Two Kinds of Time (1950), American writer Graham Peck’s memoir of living and working in China between 1940 and 1945, begins with an eponymous meditation:

By one Chinese view of time, the future is behind you, above you, where you cannot see it. The past is before you, below you, where you can examine it. Man’s position in time is that of a person sitting beside a river, facing always downstream as he watches the water flow past.

While Peck was not the first or last foreign writer to romanticize Chinese temporal wisdom (consider the oft-quoted canard that Zhou Enlai said it was “too early to tell” the outcome of the French Revolution), the metaphor expresses his wish to be just an observer of China, watching the river of history flow past. But history had other plans. The book covers the era of Japanese occupation, a time when most Chinese people suffered through natural disasters, crushing poverty and fierce political divisions that would lead to civil war. By the time it was published in 1950 — one year after the founding of the People’s Republic of China — the flow of Chinese history had radically changed course.

More than a mere travelogue, Two Kinds of Time is, at different points, an autopsy of the Kuomintang (KMT) regime that fell in 1949; an indictment of American strategic myopia in its China policy of the 1940s; and a timely jeremiad about the dangers of overreach as the world entered the Cold War. The book remains remarkably prescient, offering a trenchant critique of the follies of America’s support for a failing leader who had lost the faith of his people. In the ensuing decades, U.S. policymakers would fall into the same trap in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and countless other American interventions abroad, propping up authoritarian leaders who supposedly “shared our values.”

Two Kinds of Time is an indictment of American strategic myopia in its China policy of the 1940s.

Graham Peck was born in 1914 in Darby, Connecticut. The son of industrialist Irving Peck, he attended all the right schools (Phillips Andover, Yale Class of ’35), then planned to spend a year circling the world, with $2,000 of Daddy’s money supplemented by his income as a sketch artist. He got as far as China. Peck spent two years exploring the country from 1935-37 and wrote a well-received account of his travels, Through China’s Wall (1940). In 1940 he returned to China, now at war with Japan and itself, landing a job with the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI). As an OWI writer and editor based in Guilin and other cities around “free China,” Peck was tasked with spreading U.S. propaganda, combatting Japanese misinformation, and writing positive reports about the war for American readers.

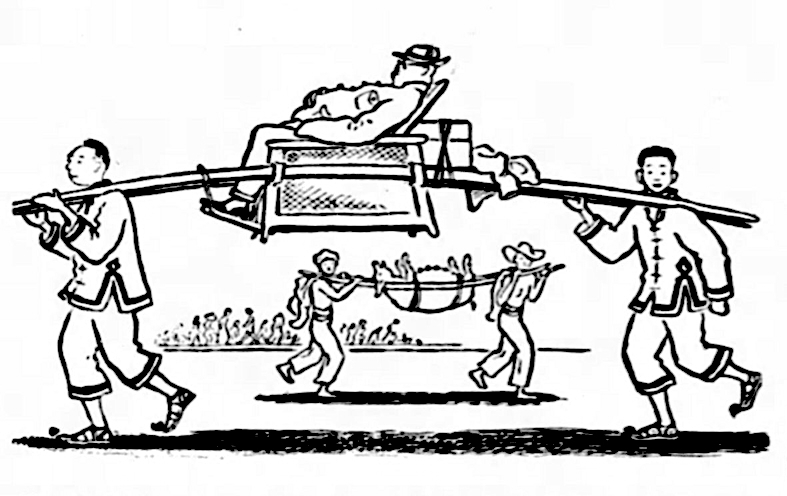

Two Kinds of Time describes China’s unraveling in a series of vignettes that vividly show the lives and conditions of people Peck encountered during his travels around the nation. A keen artist, every chapter also features his own cartoons and drawings, from sketches of the people he met to strategic war maps and battle plans. Peck uses the same gift as a writer, bringing scenes to life on the page with cinematic panache and a sharp eye for turning quotidian details into broader insights. For example, his description of Japanese planes taking advantage of a clear day in the wartime capital of Chongqing:

The urgent sirens howled out, baying up and down the city’s peninsula like a pack of nervous wolves, the last of the little figures on the reddish cliffs across the river vanished into their black cave-mouths, like fleas into the fur of an animal. Chungking on its long humped rock was shaped like a beast crouching to be whipped, an enormous one thinly covered with a pale scurf of houses and ruins.

As a memoirist, Peck is an amiable companion, just catty enough to tell you how he really feels but not so jaded that he’s lost his humanity. He spent time on the front lines of the war, dodging aerial bombardments and seeing famine spread through small villages, as well as in cities such as Luoyang and Liuzhou, which were controlled by a dangerous mix of local satraps, pirate lords, criminal gangs, corrupt officials and rogue military officers. Yet throughout it all, Peck remains keenly attuned to the subtle ways in which people cope with crises, and the resilience of the Chinese people. He notes their “secret smile,” a wry expression that foreigners like himself often miss or misinterpreted:

Even during my first trip to China, I had sometimes suspected that everyone I watched was obscurely engaged in an enormous practical joke. … They seemed determined to look plausibly matter-of-fact, with just a hint of a knowing smile. Because so many odd things had to be done in the wartime capital, they often seemed victims of their own amusement.

Peck is painfully aware that his position with the OWI makes him part of the problem. You feel his frustration at becoming an articulate but ultimately expendable media worker in the U.S. propaganda machine — propaganda that kept saying, from Peck’s perspective, all the wrong things to all the wrong people.

Peck chronicles with dry and, at times, exasperated wit the social and political upheavals that led to the fall of the KMT and the victory of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He concludes that American aid to the KMT exacerbated the economic and military problems it was intended to solve. Moreover, by aligning itself with a deeply unpopular government, the U.S. undermined its credibility in China, leading to the dramatic deterioration in U.S.-China relations after 1949. It turns out that backing the KMT — who Peck believed converted American largesse into currency inflation and military defeats — wasn’t the masterstroke of containment policy U.S. leaders hoped it would be. Instead, Peck writes:

Our aid to the Kuomintang firmly identified America with the last and worst years of China’s collapsing feudalism. Since there has been so much argument in America about China policy, most Americans do not realize that in China it never looked as if we were in doubt. In the post-war period, all politically minded Chinese were aware that the Kuomintang would no longer be so dominant if it had not been for our help.

Peck argues that the KMT regime was sclerotically beholden to the personality and foibles of its leader, Chiang Kai-shek. The generalissimo and his inner circle were intent on selling a dumpster fire of pseudo-democracy, nascent fascism, social micro-management and incompetent authoritarianism that still managed to be less than the sum of these parts. The more significant problem was that American policies, both before and after the war, tied the U.S. to Chiang like an anchor. For Peck, this relationship was a case study of why choosing friends just because they happen to be our enemies’ enemies is a bad idea. As Peck notes:

As a nation we simply could not recognize that in China a revolution was smoldering into life by spontaneous combustion. … Our later panicky attempt to blow it out, when it had become both Communist-fueled and definitely afire, only added strength to the spreading flame. Our interference — especially the lethal weapons we gave to the Kuomintang — also intensified the anguish of the Chinese people. This causes more anti-Americanism in present-day China than any amount of Communist propaganda ever could.

Although U.S. officials prevented Peck from following in the footsteps of Edgar Snow and other foreign journalists who made the trek to the Communist Party base in Yan’an, he spent enough time in China to reach his own conclusions about the CCP and their potential ascendence to power. According to Peck, U.S. policymakers spectacularly underestimated the powerful social and political forces that ultimately propelled the CCP to victory.

Every chapter also features Peck’s own cartoons and drawings, from sketches of the people he met to strategic war maps and battle plans.

In 1950, with the Communist victory still fresh and China’s future uncertain, Peck could not have foreseen the arc of the Chinese Revolution, including the utopian hopes and catastrophic missteps of the Mao era, never mind the transformations of more recent decades. Nevertheless, he intuited the open-ended nature of the unfolding saga, grasping the unique Chinese revolutionary experience and its likely protracted evolution:

I think it is just possible that Chinese Communism may be something new and unique, based on the same ideas which produced Western communism, but growing in such different circumstances, among a very un-Western people, that its final form is unpredictable. The Chinese revolution has taken a century to work up to the collapse of feudalism, so I suspect that if it meets no outside interference, its later stages will spread over at least one more century.

Peck was rightfully suspicious of the CCP’s potential for authoritarianism and ideological rigidity, but suggested that their working-class roots and approach to rural mobilization made it the only viable contender for power other than the KMT. Yet, as with other American journalists working in China, notably Theodore White, co-author of the influential book Thunder Out of China (1946), Peck yearned for the emergence of a centrist “third way,” a desire as chimerical as the view of Chiang Kai-shek as the savior of China.

When Two Kinds of Time was published, the hysteria of “who lost China?” (a repeated lament in Washington) was already a fever dream of Cold War paranoia — a political trip fueled by ego, political ambition and dubious patriotism. Peck was among the few posing the sensible question: Was China ever ours to lose? The book combines literary verve and reported detail with a clear-sighted analysis that makes modern readers wonder, “Why didn’t we listen to this guy?” Perhaps that’s why it failed to reach a wider audience, despite Peck’s foresight. In the calcifying ideological climate of 1950s McCarthyism, there seemed to be little stomach for someone who had the temerity to ask: What if we’re wrong?

75 years later — at the inauguration of another U.S. administration that may struggle to set a coherent China policy — Peck reminds us that the loudest voices in the room are often just filling the silence. The truth sits quietly, waiting for someone to write about it. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.