Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: Joseph Torigian, The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping (Stanford University Press, June 2025).

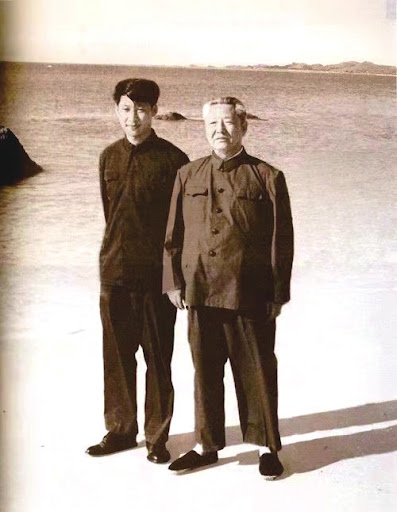

In 1972, the 21-year-old Xi Jinping was in conversation with his father, Xi Zhongxun. The elder Xi, who had spent the past several years in exile as the victim of a political purge, saw that his son was smoking a cigarette, and asked him why he had taken up the habit. “I am depressed,” replied Xi Jinping, admitting it was a depression caused by the hardships the family had suffered while his father was away. The elder Xi was silent, then declared: “I give you permission to smoke.” A little while later, he presented his son with a pipe. While Xi Jinping supposedly gave up smoking in the late 1980s, there is persistent speculation that he still smokes to this day.

There’s a lot to unpack in that encounter, which is just one of the fascinating scenes in Joseph Torigian’s outstanding book on the life of Xi elder, The Party’s Interests Come First. Xi Zhongxun was a highly exacting father, and his query about his son’s smoking was likely to have been harshly phrased. Yet the reply must have brought to mind just how much his political rise and fall had affected his children — above all his daughter Xi Heping, Xi Jinping’s half-sister, who took her life after being persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. While the book does provide interesting insights into China’s current leader, however, it would be a shame to let the prominence of the son be the only reason to appreciate the story of the father.

There are certain pieces of accepted wisdom about Xi Zhongxun: that he was relatively liberal when it came to the treatment of ethnic minorities; that he was instrumental to economic reform in the 1980s; and that he had qualms about the treatment of democracy protestors in 1989. Torigian acknowledges these assumptions and then adds detailed analysis to them all, to paint a portrait of a man whose ambivalence about how to move the communist revolution forward reflects complexities that his son rarely projects in the present day.

It would be a shame to let the prominence of the son be the only reason to appreciate the story of the father.

The book covers Xi’s life in meticulous detail. It starts with his birth in 1913 in Shaanxi, a province that would later host Mao Zedong’s legendary Yan’an base where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) consolidated power in the 1940s. He joined the CCP’s youth league in 1926, and went on to become one of its heads in the 1930s. In one of the early examples of the factionalism that would mark his career (and that of so many senior Party members), Xi was purged because of his associations with Liu Zhidan and Gao Gang, two key members of the leadership who fell out of favour at the time. He was freed from prison within a couple of years, but the incident would blight him for years to come.

During China’s second war against Japan (1937-45) and the Chinese civil war that followed (1945-49), Xi Zhongxun remained in the northwest, his significance and power growing as the region became the base for the growing Communist revolution. Once the CCP took power in October 1949, Xi was heavily involved in some of its most important policy decisions of the 1950s. He expressed doubts about the violence of land reform in its early phase, suggesting that many supposedly rich farmers had been judged too harshly. He also sought to bring Hui Muslim and Tibetan leaders into the CCP fold, and in 1954 held a famously friendly set of meetings with the (current) Dalai Lama. He became the Party’s propaganda chief in 1952, and was later enshrined as one of the Party’s “Eight Elders” (八大元老), as well as being among the elite set of red families who lived in privileged circumstances in Beijing.

There are many reasons why Xi Zhongxun is remembered as a significant figure in the formation of the Party. One (better recalled in the West than in China) is his friendly relationship in the Mao era with at least some ethnic leaders, notably the Panchen Lama — the second most senior figure in Tibetan Buddhism, who was friendly to Beijing but also horrified by the abuses committed by Party members against Tibet’s people and heritage in the 1950s. In their 1962 talks, Xi attempted to soothe the Panchen Lama’s anger over the persecution of Tibetans and the destruction of Buddhist cultural items, declaring: “Vent your anger … I welcome you to vent your anger here. Every time there is a fight, then unity becomes much better.” But Xi’s relationship with the Panchen Lama proved no match for the hardline views of Mao and Deng Xiaoping, who were united in their view that the Tibetan leader had been given too much leeway. During the Cultural Revolution, Zhou Enlai would condemn Xi as a “rightist” who had accommodated the Panchen Lama “without principle.”

On 27 September 1962, the last day of the CCP’s 10th Plenum, disaster struck. That day, two committees were established to make a thorough investigation of two senior figures, Peng Dehuai (the former defence minister who had been purged after daring to contradict Mao in 1959) and Xi Zhongxun. The proximate cause of the investigation was a novel that was published about the life of Liu Zhidan, Xi’s old revolutionary comrade and a rival of Mao. The author was Li Jiantong, wife of Liu’s brother, and the “novel” was based on over a hundred interviews with old revolutionaries who remembered the Party’s early factional battles. As propaganda chief, Xi had repeatedly sent it back for revisions, but eventually agreed to its publication in 1961. The book was explosive because it implied that Liu Zhidan’s role was much more important in the formation of the Party than the Mao-centric version of official history. By 1962, Party organs were making it clear that they regarded the book as subversive literature, and the Party Plenum ended that year with an announcement that Xi was under investigation.

Xi blamed Kang Sheng for his downfall — the terrifying Moscow-trained security chief who had been prominent during the Rectification movement in Yan’an in 1942-44, now a senior Politburo figure. But there were also wider currents flowing within the Party in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward. Torigian gives blow-by-blow accounts of the factional battles that underlay the purge of Xi Zhongxun, but their overall effect became starkly clear. Xi was quickly removed from leadership positions and placed under arrest. Four years after the purge, the situation worsened as Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. Taken to Xi’an in late 1966, Xi was made to suffer painful and humiliating treatment as Red Guards forced him into the “jet plane” position (head bent down and arms stretched up for long periods), subjecting him to the same treatment as other purged leaders such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

In 1966 Xi Jinping, now aged 13, was essentially held captive at the Beijing Party School, where his own mother, Qi Xin, participated in struggle sessions against him while he wore a heavy steel cap designed for adults. On one occasion, when he ran away from the school to find his mother to ask her for something to eat, she not only refused him but reported him to the authorities, who placed him in juvenile detention. Later, Qi Xin was assigned to a reform-through-labor May 7 Cadre School in Henan province, and in 1969 Xi Jinping was sent down to the village of Liangjiahe in Shaanxi province for “re-education,” where he remained until 1975. (Xi Zhongxun’s other children — three with Qi Xin and three from a previous marriage — were also persecuted or exiled as the family fell apart.)

It’s often observed that Xi Jinping is likely to be the last leader of China who came of age during the Cultural Revolution. His father certainly shared that view. “The Cultural Revolution honed my children,” Xi Zhongxun remarked in 1997. Xi Jinping’s fixation on order above all could be plausibly connected to his childhood experiences. “During eight years of exile, persecution and incarceration,” Torigian notes, “Xi Zhongxun did not see his wife or children.” That meant, of course, that his children also did not see him, and it’s clear that those years had the most profound effect on the young Jinping.

In the liberalizing period of the 1980s, Xi also drew on his experiences in the 1950s to resolve the deep anger created in Tibet by Chinese rule, not least during the Cultural Revolution. In 1982 he received a visit from the Panchen Lama, and spent the next years trying to collaborate with the Tibetan leader. There was no doubt that Xi was firmly attached to the Party line, declaring that the CCP “cannot be tricked” by the “Dalai clique,” but he maintained that the Party had to accommodate at least some aspects of Tibetan identity and heavily criticized Yin Fatang, Tibet’s Party chief who was cracking down on religious activity in the region.

However, the fall of the liberal General Secretary Hu Yaobang in 1987 brought the more open era to a close. Xi was the only senior figure at Hu’s denunciation meeting to defend him. This does Xi credit, but it also brings to the fore the central ambiguity of his character: his liberal instincts were real, but his loyalty to the CCP ultimately won out. The book’s title, The Party’s Interests Come First, refers to a written slogan (党的利益在第一位) on a white cloth presented to Xi by Mao at a major conference over the winter of 1942-3, which Xi kept despite being purged by Mao later. As Torigian observes, however sympathetic Xi might be to liberal individuals, in the end, dangxing (党性, “Party-ness”) would always prevail.

Ultimately, Xi was not close enough to Party secretary Zhao Ziyang to fall from grace alongside him in the turmoil of 1989. But he slowly faded from power. By the early 1990s, Xi had retired, although he made occasional appearances at official events. He died in 2002, wracked by paranoid delusions after a period of mental decline. His second wife Qi Xin, mother of Xi Jinping and his siblings, is still alive as of spring 2025, though she appears to have had little public role.

This is the central ambiguity of Xi Zhongxun’s character: his liberal instincts were real, but his loyalty to the CCP ultimately won out.

Ultimately, the potential effect of Xi Zhongxun on Xi Jinping is one of the most revealing elements in the book. The story about the elder Xi giving his son permission to smoke is in some ways unusual behavior for him. Far more frequent are examples of his harsh treatment of his children. “In part because of his fixation on hardship as a character-building exercise at home,” Torigian notes, “Xi Zhongxun was a brutal disciplinarian.”

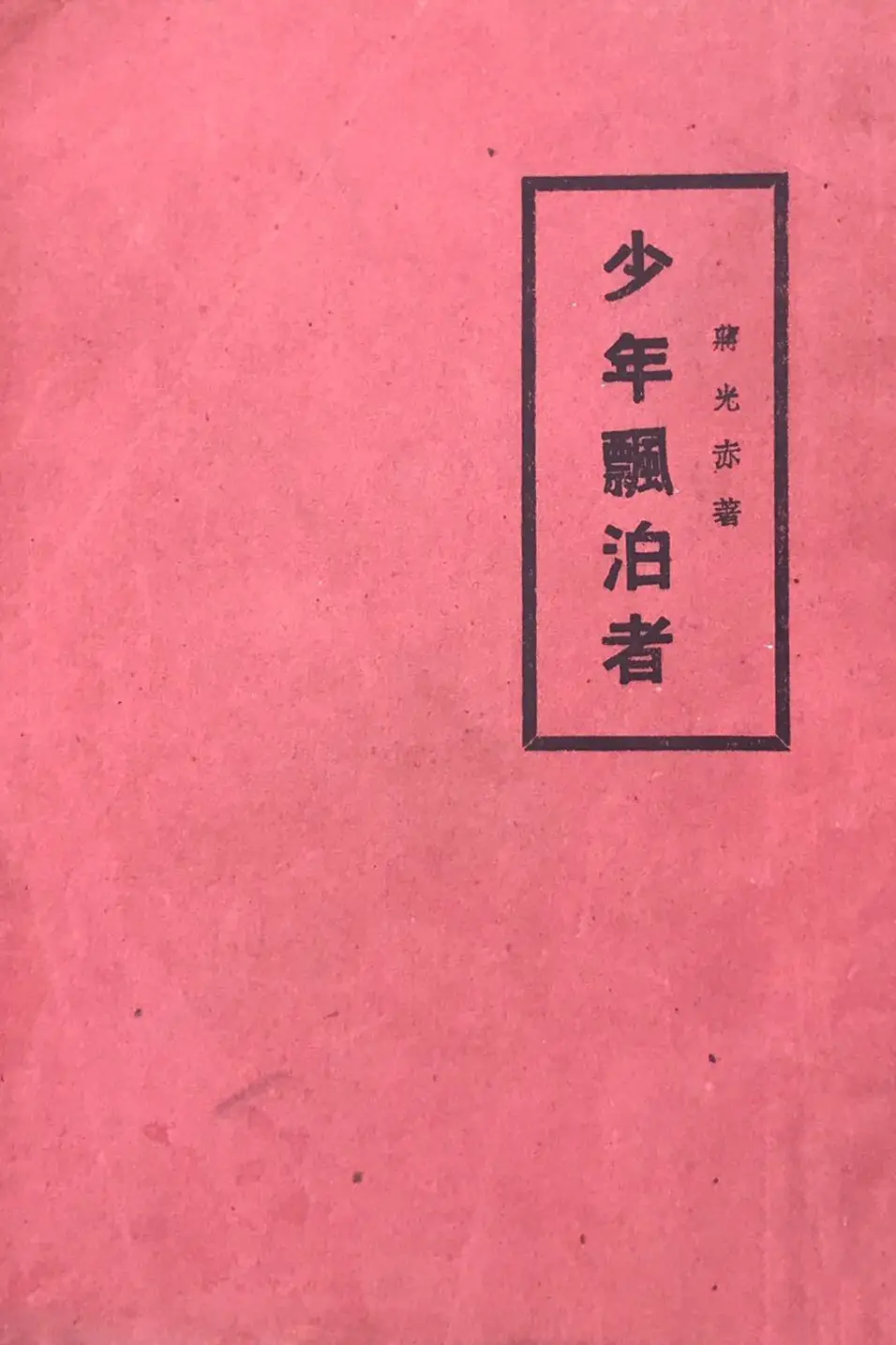

This attitude was shaped at least in part by his own harrowing experiences as a boy. Born in 1913, his parents died when he was very young, and he grew up in the midst of starvation and disease in the 1920s. He found some comfort in romantic Chinese novels — just as Mao Zedong did, who favoured classics such as Outlaws of the Marsh. One of Xi’s professed favorites was the leftist novelist Jiang Guangci’s 1926 novella The Young Wanderer, a picaresque tale of a young revolutionary who comes of age in turbulent times. The Soviet tropes of the story, with its romantic nihilism and anarchist hopelessness as opposed to commitment to a cause, were fascinating to many Chinese revolutionaries at the time who wanted to take the same path.

Xi Zhongxun drew on Jiang Guangci’s novel when developing his own character, and his son in turn drew on Russian literary examples as models. In 2013, as Torigian notes, Xi Jinping told a group of Russian academics that he modelled himself on a “puritanical” character in Nikolai Chernyshevskyy’s classic 1863 novel What Is To Be Done?, who sleeps on a bed of nails. Xi Jinping never did this, but he did walk through atrocious weather as a way of hardening himself. Today, pundits reflect on why there seems to be a bond between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. The shared influence of Russian literature may have something to do with it. Xi’s strictures against what he seems to regard as effeminate men seems also to nod at an era of a rough, assertive revolutionary masculinity. Perhaps, again, his father’s example was important.

Yet it’s also not outlandish to wonder why Xi Jinping isn’t more like his father. After all, many senior Party figures seem to have supported him on the grounds that he would be a reformer, or that he would not go against his father’s legacy. This assumes that children will necessarily lead like their parents (arguably proven false by George W. Bush, among others). More importantly, it also assumes that some aspects of Xi Zhongxun’s leadership style are relevant and others are not.

The idea that the son is not like the father is based on the idea that Xi Zhongxun was tolerant of ethnic minorities, supportive of liberal figures within the Party and a champion of market reforms. In contrast, Xi Jinping has cracked down on the rights of ethnic minorities in China, condemned liberal political tendencies, and pushed back hard at private entrepreneurs. Yet what they share in common is a joint declaration that the Party’s interests do in fact come first. In Xi Jinping’s case, this is refracted through a personality cult that his father, not being the top leader, did not have a chance to benefit from. But the younger Xi’s Party-state is still a system of governance where individual power is magnified because of the Party, not despite it.

This stress on the Party above the individual emphasizes a key historical question: why did the Communists succeed in seizing power in China, when their rivals failed? If Xi Zhongxun had not been Xi Jinping’s father, would we still be interested in his biography? The answer is a resounding yes, because his life encompasses precisely the complexities that defined and also tore apart the Communist revolution. Xi Zhongxun learned early on that the CCP was riven by suspicions and rivalries, when his association with the purged revolutionary Liu Zhidan in the 1930s came back to haunt him three decades later. Yet this pattern of suspicion is hardly surprising for a Party forged in secrecy, constantly on the alert as to whether there were spies in its ranks. That pattern persisted through their victory in 1949 and into the present day.

Xi Zhongxun’s life encompasses precisely the complexities that defined and also tore apart the Communist revolution.

The richness of Torigian’s research and writing make this work an exemplary study of Party history. The only very small quibble I can make is that its detailed and evidently hard-won sourcing is not always easy to follow. It’s clear from the footnotes and bibliography that Torigian has read a wealth of Chinese sources, including essays by Xi Zhongxun and published materials from the Central Party Archives. However, there is no detailed discussion of the various sources used and how to assess them (partly, as Torigian’s acknowledgements make clear, to protect those sources).

Anyone who works on Party history will know that this is a fraught area, not least because the CCP itself discourages any published research that doesn’t fit with current ideological currents, and published materials can vary from ultra-secret to widely available. The 1990s and early 2000s were a relatively freer era, when remarkably frank documents and memoirs about the Party’s history were released, but that stream appears mostly to have dried up; many online sources that were available in the 2010s are now offline. It is doubtful whether more Party histories such as this will be written in the near future, not least because access to the deepest goldmine, the Central Party Archives, is highly unlikely to be opened to outside scholars anytime soon.

Torigian’s book does an excellent job of showing the range of views that the Party could accommodate, and the limits on them. Xi Zhongxun was a relative liberal on ethnic matters, and this did make him notable in comparison with Mao or Deng. Yet he was also, in the end, compliant with the Party’s demands. He was supportive of economic reform, but not to the extent (unlike Hu Yaobang) of wondering whether the system needed liberal political change too. In fact, very few Party insiders defined themselves outside the wider mainstream of the Party’s interests. To that extent, Xi Zhongxun’s life defines the pathway of what it meant to be a relative moderate in a radical revolutionary Party, or if such a middle path is possible.

Beyond that, Xi’s story stands as a necessary reminder that all political stories are also human stories. Understanding the father’s views does not simplistically help us to understand the son’s. They are clearly very different thinkers, with the latter clearly far less liberal. But the dialectic between them (to use a Marxist term that both might approve of) does matter. The martinet who was outraged by his son’s turn to cigarettes, but who softened enough to buy him a pipe, was navigating a range of commitments.

What did it mean to be a revolutionary, a person who valued personal discipline, and a father who had disappeared when his teenage children needed him most? Xi Zhongxun was committed to a revolution, even as he knew that the revolution could devour him. His very uncertainty about his fate perhaps made him even more committed to exercising control in those domains where he held it, such as his family life.

Next time you see the confident figure of Xi Jinping on TV, dressed in a black suit, speaking at a Party plenum or at a G20 summit with a typically reserved expression on his face, think of him as a child still working through his relationship with his father. Don’t take this reviewer’s word for it. Xi Jinping gave his own verdict on his father in 2013, to a group of visiting Russian sinologists: that Xi Zhongxun was the “supreme life example.” ∎

Rana Mitter is a historian of modern China. He is ST Lee Chair in US-Asia Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School, and previously was Professor of the History and Politics of Modern China at Oxford University. He is the author of multiple books on 20th century Chinese history, most recently China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism (2020).