The China archive has no shortage of memoirs written by the power-adjacent. Mao’s physician, Li Zhisui, wrote a best-selling tell-all of his famous patient in The Private Life of Chairman Mao (1996). Desmond Shun dished about his time as courtier to the wife of former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao in Red Roulette (2021). Twilight in the Forbidden City, Reginald Johnston’s 1934 memoir of life as an imperial tutor to Puyi, the last Qing emperor, fits neatly on the bookshelf beside these other confidants-turned-chroniclers. Fans of 1980s cinema may remember Johnston as played by Peter O’Toole in Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 Puyi biopic The Last Emperor.

Twilight in the Forbidden City starts with a potted history of the events leading to the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, and Puyi’s abdication at the age of six. This is followed by a much more detailed account of the five years (1919–1924) that Johnston spent as the private English teacher and confidant to Puyi, who was then 13 years old and still living in the Forbidden City. Well aware of our voyeuristic tendencies, Johnston devotes only a few opening chapters to his hot takes on Chinese history — some of which have not aged well (“Had the Boxers appeared a generation later, they would have learned much from the principles and practices of Hitlerite Germany”) — before wisely shifting to what we came for: dishing the dirt on the last emperor and his flunkies.

The Forbidden City of Puyi’s time was not the palace of his ancestors. Still, like Puyi’s own memoir From Emperor to Citizen (我的前半生, Xinhua, 1950) or Sun Yaoting’s The Last Eunuch of China (末代太监孙耀庭传, People’s Literature Publishing House, 2004) — both of which cover the same period of history — Johnston’s behind-the-scenes book gives us tantalizing glimpses from which we can extrapolate what life might have been like for denizens of the Forbidden City in better days:

On the outer side of that gateway lay a million-peopled city throbbing with new hopes and new ideals—many of them, perhaps fortunately, never to be realized … On the inner side of the same gateway were to be observed palanquins bearing stately mandarins with ruby and coral ‘buttons’ and peacocks’ feathers on their official hats and white cranes and golden pheasants on the front of their long outer garments of silk; high court officials in loose-sleeved sable robes, with tufts of white fur (taken from the neck of the sable) as an indication that the wearer was one who had gained the favour of his sovereign.

After the fall of the Qing in 1912, the fledgling Republic of China nominally ruled China beyond the walls of the Forbidden City. Yet inside those walls, Puyi and the remains of the palace staff, including eunuch servants and a few holdover concubines who had served long dead emperors, were still permitted to live as if nothing had changed. Being named imperial tutor was a point of great pride for Johnston, something his memoir takes pains never to let the reader forget:

Another mark of respect shown by the emperor to each of his tutors—even the barbarian from overseas—was to rise when the tutor entered the room. The tutor advanced to the middle of the room, bowed once, and emperor and tutor then sat down simultaneously in their proper places. If the tutor, in the course of the lesson-hours, had occasion to rise for the purpose of fetching a book from a shelf or for any other reason, the emperor rose too, and remained standing till the tutor returned to his place.

Johnston spent nearly his entire adult life in the British colonial service, but it was his five years at the Forbidden City that came to define him. Born in Edinburgh in 1874, Johnston attended the University of Edinburgh and Magdalen College at Oxford before joining the colonial service in 1898. In Hong Kong and Weihaiwei on the Shandong Peninsula, among other postings, he earned a colorful reputation as an eccentric. He despised the expatriate lifestyle, especially pallid attempts to recreate British society and life in colonial outposts. He disliked Christianity, with a special disdain for missionaries, and his lack of hesitation to share his thoughts didn’t make him a delight at dinner parties. His habit of conversing with imaginary friends (one favorite was “Mrs. Walkinshaw”) and including them in conversations at official functions further cemented his status as an odd duck, and did little to advance his career.

During his time as imperial tutor, Johnston dialed up the absurdity. Eyes rolled throughout the foreign community in Beijing whenever they saw him riding in gaudy palace sedan chairs, donning Qing imperial garb, or constantly referencing his titles “at court.” What Johnston viewed as the necessary trappings of a high-ranking tutor to his majesty, others saw as cosplaying a dead dynasty. But whatever others thought of the job or Johnston, he cared very much for his imperial charge and was deeply concerned about Puyi’s education and future. Johnston describes his student as a young man of remarkable aptitude, wit and kindness:

He appears to be physically robust and well-developed for his age. He is a very ‘human’ boy, with vivacity, intelligence, and a keen sense of humour. Moreover, he has excellent manners and is entirely free from arrogance. This is rather remarkable in view of the extremely artificial nature of his surroundings.

Johnston’s efforts to improve the emperor’s daily life led to frequent clashes with palace traditions. For example, during one lesson he discovered that Puyi was shortsighted, and insisted that Puyi get his eyes checked despite protests from Tuan K’ang, one of the last dowager-consorts, that “the wearing of spectacles by emperors is a thing that is not done.” Johnston ignored threats of dire consequences, including one officer’s warning that Tuan threatened to “manifest her displeasure by giving herself a fatal dose of opium.” Johnston writes, with characteristic bluntness, “That was a tragic possibility which I ignored.” The emperor, he asserted, “is going to wear spectacles.”

What Johnston viewed as the necessary trappings of a high-ranking tutor to his majesty, others saw as cosplaying a dead dynasty.

After Puyi married in 1922 and was therefore considered an adult for ritual purposes and in the eyes of the palace staff, Johnston’s role changed. While the former emperor no longer attended his daily lessons, Johnston remained a close friend and advisor, which Puyi discusses at length in his own memoir.

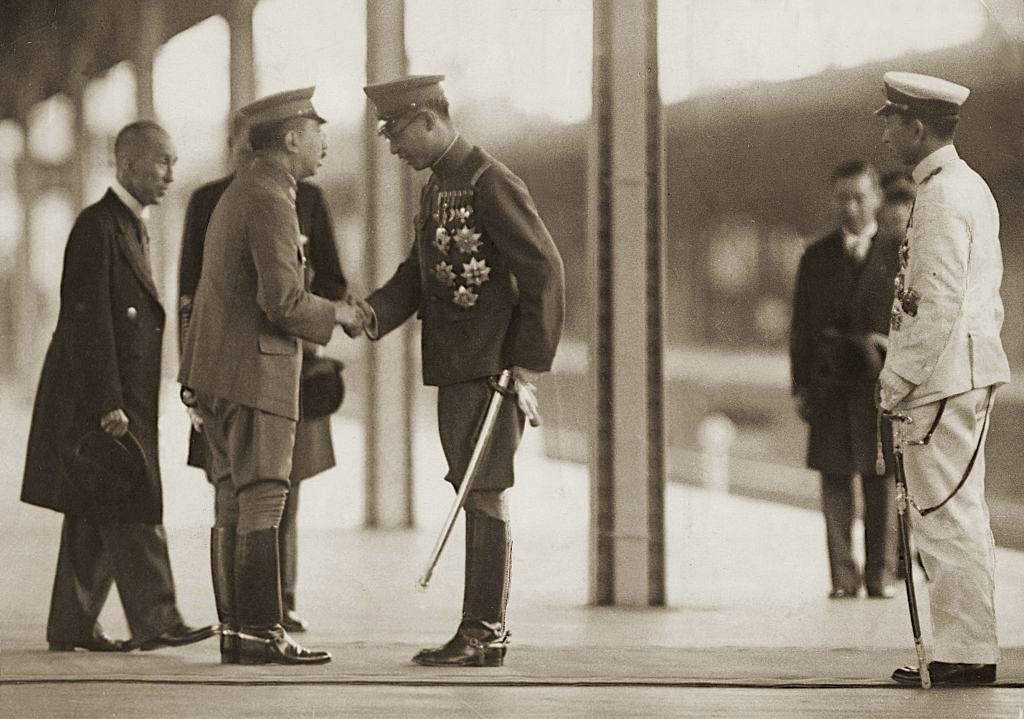

Johnston supported Puyi’s attempts to modernize the administration of his shrinking court during the final years in the Forbidden City, albeit to little success. He also played an ambiguous and arguably self-aggrandizing role in the dramatic events surrounding the imperial court’s final eviction from the Forbidden City in 1924. After the warlord Feng Yuxiang seized control of Beijing, Puyi was unceremoniously ousted and was forced to take refuge in his father’s mansion near Houhai lake, where he had been born and grew up before his ascension to the throne in 1908 — a temporary sanctuary that quickly began to feel like a gilded cage.

According to Johnston, once outside the protective bubble of the imperial palace, Puyi was a pawn in a dangerous game. As soldiers serving rival warlords prowled the hutongs waiting for the chance to take the former emperor into a dubious protective custody, Puyi reached out to Johnston to help him escape to the relative safety of Beijing’s foreign Legation Quarter. Johnston’s rather breathless account highlights favorable elements — notably a fortuitous dust storm that obscured their movements — as he maneuvered between the foreign legations, negotiating first with the British and Germans before securing sanctuary for Puyi at the Japanese Legation. It’s a gripping tale, full of intrigue and adventure. In this telling of it, the fate of the last emperor depended on Johnston’s quick wits and White Savior complex.

The account of the same event in Puyi’s memoir suggests that others aided his escape and reached out to the legations, which Johnston was either unaware of or failed to acknowledge. Nor was Johnston privy to all of the negotiations between Puyi’s family, attendants and officials from Japan by which Puyi ultimately ended up a guest of the Japanese legation, despite Johnston’s claim to have orchestrated the whole affair:

It will be seen from the foregoing pages that the Japanese minister knew nothing whatever of the emperor’s arrival in the Legation Quarter until I myself informed him of it; that it was at my own earnest entreaty that he agreed to grant him protection within the hospitable walls of the Japanese Legation; and that Japanese ‘imperialism’ had nothing whatever to do with ‘the flight of the dragon.’

Puyi’s connection to Japan remains the most problematic part of the book, especially in light of his reemergence as emperor of Manchukuo, a state created under Japanese control in northeast China following the Mukden Incident in 1931. Even after settling in Scotland on a small island in Loch Craignish, Johnston received permission from Puyi to fly the flag of Manchukuo, the emperor’s new puppet state. Throughout Puyi’s coming-of-age story, Johnston seeks to justify how his former pupil eventually found employment, arguing that if China was unwilling to accept an enlightened emperor, then it was OK for Puyi to chase his monarchical dreams in Manchuria.

Johnston asserts: “Even among the educated classes, there has never been a time when the monarchist cause was regarded as dead.” He argues that Manchoukuo is an ancient term for the Manchu Qing dynasty, and suggests that the creation of Manchukuo in 1932 by the Japanese government was not imperial exploitation, but a historically justified move that the Manchus could have made in 1912 if only they had possessed the foresight. Johnston theorizes (or fantasizes) that if the Qing dynasty had retreated to Manchuria in 1912, they might have established a federation of autonomous states — a “Manchuria-Mongolia Empire” — aligned with Japan to safeguard against Chinese encroachment:

Even if the dynasty had felt obliged to relinquish the great Manchu conquests in China, it was still open to the Manchu imperial family to retire to Mukden, its old capital in Manchuria, and to reoccupy the throne of its great ancestor the emperor T’ai Tsung [Taizong].

This echoes the historical arguments that Japanese scholars have put forward to justify the existence of Manchukuo as a “Manchu homeland.” Johnston makes the same case in Twilight in the Forbidden City. Few serious scholars would make the case that Qing distinctiveness equals Manchurian sovereignty. That is one reason why Johnston’s reputation declined after the book’s publication, from an eccentric with a Chinese garden in Scotland to a potential Japanese mole.

Such an accusation is unfair to Johnston, who died in 1938 at the age of 63. He may have been a committed monarchist, but Twilight in the Forbidden City is more the story of a man who found himself close to power and glory — however faded — and made that experience central to his identity, blinding his good sense in the process. It remains a fascinating memoir, providing insight into the inner workings of a court under siege and the life of China’s last (for now) emperor. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.