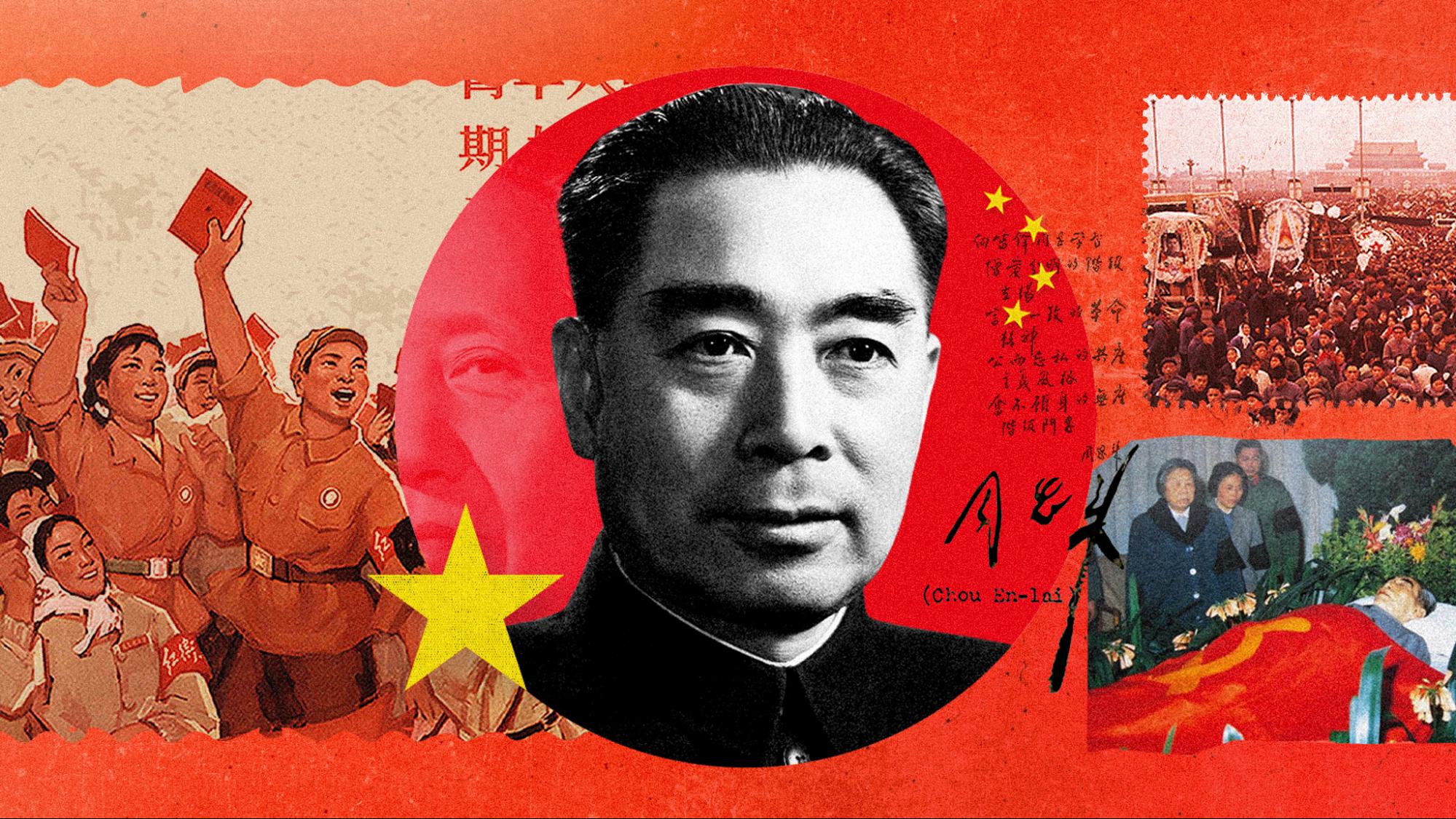

Reviewed: Zhou Enlai: A Life, Chen Jian (Harvard University Press, 2024)

Hospitalized in the summer of 1975, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai was dying of cancer. Intrigue swirled through the halls of power. Chairman Mao Zedong — also seriously ill from ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease — updated texts he had written decades earlier, criticizing the Premier for arcane ideological disagreements. Zhou was desperate to fend off the rivals circling his deathbed, including Mao’s vituperative wife, Jiang Qing. On June 16, Zhou wrote Mao a groveling letter:

Despite the Chairman’s endless teaching, I have still repeatedly made mistakes or even committed crimes. … About all this, I feel tremendous shame and regret. Now, in my illness, I have repeatedly recalled those mistakes.

Chillingly, Zhou flattered and lavished gratitude onto Mao, even though the Chairman had ordered doctors to withhold surgery from Zhou — treatment which may have prolonged the life of the Premier, who was Mao’s second-in-command.

Mao and Zhou consulted with and depended on each other, but also secretly plotted and fretted over who would die first. The ultimate survivor hoped to shape the historical “verdict” on the other, defining a complex dynamic which was a key factor in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s existential struggles. Zhou so feared being criticized by Mao that he was embarrassingly sycophantic. His letter presented Mao with a self-critical summary of his career, but before he could complete it Zhou died, on January 8, 1976, at the age of 77. Eight months later, Mao too passed away, plunging China into a dramatic power struggle in which reformist Deng Xiaoping emerged the winner, leading China onto the path of economic modernization.

Succession, the Achilles’ heel of Zhou and Mao’s relationship, is once again on people’s minds in China (if not their lips). Many Chinese yearn for another “good Premier,” a phrase many Chinese used to refer to Zhou. Yet someone who might fulfill this hope today remains nowhere to be seen. The current Premier, Li Qiang, assumed the post last year, and so far is known best for his deference to General Secretary Xi Jinping. His recent predecessors would, at times, speak to champion the poor and marginalized. But Li has fewer chances to speak at all. Last March, the Premier’s annual press conference — normally the climax of each session of the National People’s Congress, or parliament, since the 1980s — was abruptly cancelled until further notice.

Not long ago, Beijing almost had someone like a “good Premier.” Li Qiang’s predecessor, Li Keqiang, was popular, though eclipsed by Xi and bureaucratically weak. His fans nursed secret hopes that he would emerge from his boss’s shadow. Those hopes collapsed when Li Keqiang retired in March 2023. In October last year, he died unexpectedly. Officially, the cause was a heart attack while Li was swimming, yet skepticism abounds. An “underground” digital-only document circulated in cyberspace, citing “abnormal circumstances” around Li’s death. “Why was Li sent to a traditional Chinese medicine hospital instead of an emergency room that was closer by?” said one Chinese source who requested anonymity as he showed it to me on his electronic device. It’s title is simply Him (他).

Many Chinese still remember Zhou as the original “good Premier.” They credit him with shielding thousands of victims from persecution, or worse, during the Cultural Revolution, when ultra-leftist extremists held sway. Half a century after he died, beatific imagery of Zhou is still hard to escape. Tour guides at palaces and museums explain that he protected cultural relics from destruction by rampaging Red Guards. In sprawling flea-markets, his iconography is almost as omnipresent as Mao’s. Yet middle-class Chinese admit they’re ambivalent. “Zhou’s reputation has been tarnished in recent years, especially among intellectuals,” one Chinese member of the intelligentsia told me. “I confess that I cried when Zhou died. He was the one who had given us hope.”

For decades, Zhou has been perceived as the CCP’s compassionate empath, scrambling to contain the excesses of his paranoid, abusive boss.

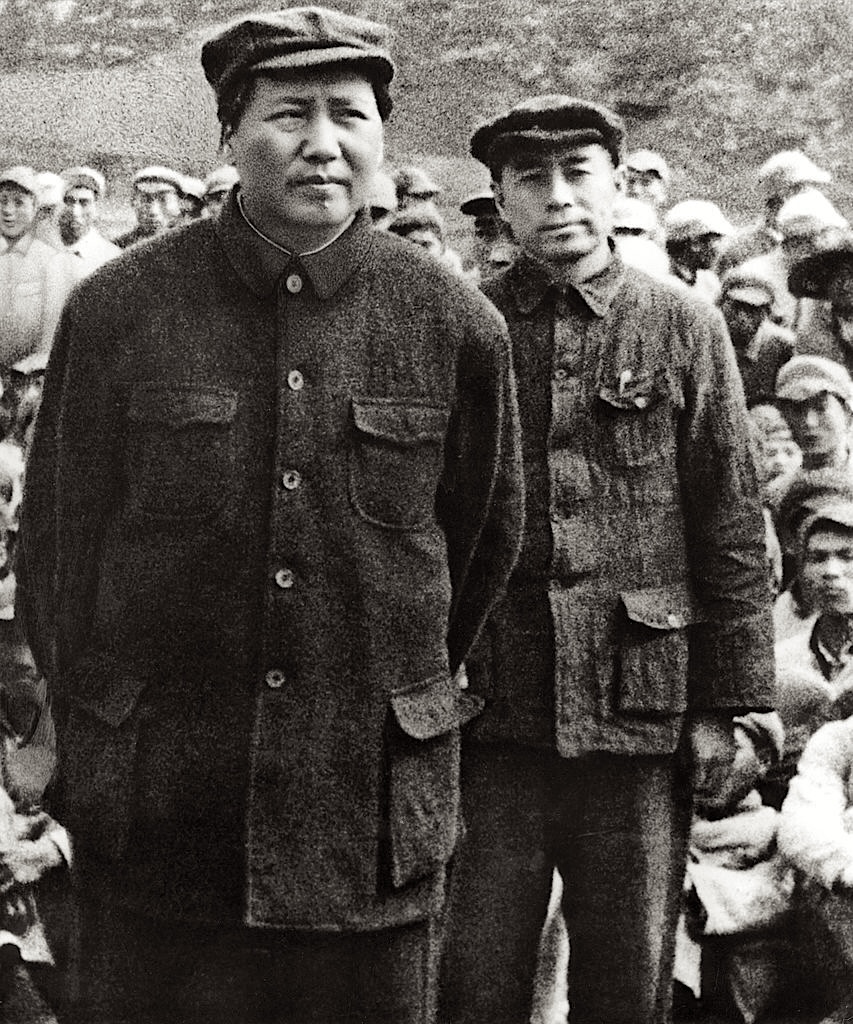

The paradox of Zhao’s relationship with Mao is on full display in Chen Jian’s impressive biography Zhou Enlai: A Life (Harvard University Press, 2024). For decades, Zhou has been perceived as the CCP’s compassionate empath, scrambling to contain the excesses of his paranoid, abusive boss. Mao had the leadership skills and killer instinct, but needed Zhou’s organizational talent and attention to detail. Zhou could mesmerize guests at a dinner party. But it was Mao’s fiery rhetoric and “animal magnetism” — as the late US president Richard Nixon put it — that drew cheers and tears from thousands in Tiananmen Square as they gathered to honor their leader. This co-dependence wasn’t just a magnetic pull between opposites. It was symbiotic: the yin of Zhou required the yang of Mao — or so Zhou seemed to think. The two were locked in a perpetual cycle of mutual admiration, suspicion and need.

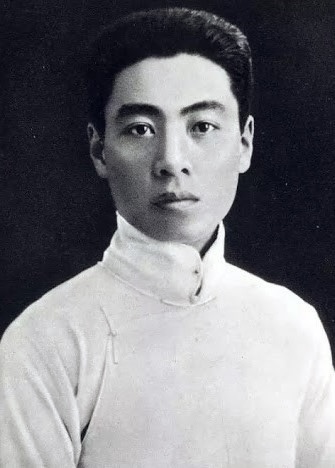

Foreign perceptions of Zhou can veer into hagiography. He is seen as the consummate diplomat whose charm, good looks and people skills lead him to stunning achievements, such as the Sino-US rapprochement of the 1970s. Henry Kissinger famously described Zhou as “one of the two or three most impressive men I have ever met,” while former U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld said Zhou possessed “the most superior brain I have so far met in the field of foreign policy,” according to The China Diary of George H. W. Bush (2008). Zhou was “the only really good man we’d met in China,” said journalist Martha Gellhorn after she and her husband Ernest Hemingway secretly met him in 1941. (Revealingly, Hemingway saw Zhou as slippery.)

Chen Jian’s strong suit is Chinese-language material, including his own interviews, and the book is a prodigiously researched narrative. It is difficult to imagine a more comprehensive chronology of what Zhou did, when and with whom. Chen steers clear of speculating much about “why?”; those motivations, he writes, were locked inside Zhou’s “innermost world.” Nonetheless, the book mentions several factors which may have influenced Zhou’s actions. With a historian’s care, Chen poses these as questions, not declarations, and invites us to draw our own conclusions.

Exploring Zhou’s dark side is like a criminal investigation, with the sordid corners of China’s political landscape as the crime scene, and Zhou increasingly seen as a suspect. How big was the conspiracy? Given the symbiosis between Zhou and Mao, who was the real mastermind? As Chen reminds us, some key documents remain classified. Others are said to be lost, including hundreds of letters Zhou exchanged with his wife. Chen himself, loath to be judge and jury, claims there are “no definitive answers on how Zhou’s position in history would be illustrated and defined.”

For those yearning to peek into that “innermost world,” however, Chen offers some insight. Zhou had once been Mao’s superior in the early communist cause, but a series of events — some relatively small, such as a bold battlefield decision that paid off for Mao — persuaded Zhou that the leader of China’s revolution needed the cutthroat ambition which Mao displayed. By increments, Zhou began to support and defer to Mao. Chen writes that Zhou was “more a man of action than of ideas,” lacking Mao’s “utopian idealism and charisma,” summarizing:

What differentiated Zhou and Mao was not Zhou’s absence of ideas or vision, but his lack of the requisite will and determination to rise to and maintain the position of the revolution’s supreme leader.

Their symbiotic relationship ultimately led to tragedy. Mao became ever more destructive, and Zhou was unable to break free from his evil twin. Zhou seemed obsessed with not being named Mao’s official heir apparent, because so many had met painful fates. His obsequiousness seeped into mainstream consciousness after a Chinese-language book, Zhou Enlai’s Later Years (晚年周恩来) by Gao Wenqian, was published in the 1990s and later translated into English. It was banned on the mainland, but Chen credits Gao with complicating public perceptions of Zhou inside China that used to be two-dimensionally positive.

Perhaps most disturbing was Zhou’s acquiescence to the arrest of his adopted daughter, the actress Sun Weishi, during the Cultural Revolution, when Mao’s wife Jiang Qing brought “evidence” of Sun’s wrongdoing (supposedly “counter-revolutionary activities” and spying for the Soviet Union) to Zhou, and compelled him to sign the arrest warrant. Sun was imprisoned in March 1968, and died in October of that year. “Did she commit suicide or was she murdered?” wrote Zhou when he was informed of the news. Sun’s remains were cremated before an autopsy could be performed to confirm an answer. When Zhou’s wife heard this, writes Chen, she “burst into a loud sob, lamenting ‘How miserably has she died!’”

Why did Zhou continue to flatter and fawn over Mao, while humiliating himself again and again? The American-Chinese media personality Hung Huang — who had met Zhou in the 1970s as a child (“he pinched my cheeks”) as her mother was Mao’s English tutor — told me that after she read Zhou Enlai’s Later Years, she concluded that “Zhou’s tone sounded like that of a petrified mouse in front of a cat. It’s clear he was motivated by fear.”

The yin of Zhou required the yang of Mao. The two were locked in a perpetual cycle of mutual admiration, suspicion and need.

Zhou was born in 1898 in Huai’an, a modest town in Jiangsu province. His family were once prominent mandarins, but its fortunes had been declining for about 600 years. His father Zhou Yineng, according to Chen, had “no outstanding talent or ambition to speak of, and [was] burdened by a personality that was by no means strong or aggressive,” holding low-paying jobs all his life. Instead, Zhou Enlai’s authority figures growing up were women — first his mother, and later his aunt Madame Chen. The latter was a formidable woman who began teaching Zhou to write Chinese when he was four, and oversaw his learning of Chinese literary classics and Confucian ethics.

When Zhou was nine, both his mother and Madame Chen died. With his father working in a distant province, Zhou became the man of the family in a debt-ridden household. Zhou later recalled how “humiliating” it was when he visited pawn shops for cash to buy urgent family items, according to Chen. These experiences, Chen argues, taught Zhou to be tolerant, resilient and tough — and also “sowed the seed of his unwillingness, as well as inability, to claim a top leadership role in the Chinese communist Revolution.”

In 1910, Zhou travelled out of Jiangsu to live with an uncle, Zhou Yigeng, in Manchuria. There, in addition to traditional Chinese classes, he was exposed to math, English, physics and geography. He learned about the then-radical idea of a nationalist revolution to save China and throw off Manchu rule, awakening a “raw patriotic sentiment” in Zhou, Chen writes. The region had been ravaged by a war between China and Japan in 1895, and another between Russia and Japan in 1905. When the Xinhai Revolution toppled China’s Manchu-led Qing dynasty in October 1911, 13-year-old Zhou was the first in his school to cut off his long pigtail or queue, a symbol of Chinese loyalty to the Qing. Chen asks: “Did this act foreshadow Zhou’s interest in politics and his inclination, though still vague, toward revolutionary change?”

In 1913, Zhou moved with his uncle to the treaty port of Tianjin, where he studied at the Nankai School. An avid reader of newspapers and western books, he also led a student theatrical organization, and played the female heroine in the drama One Dollar (一元钱). This prompts Chen to investigate the long-standing rumor that Zhou was homosexual, but he finds “no direct evidence” to support it. (Zhou’s sexuality has been a hot topic for decades. In 2016 Tsoi Wing-Min wrote a book, The Secret Emotional Life of Zhou Enlai, about her theory that Zhou was a gay politician born a century too soon. She suggested he was especially close to a male schoolmate, Li Fujing, but lacked authoritative evidence of a sexual relationship.)

There is no question, however, that Zhou’s commitment to communism became more important to him than sex, marriage, prestige or possibly even family. He practiced celibacy for a time, then in 1925 he married Deng Yingchao, a revolutionary activist in her own right. Between revolution and love, Chen writes, they agreed that “the former must always precede the latter.” When Deng made a boat journey to meet Zhou in Guangzhou to get married, he was too busy to meet her at the dock; she made her way to his quarters on her own.

Chen investigates the long-standing rumor that Zhou was homosexual, but he finds “no direct evidence” to support it.

Chen traces the origin of Zhou’s politicization to 1915, when Japan imposed its notorious 21 Demands on China during World War I, claiming spheres of influence and installing Japanese advisors in the Chinese government. In an essay which he presented to teachers and students, Zhou warned that his country approached an “urgent moment of a life-and-death challenge,” adding: “My emotion of patriotism has reached the boiling point.”

In his last year at school in Tianjin, Zhou began espousing socialist concepts. One of his last school essays, written in May 1917, stated: “unless social classes are eliminated, there is no hope for equality.” He graduated the following month, writing to friends that he hoped they would “meet at the time that China has risen high again in the world.” In the autumn, Zhou boarded a ship for Japan, hoping to enter a prestigious university. He wanted to learn how Japan, with a culture and society similar to China’s, had managed to become a powerful player in East Asia. But, as Zhou wrote in his diary, his introduction to Japan was “lonely,” with “no progress” in his attempts to learn Japanese. He wrote of frustration, depression and what Chen terms “Buddhist-style nihilism.”

By February 1918, however, Zhou was hooked on a new endeavor. He began reading the intellectual journal New Youth (新青年), edited by Peking University professor Chen Duxiu, who later became one of the CCP’s founders. Zhou declared himself in sync with the journal’s advocacy of “anti-confucianism, celibacy and revolutionary literary critique.” Experiencing a “rebirth” of ideas, Zhou also wrote that marriage was unnecessary, and that “there exists no difference between male and female in a free love.”

Failing to enter a Japanese university, Zhou returned to Tianjin in April 1919 — just in time to take part in the tumultuous May 4th Movement, where Chinese students and intellectuals protested against the terms of the post-WWI Versailles treaty, which ceded German “rights” in Shandong province to Japan. Zhou’s activism accelerated, and he was jailed for six months. After his release, he traveled to France in 1920 to further explore socialist ideals abroad, and to recruit members for the nascent Chinese Communist Party. In Paris, Zhou burnished his internationalist credentials for future diplomacy, and met contacts who helped launch him towards a senior CCP leadership role. It was there, Chen writes, that he fully accepted communism as his “ideological lodestar.”

Zhou first met Mao Zedong in Guangzhou province in 1924, where Mao was training organizers of peasant movements. Zhou also began teaching at the Whampoa Military Academy (established that year by Sun Yat-Sen to train China’s revolutionary officers) and met its founding commander, Chiang Kai-shek. Even as the CCP-KMT relationship veered between cooperation and conflict, this connection helped ensure Zhou and Chiang shared a mutual respect.

By now, Zhou was a professional revolutionary, apparently sincere in his willingness to die for the cause. But even if we understand how Zhou became a communist, how did he become the enabler of Mao’s brutality? How did he become a killer?

It was in Paris that Zhou fully accepted communism as his “ideological lodestar.”

Fast forward to November 1927. Shanghai was flooded with blood, betrayal and intrigue, in the wake of Chiang Kai-shek’s violent anti-communist coup that April, killing or jailing tens of thousands. Newly arrived, Zhou took the role of the Party’s spymaster, head of its new security and intelligence service (特科).

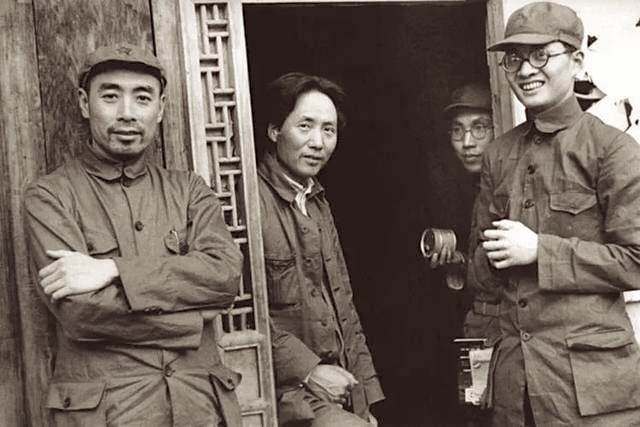

The fledgling Party faced many threats, but Chen argues that Zhou’s interactions with Mao were his “toughest challenge.” The two didn’t always agree on battlefield strategy. Zhou scrambled to impose Party discipline, set up a secret radio transmitter station, handle communications with the Comintern in Moscow, and recruit KMT personnel as spies. He often changed names, wore disguises or grew a beard, and he never stayed in one place more than a month.

“It was almost a miracle,” Chen writes, “that Zhou survived the powder keg filled with explosives that was Shanghai.” The worst was yet to come. After setting up CCP’s intelligence service, Zhou put his principal aide, Gu Shunzhang, a man with underworld connections, in charge — but KMT agents in Wuhan arrested Gu in April 1931. Under interrogation, Gu caved and promised to divulge all his secrets — on condition that he reveal them to Chiang Kai-shek in a face-to-face meeting. This was a serious blow to Zhou’s underground network. But in a lucky break, Chiang required a couple days to travel to see Gu — enough time to allow many CCP assets to evacuate.

In retribution, Zhou ordered his agents to kill Gu’s wife and eight other family members, including a two-year-old boy. This was “killing the chicken to scare the monkey,” and Chen condemns it as an “inhumane” act that showed a “cruel and ruthless aspect of his character.” He writes: “Any revolution is brutal. In the name of ‘justice’ and ‘necessity’, a revolution is capable of fully exposing the most barbaric aspects of human nature.” Intriguingly, when Zhou ordered the killing, Chen notes:

His usual calm demeanor gave way, he confided in his subordinates that he was unsure whether this was a good or a bad decision. ‘Let history judge,’ he said.

The massacre of Gu’s family is a ghastly indictment of Zhou’s character. But many less dramatic incidents also documented Zhou’s acquiescence to Mao’s abuses and authority. These were the early days of Chinese communism, when the Party faced existential challenges. When Zhou returned to China from Europe in 1924, he had considerable “street cred” within Party circles and was considered Mao’s superior. Chen reminds us:

Unwilling to use his power and authority to compel Mao’s obedience, [Zhou] showed Mao patience and respect. … [There] was a subtle fearfulness … probably an early manifestation of the unique and even mysterious chemical reaction that would characterize the relationship between the two men.

By 1934, Zhou faced a crucial decision. He was preparing for the Long March, the CCP and Red Army’s legendary trek to their future stronghold of Yan’an in Shaanxi province. Mao was either to stay at his besieged position in Jiangxi province, or to accompany the main force on the march. The decision was mainly up to the heads of the Party’s military and political affairs, Otto Braun and Bo Gu, with considerable input from Zhou. Mao wanted to leave, and Zhou’s support enabled the military to allow him to.

Had Mao stayed behind, Chen considers, even if he survived “he would have been separated from the CCP leadership and thus would have lost the opportunity to re-emerge and claim the position of the Party’s top leader.” The decision to allow Mao to leave was a truly pivotal moment which, but for Zhou’s support, could have led to a dramatically different trajectory for the party.

The fatal flaw of strongman rule is that the strong man usually wants to keep on ruling.

As it was, the CCP triumphed over the KMT, and when the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, it was with Mao at the helm of the Party, and Zhou as his Premier. The symbiotic nature of the Zhou-Mao relationship may well have helped the CCP survive some early existential challenges. But when their mission shifted from making revolution to governing China, cracks began to appear, both in their relationship and within the system itself. The Party’s woeful lack of economic expertise resulted in devastating famines which lasted several years. Mao’s obsession with power struggles and pitting personalities against one another reached near-pathological levels. As years passed, it became clear that the fatal flaw of strongman rule is that the strong man usually wants to keep on ruling.

As Mao became increasingly unmoored during the Cultural Revolution, Zhou may have seen the risk that the CCP was losing its way. Chen’s book has a memorable anecdote about how Zhou reacted to news of the death of Lin Biao, China’s Defense Minister and Mao’s handpicked successor. A brilliant military commander, Lin and his family died in a September 1971 plane crash. Officially, Lin had betrayed Mao and attempted a botched coup, then tried to flee. Yet many Chinese believe Lin had fled, afraid of being purged after his relationship with Mao soured.

Lin’s death made Zhou the de facto heir apparent, even though he had always been terrified of the prospect. While other officials appeared to be celebrating, Zhou’s mood was dark. A Politburo member named Ji Dengkui and another colleague visited Zhou, who was alone, to discuss the episode. Chen reprints this part of Ji’s account:

I said “Lin Biao has destroyed himself. From now on we can give good attention to the country’s economic reconstruction. This is a happy moment.” These words were obviously too much for [Zhou’s] overburdened mind. His tears flew down, quickly turning into a cry. Louder and louder he wailed, choked with sobs … finally he calmed down. After quite a while he said “you do not understand. It is not finished yet.” He stopped and did not utter another word.

If other cadres were rejoicing, why was Zhou upset? Chen speculates:

It seemed likely that Zhou believed Mao’s Cultural Revolution was a catastrophe, and understanding that he could be seen as an accomplice of Mao’s, he foresaw the difficulty he would encounter in facing the judgment of the Chinese people and of history. … Was Zhou gripped by the fear that he might follow in Lin’s path?

Zhou’s fears were not unfounded — even he didn’t escape critique during the Cultural Revolution. In 1973, a series of “criticize Zhou” Politburo meetings examined six major “mistakes” of his “political line.” Ever-sensitive to the shifting winds, Zhou proactively criticized himself, going back to decades-old incidents involving past or purged Party leaders. He called himself a “criminal,” and claimed that if not for Mao’s magnanimous efforts “to rescue me, educate me and give me the opportunity to correct my mistakes, I would not be standing in front of you today!” The real agenda of the meetings was for the ailing Mao, the Gang of Four and other senior leaders to figure out who would side with whom in the inevitable succession struggles ahead.

When Zhou passed in 1976, the public outpouring of grief included a mound of funeral wreaths laid around the obelisk in Tiananmen Square by a crowd of mourners, who gathered there on April 4th for Qingming Festival, a traditional day of mourning. The size and intensity of the crowd was not only a gauge of Zhou’s popularity, but also a rebuke of Mao. Alarmed by the spontaneous display of public emotion, authorities ordered a crackdown, which was termed the “first Tiananmen Square Incident.”

Chen’s last chapter portrays Zhou on his deathbed, terrified that past mistakes and bad blood between him and Mao could resurface. After his death, Zhou’s widow demanded, successfully, that all past critiques of him be destroyed. This was done, writes Chen, “in order to preserve her late husband’s reputation and, probably, cover up some of the darkest episodes of his service under Mao.” Such efforts would have helped keep Zhou’s reputation relatively positive, both domestically and internationally, at least for a time.

The habit of erasing a Chinese leader’s excesses, in order to keep his image untarnished, is part of a collective amnesia in which the disturbing elements of entire periods of Chinese history are never aired in public. Back in the 1990s, Beijing’s decision to ban Gao Wenqian’s biography of Zhou might have slowed the speed with which some of the late Premier’s past brutality became common knowledge. But today’s social media can make such news almost instantaneously accessible.

To be sure, there are still classified documents related to Zhou that have not yet become accessible. But isn’t there enough evidence to make the case against him already? For how long should Zhou’s reputation be protected? The answer may be the same one that Zhou cited after he ordered the Gu family’s massacre: “Let history judge.” ∎

Melinda Liu opened Newsweek’s Beijing bureau in 1980, and has lived and worked in Beijing for more than 25 years, reporting firsthand on key moments in post-Mao China. She co-authored Beijing Spring (1989) and co-directed the documentary film Doolittle Raiders: A China Story (2017). In 2006 she won the Shorenstein Journalism Award in recognition of her reporting on Asia.