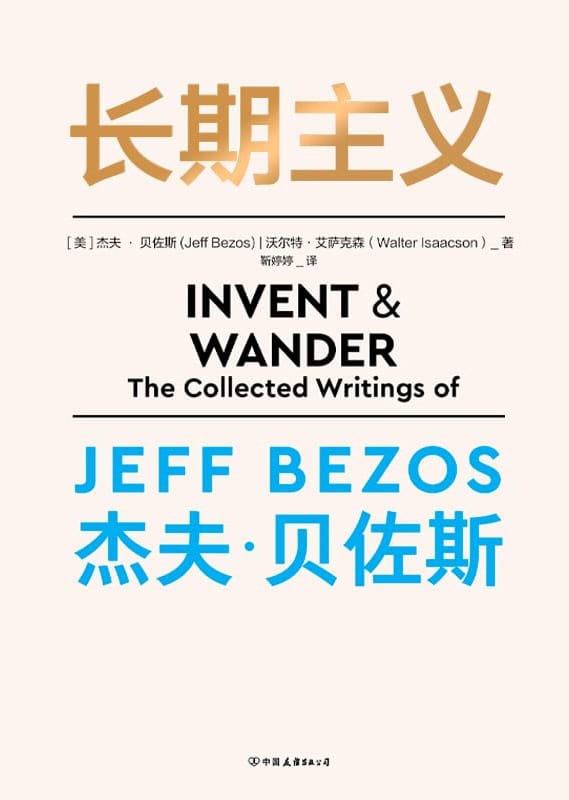

In 2020, one of China’s leading private-sector book publishers, Beijing Motie Book (磨铁图书), bought the Chinese-language rights to Invent and Wander: The Collected Writings of Jeff Bezos (Harvard Business Review Press, 2020). Motie thought the book was perfectly timed for the Chinese market. The Amazon founder was then the world’s richest man, and his Chinese technology billionaire peers were also riding high.

But it was also the final year of Donald Trump’s first term and Sino-U.S. relations were at a nadir. As a result, Motie was unable to get final clearance from the National Press and Publication Administration (NPPA), the Chinese agency that oversees print publications and sometimes steps in to halt potentially sensitive titles. “At that time, many American books could not get published,” said a former book editor at Motie, who asked not to be identified. “It was stupid. Whenever China does not get along with a country, it will ban its books or it will delay them for a long time.”

Invent and Wander, titled Longterm-ism (长期主义) in Chinese, was eventually published in 2022, but it had missed its moment. By then President Xi Jinping had launched his campaign to rein in Jack Ma and other influential technology moguls, and prominent Chinese entrepreneurs pulled their blurbs for the book. Then, weeks before publication, Amazon announced it was shutting down Kindle’s business in China. The book sold a fraction of the 500,000 copies Motie had expected. “A lot of this is beyond the control of an editor or a publisher,” adds the editor. “But it really wears you down.”

Industry insiders like to say that to publish books in China is to “dance in chains.” Ever since the Chinese Communist Party came to power, publishers have been shackled by various degrees of state control. The goal is to find a way through the system and produce books people want to read. For others, the chains are not metaphorical but all too real. Under Xi, there have been well-documented instances of police hunting down Chinese publishers based in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand, either nabbing them on their trips back to China or renditioning them from abroad.

Today the industry faces a dual predicament, according to Zhang Shizhi, a former executive at a major state-owned publisher in Sichuan. It is, he said, both “encircled” by an ever-tightening censorship regime on the political front, while on the commercial front publishers are being “chased” to the bottom by intense competition and financial pressures. “Everybody is embroiled in a price war,” he said. “Publishers are wailing — it is very difficult. If this situation does not change, there will be no books worth reading in China in five to ten years.”

Industry insiders like to say that to publish books in China is to ‘dance in chains.’

Books were once so rare in China that many literary figures tell stories about how they hungered and hunted for reading materials. Mo Yan, the Nobel prize-winning writer, milled grain for his neighbors for the chance to flip through the one novel they owned. Yu Hua, another celebrated Chinese novelist, received tattered paperbacks that had passed through so many hands they were missing pages. He filled in the gaps with his imagination.

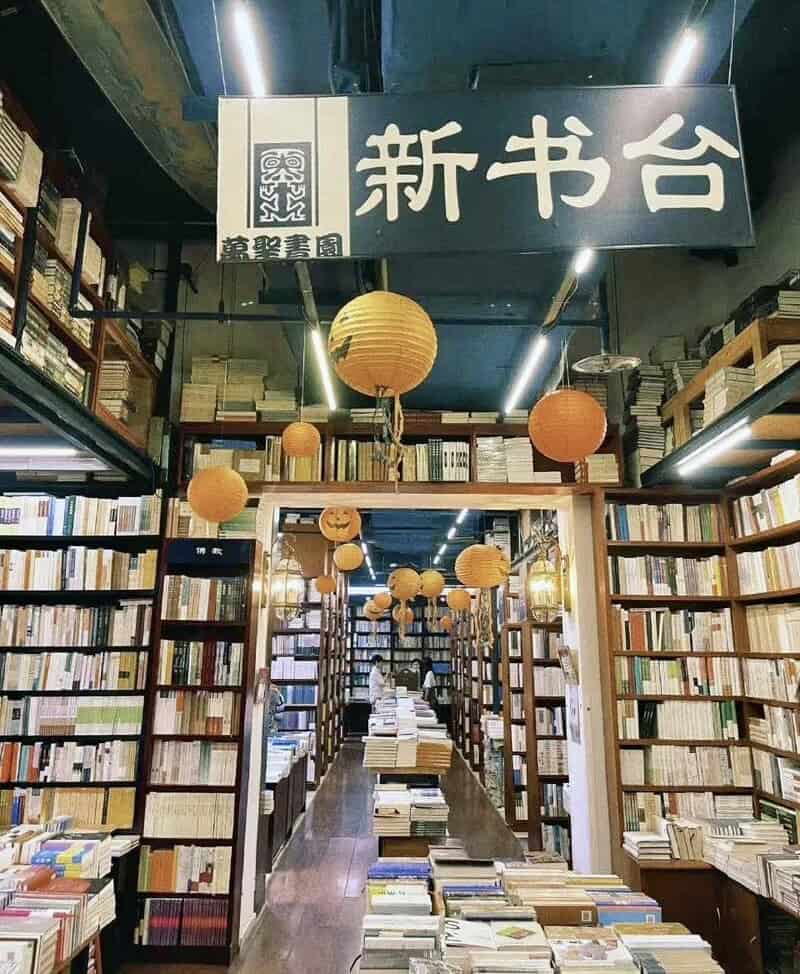

As Liu Suli, a well known bookseller, told Caixin, “We were a generation starving for books.” In the 1980s and 1990s people bought books as if they were “gold,” he added. After serving a brief prison sentence for his role in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, Liu established All Sages Bookstore in Beijing in 1993. It is one of few independent bookstores that remains open as the Chinese government tightens its chokehold on cultural spaces.

It is not the Communist Party’s stated intention to crush the publishing industry. The annual government work report delivered by Chinese Premier Li Qiang in March emphasised the importance of “fostering a love of reading among the public” — provided that the people’s love of reading does not extend to books party cadres don’t like. The NPPA also promised to regulate book prices, which have fallen precipitously over recent years, in the five-year plan unveiled by the government in 2022. But interviews with more than a dozen publishers, editors and writers reveal how difficult political and market conditions have upended the publishing industry and rewritten the rules of the game.

Commercially, the tipping point came during the pandemic. Affected by widespread and often lengthy lockdowns, Chinese readers could not go to bookshops, book fairs or libraries. The three-year freeze accelerated the trend towards online sales and led to a collapse in booksellers’ margins. But even with the pandemic now in the past, industry executives fear that China’s youth, fixated on other forms of entertainment, will not value books the way previous generations had.

Industry revenues fell 10% to 111 billion yuan ($15 billion) last year, compared to the previous year, according to Centrin Ecloud, which collects data on the industry. Excluding textbooks, the year-on-year decline was 17%. Publishers’ real revenues are also likely to be significantly less as these figures are based on list prices, and therefore do not capture widespread and deep discounting.

The rapid rise of e-commerce and social media platforms that have replaced bookstores as the main channels for distribution, accounting for up to 80% of sales, has been particularly damaging. Platforms such as JD.com have put pressure on publishers to slash prices amid the economic downturn. In the U.S. the paperback edition of My Lost Daughter, a novel by Italian writer Elena Ferrante that was highly rated in the category of foreign literature on the Chinese book review site Douban, is priced at $16 at Barnes and Noble and $8.99 on Amazon. On several Chinese sites, its translation sells for 22.5 yuan ($3).

In May last year, dozens of publishers decided to take a stand. They refused to take part in JD.com’s annual shopping festival because mandatory steep discounts would have forced them to sell at a loss. In contrast to the U.S., where major publishing companies still have some bargaining power with Amazon, Chinese publishers have not been able to bring online platforms to the negotiating table. “If they don’t comply with the price cuts, the platforms would just drop their books,” said Li Xingxing, an analyst at a Beijing-based publishing consultancy. For some publishers, that could jeopardize more than a fifth of their sales. “No one can afford such a loss in the current environment.”

Chinese publishers’ post-Covid dependency on online platforms has led to an additional, margin-crushing reliance on livestream hosts and influencers on social media apps such as Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, and Xiaohongshu. These online video platforms are the only distribution channels for books that enjoyed an increase in sales last year, growing by 24% compared to 2023.

Thanks to their huge followings, top livestreamers can make or break a book, or even give new life to an old title. The Last Quarter of the Moon, an award-winning Chinese novel first published in 2005, shot up the charts and sold 5 million copies in 2023 after Dong Yuhui, a teacher-turned-influencer, recommended it to his nearly 29 million followers on Douyin. The book’s accumulated sales jumped nearly tenfold.

In return, popular figures on social media demand as much as 500,000 yuan ($68,000) for a spot in their livestreams. They take a cut of the sales as well. Chinese authors typically receive royalties of 7% to 12%, similar to their American and European peers. Chinese influencers, by comparison, can command up to 30% of the sales. To draw traffic, some hold firesales for the books they agree to promote, further eroding industry profits.

Huang Yuhai, founder of publishing house Shanghai 99 Readers, broke down the math in a recent interview with the magazine T China. For a book priced at 100 yuan, he said, royalty, printing and translation fees alone account for 25 percent of its cost. “So when a livestream host is selling my books for 25 yuan, how is a publisher supposed to live?” he lamented.

There are still bright spots amid the gloom, and books that attract readers speak volumes about undercurrents in society. “One of the bestsellers over the past six months has been Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own,” said Alicia Liu at Singing Grass, a UK-based consultancy that has advised several international publishing companies on the Chinese market. She attributes the popularity of Woolf’s 1929 classic to a “real feminist revival in China,” especially among Gen Z women readers.

Another popular genre is books that center on the real-life experiences of ordinary people, such as I Deliver Parcels in Beijing or My Mother is a Cleaner. The Chinese translation of journalist George Packer’s The Unwinding, about the economic decline of the American heartland, became an unexpected hit in 2022 because it dovetailed with the Xi administration’s narrative that the U.S. is a failing nation.

In this environment, both the quality and diversity of books suffer. It is reflected in the selection of books available at bookstores and this in turn affects people’s desire to read. It’s a vicious cycle.

Yu Miao

But in today’s difficult political and commercial climate, fewer and fewer publishers are willing to invest time or money to develop and commission original works that are of value. “There’s a strange phenomenon, where everyone is reading literary works from two to three decades ago,” said Stanley Chen Qiufan, a well-known Chinese science fiction author. “There are hardly any new writers or new titles gaining traction.”

Instead of selecting books based on quality, now it’s all about how many copies publishers can sell, said a director under a state-owned printer, who asked not to be named because she is not authorized to speak to the media. Companies are going after works by influencers or celebrities whose massive followings can guarantee sales, as well as self-help and guide books that have the potential to go viral. “The industry used to have standards and principles, but they have been destroyed in the last decade,” the director adds. “Books are basically fast-moving consumer goods now.”

Latest hits in the market reflect the pivot. Manuals for the Chinese AI model DeepSeek and Chairman Mao’s selected works dominated nonfiction bestseller charts in March, according to OpenBook, a Chinese company that tracks industry data. A comic book adaptation of the animated blockbuster Ne Zha 2 topped the fiction chart. Others are banking on reprints of Chinese and Western literary classics — such as Dream of the Red Chamber and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude — especially if their copyrights have expired.

“In this environment, both the quality and diversity of books suffer. It is reflected in the selection of books available at bookstores and this in turn affects people’s desire to read,” said Yu Miao, former owner of Jifeng Books, a famous independent Shanghai bookstore that was forced to shut in 2018. “It’s a vicious cycle.”

China’s first wave of private booksellers emerged in the 1990s, breaking the longstanding monopoly of state-owned Xinhua Bookstore. Pent-up demand from earlier decades of repression exploded. By 2003, they had seized more than half of the retail book market. A decade later, however, Xi Jingping began his remarkable rise to a position of power unprecedented since Mao. His administration restored discipline to a censorship regime that was more relaxed under his predecessors.

These days many private publishers are heavily in debt and “lying flat,” said a publishing executive who declined to be named because she is not authorized to speak to the media. “I haven’t met any companies that aren’t laying off staff,” she added.

By contrast, and as in so many other industries in Xi’s China, state-owned publishers are insulated from many of the pressures grinding down their private sector competitors; they have lifelines they can reach for.

Their first great advantage is their monopoly over International Standard Book Numbers, the 13-digit codes used to identify and catalog books and better known as shuhao in China. Only state-owned publishers are allowed to issue shuhao, which they sell to private-sector rivals. Although the practice was never formally recognized by law, it effectively means many reap profits while sitting on their hands. A reduction in the number of shuhao allocated to each state-owned publisher since 2018 has also driven up the average prices of shuhao. While they used to cost around 10,000 yuan ($1,370) to 20,000 yuan ($2,750) in the early 2010s, now they fetch as much as 60,000 yuan ($8,250).

They have other easy sources of income as well. One is textbooks, which accounted for one quarter of the overall book market last year, according to data from OpenBook. Some have looked beyond their core business, branching out into real estate or parking their cash in wealth management and investment products.

Everybody is almost by definition extremely conservative in their approach because they know that if the spotlight is put on them or a particular title, the repercussions can be serious.

Peter Goff

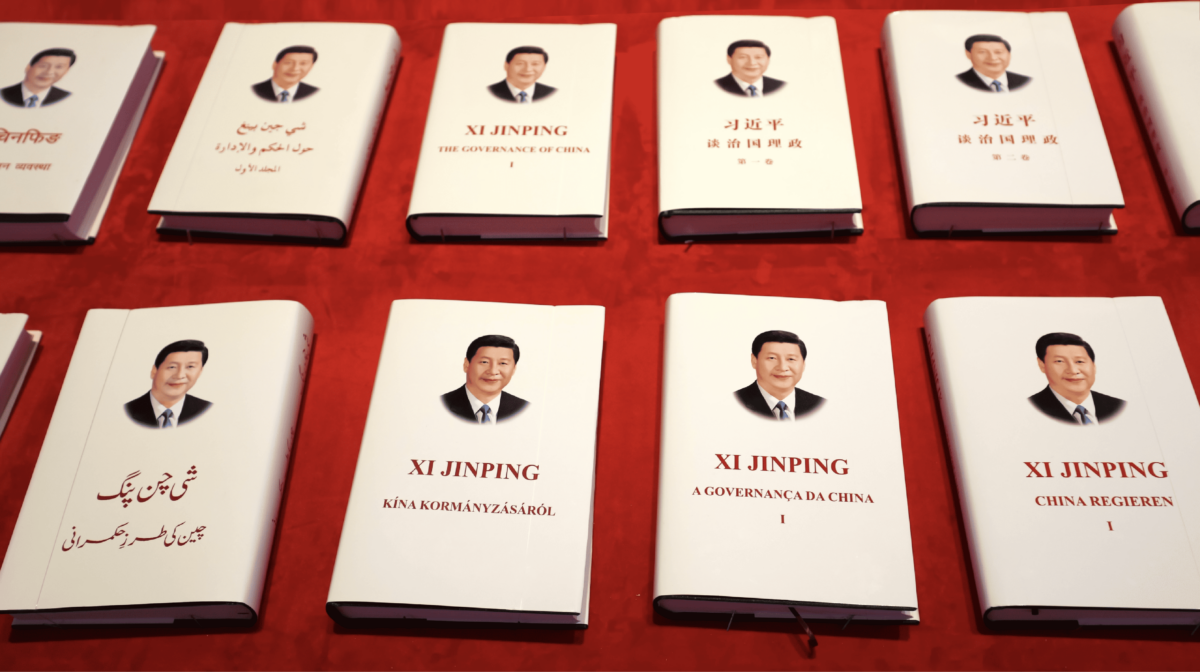

Some of these sources of revenue are looking less certain in China’s cool post-Covid economic climate. Even putting out books on themes promoted by the government each year, such as tracts on Xi Jinping’s political thoughts and governance philosophies, isn’t as lucrative as it used to be. In the past, smaller state-owned publishers could work with local Party cells to mandate purchases, such as requiring every student at a school to buy a copy. But with local governments and households also under financial strain, these avenues are no longer as effective. “In sinking markets, publishers are racking their brains to sell themed books,” said the publishing executive.

State publishers’ political calculations have also shifted. Since its introduction, the shuhao system has effectively turned them into frontline censors. The onus is largely on them to read between the lines and screen for problematic content. They have toed the Party line over the course of Xi’s 13 years in power. But in order to play it safe, some are self-censoring even more than is really necessary.

When working for his former state-publisher in Sichuan, Zhang’s superior once rejected a memoir in which the writer harkened back to his childhood in China’s industrial northeast rust belt, because of its gloomy tone. The content may not have been critical of Xi or the Party, but it did not align with the tune they are singing about prosperity. “It has become a situation where if you aren’t praising or extolling the country, the [publishing] process will be troublesome,” Zhang said.

“The whole system is based on strategic ambiguity,” said Peter Goff, co-founder of the Bookworm bookshop, which operated outlets in Beijing, Chengdu and Suzhou for over a decade until they closed in 2019. “There’s no clear definition of what’s okay and what’s not okay. Everybody is almost by definition extremely conservative in their approach because they know that if the spotlight is put on them or a particular title, the repercussions can be serious.”

“There are opportunities for real discourse still,” he adds. “But it is limited and it is a tap that can be turned off at any point.”

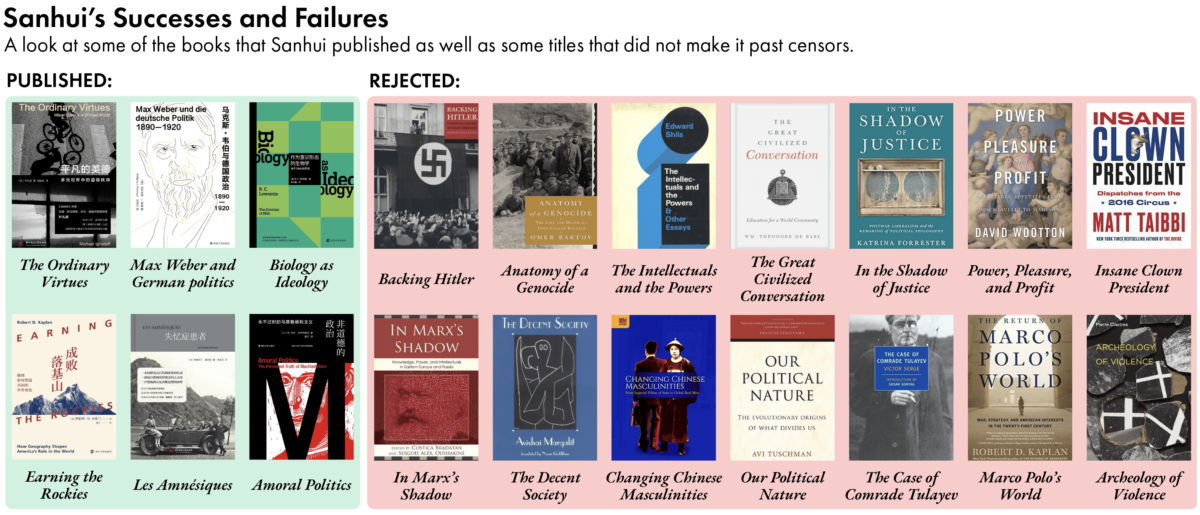

For Shanghai Sanhui Culture and Press, a private publisher, the tap had slowed to a trickle. For two decades, its founder, Yan Bofei, a former scholar at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, was known for selecting weighty titles. They included The Origins of Totalitarianism by philosopher Hannah Arendt and They Thought They Were Free, Milton Mayer’s examination of the rise of fascism in pre-World War II Germany. In 2011, it published Reading Lolita in Tehran, a memoir by Iranian author Azar Nafisi, after lobbying different state-owned publishers to take on the project.

But Sanhui had fewer and fewer successes like that in recent years. In 2022, only six out of 26 books teased by the company were ultimately released. Meanwhile, the list of rejected titles grew so long that the company started a new column on WeChat featuring their excerpts. Among them were Backing Hitler, an examination of how the Nazis cultivated popular support by Canadian scholar Robert Gellately, and The Decent Society by Israeli philosopher Avishai Margalit.

Most failed to launch because no state publisher would issue Sanhui a shuhao. While there used to be room for negotiation with state-employed editors willing to push boundaries, Sanhui and other private-sector publishers were increasingly stonewalled. “For topics related to politics and philosophy that fall into sensitive categories, they would reject the book before they had even read the contents,” Yan said.

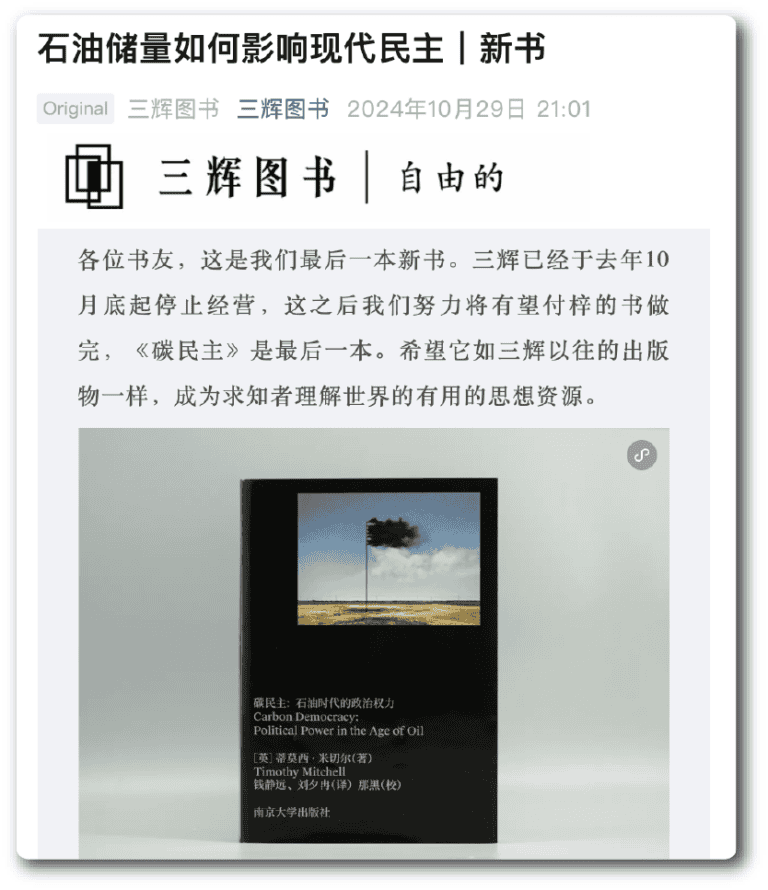

Last October, Sanhui announced that it was publishing its last book. Yan estimated that in recent years only about 10% of the books in Sanhui’s pipeline were eventually printed. “It’s impossible for a company to survive in such a situation,” he said.

Sanhui’s closure is likely to be followed by many more. Private sector publishers, especially smaller imprints, are facing an existential crisis. “The question right now is to be or not to be,” said Wu Qi, editor-in-chief of One-Way Street, a literary journal in Beijing. “They are deciding if they want to continue, if they can sustain their operations and [whether] there is any meaning and future for the industry.”

Hopeless at home, some Chinese publishers have moved to Japan, Europe and the U.S. in their search for a way ahead.

Zhang, the former state-sector publishing executive, left his high-flying career to set up the publishing house Yomimichi in Tokyo in 2023. In his previous government job, he directed the publication of books whose sales reaped tens of millions of yuan a year; these days he prints maybe 800 copies at a time and delivers them to bookstores himself. But he has found an unexpected upside: “The Chinese publishing scene has become so restrictive that some of the best writers in the world are coming to us.”

Others found that, even as far away as Washington D.C., Xi’s shadow still falls over the diaspora. Yu, who reopened JF Books in Dupont Circle last fall, said many Chinese people have internalized their fears back home and carry them wherever they go. Some readers attend book talks at his store with their faces covered; others check if certain books can be brought back to China before buying them. “They have set all these red lines for themselves.”

But for Yu, it doesn’t really matter how many books he sells in exile or what impact they have. “I know this is the right direction,” he said. “That alone gives it meaning.” ∎

This article first appeared in our sibling site The Wire China, under the title “A Vicious Cycle.”

Rachel Cheung is a staff writer for The Wire China based in Hong Kong. She previously worked at VICE World News and South China Morning Post, where she won a SOPA Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture Reporting. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Columbia Journalism Review and The Atlantic, among other outlets.