Reviewed:

• China’s Hidden Century, ed. Jessica Harrison-Hall, Julia Lovell (University of Washington Press, 2023)

• Creators of Modern China, ed. Jessica Harrison-Hall, Julia Lovell (Thames & Hudson, 2023)

At the end of a shadeless square in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, the rusted wings of the Xinhai Revolution Museum beckon visitors into a series of vast exhibition halls that tell the story of China’s long 19th century.

As the museum display informs the visitor, the Xinhai Revolution began in Wuhan in 1911, and eventually “overthrew the Qing Court’s ruling, which ended the absolute monarchy for more than 2,000 years.” The English translation of the exhibit’s introduction outlines the Party-endorsed story of the imperial decline and foreign aggression which gave birth to the people’s revolution:

“Since the mid-19th century, imperialistic powers intensified their invasion of China and they forced Qing government to sign a series of unfair treaties[…] China was partitioned by the invasive powers of fierce loot. The Qing dynasty was declining among social turmoil and bitterness of its subjects.”

This narrative is reflected by the structure of the museum halls:

Exhibit 1: National Crisis were deepened and social conflict were intensified

Exhibit 2: Explore the ways of saving the country

The Chinese Communist Party was not founded until 10 years after the Xinhai Revolution, but the national humiliations of the 19th century have become a crucial part of its creation myth. The Party’s 2021 Historical Resolution declares: “The country endured intense humiliation, the people were subjected to untold misery, and the Chinese civilization was plunged into darkness. The Chinese nation suffered greater ravages than ever before.”

“To save the nation from peril,” it goes on, “the Chinese people rose to fight back, and patriots of high ideals sought to pull the nation together, putting up a heroic and moving struggle.” The disparate uprisings and social movements of the era — the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64), which resulted in the deadliest civil war in history; the failed Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898; the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 — are all presented as failed attempts at national renewal. In this skewed version of 19th history, they are merely precursors to the Chinese Communist Party taking power in 1949, and ending what in China is dubbed the “century of humiliation.” To deviate from this state-sanctioned account is to engage in what Xi Jinping has termed “historical nihilism.”

The question of who gets to tell the story of China’s tumultuous 19th century has never been more fraught

In English-language scholarship, accounts of China’s 19th century have not been distorted by such propaganda, but have been partial in their own way. Anglophone histories (Stephen Platt’s Imperial Twilight; Robert Bickers’ The Scramble for China) tend to focus on the two Opium Wars (1839-42 and 1856-60) between Britain and China, and other moments of foreign aggression, foregrounding exploitative political and economic instincts that grew as the Qing dynasty weakened. Primary sources for such studies have often been drawn from those administering, living in or trading from China’s coastal and river cities which became treaty ports, and have foregrounded voices of the British government and East India Company, the Chinese court and bureaucracy, and both militaries.

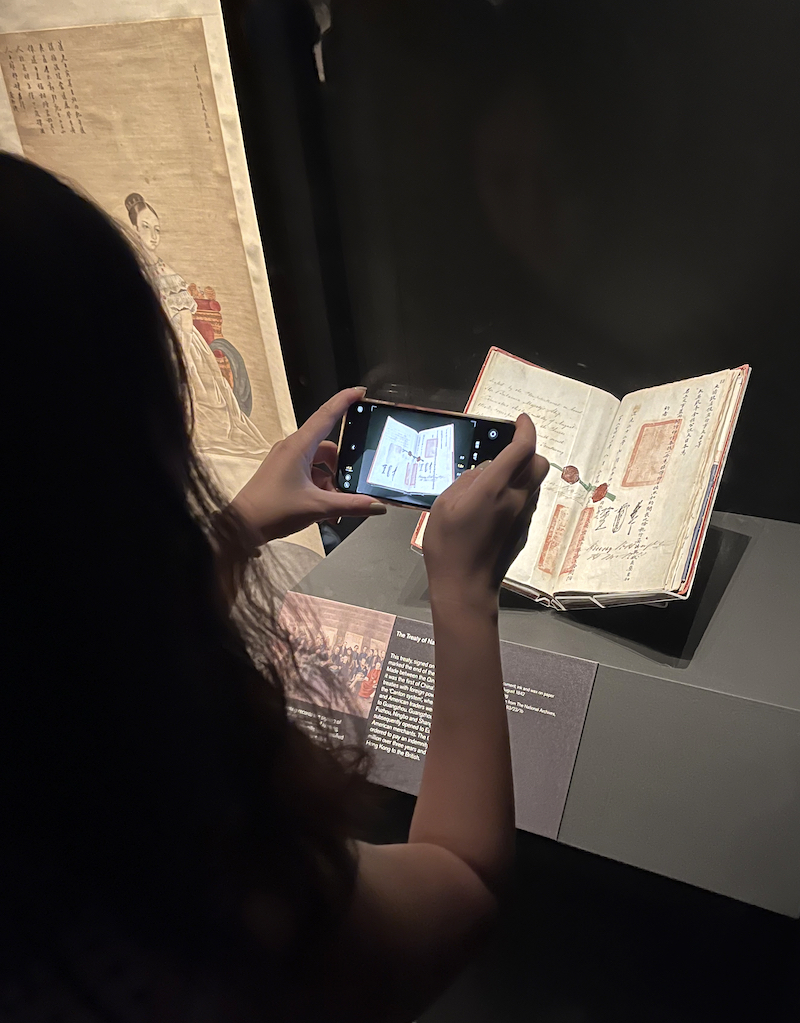

China’s Hidden Century — the title of both the British Museum’s recent high-profile exhibition and the lavish accompanying book under consideration here — does not attempt a revisionist approach to the 19th century. Instead, it presents a range of objects and artworks which illuminate the diversity of lived experience during that era. We have plentiful acknowledgment of foreign aggression, including Friedrich Wilhelm Keyl’s portrait of Looty, the first Pekingese dog to come to Britain (found wandering the grounds of the Summer Palace in Beijing when British forces looted it during a punitive expedition in 1860, presented to Queen Victoria as a gift, and so named — somewhat baldly — by the Queen herself). There is also the original Treaty of Nanjing, around which a queue of Chinese visitors regularly formed at the exhibition.

But we also have remarkable artifacts of material culture, such as a child’s hat in the form of a fish dragon, replete with horns and bulging eyes, made by a skillful mother for her son. Or a coat made of thick palm-fiber, two triangles of bound thatch like miniature cottage roofs, to keep the rain off a farmer. One aristocratic scarlet jacket looks unexceptional until you notice the pattern of its border, which incorporates images of British steamships, which traveled up and down China’s coasts and rivers to the treaty ports they had forced open. “Urban fashion thrived on novelty patterns,” the accompanying note observes, “created from a pool of imagery that included popular prints [and] advertisements.”

The book, edited by the exhibition’s curators Julia Lovell and Jessica Harrison-Hall, responds to the era not chronologically, but by looking at six topics: the court; the military; elite art; vernacular culture; global Qing; and “reform to revolution.” Each is explored in essays by historians of the period, and in her foreword Lovell poses some of the broad questions that the book interrogates:

“What happens when central control and legitimacy break down and people can no longer rely on traditional leaders? Why and how do migrant communities drive creativity that in turn defines a city? How do new patterns of work and technologies transform everyday life? And […] how can a society riddled with inequalities continue to function?’

It is a substantial tome: a coffee-table book that incorporates many more objects and artworks than the actual exhibition could fit. The substantive research work that went into the exhibition has also produced a hardback volume titled Creators of Modern China, a collection of short accounts, written by a team of international scholars, of the lives of one hundred men and women “whose contributions to the 19th century helped lay the foundations of modern China” — including figures entirely new to this reader, such as female pirate chief Shi Yang and proto-feminist poet Shan Shili.

Both books are scholarly, illuminating and lavishly illustrated, and do a good job at enriching and complicating narratives of the 19th century. Indeed, the chief complaint one could level at them (if it counts) is that they are too weighty to allow for the extended scrutiny they deserve here. However, the exhibition itself generated controversy due to to the initial omission (since rectified) of a credit to the translator Yilin Wang, whose work had been used in a final section dealing with the revolutionary and feminist writer Qiu Jin.

On social media, debate raged about who gets to unpack China’s history, with frequent reference to the British Museum’s historical theft of cultural artifacts. (Most of the items in this exhibition were on loan from other collections, and the book draws on a huge range of museum holdings for its images, including The Palace Museum in Beijing.) Online discussions also questioned whether it was even appropriate to try to represent the 19th century in a more diverse way; should not the focus remain solely on the aggression of foreign powers, and the terrible human suffering of the era?

snap of the Treaty of Nanjing (Alec Ash)

In China, a recent editorial in the nationalist newspaper Global Times called for the return of the British Museum’s thousands of Chinese artifacts. Meanwhile, a short video series about a teapot from the collection which takes human form and attempts to return to China, titled Escape from the British Museum, has been viewed hundreds of millions of times. State television commented on the viral videos: “We are very pleased to see Chinese young people are passionate about history and tradition … We are also looking forward to the early return of Chinese artifacts that have been displaced overseas.”

The question of who gets to tell the story of China’s tumultuous 19th century — and of what that history should focus on — has never been more fraught. Yet, even as more than one new museum opens each day in China, the official narrative of its modern history is ever more tightly-controlled within the nation. Diversity of approach and perspective, and the debate it provokes in contexts where free speech is permitted, is surely a welcome antidote to the Party’s own totalizing approach to China’s past. ∎

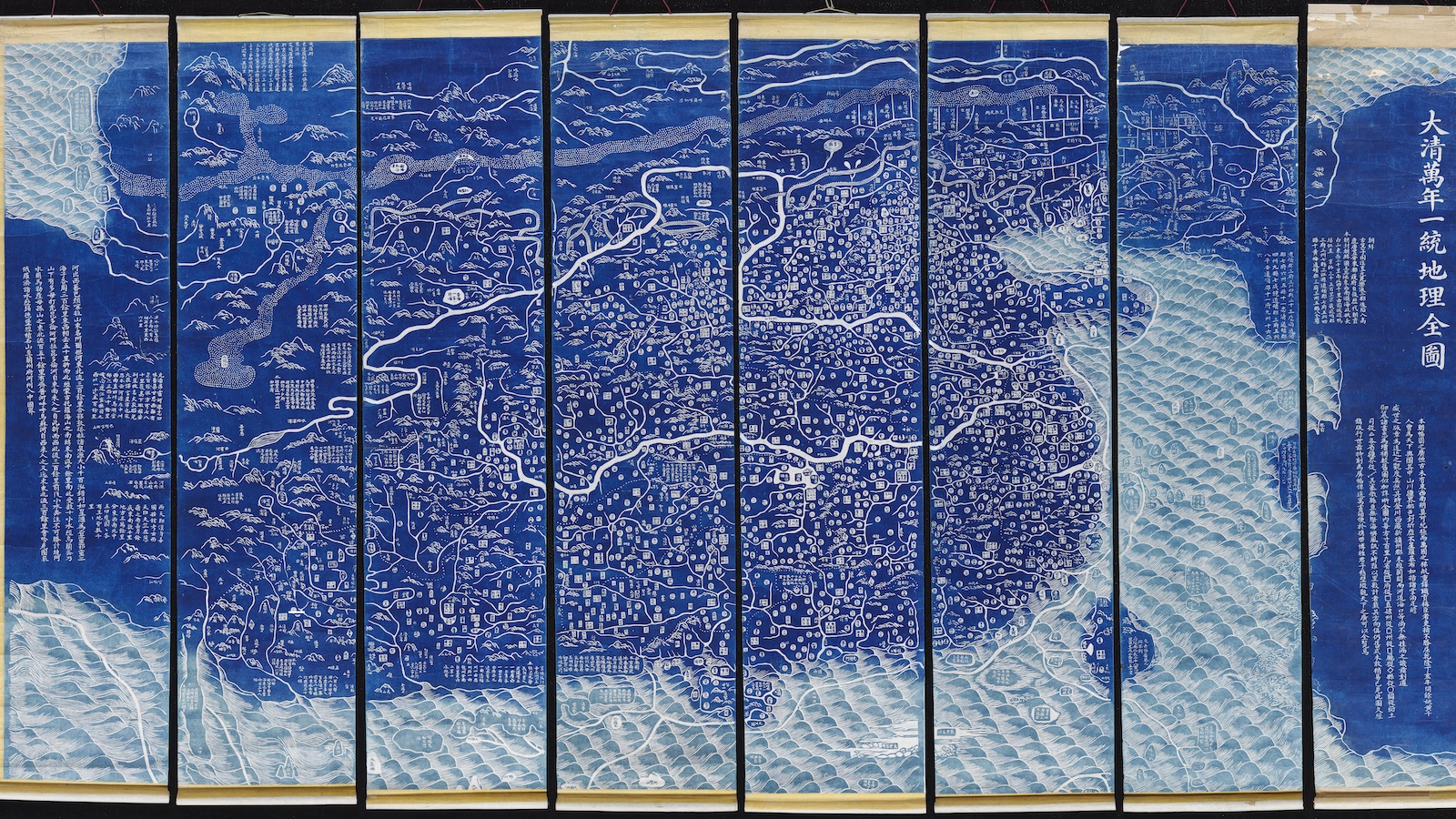

Header: “Complete Map of All Under Heaven Unified by the Great Qing” (China, c.1800), exhibited in “China’s Hidden Century”. © The British Library

Jonathan Chatwin is a writer and teacher focused on China. He is the author of Long Peace Street (2019), tracing the history of a single street in Beijing, and The Southern Tour (2024), an account of Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 tour of southern China to boost the nation’s private economy.