Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: The Beast in the Clouds: The Roosevelt Brothers’ Deadly Quest to Find the Mythical Giant Panda by Nathalia Holt (Atria, July 2025).

On November 8, 2023, three of Washington D.C.’s most beloved Chinese residents were forced to leave the United States. That morning, Tian Tian, Mei Xiang and their three-year-old son Xiao Qi Ji were put in crates and loaded onto an airplane. China had called them back to their homeland, ostensibly to chide the U.S. government in the wake of tense relations, by denying American citizens the right to view the giant pandas at D.C.’s National Zoo.

Their departure marked a hiccup in America’s long-standing love affair with pandas, one that has endured for the better part of a century. The fascination reached a fever pitch in 1929, after Ted and Kermit Roosevelt, the eldest two sons of President Theodore Roosevelt, returned from an expedition to Asia as the first white men to successfully track down the mysterious black-and-white bear and bring back a specimen for America to admire. Their harrowing journey into what were then the borderlands of China and Tibet, as well as the panda craze it helped generate in the U.S., is the topic of Nathalia Holt’s The Beast in the Clouds (Atria, July 2025).

Americans had long been familiar with brown and black bears, fearing their attacks and keeping them captive. A new plush toy, the “Teddy bear,” was named after President Roosevelt in 1902. Yet the panda was not nearly as well understood. Descriptions in Chinese literature spoke of a mythical creature that ate copper and iron, and there was scant mention of the panda in their historical records. In the West, there was doubt about whether the animal was even real. In 1869, Chinese hunters had brought a lifeless cub to a Chengdu-based French missionary, who skinned it and sent the pelt to experts in Paris. They were not convinced they were looking at a new species. Then, in 1916, German explorers claimed to have been given several dead pandas and a live cub, but their failure to send specimens back to Europe did not dispel the skepticism.

It was not until 1919, when another missionary purchased a panda skin and donated it to New York’s American Museum of Natural History, that the animal’s existence was considered to be proven. A flurry of explorers set off for Asia to find the panda, to describe its habitat and diet, and to kill one themselves and bring it back home. They all returned empty-handed. By the 1920s explorers, scientists and hunters had filled the museums of America with taxidermied wildlife from all over the world. But the panda remained elusive.

At the time, hunting wild animals — however endangered they might be — was considered an act of conservation, for it aided scientists in their understanding of unknown species. President Roosevelt, an avid hunter who brought back many a pelt from hunting trips to Africa and Brazil, wrote in his book Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter (1908): “Wild animals only continue to exist at all when preserved by sportsmen.” Museums agreed with this mindset, and frequently funded expeditions. When his sons set out to try their luck tracking down the panda, in December 1928, they did so at the behest of Chicago’s Field Museum.

At the time, hunting wild animals was considered an act of conservation, for it aided scientists in their understanding of unknown species.

The Roosevelts entered China from Burma, a route known as “the back door” for its lack of border guards. The then young Republic of China had been cut into pieces by local strongmen, blighted by opium addiction and one year into a civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists. More than once, the brothers’ party — which included two naturalists, a multilingual interpreter, a rotating cast of local guides and hunters, and mules — had to deal with groups of armed men. But the brothers “were blinded by their position in society,” Holt writes. Privilege made them unaware of the dangerous terrain their group was passing through.

Their initial destination was Tatsientlu, present-day Kangding in Sichuan, where the panda pelt donated to the New York museum had been purchased. This meant first traversing the Himalayas, with its winter weather and lack of oxygen. At night, the brothers woke up choking on thin air. On multiple mornings, they discovered their mules had run off, taking their supplies with them. The cold clung to them day and night.

Along the way they hunted or trapped any animal that could be of interest to the museum, but a panda was the big prize. When they arrived in Tatsienlu, they showed illustrated plates of the bear to locals, but none of them had ever seen such an animal. The brothers had little information to go on; nobody in the West knew to look in bamboo forests. Scientists had also surmised that, as the panda was a bear, it must be strong and aggressive — perhaps, given its white fur, as fearsome as a polar bear. This imagined fierceness made killing a panda all the more alluring to men like the Roosevelts.

By March, when the brothers had been in China for over two months, they had yet to meet anyone who had ever seen a panda. In another month, the monsoon season would make tracking animals nearly impossible. Their luck turned when they met a hunter who had recently killed a panda, and who would sell them its pelt. The pelt was dry, old and teared, making it of limited value. But at least it gave them a better idea of where to find one themselves. They came across panda scat, claw marks and coarse white hairs, but — despite struggling through dense forests for days, including what Ted described as “the hardest day’s hunting I had ever spent” — they found no bears. Though Holt draws out such hunting mishaps for dramatic effect, the brothers seem to have gotten on fine otherwise, having collected some 5,000 birds and 2,000 mammals, and identified 19 new species.

Their next stop was the southern region of Sichuan province that is home to the Yi ethnic group, which was where the French missionary had obtained the skin of a panda cub in 1869. In contrast with the fearsome beast the Roosevelts thought they were chasing, the Yi considered the panda a mild-mannered “supernatural being, a sort of demi-god,” and were initially reluctant to help them kill one. Local hunters only joined their party thinking it was easy money for a fool’s errand. They knew pandas were near impossible to find, especially now that the seasonal rains left forests both muddy and noisy.

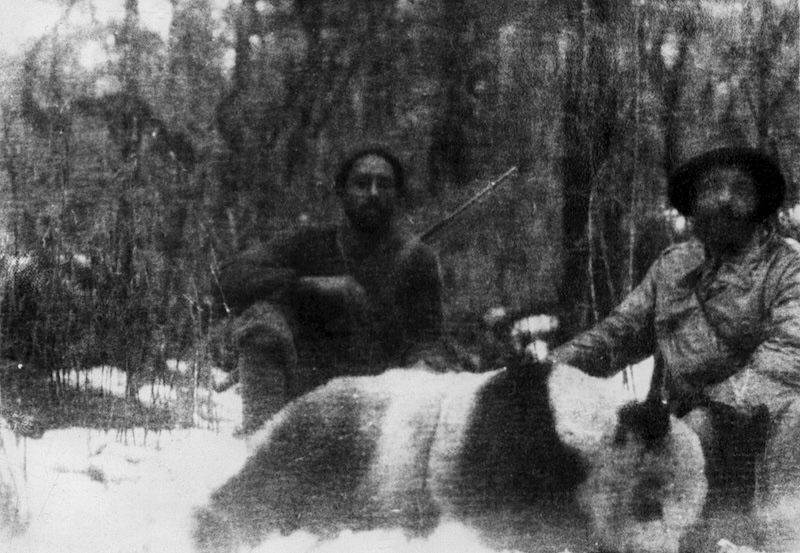

But the brothers did, finally, find and kill their panda. As recounted by Holt, Kermit was alerted by a strange noise and followed his Yi guide to a giant spruce with a hole in its trunk, out of which the black-framed eyes of a panda emerged. Having vowed to pull the trigger together with his brother, Kermit waited for a guide to fetch Ted — a wait during which he observed the almost otherworldly animal he had failed to find so many times before. Once Ted arrived, they raised their rifles, and fired.

Up to this point Holt’s book is an adventurous yarn — one that touches superficially on social issues of the early 20th century, but is mostly interested in colorfully describing the drudgery of stalking through foreign lands — whose outcome is not in question if you’ve read the book’s synopsis. But the Roosevelts finding and shooting what turned out to be a “gentleman” of an animal gives their story a surprising twist. They found little joy in bringing their arduous journey to a successful close. Instead, the panda’s peacefulness challenged their beliefs about big-game hunting.

In the summer of 1929, after Kermit rushed home to save his company from succumbing to the Great Depression, and another of Ted’s expeditions was cut short by a life-threatening bout of malaria, American newspapers celebrated the brothers’ catch. The Roosevelts’ two pandas — the one they shot, and the pelt they bought — were extensively studied by scientists, before being exhibited in Chicago’s Field Museum in 1931. But, Holt writes, “While panda-mania began sweeping the United States, the Roosevelts grappled with their own role in unveiling the animal.” Kermit’s regrets even made him join the New York Zoological Society, “dedicating himself to the animals he once hunted.”

Scientists had surmised that, as the panda was a bear, it must be strong and aggressive — perhaps, given its white fur, as fearsome as a polar bear.

It was hard to convince the world of their misgivings. The success of the Roosevelt brothers’ panda hunt spawned new expeditions by adventurers who hoped to bring one of the bamboo-munching bears back alive. The first to succeed was Ruth Harkness, who brought a panda cub back to the U.S. in 1936. In The Lady and the Panda (Random House, 2006), Vicki Constantine Croke describes how that only heightened America’s interest. The cub, Su-Lin, was on the front page of the Chicago Tribune for nine days straight, and drew 53,000 daily visitors to its zoo, a mark never reached again.

Yet for Harkness, too, panda hunting was an experience that gave her second thoughts. In the following years, Harkness returned to China to get Su-Lin a companion, Mei-Mei, and then again, when Su-Lin died, to “save Mei-Mei from loneliness.” Waiting for her in Chengdu was a third panda, Su-Sen. But after Harkness arrived, Croke writes, she “was disgusted by what was happening.” The Western craze for pandas that she and the Roosevelts had unleashed had translated into a local gold rush for the animals, with Western missionaries as middlemen. Many of the animals died en route, and the solution was simply to capture more. Two valleys in Sichuan, Harkness learned, had already been hunted clean. When a fourth panda brought to her turned violent in captivity and had to be shot, Harkness had an epiphany: Pandas belong in the wild. She would return Su-Sen to the bamboo forests.

This view that wild animals should be protected rather than hunted — a realization the Roosevelts and Harkness both came to after their expeditions — would eventually win out, in part due to the animals they hunted. The author and filmmaker Chris Catton said in his 1990 book Pandas that Su-Lin “did more for the cause of nature conservation than most humans could hope to achieve in a lifetime.” The giant panda became the worldwide symbol of wildlife conservation, and a species for which little expense is spared to ensure their survival. From a low point of about 1,100 individuals in the 1980s, the wild panda population has rebounded to nearly 1,900 animals, a level healthy enough for the species to be classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as “vulnerable” instead of “endangered.”

Pandas in captivity have nevertheless remained a main attraction for zoos all over the world. The initial rush of pandas brought to the U.S. in the 1930s and 40s had all died by the 1950s, when China had closed again under Mao Zedong. Americans had to wait until 1972 to resupply, when China sent a pair of pandas to Washington D.C. following President Richard Nixon’s historic trip to Beijing that laid the ground for the restoration of Sino-U.S. relations.

Beijing has continued to use pandas for diplomatic purposes, keeping ownership of the animals it loans to foreign zoos for hefty figures. In 2023, when China recalled Tian Tian, Mei Xiang and Xiao Qi Ji in what one commentator called “punitive panda diplomacy,” it took a summit between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping for new panda loan agreements to be reached. Washington D.C.’s National Zoo presented newly arrived Bao Li and Qing Bao to the public in January of this year — a relief after a panda-less 2024 had seen visitor numbers at the zoo drop by 16%.

Meanwhile, at the Chicago Field Museum, the Roosevelts’ pandas — as well as Harkness’ Su-Lin — remain on display as taxidermy. The bears are no longer as mysterious as they once were, but are just as endearing. They also hold the distinction of being animals whose tragic fate of being captured or shot aided the future conservation of their and other species. ∎

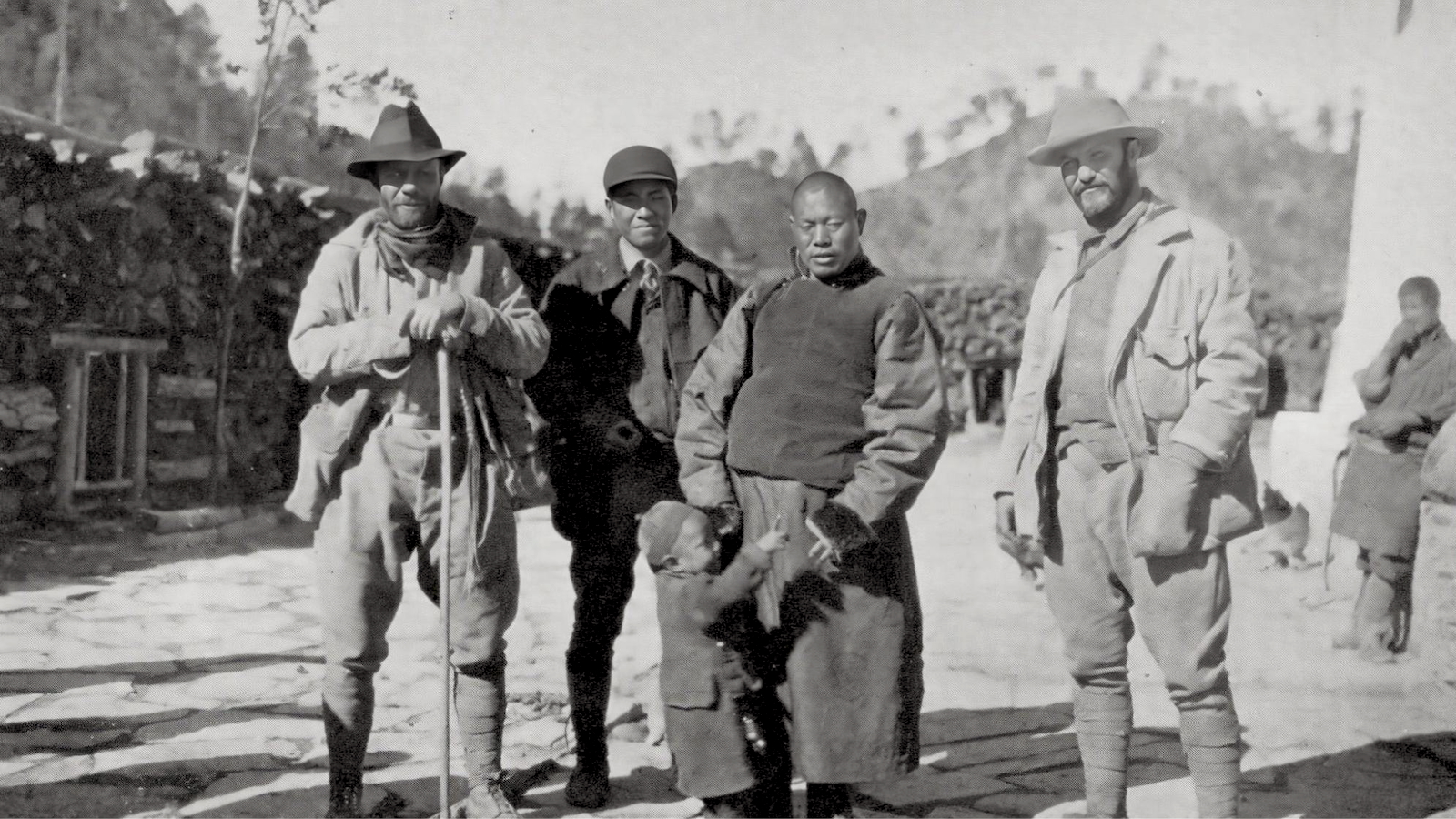

Header: Members of the hunting party. Left to right: Kermit Roosevelt; the interpreter Jack Young; local lord Chang Ta Li, with his son; Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (Suydam Cutting)

Kevin Schoenmakers is a New York-based freelance reporter and editor. He was previously a founding editor of Sixth Tone in Shanghai, China correspondent for Dutch news wire ANP, and Features Editor at Rest of World.