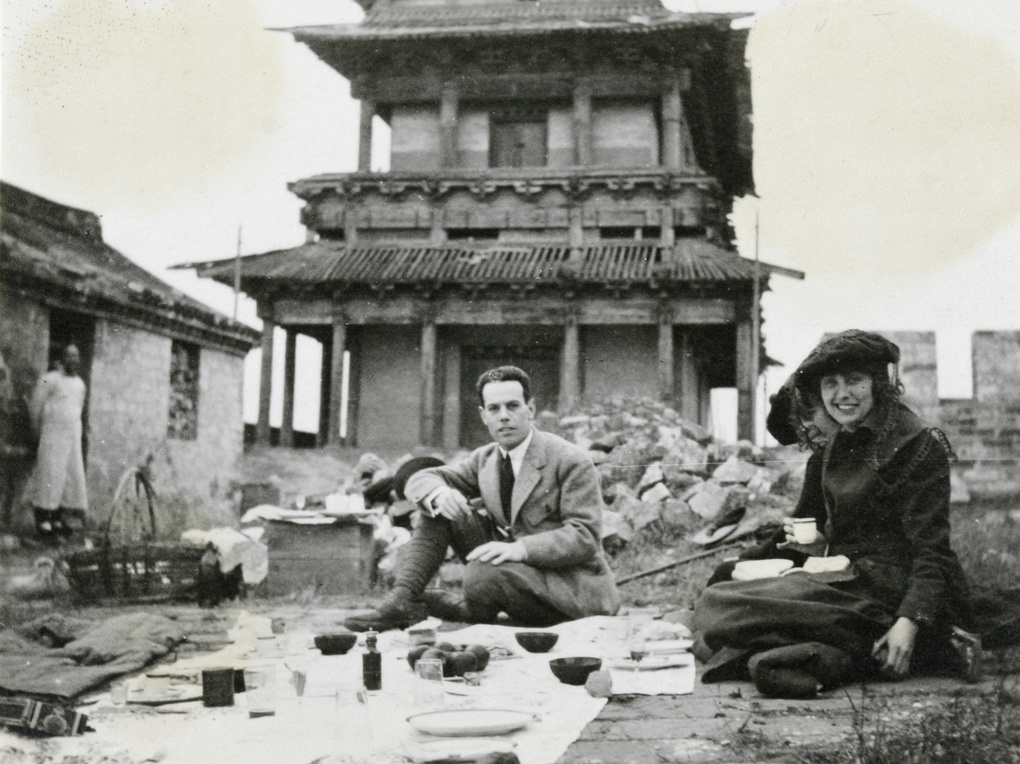

Ann Bridge’s 1932 literary debut, Peking Picnic, follows a group of mostly British and American foreigners over the course of a three-day eponymous “picnic” to Jietai Temple in the Western Hills of Beijing. At first glance, the book is a novel of manners, given an exotic twist by being set on the outskirts of Beijing rather than a drawing room in the heart of Mayfair. After all, nothing says “manners” like a party of expatriates invading a Buddhist shrine for a weekend of cocktails, romantic intrigue and smoking. Lots and lots of smoking.

The novel’s protagonist, Laura Leroy, is the center of gravity for an orbiting cluster of diplomats, along with their friends and visiting relatives. Laura displays near-mystical levels of courage and calm, whether helping the group navigate the tender mercies of youthful romance or guiding her fellow picnickers through moments of genuine peril. Another character gushes over her “extraordinary virtuosity in your touch on life.” Unlike most of her weekend companions, Laura is proficient in Chinese and navigates Chinese culture with the skill, wisdom and panache of a Confucian scholar, despite having been in the country for only a few years. But beneath her Mary Sue exterior, Laura carries not just her suitcases but a fair weight of emotional baggage. As the novel progresses, the author steadily strips away Laura’s stoic veneer, revealing a more interesting and morally complex figure.

There are many points of overlap between Laura and the author. Ann Bridge was the literary pseudonym of Mary Ann Dolling Sanders (1889-1974) or “Lady O’Malley,” who lived in Beijing from 1925 to 1927 as the (reportedly unhappy) wife of British diplomat Owen St. Clair O’Malley (1887-1974). While Peking Picnic isn’t set in a specific year, the use of the city name Peking (in 1927 it changed to Beiping, then in 1949 to Beijing), and the backdrop of warlord armies vying for control of the city, suggest the story takes place during the time when the O’Malley’s were stationed in China.

Lady O’Malley was no doubt acquainted with life in the Legation Quarter, the walled two-square-kilometer enclave in the heart of Beijing that isolated 2000 or so foreign inhabitants from the millions of Chinese residents who surrounded them. Her experiences within this cloistered community provided ample material not only for Peking Picnic but also inspired two other novels set in China, The Ginger Griffin (1934) and Four-Part Setting (1938), although none matched the success of her first book. Upon its publication, Peking Picnic was a sensation and earned a $10,000 prize (equivalent to $225,000 today) from the publishers of Atlantic Monthly.

Nothing says “manners” like a party of expatriates invading a Buddhist shrine for a weekend of cocktails, romantic intrigue and smoking.

A central theme of the book is the feeling of displacement all too common to expats. Bridge ably captures the psychology of the sojourner who expends a great effort to become part of their new culture, yet cannot or will not wholly cut loose from their old one. Characters grapple with this dislocation that results in having to stretch a sense of self between two different places. Bridge’s protagonist Laura Leroy seems all-too-aware of this psychic toll, whereas other foreign authors in China such as Reginald Johnston became caught up in delusions of grandeur and access. These are the twin poles around which the psyches of many expats orbit, even today.

Laura feels the pull of home despite her surface savoir-faire. Perhaps, as with sojourners who dive into the deeper end of another culture, she experiences a more profound sense of bifurcation. The easier a person overcomes culture shock abroad, the greater their difficulty often becomes managing “reverse culture shock” on returning home. Over time, a more fully assimilated expat can wonder if it is ever truly possible to go “home,” or what that word might mean anymore. As the narrator writes of Laura:

She would be suffocated again by England’s smallness and muffling greenness, maddened by its petty irrational humps and hollows, after the masterly geometrical flatness of the China plain; oppressed by its grey dripping skies, after that high light firmament in which the sun glitters like a burnished shield from dawn till evening for nine months of the year.

Later in the novel, the question is posed explicitly:

Will you tell me, you philosophers, where in those moments was Laura Leroy? In her long relaxed body, resting on the sunbaked rocks above the Hun-ho? Or in the rooms and gardens of that manor house in Oxfordshire, where her spirit followed after and watched her children? If you tell me that she was certainly in China, then you make the seat of reality the body – would you wish to say that?

Adding a bit of mystery to the novel, Laura’s ties to Oxfordshire are complicated in ways only gradually brought to light in conversations and reminisces sprinkled throughout the book. She exists in a liminal fugue state, her connections to home steadily fading into a gloaming of memory and nostalgia. Yet Laura acknowledges that homesickness is a price she must pay for her new and exhilarating environment. Despite the challenges of being far from her children and England, there are magical moments when her experiences validate the traveler’s journey. For example, an early glimpse of the Forbidden City, former home of the emperors, a short distance from the Legation Quarter:

She remembered her first sight of it, on the evening of their arrival in Peking … They went through the West Gate of the Legation, across the glacis outside the Quarter, and found themselves presently in a red-walled avenue a hundred yards wide, stretching down on their left to the immense green-tiled gate-tower of the Ch’ien-mên, stretching up on their right to the red and golden Noah’s Arks, with gleams of white marble at their base. ‘There!’ said Henry. They looked. ‘It’s the eighth Wonder of the World,’ he said. And she had gone back to the house with him, partly reconciled to a place of exile which held such breathtaking beauty.

While the book features weighty themes and tense moments, Peking Picnic can still be read as a comedic novel. The characters engage in witty repartee, make snide and cutting remarks, exchange knowing glances, gossip about the (mis)behavior of others, and toss around sufficient poetic and literary allusions to warrant having the 1922 edition of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Verse on stand-by. Bridge also invites to the party that genre staple, the stereotypical Frenchman, a horndog turned on even when visiting a Buddhist temple:

They should not make Mme Kwan-yin [Guanyin] without boosums,’ pursued Henri meditatively, ‘they are most attractive in the figure.’

The novel also includes a fun bit of Anglo-American tension. Lady O’Malley was herself Anglo-American; her mother was from the state of Louisiana. While Laura’s background is not explicitly described in the book, in a letter to her daughter Laura refers to her own parents as “Grandmamma” and “Grandpère,” suggesting she may share some of her creator’s Louisiana Cajun roots. Several of the picnickers are American, notably Miss Hande, a novelist and writer of some fame, who spends time sparring with Laura on the different roles and expectations that the United States and Great Britain play in China.

Laura’s husband is, like the author’s, a diplomat stationed in Beijing. Their children, eight-year-old Tim and teenage Sarah, are at boarding schools in England. Laura’s only other family in Beijing are two visiting nieces who are catalysts for various subplots in the novel. The household also includes Chinese staff, who mainly exist as comic foils or targets of exasperation on the part of the foreign characters. Finally there is Hubbard, Laura’s maid, who is “socially dynamic,” to use a polite euphemism, among the legation’s foreign soldiers.

The easier a person overcomes culture shock abroad, the greater their difficulty becomes managing “reverse culture shock” after returning home.

Ann Bridge is a witty enough writer, and the book abounds with the sort of interwar “upstairs, downstairs” vibes that made the TV show Downton Abbey a guilty pleasure on both sides of the Atlantic. But Peking Picnic earns its spot in the China Archive for its evocative portrayal of interwar Beijing, its intimate and unfiltered immersion into the hothouse of the Legation Quarter, and the author’s poignant observations about adapting to life in China, many of which ring true today.

Current and former residents of Beijing will recognize some of the place names in Bridge’s novel, including the Legation Quarter, Hôtel de Pékin (北京饭店), the city gates Hatamen (崇文门), P’ing Tze Mên (阜成门), Shun-chi-mên (宣武门), Chang’an Boulevard (长安街) and the Qianmen Railway Station. Even the two temples, Chieh T’ai Ssu (戒台寺) and Tan-Chuëh Ssu (潭柘寺), which figure prominently in the book, remain much as they are described in the novel, although the approach to Jietai Temple is now paved.

The book is not without problems. It lacks fully realized Chinese characters, and descriptions of locals, even when attempting a sympathetic portrayal, often reflect the racism and colonial attitudes of the era. At the same time, Bridge makes an effort to subvert some of the classism and sexism that render other drawing-room stories from the same period nearly unreadable today. Throughout the story, whether in times of crisis or at cocktail hour(s), the characters also divulge aspects of themselves or their lives in ways that overturn our assumptions when we first meet the group drinking at a Legation Quarter garden party. These reveals are part of the book’s charm, and a plot twist at the end recalls contemporaneous events described in James Zimmerman’s non-fiction book The Peking Express (2023).

Contemporary readers will enjoy the colorful way the author brings to life this time capsule of Beijing’s Legation Quarter in the 1920s. The portrayal of expat angst and lyrical descriptions of Beijing and its environs make Peking Picnic a welcome travel companion for modern-day visitors to China, as well as for literary time travelers. ∎

Feature image: Picnic at Deshengmen (德胜门), Beijing. Image Courtesy of the Ruxton Family, University of Bristol Library. (Historical Photographs of China)

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.