Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Welcome to “What China’s Thinking,” our new interview column on thunderous ideas out of China. When China Books Review launched, we noted that “the average educated Chinese reader knows far more about America and Europe than the equivalent Western reader does of China.” This column aims to ameliorate that sorry state of affairs. We’ll be publishing regular long-form conversations with Chinese public intellectuals — thinkers, writers and doers — on the ideas that impassion them, the books they’re writing, and their insights into contemporary China.

Born in Chongqing, I’m a bilingual journalist living in New York after a decade working for Southern Metropolis Daily, The Beijing News and The New York Times. Time and again, I have seen complex debates within China ignored, misread or forced to conform to preset narratives when they are brought into the English-speaking world. Through lengthy one-on-one conversations in Chinese — translated and lightly edited below — I will present what intellectuals in China are truly thinking, to the best of their ability to speak freely and in their own authentic words. Together with Na Zhong’s column “What China’s Reading,” we offer a window into a changing society that is not always easily visible from the outside.

— Yi Liu

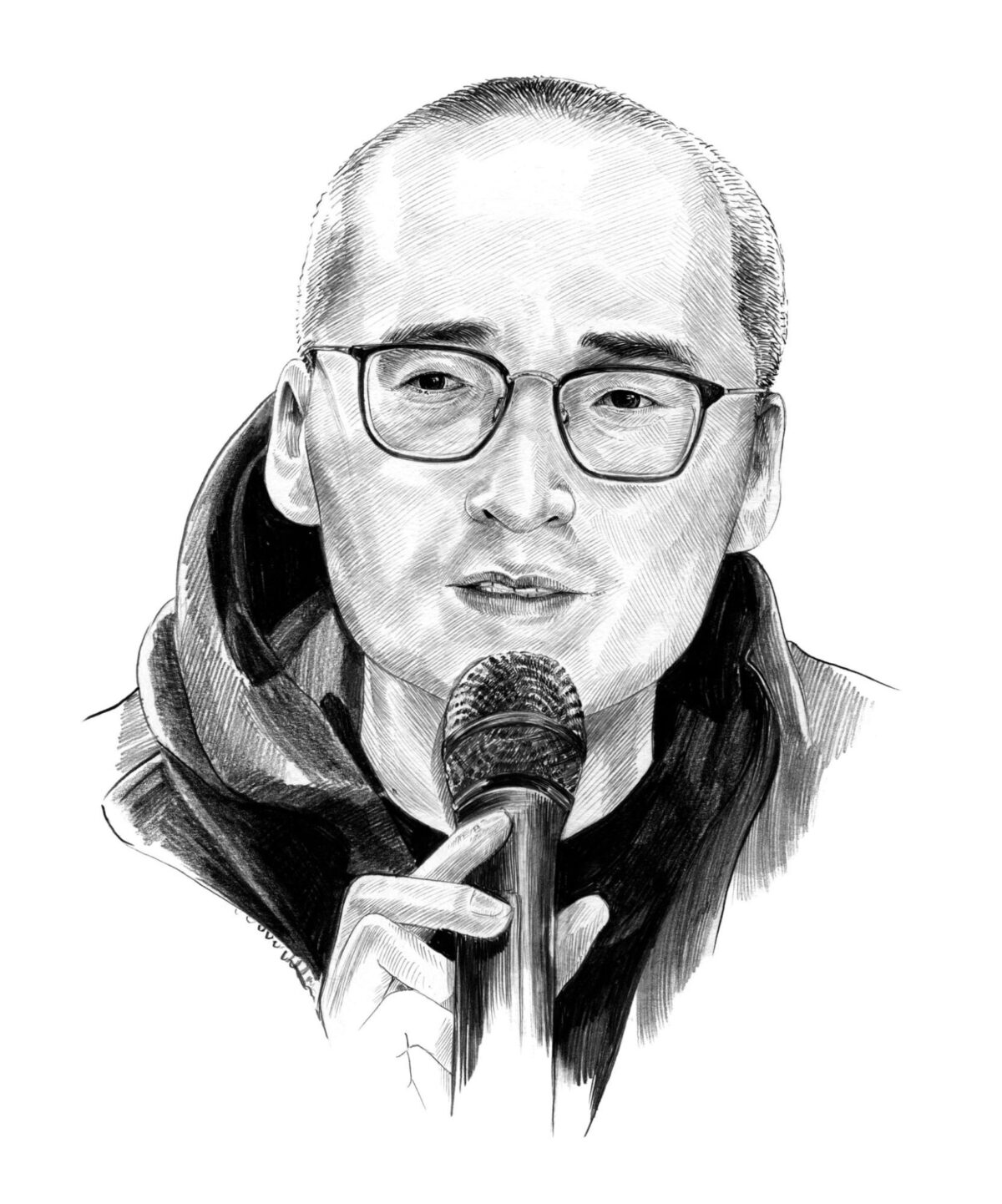

Zhang Feng (张丰) is a Chengdu-based writer, editor, prolific commentator and bookshop owner. Born in 1978 in a rural village outside of Zhoukou, Henan province, Zhang studied Chinese literature at Ocean University of China in Qingdao. While a graduate student in Beijing in the early 2000s, his thesis advisor told him of her experience at the Tiananmen protests. Inspired, he decided to pursue a career in journalism — which he saw as an endeavor in telling the truth. He worked as an editor at Chengdu Business Daily until 2019, when he shifted his writing to a public account (公众号) on the messaging and social media app WeChat — a rising form of new media in China.

His essays on WeChat, which touch on hot-button social and political topics, draw millions of readers. During the pandemic, he frequently criticized Zero-Covid policies and thus drew the ire of censors; over 300 of his articles have been taken down. His Chengdu bookstore Youxing (有杏书店), which opened in 2023, hosts hundreds of events each year and is a rare forum for public debate within China. Last October, authorities ordered it to close, but reversed their decision less than a week later. (Zhang Feng declined to publicly explain why, but hinted at a public or private pressure campaign in a recent post: “Thanks to everyone, including friends whose names I may not know but who were able to make a difference.”)

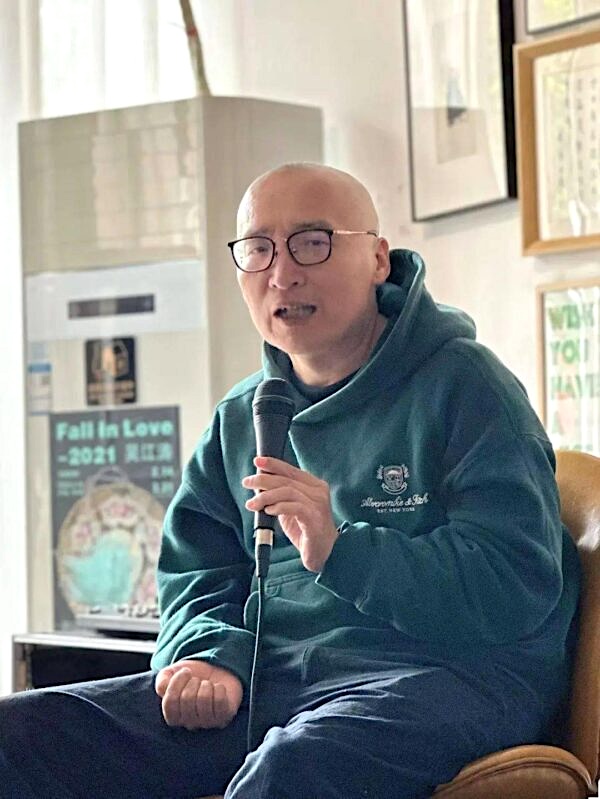

I first met Zhang Feng in New York last summer. He wore black, thin-framed glasses and spoke softly. He seemed quiet, the kind of middle-aged Chinese man who blends easily into the crowd. He reminded me of my father. When he talked about his bookstore and his writing, he became more open, speaking with an easy confidence and a touch of dry humor. We discussed his media career, the space for public debate in China, and his hope that more young people will put their name behind their pen.

Yi Liu: Twenty years ago you started working as an editor and then later as a columnist. Although you’re no longer working in media, you still express your views publicly on WeChat. What prompted you to start writing about current affairs on WeChat?

Zhang Feng: After graduating from the graduate program at Beijing Normal University in 2005, I became a newspaper editor in Chengdu. My public writing began with book reviews, but the publication cycle was very slow — you had to read carefully, maybe for a month, then write a few pieces, and the editor would decide when to run them.

One night I wrote a current-affairs commentary, and the next morning at 9 a.m. the editor published it right away. That was a big encouragement. Later I started writing a 2,000-character [c.1300 word] weekly column on Tencent Dajia [腾讯大家, a publishing platform which shut down in 2020 after allowing critiques of the Wuhan lockdown] which combined current events with deeper analysis, especially on how ideas were changing amid the country’s rapid urbanization.

I wrote fast, the pieces went out quickly, and the impact was large. Soon outlets such as The Beijing News (新京报) and The Paper (澎湃) were commissioning me. From 2016-2019 I was writing commentary almost every day, which trained me to write extremely quickly. I could draft anywhere — in a Chengdu café, a bar, a hotpot restaurant while my friends ate. To me that’s the kind of “real-time” commentary suited to the internet era.

I set up my first WeChat public account at that time, but at the beginning it was limited, because there was no real income — apart from readers’ tips, which brought in maybe 100 or 200 yuan every day [$14-28] — whereas an article for a media outlet could earn 800-1,000 yuan [$110-140], however, this sometimes takes several weeks. I only truly focused on my own account during the Covid pandemic. Not long after the pandemic began, my first account was permanently banned for publishing a piece criticizing how the Party’s power operated at the rural grassroots.

For me, the biggest appeal of writing on WeChat public accounts was the speed. I think I was one of the fastest commentary writers in China. For example, during the pandemic, there was a magnitude 6.1 earthquake in Chengdu. Because of Covid lockdowns, the emergency exits in apartment buildings were sealed, so many people couldn’t get out. I immediately started writing. Within 30 minutes, I had more than 1000 words and published it right away. It took the authorities three or four hours to reach out to me — because bureaucratic systems need time to react — and by the time they contacted me, the piece had already been read more than 300,000 times. Later, the policy was changed: even in areas under lockdown, fire escape routes had to remain open.

Of course, WeChat public accounts aren’t completely free [to publish what you want]. If an article contains certain sensitive keywords, it simply won’t upload. But as a media editor, I know dozens, even hundreds, of these keywords — so I just avoid them.

I feel that whenever something major happens in China, millions, even tens of millions, of people are thinking about, or anxious about, the same thing. WeChat is a logical way to express yourself very quickly. The censorship system usually needs a few hours to catch up, which means that every article has a few hours of life. Yet if you work in mainstream media, those precious hours are consumed by preparation. First they have to hold a meeting to decide how to cover a story, then assign a writer, then the editor revises the draft, then the editor has to submit it to a supervisor for review and so on. That process can take a whole workday — by then the moment has passed, or new censorship directives may have come down. And traditional media outlets now engage in self-censorship as well, so there are many topics they simply don’t dare to move on quickly.

Not long after the pandemic began, my first account was permanently banned for publishing a piece criticizing how the Party’s power operated at the rural grassroots.

You were born in a rural village in Henan and grew up in a period of great change, as China transitioned from the Mao era to the Reform era. How did your upbringing influence your path as a journalist, editor and now a commentator on current affairs?

I grew up in a rural area of Zhoukou, Henan. It was extremely isolated — we didn’t have electricity until 1997 when I went to university. I studied Chinese literature in Qingdao and Beijing, and went through a big shift. In my final year of high school I was a nationalist. I’d read a hugely popular nationalist book at the time, China Can Say No (中国可以说不). That book attacked Wang Xiaobo as a “bourgeois liberalizer” so I assumed he was a bad person. When I later read Wang’s books myself I admired his intelligence, wit and humor — this, I thought, was the higher level.

As a child I’d heard about the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests on the radio, but in the countryside people interpreted it as a power struggle between Deng Xiaoping and other leaders. The radio never mentioned the students’ demands. At university my graduate adviser told me much more about the movement. All of that changed my views.

In the 1990s, when I was in college, some classmates shared DVDs of documentaries about June 4. The content was completely different from the official narrative. But at that time, June 4 was a taboo in my life — not a single teacher ever mentioned it. That was when I started to question things. Later, when I went to Beijing for graduate school, I met my advisor. She had been at the scene during the protests as a student. She told me what actually happened. That was the moment when I woke from my confusion.

June 4 had a deep impact on her. I remember one night around 2002, she called me and asked whether students near my dorm were gathering and shouting slogans. In fact, there was nothing happening that night. She might have been hallucinating — when she was under stress, she would recall the past. People like my teacher suffer because they lived through such momentous historical events. But at the same time, they have what it takes to be free.

That influenced my career choice. I came to feel that being an editor or journalist is an extension of the kind of character she had because this profession demands people who insist on independent judgment and strive to say or write something meaningful. Around 2002, when I was in graduate school, it was still a relatively dynamic time: an era when professors were still willing to express their own views. Now, professors hide themselves. They rarely shape students’ characters because these days expressing one’s own values or political opinions is extremely dangerous.

I remember my advisor once told me, “None of the students in your class were Party members.” But she told me recently that all her students are now Party members. One reason is the job market has become much tougher, and jobs in the system are very cushy. Many students want stable jobs within the system, like civil service or state media, and without Party membership, it’s nearly impossible. Another reason is that after 2008, universities in China changed dramatically. As civil society began to emerge, the Party felt its values were being challenged — intellectuals and students no longer believed in it. After that, universities strengthened ideological control. If you don’t join the Party now, you are pushed to the margins.

In the mass-media era I absorbed ideas of universal values and civil society. Today those concepts are being suppressed. Yet I remain positive. One reason is that far more people have higher education. Another is urbanization: when so many people own homes they want secure property rights. No Chinese homeowner truly thinks a 70-year leasehold is reasonable. Could a return to Mao-era public ownership strip people’s property and send them back to the 1950s and 60s? I think that’s impossible. Mao’s system worked because everyone lived in the countryside and the state could police them there. Now populations are concentrated in cities — 20 million in Chengdu alone — so there’s no going back.

You run several public WeChat accounts and comment quickly on social news, but your articles are constantly deleted by the authorities, and your WeChat account has been shut down. How does the official censorship process work? Can you describe how the police summon you to “drink tea”? How do they decide which pieces to delete, and how do you deal with them?

I’ve noticed that accounts are usually shut down for three reasons. First, if you mention China’s top leaders. Second, if you criticize the fundamentals of the Party system. Third, if you attack the Party’s historical narratives. In these cases, once your account is banned, there is no way to get it back. It’s said that even some retired deputy editors from People’s Daily (人民日报) had their accounts shut down for writing such pieces.

For example, my first account that was shut down was called “Observations on Middle-Class Life” (中产生活观察). I registered it in 2014, but I rarely posted on it before 2019. Then, in August 2021, I published a commentary about a murder case involving a farmer in Fujian, which touched on how the Party exercises power at the grassroots level in rural areas. The account was permanently banned after that. Since this touches on Party ideology, it falls under the jurisdiction of the Cyberspace Administration of China (中央网络安全和信息化委员会办公室), so it was removed by them without contacting me directly — they probably didn’t even know who I was.

My other WeChat account was deleted because I once wrote, “My father didn’t like Mao Zedong; he liked Deng Xiaoping.” That article couldn’t be posted. I tried deleting the sentence, and in the middle of editing it my account itself was removed.

[Sometimes] an article is published, but goes viral and triggers manual review. My pieces usually pass the first machine review, but if their reach is big enough they go to a second review. I’m not sure how many readers would trigger this kind of scrutiny, but I have a feeling that 100,000 views [the maximum number of views a WeChat article can display, even if the actual view count is higher] might be a key threshold. Many of my pieces were censored after reaching that number. In such cases, sometimes officials would reach out to my friends and ask them to tell me to take the article down; other times, they contacted me directly.

I’ve met many state-security officers and police. None of them sincerely believe that democracy is bad or dictatorship is good. At most they say China must be stable first.

From 2015 to today, some 300 of your WeChat articles have been deleted, yet you keep writing. Why?

Because of human nature. I can sense that the public supports me; this gives me a certain amount of influence. I’ve also found some ways to reduce the risk of drawing local official attention. In every critical piece, about a third of the text expresses my affection for Chengdu. For example, during the pandemic, Huaxi Hospital shut down after a Covid-positive patient was detected. I wrote that this hospital is a source of faith and resilience for people. For an institution like that to suspend operations because of a single positive case was something that should never have happened. The essay went viral, and it moved many doctors. Hospitals are meant to treat patients, they thought — so they shared the essay like crazy.

If you point out a problem without naming who should be sacked, there’s less trouble — they may think I’m writing for the good of the city. During the pandemic I also saw a special phenomenon: when one place imposed controls, its local media wrote nothing, but media from elsewhere sometimes did. That’s a form of power balance — officials compete with each other. If something goes wrong in Beijing, officials in Sichuan may feel that it makes their own performance look better by comparison. So when I comment on current events happening elsewhere, it may not attract the attention of the authorities in Chengdu.

I’ve met many state-security officers and police. None of them sincerely believe that democracy is bad or dictatorship is good. At most they say China must be stable first, democracy might bring chaos. If China changed overnight, like the Soviet Union, I don’t think they’d point guns at me.

Do you think your articles actually change reality? How can you tell?

If you don’t attack the entire system but focus on concrete facts, it works. After my first WeChat account was banned I launched a second one. Early on, a piece about Zhang Wenhong [张文宏, a Chinese infectious disease expert who became one of the most widely trusted voices in China during the pandemic] got 2.7 million views. I noticed that when there was a local outbreak in Chengdu, writing about it had a great impact. During the pandemic my pieces had real effects nationwide.

The first time I felt this power was in a story about a couple in Chengdu who had Covid and owned three cats. The authorities killed their cats. I have a dog and was furious, but saw no local media report it. I immediately wrote a critical article. It went viral. After the authorities contacted me, I deleted the article within 24 hours. By then, it had nearly 200,000 views. That night, the head of the local internet police (网信办主任) phoned me through a former colleague asking to meet. The next day, we met in Starbucks. I asked if he had pets; he said he had a dog. I told him: As a dog owner don’t you think this action is despicable and wrong? He admitted it was. I said I’d heard maybe 100 people were planning to drive with their pets to protest — actually I invented that, I only knew many were angry. He was terrified and asked me to delete the piece. I said I would if I could post another article saying Chengdu had no plan to cull animals, that the district had acted wrongly, and that they promised not to harm animals again. He agreed. I deleted the first article and posted “A Better Way to Treat Pets.” After that there were no more pet killings. That was my first sense that WeChat writing can make a difference.

In November 2022, as part of the Zero-Covid policy, several high-rise apartment buildings in Urumqi had their fire exits blocked as “pandemic control measures.” A fire broke out in one, and ten people died. Two months earlier, Chengdu had implemented similar policies. The fire exits in the residential compound where my friend lived were also blocked. When I learned about it, I wrote an article titled “Chengdu, Please Open All the Fire Exits.”

The piece spread very quickly. Within four hours, government officials reached out to me through various intermediaries asking me to delete it. I took it down, but that same evening, the Chengdu authorities issued a new policy requiring all residential compounds to reopen their fire exits. Even if there were positive Covid cases in a building, volunteers should be assigned to manage the doors instead of sealing them.

You follow WeChat public accounts, independent bookstores and new forms of publishing. Compared with the past, how active — or dead — is public debate in China today?

It’s active but completely fragmented. Although controls feel strict, every major public incident now generates lots of expression — that’s the double edge of technology. Big platforms like Tencent Dajia have been shut, large WeChat accounts have been banned — that’s the harsh control we can see. Yet on the night Dr. Li Wenliang [the Wuhan doctor who sounded the first alarm about Covid] died — perhaps the strictest level of control since China went online — maybe a million people were writing at once. The government activated an emergency plan and blacklisted keywords.

In the end, Arabic script, reversed symbols and gibberish appeared as people found ways to express themselves. Most content was still deleted, but I think such expression awakens the public. Overall expression is scattered and individual. Many high-quality, influential accounts are gone, but countless ordinary people — previously not writers — are posting views. So I’m not pessimistic. Is there really anything in China today that cannot spread at all? Take the Peng Zaizhou incident [in 2022 Peng hung a protest banner on a Beijing bridge]: even with massive deletions online, many people in Chengdu knew about it.

But inside China’s internet, much information is unsearchable. Do these fragmented debates still have value?

The information is scattered and chaotic, small-scale. That only proves that speech police cannot kill it 100%. But logical, valuable, in-depth expression is still absent. Sometimes this produces tons of fake news: anything unfavorable to the Communist Party spreads wildly. On Twitter there’s a huge appetite for fabricated China stories, saying the top leader is about to die and so on. It’s absurd, but the demand is large. That’s sad.

In the mass-media era I absorbed ideas of universal values and civil society. Today those concepts are being suppressed.

There are so many stories about China! But many Westerners think all Chinese people are the same. For example, that they’re all controlled by the Communist Party and share the same ideology. What would you like to say to these Westerners?

I think this is the effect of the Great Firewall. An American scholar once told me that as a scholar studying China, it has become increasingly difficult for him to enter the country; the sources he can access are getting fewer and fewer; he has very little to rely on. Because of the firewall, neither side can see the other’s moves.

But new phenomena are emerging. For example, there are independent bloggers in China who have not been educated in Party schools and are not paid by the government; they have to survive on the market and live off their readers.

During the pandemic I discovered that, in Chengdu, I knew more about the city than any local official, and many people there also knew me. I feel a genuine sense of support in Chengdu. During the pandemic, I wrote articles opposing blanket restaurant closures, and some restaurant owners told me I could eat there for free forever. These restaurant owners don’t completely share my views, but at the same time they know lockdowns inevitably hurt the economy, so they support my stance. I’m often recognized on the subway as well.

Among my WeChat pieces, the most-read one reached six million views. I believe I represent the voices of many. I think this is the new media era. This leaves me without any fear. I know many Chinese journalists overseas often feel afraid, but after so much contact with local police stations, propaganda departments and state security, I understand how they think, which gives me some confidence. So in Chengdu I’ve never worried about being arrested myself.

This is what I hope to convey to Western readers: there is still so much happening in China, and many ideas and debates are constantly taking shape. China is not a monolith.

How did you come to start your bookstore, and how is business doing these days?

In the spring of 2023, when Chengdu finally lifted all its pandemic restrictions, two friends came to me and said they wanted to open a bookstore with me. We were sitting under an apricot tree drinking tea, so we decided to name it Youxing — literally, “With Apricots Bookstore” (有杏书店).

I didn’t invest much money in the store. Because my friends manage a cultural and creative complex, getting the business license was easy; the administrative and accounting support was already there. The bookstore officially opened in August 2023. In fact, during the pandemic, Chengdu experienced a small wave of independent bookstores. I think that was because for those three years, many government departments were focused on epidemic control, with staff reassigned to public health work, so oversight over independent bookstores loosened somewhat.

Over the past two years, our bookstore has hosted around 200 events annually — debates, author talks, classical music listening sessions and so on. After the assasination attempt on Trump, we held a debate titled “What Does ‘One-Click Deletion’ Mean For Our Politics?” (一键删除在当代政治有意义吗?) The topic sounded oblique, but it was essentially about whether assassination attempts truly help society. Soon after, the local police came to ask what the event was about. We explained that it was a discussion of the U.S. president being shot, and they said, “No problem.”

Chengdu has over 3,000 bookstores — second only to Beijing. Why do you think Chengdu has such an unusually vibrant bookstore culture, and what makes the city so unique in its cultural atmosphere?

Personally, I find Chengdu special because it feels far from Beijing. People here don’t treat politics from Beijing as the most important part of their lives. For example, when I meet young people in Chengdu, few of them view civil servants as a top choice when looking for a partner.

I also think the current anti-corruption campaign has created a sense of nihilism among officials. Across many sectors, officials feel that the more they do, the more mistakes they risk making — so why bother? As a result, when they come across tasks that aren’t absolutely required, they may simply let them slide and go home when their workday ends.This tendency may be even more pronounced in cities farther from the political center in Beijing.

During the pandemic I wrote about the collapse of Chengdu’s mass-testing system. The head of Chenghua district, where I live, phoned me asking to meet. I refused — I only had one hour outside per day and I said I’d use it for running. Then the propaganda chief and district head came to my home. I felt the Chengdu authorities weren’t barbaric. They said they just wanted to communicate, and were almost embarrassed to say “delete.” I told them I’d take the article down, but if something bad happened in Chengdu I’d keep writing.

The local police came to ask what the event was about. We explained that it was a discussion of the U.S. president being shot, and they said, “No problem.”

Over the past 20 years, what changes have you observed in China’s media and self-media?

Institutional media in China today has essentially lost all influence. Independent content creators — the so-called self-media (自媒体) — still have some reach, but it’s limited. China simply doesn’t allow self-media to grow into major public opinion leaders.

Many self-media accounts are influential in their own niche. For example, the writer “Liu Shen Leilei Reads Jin Yong” [六神磊磊读金庸, a popular WeChat account that comments on Jin Yong’s martial-arts novels in a witty, accessible way] often gets hundreds of thousands of views. Its readership routinely surpasses even the most well-known media outlet’s WeChat accounts in China, including Southern Weekly’s (南方周末). But these creators cannot become institutionalized. They can only talk about topics like literature; once they touch on anything “sensitive,” their accounts are shut down immediately. For instance, if a self-media writer wants to investigate a social incident, they would need official reporting credentials to conduct interviews legally, which are issued by the National Press and Publication Administration (国家新闻出版署), and the lack of them can restrict your ability to report or write freely.

Could you talk about how platforms for public opinion in China have shifted over the years, from traditional media, to Weibo, to WeChat, and now perhaps to Red Note?

Essentially, quality content — such as in-depth articles from newspapers and magazines — has become increasingly scarce in the era of WeChat official accounts.

| ZHANG FENG’S RECOMMENDATIONS | |

|---|---|

| CHINESE BOOK: | Salt Town (盐镇) by Yi Xiaohe |

| ENGLISH BOOK: | Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin by Kei Hiruta |

| WECHAT PUBLIC ACCOUNT: | Sanlian Life Weekly (三联生活周刊) |

| TRADITIONAL MEDIA: | Southern Weekly (南方周末) |

One reason is that truly excellent content remains scarce and relatively elite. For instance, deeply researched writing from outlets like Sanlian Life Weekly (三联生活周刊), Southern Weekly (南方周末), Portrait (人物) and Face-to-Face Connection (正面连接) have a high quality and significant influence, yet they are only four publications. In today’s new media landscape, with millions of public accounts vying for attention, readers no longer hold a single publication like Southern Weekly in such high regard. My own account sometimes garners more views than the entire commentary section of Beijing News.

Furthermore, the rise of platforms like Douyin [抖音, the original Chinese version of Tiktok] and Xiaohongshu [小红书, literally “Little Red Book” but rebranded in English as Red Note] has fragmented attention even further. A reporter recently told me that no one on Xiaohongshu likes journalists — which is deeply saddening. Whenever a blogger on Xiaohongshu mentions a journalist, the attitude is invariably negative, viewing journalists as figures to be guarded against, who come to dig up news and pry into others’ lives. The core value of Xiaohongshu is recommending which restaurants are delicious, which shops are stylish.

During the Weibo era, people trusted journalists, and would send them private messages with news sources. Now the public opinion platforms are completely fragmented — WeChat official accounts, WeChat [private] groups, and so on. Especially in WeChat groups, people share screenshots of all kinds of articles without knowing who wrote them. Compared to traditional media, I feel the quality of these articles has declined because much of it can’t be verified.

In this new media era, how can someone still be a truth-telling creator on the Chinese internet?

I hope young people become more willing to put their names to their public statements.

In the past, journalists felt a sense of honor in having their names attached to their work — people valued their bylines. But now, regardless of whether the topic is politically sensitive, even when it’s just poetry with no connection to politics, young people still prefer not to sign their names. That reluctance comes entirely from fear. Today’s environment discourages people from taking responsibility, and I think this trend not only makes everyone less accountable in the public sphere but also deepens the very fear they’re trying to avoid. Because in the end, the authorities can find you whether or not you sign your name — and this is precisely how fear is manufactured.

How is your dog now, did she survive Covid OK?

My dog passed away very suddenly in 2024 due to organ failure. She lived for 13 years and even made it through the pandemic, but then she left without warning. It was a heavy emotional blow. I don’t think I’ll be able to have another dog again. ∎

Yi Liu is a bilingual journalist from Chongqing, based in New York. She previously worked at The Wire China, The New York Times and The Beijing News. Her articles have also appeared in The China Project, Initium Media and other outlets.