When pivotal moments in Chinese history have been captured in photos, such as 1989’s Tank Man (the famous protestor who stood down a tank during the Tiananmen massacre) or 1937’s Bloody Saturday (a soot-covered baby crying in the streets of bombed-out Shanghai), the photos themselves have become images of cultural significance. Such photos, along with those of Mao Zedong swimming the Yangtze in 1966, or Richard Nixon eating with chopsticks next to Zhou Enlai in 1972, established photography as a crucial force in chronicling China’s modern history and social evolution.

The camera has also served to document the beauty of China’s natural and manmade landscapes, and as an anthropological tool, recording the lives of Chinese from all walks of life since the 1800s. In the last few decades, Chinese contemporary artists have also put their eyes behind the viewfinder, offering powerful social commentary through an artistic aperture.

This list presents five recently published photo collections. A war correspondent in the late 1930s documents his flight from the Imperial Japanese army in wartime China. A curated history traces how Chinese photography has evolved from Mao to now, just as a collection of images from 1980 capture the country’s nascent economic reform. A New York Times photo editor captures the imposing architecture of Hong Kong, while on the outskirts of the city, a former cartoonist documents village life. From high-art head-scratchers to in-the-fray war photography, these books connect the historical and artistic threads of China photography, and bear testament to the power of the lens in interpreting the nation’s changes.

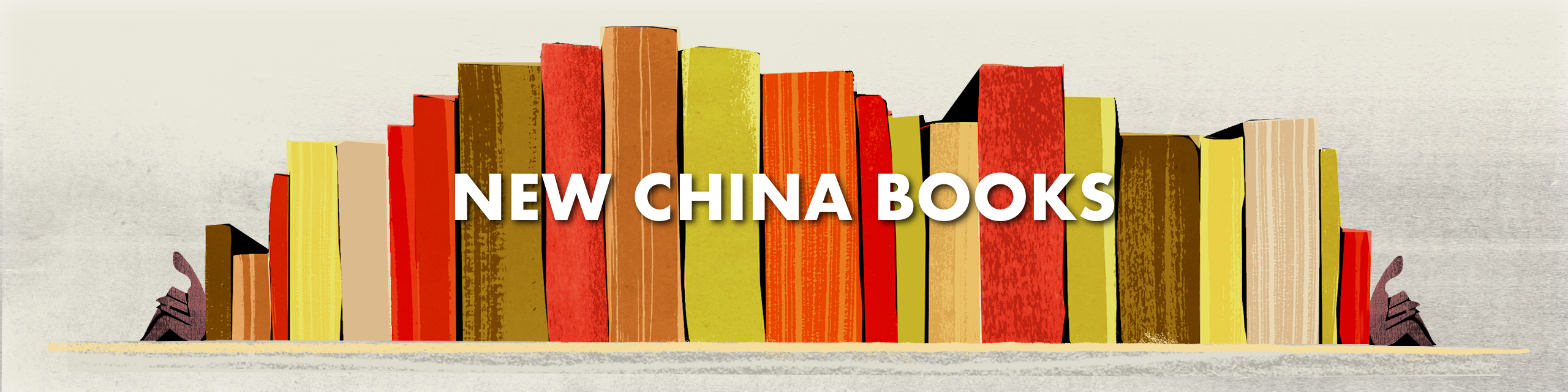

A Danger Shared

A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War

Time Magazine war correspondent Melville Jacoby reported from China and parts of Southeast Asia from the mid-1930s until 1942, when an erratic fighter-plane veered off of an airstrip in Australia and crashed into Jacoby, killing him. Along with his newlywed wife Annalee (co-author of the acclaimed 1946 book Thunder Out Of China), Jacoby covered World War II in the Pacific, and had unparalleled access to Republican China. Portraits of peasants share the page with intimate pictures of Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Mei-ling (the latter seen doting over orphans on a political outing). But as the Japanese bore down on China, Melville and his wife were forced to flee their posting. Through his camera, Jacoby documents their perilous flight southward to Australia via Manila, capturing the brutalities of the unfolding war along the way. One particularly jarring photo, of bodies strewn across a Chongqing staircase by Japanese bombs, caused public consternation when Time published it for U.S. audiences. A Danger Shared is both a powerful glimpse of World War II China and a riveting piece of gonzo journalism, as Jacoby documents the personal journey that preceded his own tragic end.

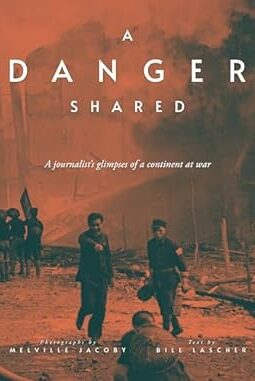

China 1980

Pictures From Another Era

In 1980, China’s Reform and Opening period had already begun, but the nation was still decades away from becoming the modern powerhouse we are familiar with today. That year, Australian photographer Mike Emery took the first cruise along the Chinese coast since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. He took snapshots of ordinary life where the liner stopped off, in Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai. Emery later compiled over 200 photographs into this collection, showcasing China at a time when its culture, politics and fashion trends were a gradient between the collectivist Mao era and the showy individualism of 1980s capitalism. Plastic heels are as ubiquitous as proletariat caps. One subject wears a People’s Liberation Army jacket with a pair of jeans. A line of elderly men in formal wear turn their heads to gawk at a woman in shorts and sunglasses. A man in an ill-fitting Western suit walks arm-in-arm with a young woman sporting a showy hairdo. China 1980 captures a pivotal moment when Chinese citizens, free to pursue their material desires, first set off in doing so.

Chinese Photography

Twentieth Century and Beyond

A comprehensive history of Chinese photography from the Republican era to the present, this is the ideal starting place to understand the work of modern Chinese photographers. Rong Rong is himself a renowned photographer, with works displayed in the MoMA and National Portrait Gallery. Each photo is accompanied by Rong Rong’s short analysis of its significance, and the volume is interspersed with ten essays on photographic art history and criticism. The collection’s early pages feature images of hard times and war-torn landscapes; the middle chapters display the military uniformity of the Mao era; and in the final chapter, during the reform era, photography transforms from a documentarian practice to an artistic medium, often abstract or backwards-looking. There is no better source for understanding the significant moments and movements in the history of the medium in China.

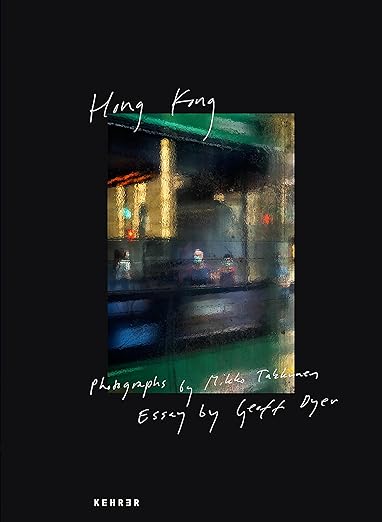

Hong Kong

This collection of artfully composed photographs, by The New York Times Asia photo editor Mikko Takkunen, shows a city in limbo. Takkunen lived and worked in Hong Kong from 2019, when Hong Kong’s streets were flush with protesters, to 2020, when they were emptied by draconian Covid policies. Hong Kong is Takkunen’s compiled work from this transitional period, depicting a Hong Kong characterized not only by political upheaval but also by a quieter angst. The city through Takkunen’s lens is a near-deserted technicolor metropolis of neon beauty, and Hong Kongers often appear dissociated, even morose; their figures are small in Takkunen’s framing, dominated by the city’s towering skyscrapers. These empty shots, taken in one of the world’s most densely populated places, capture a feeling unique to the Covid era: isolated life in a chaotic world, as if in the quiet eye of a storm. Hong Kong is both a photographic tour de force and a time capsule from a unique historical transition.

The Village at the Center of the World

Former South China Morning Post cartoonist Larry Feign, who retired to Wang Tong on Lantau Island, captures a very different, rural experience of life in Hong Kong in The Village at the Center of the World, his idiosyncratic foray into photography. Feign pairs his photographs with short essays about aspects of life in Wang Tong, a village of just 70 homes and 250 residents. The vignettes are short, and as disjointed as the photographs. A simple photo of a local dive bar is followed by an aerial shot capturing the whole village, then soon after, a close-up of the author’s overflowing gardens. Feign’s images have an understated style that reflects the author’s charmingly slow pace of life; he spends his time listening to jazz, meditating, and tending to his garden. The essays and pictures of The Village at the Centre of the World lack a central narrative, but are bound by a Walden-esque seclusion, and an endearing simplicity that mirrors that of life in Wang Tong. ∎

Alex Mormorunni is a senior at Vanderbilt University, and interned with Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations in New York, assisting on China Books Review. His articles have appeared in The Tennessean and Vanderbilt Political Review, where he is Deputy Editor-in-Chief. He is an undergraduate political science researcher on US-China relations, and a copy-editor for the Vanderbilt Undergraduate Research Journal.