenzhen.

A week later, on 27 July, Jiuping and his colleagues staged another protest outside Jasic. The police arrested 30 people, including one student activist, in what became the largest mass arrest of workers in three years. The next day, the Marxist students published an open letter calling on the local government to release the detainees.

Sam was impressed by their courage and the speed of their coordination and, feeling she had a duty to support them from afar, amplified their letter on her blog. Students flocked to Shenzhen and set up base in a rented dormitory in the city, calling themselves the Jasic Workers’ Support Group.

Some of the students set about recruiting more students and supporters to come to Shenzhen. Others spoke to journalists, using media contacts shared by the broader, looser community of labor activists. Some devised plans for warding off their teachers and parents. At first, the police attempted to pressure the students by flying these guardians to Shenzhen and putting them up in hotels, where they would try to convince their children to abandon their campaign.

The students wore T-shirts printed with the black-and-white silhouettes of five arrested Jasic workers on the front. Below the image, in red lettering, the shirts declared ‘Unity is Power’; the back read ‘Jasic Workers, Stand Up, be Your Own Master, Establish the Union’.

One of the movement’s most prominent student activists, Shen Mengyu, raised money to cover the group’s legal costs through a WeChat crowdsourced payment page. Since all WeChat and bank accounts require verification, her real name was attached to her work. On the evening of 11 August, as she walked out of a restaurant where she’d had dinner with her parents, men in plain clothes seized her and forced her into an unmarked car.

At daybreak on 24 August, riot police stormed the students’ dormitory and arrested the remaining fifty or so students, marking China’s biggest student crackdown since Tiananmen Square. As the police searched their belongings, the students linked arms and sang the socialist anthem, the Internationale.

Later that day, a state media journalist for Xinhua News published a story accusing the students of being part of an illegal campaign controlled by foreign forces.

Sam was impressed by the workers’ courage and the speed of their coordination, and felt she had a duty to support them from afar.

The crackdown on the Marxist students extended into the start of the academic year, at which point university administrators joined police in urging the students to abandon their activism. Pressure soon turned, once more, into violence: in November, an unmarked car drove into the campus of Peking University. Men wearing plain clothes grabbed two recent graduates who had been involved in the Jasic support group, beat them and dragged them into the car. The arrests of students and activists spanned five cities in total, stretching from Beijing to Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Shanghai and Wuhan.

In a surreal twist, China’s top universities began banning their student Marxist societies. At Peking University, where Mao Zedong had once worked as a librarian and met with Marxist students in the late 1910s, the university administration replaced the Marxist society leaders with loyal party members. Overnight, a group that had once organized cleaners on campus became a study group for the sanitized government ideology of Xi Jinping Thought.

On a frosty late-December morning, Peking University’s ousted student Marxist society leaders protested outside the university’s Department of Marxism, linking arms to form a human chain. Teachers and guards wrestled them to the ground. For the rest of that day, the students were detained inside the same sociology classrooms that had hosted the labor studies summer camp Sam had attended years earlier.

After the arrests, some of the student activists were held in police detention centers, then released. Others disappeared into China’s system of ‘black jails’, a network of extralegal detention centers reserved for those deemed threats to state security, officially called ‘residential surveillance at a designated location’ (RSDL). Police often hold detainees for up to a month before notifying their family members and up to six months before informing them of their crimes. In RSDL, solitary confinement is a typical punishment, as is leaving bright lights on constantly to deprive the victim of sleep.

Both in the detention centers and in the black jails, the officers tried to manipulate the students to make scripted confessions, intimidating them one moment, then offering friendly, patronizing advice the next. The officers assumed that everyone could be bought for a certain price or with enough force, even if that meant resorting to torture.

In January, police showed the Marxist students who had been released a video of those still detained. The students thought that the faces of their imprisoned colleagues looked swollen and colorless, their expressions unnatural. One male student said to the camera: “In our student society, we talked about the sixty-year history of the People’s Republic of China . . . We exaggerated the beauty of the first thirty years after the revolution and the problems of the past thirty years after Reform and Opening Up. We were given a wrong view of history.”

A well-trained male news anchor’s voice suddenly blared over the video: “They used to think that China was not a socialist society, didn’t approve of the current political system, and wanted to achieve so-called socialism through a student and workers’ movement. After a period of reflection, how have their views changed?”

A female student said: “Now that I have been educated by the police, I truly understand China’s national situation, in particular that, since the 18th Party Congress [when Xi Jinping was named as president], the party and the government have used many concrete methods to fight inequality.”

Shen Mengyu, the prominent activist who had been bundled into an unmarked car, said: “Our actions constituted illegal crimes, which not only seriously disturbed the social order, but also caused some foreign forces to use this incident to attack the party and the government, severely tarnishing China’s international image.”

The male student spoke again: “Reform and Opening Up . . . was the correct developmental path, combining Marxism with China’s special characteristics.”

A third female student’s testimony concluded the video: “I will not only stand with my motherland and its people, I will stand with the party.”

In a surreal twist, China’s top universities began banning their student Marxist societies.

As the months wore on, the police detention effort expanded to entrap other labor organizers, social workers, factory workers and NGO staff in the Pearl River Delta with no direct relationship to the original Jasic protests. The government seemed to be bluntly retaliating against the broader community of labor advocates.

Sam heard of more and more friends in her leftist circles being detained. The disappearances that hit her hardest were those of Wei Zhili and Ke Chengbing, who had co-edited the prominent labor issues blog, iLabour. She had admired their work, and had met up with them many times. While she was writing for Today’s Collective, she had asked them for help on stories about the migrant workers who had built Shenzhen’s skyscrapers and, as a result, were now dying from the lung disease silicosis.

She started feeling a mixture of paralysis and urgency for action. She thought that all she could do was show solidarity, but that was not enough. She eventually gave up nearly all her work at Today’s Collective to focus on helping the student activists. (The blog had become less active anyhow, as many of its contributors were similarly absorbed by the student activist movement.)

With her media experience, Sam was chosen by an organizer within the movement to become one of the intermediaries between the students and the media. They needed someone to absorb the risk of being in touch with ‘foreign forces’.

The organizer who had recruited Sam commanded a great deal of trust among the students. That meant Sam in turn was trusted, although nobody knew her name, and she knew very few other people’s. That was one of the many rules of privacy that this band of underground activists used to keep themselves safe. But such rules also increased the isolation of its members, as well as the power of those higher up its hierarchy who knew more about what was happening within its structure. When she went for walks on her own, Sam would dwell on the thought that the things she did for the movement weren’t front line enough.

In the spring of 2019, she pivoted to providing immediate support for the labor activists who were being detained. She contacted their family members to ask about the circumstances of their disappearances and, if she could locate the activists, organized donations of money and food. She also looked for lawyers who could contact state security and pursue information about the activists’ cases. Because very few human rights lawyers remained active in China after a wave of mass arrests in 2015, Sam sometimes resorted to hiring ‘street lawyers’, the kind who waited outside detention centers to offer their services to desperate clients.

Sam’s sense of urgency slipped towards despair and then apathy. When she talked to her friends in the movement, she rarely brought up her growing sense of depression. It wasn’t that she didn’t talk about problems with her friends at all – she still fought to hold on to some of her old self- deprecating humor. It was more that, in her mind, the major struggles – politics and its burdens – lay outside the realm of everyday griping and commiseration. When she did talk about the worsening political situation, it was with resignation. ∎

Adapted from Private Revolutions by Yuan Yang, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 Yuan Yang.

Yuan Yang (杨缘) is a British-Chinese politician, economist and journalist. She is serving as Member of Parliament for Earley and Woodley since 2024, for the Labour Party. Yuan is a former columnist and Europe-China correspondent at the Financial Times, and cofounder of the charity Rethinking Economics, which campaigns for a more diverse and realistic economics curriculum. She is the author of Private Revolutions: Four Women Face China’s New Social Order (Viking, 2024).