Reviewed: Shanghai, Joseph Kanon (Scribner, 2024)

Interwar Shanghai, with its jazz, gangsters and art-deco modernism, remains a honeypot for both fiction and literary non-fiction authors. The Paris of the East, Chicago on the Huangpu, Whore of the Orient — it’s irresistible to both Chinese and foreign writers. But after nearly a century, what responsibilities do authors have to get old Shanghai right, to reveal its nuances and complexity? In short, to do their research, lest cliché overtake the already thrilling truth.

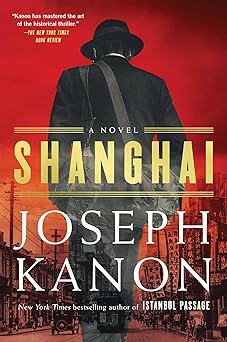

The bestselling American author Joseph Kanon has built a reputation since the late 1990s for writing atmospheric historical thrillers set just before or just after World War II. His range has always been broad — the Manhattan Project, the McCarthyist witch hunts, Cold War Moscow, post-war Berlin, and that infamous interwar nest of spies, Istanbul. In his latest thriller, Shanghai (Scribner, 2024), he harvests the fertile terrain for intrigue that is late-1930s Shanghai. A cosmopolitan, polyglot enclave where spies, adventurers, refugees and criminals congregated, notions of law were lax and moral compasses askew, old Shanghai already has all the stuff of fiction.

It’s also a tricky subject to master. The historical moments Kanon has covered in the past are all fairly straightforward compared to Shanghai in the late 1930s. The city was subject to foreign concessions that brought about complications including extraterritoriality (the notion that foreigners stand above Chinese law), the administration of the International Settlement and French Concession, and the refugee sprawl of Hongkou district. All the while, the Japanese army occupied the Chinese-administered parts of the city.

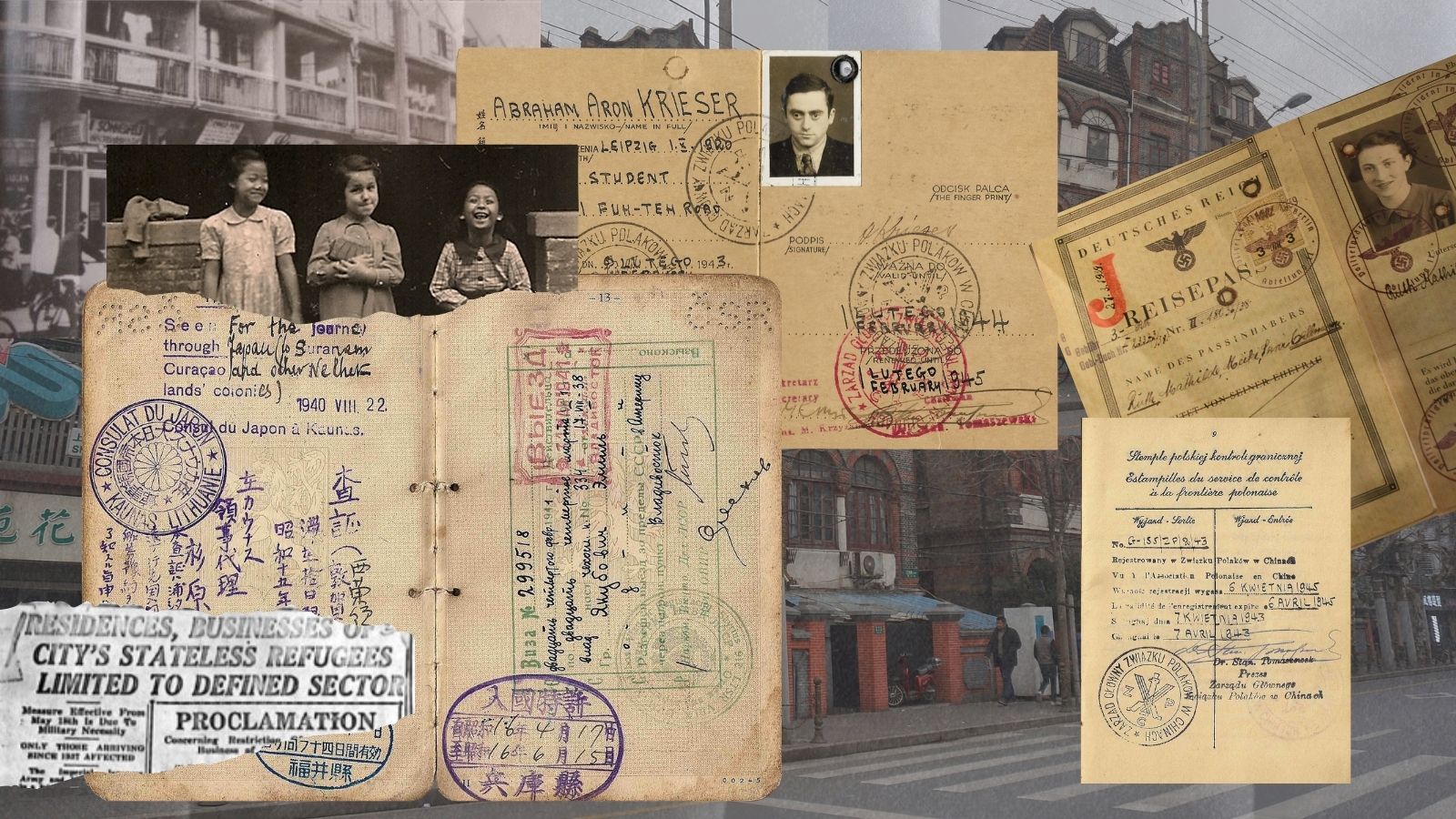

In particular, Shanghai had become a refuge for European Jews, who found an unexpected bolthole from Nazism there in the late 1930s. The great conundrum of Shanghai — as Chinese internal migrants, émigré White Russians and escaping Jews all found — was that a city seized by gunboat and grown fat on imperial plunder could be a land of opportunity, or a port of last resort. It was a chaos of extremes: great fortunes were made while the poor and exiled died of hunger, tuberculosis or gunshot.

The plot of Shanghai involves a young, anti-Nazi Jewish refugee, Daniel Lohr, arriving from Berlin having met a fellow exile, Leah, onboard the ship from Trieste. When they land in Shanghai, Leah heads to the growing Jewish “ghetto” in Hongkou, while Daniel finds his uncle Nathan, who has reinvented himself as Nate Green, a nightclub-running gangster. Daniel dives into a Shanghai of narcotics, gambling and prostitution; of intelligence agents playing games of cat and mouse with the encroaching Japanese, whose interests often overlap with the criminal underworld. Leah moves between the Jewish Ghetto (also called the Shanghai Ghetto) and the Settlement-side demi-monde — though Kanon never really fleshes out the former, preferring to center the action among the city’s international crowd.

The book has all the ingredients of a typical Shanghai novel of the 1930s. Shanghai was always a city of reinvented pasts, and Nate is but one of many immigrants born again by the Huangpu River. Pudong wharf rats became gang bosses; Baghdadi traders became wealthy merchant princes. It was a city inundated with ex-cons, remittance men, AWOL Marines, rapacious Japanese, embattled Chinese and assorted ne’er-do-wells. Yet in Kanon’s rendering, the east-west fusion of Shanghai, its cheek-by-jowl of wealth and poverty, fails to gel.

A polyglot enclave of spies, adventurers, refugees and criminals, old Shanghai already has all the stuff of fiction.

In Kanon’s previous thrillers a sense of underlying fear and tension is palpable, but this suspense is lacking in Shanghai. Readers seeking a tale of the Shanghai Ghetto will also find historical information sparse in the novel, despite its marketing. The vast majority of the action takes place in Shanghai’s central Settlement and out west toward “the Badlands,” yet it’s hard to get the bearings of old Shanghai at all. Real places pepper the book — Del Monte’s, Ciro’s, The Cathay Tower — mixed in confusingly with fictional locations. We get no intimation of the history that created the International Settlement or allowed Jews to come to Shanghai in the first place, let alone the city’s complex relationship to the rest of China, or the brutal war with Japan raging just outside it. Kanon’s Shanghai feels like a strangely denuded and confusing city, mostly devoid of Chinese.

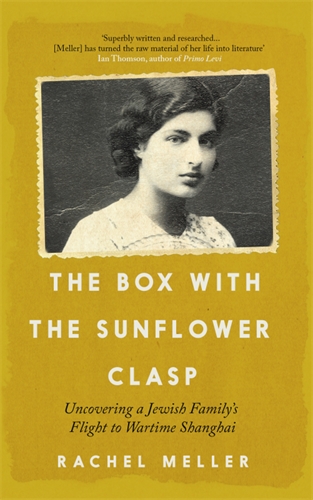

Kanon’s book adds to a shelf of titles that deal with Jewish Shanghai. There are memoirs and family histories, such as Rachel Meller’s The Box With the Sunflower Clasp (2023) which reveals the tangled lives of a Jewish family struggling for survival in the Ghetto, as pieced together from letters and photographs discovered by their descendent. Then there are novels, like Juliet Conlin’s The Lives Before Us (2019), about two young Jewish women who flee to Shanghai to escape the Nazis. More controversial titles include the French novelist Marek Halter’s La Juive de Shanghai (The Jew From Shanghai, 2022), as yet untranslated into English, which attracted criticism for its cover featuring a woman, supposedly in 1937 Shanghai, wearing traditional Vietnamese clothes. Or there is Weina Dai Randel’s novel Night Angels (2023), which fictionalizes a meeting between Ho Feng-Shan, the Chinese diplomat in Vienna who helped thousands of Jews escape to China, and Nazi official Adolf Eichmann.

When dealing with a subject as complex as Jewish refugees’ status in Shanghai during World War II — described by The New York Times in 2019 as a “secret history” — readers may care to know what is and is not true. Kanon’s recreation of 1930s Shanghai is generally historically accurate, though he provides no bibliography or sources. At the risk of sounding churlish, I even spotted a couple of details drawn from my own book on the period, City of Devils (2018), about an outlaw American, Jack Riley, who became the Slots King of Shanghai, and a Jewish refugee, Joe Farren, who opened nightclubs, whose “chorus lines rivaled Ziegfeld’s,” according to the publisher’s blurb. Here are the throw-away lines of dialogue from Kanon:

Joe Farren’s going to open a new place in Great Western Road, a monster, even for him. Big floor shows. A Ziegfeld. … Jack Riley, he runs the slots. You have gambling, you have squeeze. It’s the way it works.

These are what another writer of historical fiction, Colm Tóibín, described in a literature festival panel as the “sheep’s droppings” of creating place, building out a novel’s world. Alan Furst, another author of espionage novels set largely on the eve of World War II in Europe, advised historical novelists to extensively research their subject, then to throw everything against the wall and see what sticks. The trick was to explain just enough, offering sufficient flavor and texture without a novel becoming a list of historical details that pull the reader out of the plot.

Kanon’s Shanghai feels like a strangely denuded and confusing city, mostly devoid of Chinese.

Novelists and literary non-fiction writers tread heavily in the footsteps of academic work. Many of the details in City of Devils, in turn drawn on by Kanon, come from American Sinologist Frederic Wakeman’s groundbreaking studies Policing Shanghai (1995) and The Shanghai Badlands (1996), Andrew Fields’ essential Shanghai’s Dancing World (2010) and Lynn Pan’s Old Shanghai (1984), not to mention time spent in the archives with old newspapers. One fictional character in Kanon’s novel, the wealthy American hostess Florence Burke, is surely based on the real-life rich society maven Bernardine Szold-Fritz — who was the subject of a fascinating 2023 biography by Susan Blumberg-Kason, Bernadine’s Shanghai Salon. Without this cascade of influences, a book like Shanghai could not have been written with convincing historical detail.

Shanghai of the late 1930s was a liminal space. Its foreign-controlled quarters were surrounded by a ravaging Japanese army while the concession’s rule of law, policing and social fabric fell apart. The old guarantors of Shanghai — foreign gunboats, troops, a functioning police force, civic institutions — had all, or in part, disappeared. The city became a “solitary island” (gudao), as the International Concession was once called, and sunk into a feral state of dog-eat-dog criminality. Within that larger island was the smaller Jewish islet, encompassing billionaires and paupers, rabbis and violin virtuosos, prostitutes and gangsters.

Daniel, Leah and the other refugees in Kanon’s Shanghai find themselves escaping the frying pan only to find themselves in the fire. Yet the novel is, for my money, a little bland and sparse — what we might term “Old Shanghai generic.” As living memory passes and the last denizens of Shanghai’s Jewish Ghetto die — just as troves of their photos and letters found in old biscuit tins in attics become ever rarer finds — our recreations of the period will become solely fictional. That makes it even more incumbent upon authors to get it right, and to acknowledge those who laid the foundations their fiction is built on. ∎

Paul French lived in Shanghai from the 1990s to 2014, running the market research publisher Access Asia. He is the author of Midnight in Peking (2012), a New York Times bestseller, City of Devils (2018) and other titles. His most recent book is Her Lotus Year (2024).