For China, 2024 was a year of recovery. On the surface, the routines of life were restored in the wake of the Covid pandemic and economic downturn. Various policies were introduced to reinvigorate the economy, new TV series and reality shows trended online, and public debate around topics such as feminism remained as lively as ever. Yet, to a degree, these bubbling noises only amplify the silence at the center of the nation’s consciousness — the lack of reflection on the pandemic and the erasure of the past three years from collective memory. People trudge forward without speaking of what happened.

Signs of resistance emerged quietly, through the act of writing. 2024 has been a notable year for publishing in mainland China, with some books shedding light on how the past few years have reshaped lives and minds. What happens when a society, post-trauma, is not allowed to openly discuss its experiences? To explore this question, we turned to the popular end-of-year book list by Douban, a Goodreads-like Chinese website which highlights its favorite books of the year across fiction, nonfiction and poetry. From their list, we chose five intriguing titles, each offering its own response — whether directly or indirectly — to the not-so-distant past.

Normal Contact

正常接触

This collection, the fourth book by acclaimed short story writer Wang Zhanhei, was largely written during the pandemic. During that time, Wang joined her neighbors in delivering medicines and groceries to those most in need within their Shanghai neighborhood. When the Zero Covid policy was eventually lifted in late 2022, and test tents vanished as if they had never existed, Wang found herself consumed by anger and resolved to bear witness to what had happened. Each story is infused with the staleness of days and weeks spent indoors. In one, an unemployed man takes on a gig feeding pets for quarantined strangers who are unable to return home. Another is an epistolary story addressed to a fictional character based on Wang’s neighbor, who jumped from his apartment window during the Shanghai lockdown. How soon is too soon for writers to respond to a historical event? While some readers have found these stories less polished than Wang’s previous work, others have drawn solace and strength from the silent monuments of her words.

Runaways

逃走的人

“I don’t want to live in stress. I want to lie flat. I want an easy life.” So said one young woman profiled in this book who moved to Hegang, a down-on-its-luck former industrial city in Northeast China’s equivalent of the rust belt. In recent years, however, cities such as Hegang have been gaining popularity among young people who are fed up with the long working hours and high cost of living in big cities. In 2021, GQ China contributor Li Yingdi became intrigued by this growing community of “modern recluses.” What drove them to adopt this lifestyle? Was it sustainable? Did they find freedom or happiness? Li moved to Hegang herself in 2022, where she met several members of the community. As winter wore on, her fellow recluses let their guards down and shared stories from their past lives — a sailor, an iPhone assembly line worker, a call center representative. Written in succinct prose, this fascinating book chronicles Li’s time among these “runaways,” as they reflect on the deeper meaning of their existence and the extent to which one can truly be free.

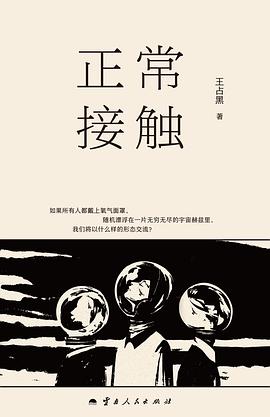

Why Do We Need Libraries?

世上为什么要有图书馆

Voted Douban’s Best Nonfiction Book of the Year, Yang Suqiu’s Why Do We Need Libraries? chronicles the journey of a literature-professor-turned-government-official building a public library from scratch. As part of a uniquely Chinese exchange program between higher education institutions and local governments, Yang served for a year as deputy director of the Bureau of Culture and Tourism in Beilin, a district of Xi’an. In engaging detail, she vividly recounts her experience, relating the challenges she and her team faced, from book selection to construction logistics. What elevates this book above mere propaganda is Yang’s unique perspective as an outsider. Without political ambitions, she maintains a critical distance from bureaucratic rituals, reflecting on both the allure and the dangers of power, however minor they may seem. While the book’s publication suggests it doesn’t cross political red lines, this does not detract from its value. For too long, government operations have been a black box. Yang sets an example for everyone — whether inside or outside the system — to make a meaningful difference within their capacities.

Swan Hotel

天鹅旅馆

A live-in nanny named Yu Ling conspires with her boyfriend to kidnap the son of her wealthy employer for ransom money. As she embarks on this kidnap, disguised as a “spring picnic,” news breaks that her employer’s father, a high-ranking government official, has been arrested. Overwhelmed by guilt and confusion, Yu aborts the plan and returns the boy to the family’s empty mansion. While waiting, Yu reflects on her past as well as her complicated relationship with the boy’s mother. Nine years after her last novel Cocoon (茧), which was translated into English in 2022, novelist Zhang Yueran returns with a masterful page-turner. Though Swan Hotel is relatively slim at 229 pages, it may be Zhang’s finest novel yet. Brimming with incisive observations about class, wealth and power in contemporary China, the story vividly explores how these forces shape and distort relationships between the haves and have-nots. The English translation, Women, Seated, is set to be released this August, translated by Jeremy Tiang.

Catfish

猫鱼

In Shanghainese, a “catfish” (猫鱼) refers to a small fish commonly used to feed cats. In the titular essay of this collection, acclaimed Chinese-American actress Chen Chong, or Joan Chen, recounts a childhood memory of a catfish frozen in a bowl of water miraculously coming back to life after the ice melted. For Chen, writing about her past feels like reviving frozen memories. The result is a hefty collection of autobiographical essays that intertwine Chen’s celebrated acting career (with roles in movies including Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor, Jia Zhangke’s 24 City and Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises) with her equally eventful family history. With sensitivity and candor, Chen remembers the poignant moments of her divorce, her mother’s death, and her grandmother’s difficult decision to trade sex for protection for her children during wartime. A rewarding read for lovers of both movies and words. ∎

Hailing from Chengdu, Na Zhong is a New York-based fiction writer and literary translator. Her work has appeared in Guernica, A Public Space, Lit Hub and others. She co-founded the bilingual creative community, Accent Society, and co-hosts the Mandarin literary podcast 跳岛FM. Na is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, and a 2023 MacDowell Fellow.