Reviewed: Cheng Li, Contested Environmentalisms: Trees and the Making of Modern China (Stanford University Press, 2025)

April 3 was, presumably, a busy day for China’s leadership. Donald Trump had just announced a sweeping round of tariffs on Chinese imports, posing a major threat to their economy. Yet the Politburo Standing Committee and other senior officials had another important task to attend to that day — planting trees.

Shovels and buckets in hand, they joined red-scarfed Young Pioneers in sprucing up a sandy stretch of land in an outlying Beijing district. Xi Jinping himself planted red pines, plum trees and Chinese rubber trees, among others. During the photo opportunity, he extolled the virtues of afforestation, noting that China’s forest cover had increased to over a quarter of the country, but adding that more effort was needed to give the Chinese people what a Xinhua report described as “more green around them, and more beauty in front of their eyes.”

This might seem in line with the kind of green bromides that politicians around the world use to show their commitment to the environment. But Xi’s words and actions — and possibly even his timing, a day before Tomb-Sweeping Festival — fit into a much longer tradition: That of Chinese leaders seeing trees as essential for the country’s health.

In 1915, Yuan Shikai designated Tomb-Sweeping Festival as Arbor Day.

How trees have shaped China, and how China has treated its trees, is the topic that Cheng Li, a cultural historian at Carnegie Mellon University, tackles in his new book Contested Environmentalisms: Trees and the Making of Modern China (Stanford University Press, 2025). He gives an overview of China’s Republican and Maoist eras, and shows how, throughout this history, tree planting was seen as crucial for China and its people.

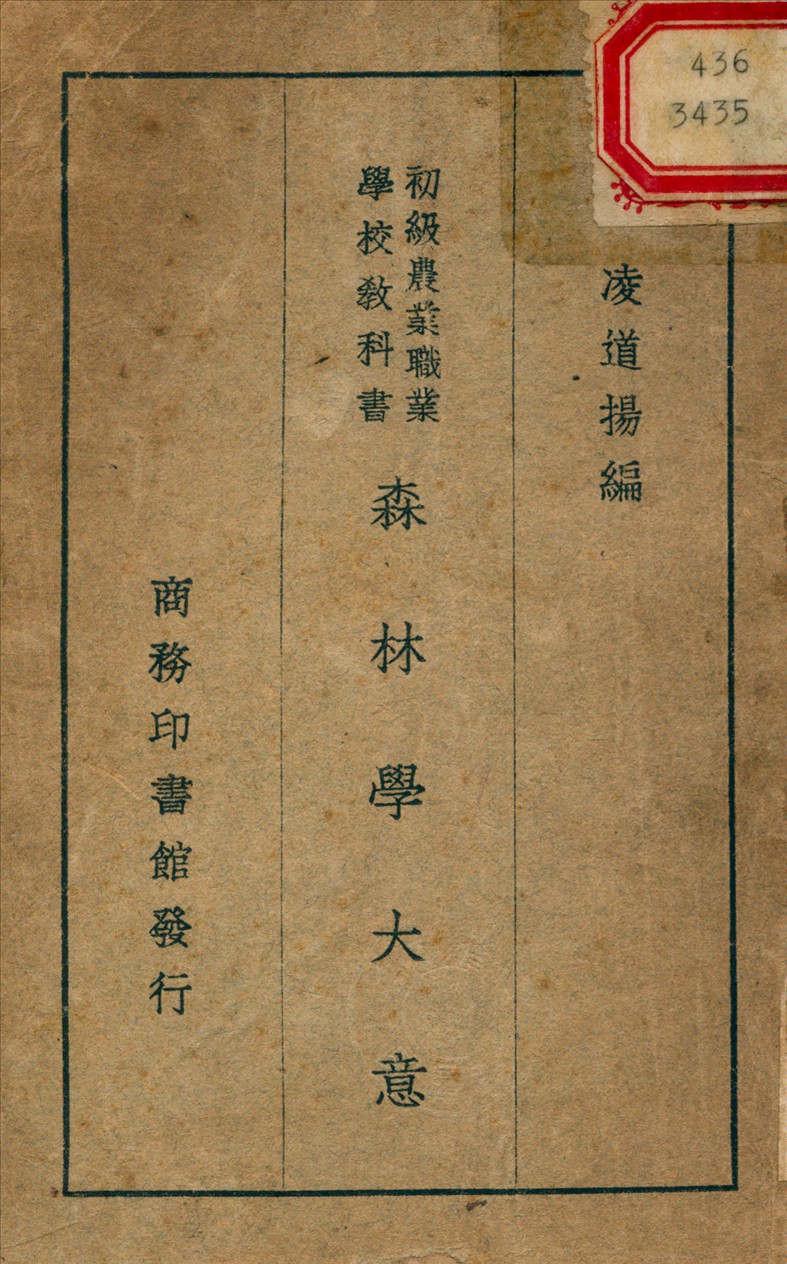

China’s environmentalist movement sprouted in the early 20th century. One of its earliest voices was forester Ling Daoyang (凌道扬), born in 1888 in the county of southern China that is now Shenzhen. After earning his master’s degree in forestry at Yale University (the first American institution to open a forestry school) in 1914, Ling returned to China to take up a government job at the Ministry of Agriculture and an academic post as director of the Forestry Department of Nanjing University. Here, Ling argued for the conservation and planting of trees. His book Main Ideas of Forestry (森林学大意, 1916) extolled the uses of trees beyond providing wood: stopping soil erosion; increasing rainfall and oxygen levels; and nurturing mental and physical health.

At the urging of Ling and others, in 1915 Yuan Shikai, the first president of the new Republic of China, designated early April’s Tomb-Sweeping Festival as Arbor Day (植树节) — a day for planting trees that originated in 1872 in America, where it is now celebrated on the last Friday of April. In 1925, when the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen passed away, the date of Arbor Day in Shanghai was moved to the day he died, March 12. Sun, who had also been influenced by Ling’s work, regarded forests as crucial for the building of the nation: they could help avoid droughts by adding atmospheric moisture (thereby preventing famines and social unrest) and provide wood for industry when chopped — a tension between planting and cutting trees that is a common thread in Li’s account.

In the 1930s Chiang Kai-shek, Sun’s eventual successor at the head of the Nationalist Party (KMT), integrated tree planting into his New Life Movement. This campaign to educate Chinese citizens in neo-Confucian values, Li writes, “borrowed the German belief that interaction with the natural environment helps shape a strong national character.” Chiang would join tree-planting activities wearing his military uniform. Yet while tree planting for the Nationalists had become a symbolic act, for the Chinese Communist Party it was a matter of life and death.

When, in 1935, the Communists ended their Long March in Yan’an, northern China, they found themselves in a region that suffered from soil erosion and lack of rainfall. They promoted tree planting in an effort to curb those issues — and continued to do so on a national scale after winning the Chinese Civil War in 1949. In 1956, Mao Zedong returned to Yan’an to launch the Greening the Motherland Campaign, turning what had begun as an attempt to stop soil erosion into a nationwide campaign to involve young people in the building of a new China. To Mao, Li writes, this was “not so much an ecological initiative to improve the Yellow River Valley as a continuation of his desire to guarantee the survival of his revolution.”

The Great Leap Forward, an industrialization campaign which Mao started two years later in 1958, put afforestation efforts into higher gear, at least on paper. The Party newspaper People’s Daily claimed in March 1958 that the people of Shanxi province had in just one month planted 100 million trees along the Yellow River. Yet deforestation, which Li mentions only fleetingly, was the true reality of this period. Large tracts of forests — “at least 10 percent” according to Judith Shapiro in Mao’s War Against Nature (Cambridge University Press, 2009) — were felled across the nation to power the backyard furnaces that Mao had urged people to build in a misguided attempt to increase the production of steel. This redirection of effort, combined with poor harvests, led to the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-61 in which tens of millions died (some surviving by eating tree bark).

Tree planting nevertheless continued to be a political goal. For the Communist Party, afforestation became a tool for sinicizing the ethnic minorities of China’s borderlands. Tree planting, went the theory, would help them to drop their backward nomadic lifestyles and settle into communes. The Army’s Reclamation and Battle Song (军垦战歌), a 1965 documentary film about tree planting in Xinjiang, Li writes, “aims to show that the success of tree planting justifies the state’s control in ethnic areas under the veneer of environmental conservation.”

The Cultural Revolution of 1966-76 saw more environmental devastation. Li depicts this through the 1985 novella The King of Trees (树王) by Ah Cheng, about sent-down urban youth in the countryside, likely of Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province, who cut down an ancient forest against the will of the local population. In the post-Mao era, the Environmental Protection Law of 1979, enacted in 1989, attempted to redress the damage. But as the Chinese economy developed, these efforts proved no match for continued demands for lumber.

Contested Environmentalisms skips over the 1990s and 2000s — when forests continued to make way for economic development but deadly floods in 1998 rekindled afforestation efforts — to 2016, a century after the first Arbor Day, when the e-finance app Alipay launched a feature called Ant Forest. With this, the tech giant Alibaba rewards its hundreds of millions of users for environmentally friendly activities (such as cycling or bringing a reusable mug to coffee shops) by planting trees on their behalf — 548 million of them as of 2024. To Li, this is a fundamentally profit-seeking enterprise, a “textbook case for mixed environmentalism” whose ultimate goal is driving users to Alibaba’s e-commerce businesses, which produce mountains of packaging waste.

While tree planting for the Nationalists had become a symbolic act, for the Chinese Communist Party it was a matter of life and death.

Li’s book is short and accessible — though not unafflicted by the drudgery of academese. (Interestingly, he mentions in the acknowledgements that ChatGPT 4.0 assisted him with polishing the grammar of a small part of the manuscript.) He describes in detail China’s various afforestation schemes, yet largely forgoes discussing their efficacy. Only toward the end of the book, for example, does the reader learn that Ant Forest has been more successful in fighting desertification than the Chinese government’s own efforts.

Li is mostly interested in the political and cultural discourse around these initiatives, but it’s unclear to what degree officials’ grandiose claims, as well as the cultural works Li discusses, reflected or affected what was actually happening to China’s forests. An exploration of the realities of afforestation would help readers gauge whether the litany of tree planting projects throughout Chinese history had merit or are merely bluster. The author sows some seeds of confusion himself by mentioning on one page Mao’s “successful environmental initiatives,” then on the very next page describes the same era as undergoing a “destructive” revolution during which natural resources were “recklessly exploited.” How much of the motherland was actually greened?

Another ostensible omission is discussion of Communist leaders after Mao — most notably Xi Jinping, the Chinese leader under whose watch China has made unprecedented environmental progress, including cleaning up air pollution and developing green tech, and a continuation of his predecessors’ tree planting efforts. In July 2020, during Xi’s second term in office, amendments to China’s Forestry Law enshrined Arbor Day (March 12) into law.

Tree planting, in our current climate crisis, has become a contentious topic. Planting an enormous number of trees is a favorite global warming solution for governments and companies alike. The argument is that trees absorb CO2, and so can compensate for our fossil fuel emissions. Yet critics dismiss this as greenwashing because projects often overstate their effect. The potential of trees to bring down atmospheric CO2 levels is limited: according to one academic, 100 million mature trees will, in a year, absorb the same amount of CO2 that humanity emits every half hour. And without proper long-term care, headline-grabbing projects leave little impact: a one-hour blitz in the Philippines in 2012 to plant a million mangrove trees saw just two percent of seedlings survive.

That is not to say that planting trees is useless. But in many cases, it has been less useful than advertised. Planting trees and having them grow to maturity is harder than one might assume. In his book, Li does not tell the reader what the net result is of China’s century of afforestation campaigns and deforestation crises, a missed opportunity to shed light on a now controversial practice. But Chinese leaders have little doubt on whether to keep planting or not. It is a job, Xi told his fellow arborists in early April, that should “continue generation after generation.” ∎

Header: Pang Jun (龐均), “Youngsters! Use both your own hands to make our great motherland greener,” April 1956. (Chinese Posters/Stanford University Press)

Kevin Schoenmakers is a New York-based freelance reporter and editor. He was previously a founding editor of Sixth Tone in Shanghai, China correspondent for Dutch news wire ANP, and Features Editor at Rest of World.