Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: Taiwan Travelogue by Yang Shuang-zi, tr. Lin King (Graywolf Press, November 2024).

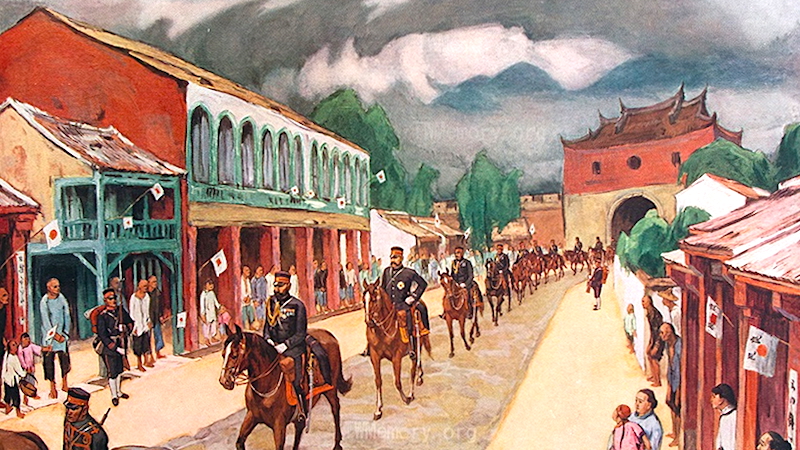

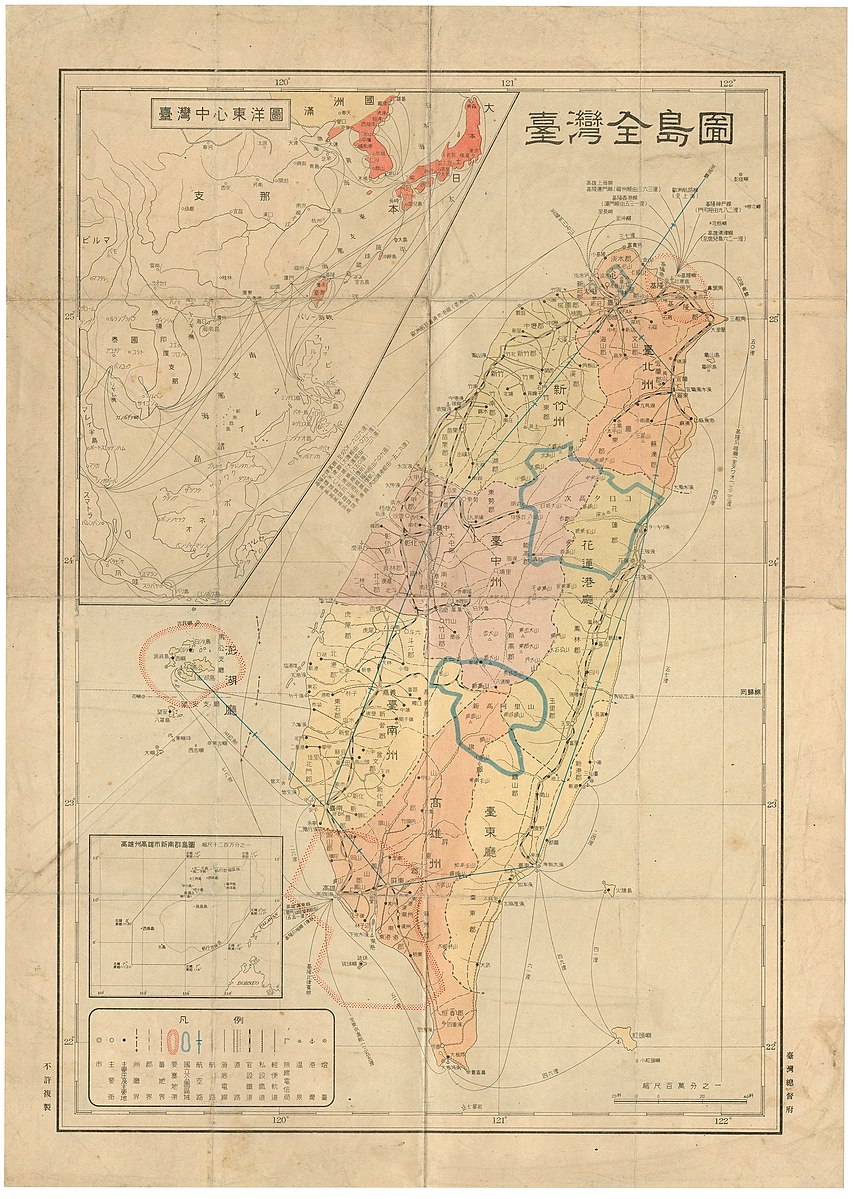

In Taiwanese author Yang Shuang-zi’s Taiwan Travelogue, which won the 2024 National Book Award for Translated Literature, China’s empire is dead and Japan’s has risen. The novel, translated beautifully by Lin King, is set in 1938, by which time Japan had already conquered roughly 3 million square kilometers of Asia. Its protagonist, Aoyama Chizuko, is a Japanese writer who travels to Taiwan to give a series of talks.

On the sub-tropical island, Japan’s southernmost conquest in the Pacific, hailed as her empire’s “model colony,” Aoyama becomes enamored with her brilliant, reserved and dimpled Taiwanese interpreter, Ō Chizuru, whom she nicknames “Chi-chan.” Chizuru cooks mouth-watering local dishes; speaks Japanese, Mandarin, Taiwanese and a bit of French; and meticulously arranges Aoyama’s schedule. Chizuru is engaged to be married, but Aoyama tells her to break it off and abscond to Japan with her. “Why do you accept this fate?” she asks bluntly. “You have things that you want to pursue — things that have nothing to do with marrying a man.”

Does Chizuru like Aoyama back? This question propels the plot and had this reader turning pages late into the night. The answer is never clear, as Chizuru conceals her true feelings; the word “mask” appears 33 times in the text. The story is written from Aoyama’s perspective, which amplifies the sense of Chizuru’s inscrutability. Aoyama constantly guesses what Chizuru wants and likes, dislikes and needs. In turn, Chizuru declines to give straightforward answers to even basic questions: Where are you from? Who raised you? How do you know so many languages?

Is a colonizer’s delight in local food innocuous, praiseworthy, nefarious, or all of the above?

Their relationship — of detective and mystery, pursuer and pursued, colonizer and subaltern — reflects a complex dynamic of power. As an employer, Aoyama crosses boundaries, to put it mildly. She pops a lychee into Chizuru’s mouth, expects Chizuru to cook for her all the time, purchases a luxurious kimono and asks her to wear it, and offers repeated, sometimes excruciating bids for friendship.

This may make Aoyama sound dominating and obnoxious, but she is also sincere and charismatic. The pair bond over literature, recite beloved classical poems to one another, instantly recognize each other’s literary references, and devour delicious food together. There’s a marvelously erotic scene when, on returning home from a storm, they wipe rain droplets off each other’s faces. Perhaps most poignantly, Aoyama recognizes and delights in Chizuru’s intellectual gifts, deducing early on her secret dream: to become a translator of novels.

At times, it seems that Chizuru genuinely respects Aoyama. For instance, Aoyama says that lóo-bah (滷肉饭) — a Taiwanese comfort food of braised minced pork and rice that is still beloved today — is as exquisite as sashimi. Moved, Chizuru replies, in a low voice, that the Japanese impose moral distinctions between cultures, deeming Taiwanese food “dirty” and their own food “pure.” As she puts it:

I’ve heard people say that Mainlanders [Japanese] think lóo-bah has a displeasing stench, and I have also been warned that Mainlanders only eat sashimi. But Aoyama-san seems to regard lóo-bah and sashimi with equal esteem.

Aoyama replies with surprise, saying that she has never felt Japanese and Taiwanese foods are unequal. In turn, Chizuru praises her taste as a moral choice, indeed as evidence of virtue: “That is because Aoyama-san is a good person.” Still, Chizuru’s words often contain double meanings, or what Aoyama calls “mischief.”

Nowhere is this doubleness more evident than when Chizuru attempts to resign from her job. She won’t say why, which further infuriates Aoyama. “Not a single person in your future husband’s family nor your own family is really invested in your happiness,” explodes Aoyama. “Am I right? So, pray tell me, what reason do you have to leave my side?”

“Ah—you are quite right,” replies Chizuru. “Aoyama-san is perhaps the only person in the world who treasures me as an individual.”

Is the subaltern being sincere, ironic or bittersweet? To treasure a person is also to lay a claim on them. Recognition liberates, but it also binds.

If Chizuru is slippery, so too is Aoyama. In a rare moment of candor, Chizuru refers to a “blind spot” of Aoyama’s but declines to say more. We wonder if Aoyama’s obsession with food might hint at that blind spot; she cannot stop talking or thinking about it. When she eats chikuwa, a cakey mix of fish paste and potato starch that remains ubiquitous in present-day Keelung, she announces it is to the “Empire’s credit.” Another interpreter confronts Aoyama: “The way you talk about the Island’s flavors doesn’t sound like you’re appreciating them for being delicious but rather for their exoticism—like one might marvel at a rare animal.”

A thoughtful reader, who may have taken pleasure in Aoyama’s lush descriptions of food — as well as her equally sensual “taste” for Chizuru — is left with a sense of complicity. There is no such thing as an apolitical travelogue or food blog,Yang suggests. You must acknowledge your entanglement in social relations before engaging with another culture. No one can stand apart or above — neither from the country they visit nor the one they call home.

What ultimately dooms their relationship is not power disparity but rather another social force: heterosexual marriage.

Myriad questions, at root political, abound in the book. Is a colonizer’s delight in local food innocuous, praiseworthy, nefarious, or all of the above? Can two women from such different class backgrounds, one from the empire and the other the colony, become true friends (or even lovers, though that word is never used)? Aoyama thinks yes, and Chizuru seems to think no.

Where does the author fall? Based on the novel’s afterwords, I’d wager that between the two, Yang Shuang-zi lies closer to Aoyama’s romantic idealism. As such, the palimpsest of perspectives in the book’s narration is fascinating. Yang is Taiwanese, writing in the voice of a Japanese woman in love with an inscrutable Taiwanese woman. What ultimately dooms their relationship is not power disparity but rather another social force: heterosexual marriage. A web of relations pushes women towards it, foreclosing an independent life. “For women,” Chizuru tells Aoyama, “marriage is always a division between her past life and the rest of her life.”

If it’s not clear by now, men are barely depicted in this book. This is one of Yang’s three yuri books, a Japanese genre of same-sex friendship and love between girls. (Though yuri is not erotic literature, desire sometimes ends up playing a part.) The yuri genre is often discussed in relation to its male equivalent “boy’s love” or BL, but it’s worth noting how, in Taiwan Travelogue, yuri writing enriches and subverts a different genre: that of unreliable narrators.

In books such as Lolita, Remains of the Day or Open City, the unreliable narrator is male and profoundly self-avoidant, whose prevarications entangle women in doomed relationships. Here, “unreliable” often means repressed, self-rationalizing, compartmentalized, inarticulate about matters of the soul, and ultimately unfixable. But as any woman with a truly close female friend knows, self-interrogation sustains intimacy — and self-knowledge is its fruit. As Taiwan Travelogue unfolds, it becomes clear that Aoyama’s blind spot is indeed her colonial arrogance. Still, Aoyama’s fear of losing Chizuru propels her to change. Desiring continued intimacy, she’s willing to admit fault. In Yang’s hands, one genre resolves another.

Yang Shuang-zi herself — unlike the elusive Chizuru — has been explicit about Taiwan’s colonial situation, not mincing words in describing her country’s precarious global position. “For the past century, one constant has been our proximity to a powerful and aggressive neighbor,” she said in her National Book Award acceptance speech — words that were widely circulated across social media in Taiwan, where I live. She stated:

A hundred years ago, Taiwanese people already said, “Taiwan is the Taiwan of the Taiwanese.” A hundred years later, today’s Taiwanese people still say the same thing, but the people to whom we’re speaking has changed. A hundred years ago, we said it to the Japanese; today, we say it to the Chinese.

In the speech, Yang continued, “I write to answer the question: Who are the Taiwanese? And I continue to write about the past to move towards a better future.”

Who are the Taiwanese in this novel? They are people who were not taught to feel proud of their humble origins. At the very end of the novel, Aoyama, playing detective, guesses aloud the circumstances of Chizuru’s mysterious origins. In reply, Chizuru speaks for the first time about how she was raised:

This is the first time openly admitting to my roots, and I will never do so again to anybody else. Yet despite this, Aoyama-san and I can never become true friends—it is ultimately impossible for a Mainlander and Islander to share a friendship of equals.

One brilliant aspect of the book, which deepens its heartbreak, is the ambiguity surrounding Chizuru’s rejections of Aoyama’s advances. This ambivalence lies at the heart of the novel’s power. What accounts for it? Their difference in status? The taboo of same-sex love? The possibility of intimacy with a colonizer? Is Chizuru afraid of damaging relations with her family, who have facilitated a socially advantageous marriage? Or perhaps she glimpses that a life of being “treasured as an individual” means being held accountable to her own dreams. Nothing has prepared her to regard her own flourishing as a matter of significance. An intimate relationship where she’s treasured might very well be more taxing than an arranged heterosexual marriage — for which life has prepared her.

Taiwan Travelogue is structured like a nested egg: the story of Aoyama and Chizuru is preceded by a scholarly foreword and followed by successive afterwords. The conceit is that Aoyama’s original text, published as a novel in 1954 in Japan, is reprinted in 1970 (with an afterword), translated in 1977 (another afterword), self-published in 1990 (with yet another afterword) and re-translated in 2020 by the author Yang Shuang-zi. (The English translation also contains another afterword from Lin King.) Yang’s own afterword mixes truth and fiction, describing how, while traveling in Japan in 2014 with her late sister, she discovered the novel. While the novel is fake, the detail about the sister is true. “Shuang-zi” is Yang Jo-tzu’s pen name, meaning “twins,” adopted as an homage to Yang’s twin sister who was diagnosed with cancer and passed away in 2015. The two were fascinated with yuri culture and had made a pact to write together.

These multiple editions across the passage of time suggest that love, though unconsummated or imperfect, endures and finds new forms. Each time a new edition is released, it’s infused afresh with the longing of the people who bring it to life — writers, translators, scholars and, of course, ourselves, the readers. Each afterword advances the plot, generating revelations, questions and new pleasures. Yet as each new edition appears, the original text becomes more encircled and distant. These two young women who encounter one another in Taiwan will never see each other again. Reduced to a trace of the past, their love — and the missed opportunity that defines it — takes on greater poignancy. Ultimately, their power disparity, geopolitics, migration and social pressures separate them. As Aoyama relates not long after being rejected yet again, upon telling Chizuru to come with her to Japan:

I thought I caught a glimpse of moisture in her eyes when she said, “But I really wasn’t lying. Aoyama-san, you are the only person in the world who treasures me.”

“Then be my friend!”

“Alas, I truly cannot.” ∎

Header: A 1928 painting of Japanese soldiers entering Taipei City in 1895 after the Treaty of Shimonoseki between Qing China and Japan. (Ishikawa Toraji, public domain)

Michelle Kuo is a writer and educator. She is an editor at Books from Taiwan and teaches at the International College of Innovation at National Chengchi University (NCCU). Kuo’s book Reading with Patrick (Random House, 2017) was a runner-up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and has been recommended by Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture. She holds a B.A. and J.D. from Harvard University and co-writes Broad and Ample Road, a newsletter about Taiwan.