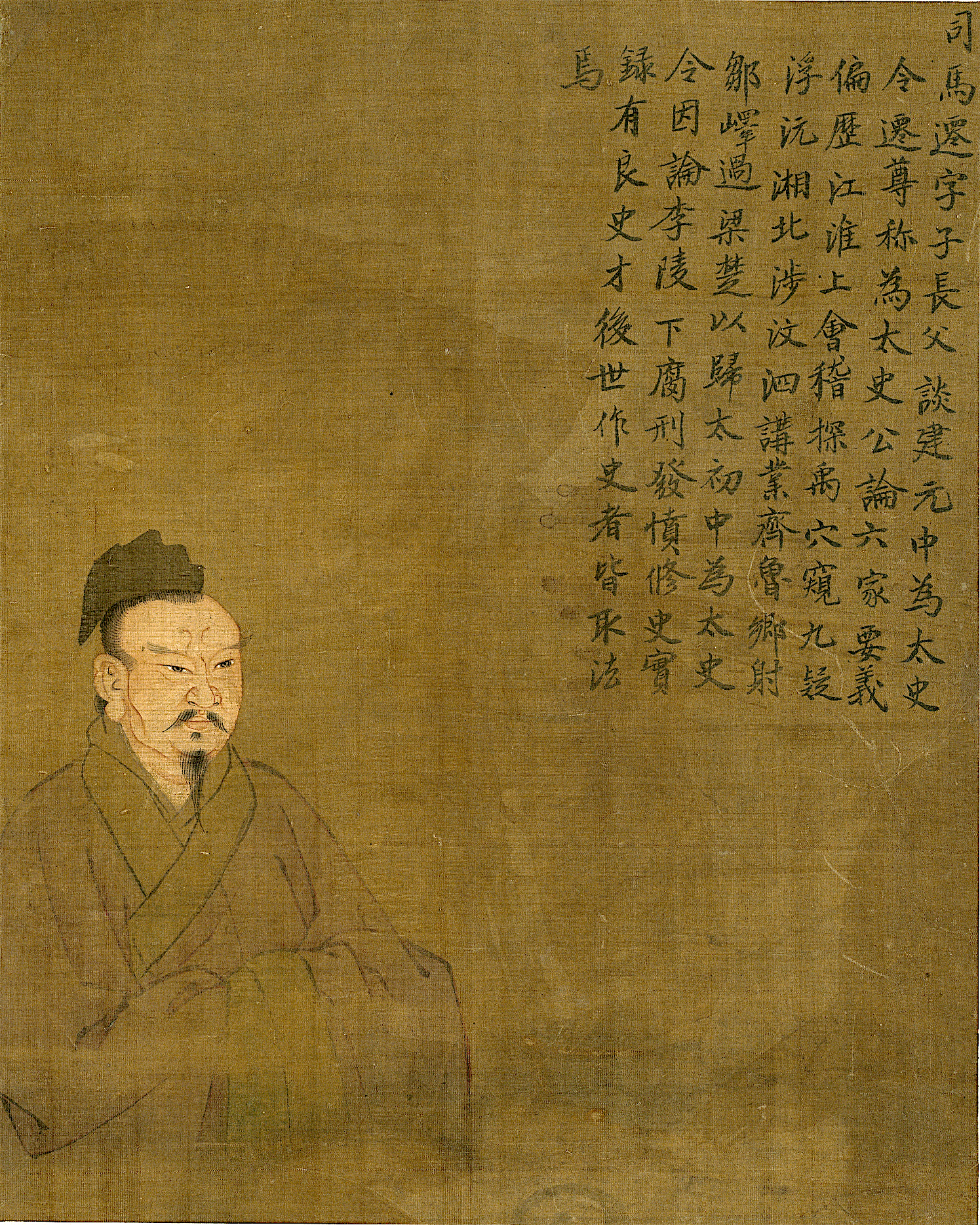

The year is 99 bce. Sima Qian (司马迁) is an official record-keeper in the court of the Emperor Han Wudi, one of the most famous rulers of the Han Dynasty. The emperor is furious that General Li Ling, a friend of Sima Qian, has defected to the Xiongnu, the horseback-riding nomadic enemies of the Han. Unable to punish the absent commander, the emperor proposes executing the general’s family members instead.

Sima Qian speaks out in defense of his friend, so the emperor’s ire turns toward him. Han Wudi orders Sima Qian to be executed for having the temerity to criticize the throne, but Sima Qian begs to be castrated instead as a way of commuting his death sentence. Sima Qian wrote to a friend, Ren An, about his dilemma:

A man has only one death. That death may be as weighty as Mount Tai, or it may be as light as a goose feather. It all depends upon the way he uses it. … I grieve that I have things in my heart that I have not been able to express fully, and I am ashamed to think that after I am gone, my writings will not be known to posterity.

At the time, Sima Qian was still years away from completing his masterpiece, an epic history of China covering 2,500 years from the time of the mythical Yellow Emperor to his own era, the Shiji (史记) or Records of the Grand Historian. And so the man who would one day be considered China’s greatest historian suffered unspeakable pain, mutilation and disgrace in order to finish his assignment.

Sima Qian was born to do this job. His father, Sima Tan, held a similar position at court, and had laid the groundwork for what became the Shiji. For Sima Qian, finishing the Shiji was as much about his father’s legacy as his own. He completed it in 91 bce, though at first it only circulated among court scholars and elites. Gradually the Shiji became essential reading for officials who needed to understand precedent, statecraft and the moral lessons of dynastic rise and fall.

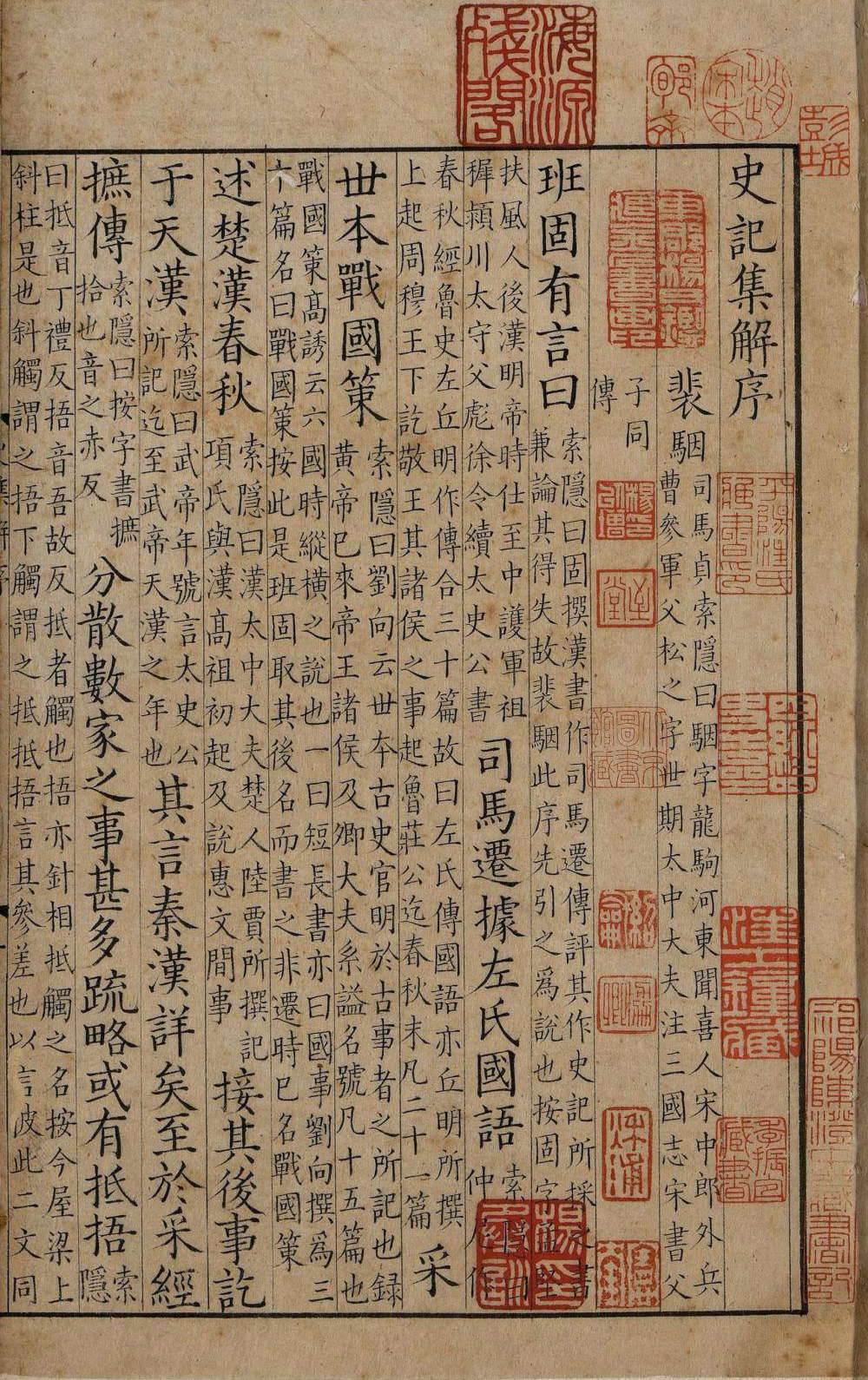

The Shiji is more than a book: it is an immense compendium, 525,000 characters long, with 130 juan (chapters) divided into sections that include chronologies, treatises and famous texts, genealogies and biographies. Making allowances for the terseness of classical Chinese writing, the Shiji contains roughly the same amount of information as Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War and the Old Testament combined.

People often call Sima Qian the “Chinese Herodotus” — which is a bit like calling the director Zhang Yimou the “Chinese Spielberg.” It’s not entirely inaccurate, but it misses the point. Herodotus wrote history as ethnography and moral inquiry. Thucydides wrote it as political realism. Sima Qian wrote it as statecraft — even soulcraft — and imbued his narratives with the same deep sense of right and wrong that got him in trouble with the emperor. Rulers rise and fall, human virtue flickers and fails, and amidst it all, Sima Qian is there keeping score. He wrote a history of his world down to the time he lived, and in so doing crafted the urtext for Chinese historiography.

Sima Qian imbued his narratives with the same deep sense of right and wrong that got him in trouble with the emperor.

Sima Qian was a historian’s historian: a tireless collector of sources, traveling throughout the empire, digging through local archives, sitting in libraries, sifting through imperial annals, recording oral histories, legends and myths. As he gathered his material, he carefully evaluated historical evidence and compared sources against each other:

I myself have travelled west as far as K’ung-t’ung, north past Cho-lu, east to the sea, and in the south I have sailed the Yellow and Huai Rivers. The elders and old men of these various lands frequently pointed out to me the places where the Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun had lived, and in these places the manners and customs seemed quite different. In general those of their accounts which do not differ from the ancient texts seem to be near to the truth.

Why should a modern reader choose to dive into such deep waters? Because like all great historians, Sima Qian balances his rigorous methodology with a storyteller’s love of narrative and character. The Shiji is full of richly drawn heroes and villains, with as much intrigue and as many plot twists as the last season of Love Island. These biographies are divided into sub-categories that Burton Watson, translator of the most famous English-language version of the Shiji, renders with colorful titles such as “Wandering Knights,” “Harsh Officials” and “The Emperor’s Male Favorites,” featuring colorful historical vignettes:

Emperor Kao-tsu [Han Gaozu, founder of the Han Dynasty], for all his coarseness and blunt manners, was won by the charms of a young boy named Chi. Chi … [didn’t have] any particular talent or ability; [but] won prominence simply by their looks and graces. … As a result all the palace attendants at the court of Emperor Hui took to wearing caps with gaudy feathers and sashes of scarlet; and to painting their faces, transforming themselves into a veritable host of Chis.

Like his Greco-Roman counterparts, Sima Qian is not afraid to spice up a story with some creative interpretation of the sources, or to take creative liberties by inventing dialogue. As any HBO executive will tell you, if you want to sell a story, add dragons, damsels and sex. Or even better, damsels having sex with dragons:

The mother of Kao-tsu was one day resting on the bank of a large pond when she dreamed that she encountered a god. At this time the sky grew dark and was filled with thunder and lightning. When Kao-tsu’s father went to look for her, he saw a scaly dragon over the place where she was lying. After this she became pregnant and gave birth to Kao-tsu.

Sima Qian’s story-telling also helped to coin various Chinese sayings that are now commonly used. “Calling a deer a horse” (指鹿为马, the deliberate peddling of falsehoods) derives from a treasonous official who gifted a deer to the emperor but called it a horse, as a test to see which other officials would join him in the lie. “To break cauldrons and sink boats” (破釜沉舟, crossing the Rubicon) comes from the warlord Xiang Yu, who destroyed his army’s cooking pots and boats after crossing a river, forcing them to fight with no possibility of retreat. And “to sleep on brushwood and taste gall” (卧薪尝胆, enduring hardship to achieve a goal) originates from the story of King Goujian, who endured years of humiliation as a captive, then slept on rough brushwood and drank bitter gall daily to remind himself of his shame, until he returned to defeat his captors.

It’s not all just fun with stories and clichés. The Shiji is a foundational text for understanding Chinese history and politics. Other writers, notably Mencius, had previously expounded on the Mandate of Heaven (the idea of a divine right to rule that could be lost as a result of misbehavior) but the Shiji abounds with examples of corrupt, venal or stupid rulers getting their cosmic comeuppance. Take King Zhou, the last king of the Shang Dynasty, which fell in 1046 bce. According to Sima Qian, King Zhou was a debauched nightmare and his dynasty collapsed as a result:

He prided himself on surpassing his ministers in ability and considered himself superior to all under Heaven, believing that everyone was beneath him. He loved wine and debauchery, and was infatuated with women. He increased taxes to fill the treasury with money and to overflow the granaries with grain. He was disrespectful toward spirits and gods. He held great entertainments, making pools of wine and hanging forests of meat, having naked men and women chase each other among them, drinking through the long nights.

Most importantly for modern readers, the Shiji is a literary achievement. Sima Qian writes beautiful classical Chinese in a style that has challenged translators for centuries. The stories are lively, didactic and entertaining. Nevertheless, reading the Shiji in its entirety is probably not feasible for most readers, especially as the complete text has yet to be translated into English. Burton Watson’s translation, first published in 1961, cherry-picks the chapters and takes liberties with fidelity to its source in the service of telling a good story. It was re-released in 1993 in a revised edition with three volumes, which might not seem like an abridgment, but they only cover about 90 of the 130 original chapters. There is also an unfinished nine-volume translation by William Nienhauser that emphasizes fidelity to Sima Qian’s original text over readability or accessibility, with copious footnotes and thoroughness.

Why should we continue to read the Shiji today? Because in an era when telling stories of the past requires both skill and courage, Sima Qian remains an icon of both. He spoke truth to power and paid a terrible price. He need not have worried about whether his impact on this world would be light as a feather or as heavy as a mountain. The Shiji continues to be read and matter, its words long outliving those who tried to silence the man who wrote them. The moral lessons of the Shiji remain deeply encoded in the DNA of Chinese culture, and many Chinese quote passages from it like they are reciting scripture. In an age of algorithmic amnesia and curated half-truths, The Records of the Grand Historian is a reminder that facts have legacies, and that historical writing when done with conviction can be a form of immortality, no matter the cost. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.