Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

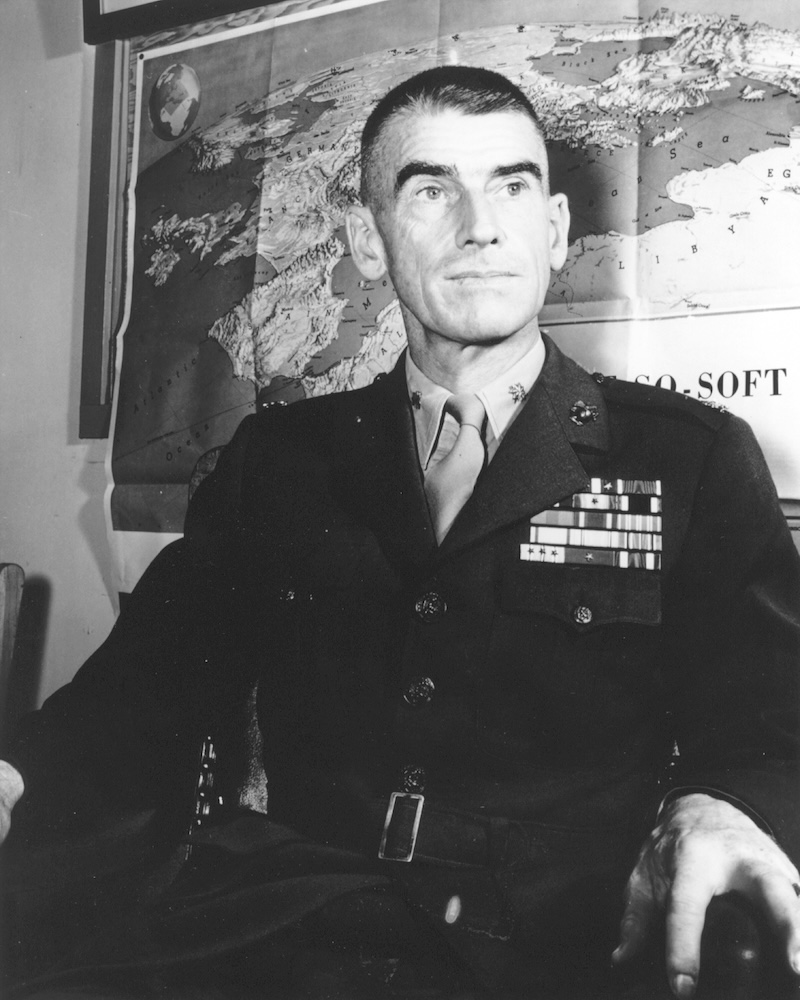

Ed: In The Raider (Knopf, May 2025) Stephen R. Platt tells the story of forgotten WWII icon Evans F. Carlson, a U.S. Marine Corps officer who embedded with China’s Communist forces in 1937-38 on a private mission for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His travels with General Zhu De’s Eighth Route Army into territory occupied by Japan inspired him to later found one of the first U.S. special operations forces in the Pacific War, “Carlson’s Raiders.” We pick up the story at the start of his journey, with Carlson writing a letter to FDR promoting the Communist guerillas as a model for the U.S. military.

Evans Carlson wanted Roosevelt to know what he had learned about Zhu De’s army because he thought China would be a natural ally for the United States in the case of a war with Japan. He explained that the Communists had developed “a style of military tactics quite different from that employed by any other military force in China, and, indeed, new to foreign armies as well.” Their army was agile and fluid — he described it as being like an eel squirming in and out between the Japanese enemy’s units, or a swarm of hornets attacking an elephant. “They strike and disappear, cut lines of communication, attack repeatedly during the night so that the opponents cannot sleep,” he wrote. He said they were finding ways to fight the Japanese that no other Chinese army could yet approximate.

Carlson explained to FDR that the Chinese Communists were not just formidable fighters but also remarkably easy to get along with, “quite unorthodox in their mental processes, in their conduct and in their action.” They were “habitually direct in speech and action.” They were welcoming and cordial, with none of the stiff formality that made regular Chinese officials difficult to deal with. He reserved his greatest praise for Zhu De, whom he described as “a kindly man, simple, direct and honest. He is a practical man. He is humble and self-effacing. And yet he is forthright in military matters.”

Although Carlson supported all parties in China, it was clear from the letter where he believed China’s best hope for the war against Japan lay. Zhu De, he told Roosevelt, had commanded the Red Army through its survival of Chiang Kai-shek’s five encirclement campaigns; he had led it on the Long March; and as far as Carlson could tell, he had won multiple victories against the Japanese in the north, a feat yet to be achieved by Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT forces with their stumbling retreat from the most important cities in eastern China.

Carlson advised Roosevelt that if the United States and China should become allies against Japan, American troops would need to be educated in advance to erase their prejudices about the Chinese people. (This, from a man who had come to China 10 years earlier wanting to teach the “slant eyed people” a lesson.) “The knowledge which our American people possess of China and the Chinese is very meager,” Carlson wrote, “based largely on the Chinese laundrymen they meet in their hometowns, or on what the foreign missionaries tell them.” To combat this, he thought American troops should be instilled with the willingness to understand the Chinese and cooperate with them as equals. Echoing his conversations with Zhu De about the hopeful possibilities for an alliance against Japan, he told Roosevelt that if it came to war, a feeling of “close comradeship” could be encouraged between the American and Chinese troops, which not only would enable them to undertake combined operations, but would also (and this he underlined) “result in a closer bond of friendship after the war.”

Carlson said he knew it wasn’t enough simply to relay what he had learned at Zhu De’s headquarters. He had to see the army’s operations in the field for himself, to confirm the reality of what he had been told. He wanted to see the partisans at work, to judge with his own eye the army’s success in organizing Chinese civilians. And that, he explained, was why he had decided to continue north into the areas where the Eighth Route Army operated behind Japanese lines. “I must see how these ideas and theories work out in practice,” he said. His plan was to depart the following morning, on December 25, 1937, with a detachment of Zhu De’s troops. And yes, he assured the president, he was aware of the irony that he would be leaving for the northern front with an army of Communists on Christmas Day.

Carlson explained to FDR that the Chinese Communists were not just formidable fighters but also remarkably easy to get along with.

Up early on the morning of his departure, Carlson rolled his sleeping bag into a tight bundle and packed his belongings into his haversack. The other American at Zhu De’s headquarters, the American journalist Agnes Smedley, came over for a final breakfast. They went out to the south wall of the town to meet up with a patrol that was heading north to bring supplies to Nie Rongzhen’s 115th Division in the Wutaishan region of northern Shanxi. The distance there was about 230 miles overland to the northeast, but the direct path ran through the provincial capital, Taiyuan, which was occupied by the Japanese, so their planned route was circuitous and ranged much further, giving Taiyuan a wide berth. Zhou Libo came along, partly to continue as Carlson’s interpreter and partly because he was an aspiring writer and wanted to document the war zone for readers in China.

Carlson and Zhou Libo did not carry weapons, but an escort of 28 soldiers in two squads accompanied them for protection. Between the soldiers of the patrol, the two squads of bodyguards, and a handful of travelers that included Carlson and Zhou, there were 45 men on horseback or on foot in the group and 14 draft animals laden down with boxes of bandages, medicine and other supplies. Zhu De came out to see them off. Agnes and Carlson said their goodbyes. As they were getting ready to depart, two Japanese planes swept down out of the north, flying low in the distance, but they did not seem aware of the army headquarters. They dropped a couple of desultory bombs on the city of Hongtong, the county seat a few miles to the east, then turned back north and disappeared. Once they were gone, a small advance guard of the patrol set out first on the road, followed by the rest of the column in a long, single-file line.

Leaving the familiar valley and heading north, Carlson’s patrol rode into a dusty and inhospitable loess landscape. Desolate, treeless mountains rippled all around them, fringed with ice from frozen streams that looked to Zhou Libo like silver chains hanging from the hillsides. When the cold got to be too much for them, they got off their horses and walked to generate warmth. Ancient, gnarled trees, brown and leafless, stood sentry at the sides of the deeply rutted road.

They were still far enough south of the Japanese occupation forces that they felt safe. Aircraft sightings were rare and the local county governments were still in the hands of officials loyal to Nanjing. There were other Chinese forces in the region besides the Communists, mainly provincial troops under control of the Shanxi warlord, who was loyal to the KMT. Carlson wasn’t terribly impressed with them (nor with their leader, whom he met later). Occasionally they encountered deserters from those forces, who struck him as “shifty-eyed fellows.” Some had become bandits. A few days out from Hongtong, Carlson saw a larger body of provincial troops drilling in a field and as far as he could make out, all they were doing was marching around, learning how to goose-step like Germans. What a waste of time, he thought, at a time when men needed to learn how to fight.

Carlson and Zhou Libo spent their New Year’s in a local county seat, waiting for their patrol to continue north. The country administration put on a grand show for Carlson, of a kind that would be repeated many times on his journey north. On the cold, windy morning of January 2, 1938, a county magistrate assembled about 8,000 supporters of the war effort outside the walls of the town where Carlson’s column had paused for the night. The partisans and self-defense forces formed up in lines and Carlson was invited to inspect them as they stood at attention. They carried a hodgepodge of different weapons, everything from rusty old swords and ancient, muzzle-loaded muskets to modern, light machine guns. Many simply carried spears. The leaders had set up a reviewing platform, adorned with a captured Japanese flag, where they asked Carlson to stand as the crowd marched in formation in front of him, singing military songs and chanting patriotic slogans:

Down with Japanese imperialism.

Unite to defeat the Japanese fascists.

China fights for the peace of the world.

All of the fuss left him feeling suspicious. A large banquet followed the review, where his hosts ate almost nothing even though there was enough food to feed half the column. The same would be repeated, against his protests, by local non-Communist officials at further stops along the route. He wrote in his diary that there was too much “keqi” for his tastes — keqi being one of those Chinese words that foreigners preferred to use in the original because it seemed to them to defy easy translation. It meant politeness, but a particular kind of formal, ceremonial politeness that Carlson, for one, found forced and insincere. He saw it as only so much “bowing and scraping” and “ceremonious exchange of platitudes.” He wanted to be an invisible observer, not the center of attention, though that would not turn out to be an easy thing to accomplish.

Their column continued its progress the next morning, its length expanding with the addition of 250 soldiers from the Eighth Route Army’s 129th Division who were returning to their headquarters further north in the province. There was also a propaganda group that seemed to be comprised entirely of young boys of about 12 years old. One of the boys — “little devils,” the Chinese soldiers called them — explained that he was in the army because his father, who wanted to send one of his sons to fight, had drawn his name from a bowl. Another, who was 14, said that he had joined the Red Army when he was eight. Zhou Libo asked him if he missed home and he said no, he didn’t. Zhou asked why he joined the army. He said he joined to save China, and to save himself.

Two Japanese planes swept down out of the north, flying low in the distance, but they did not seem aware of the army headquarters.

Carlson hardly rode his horse at all, preferring the exercise of walking each day’s leg of the journey. Two more days brought them to the headquarters of the Eighth Route Army’s 129th Division. By this time, Carlson was starting to notice patterns. The Communist headquarters were always in small villages, not in the cities nearby that would have been more convenient and comfortable, yet where there was also a greater risk of Japanese air raids.

As he had done in Zhu De’s headquarters, Carlson spent hours talking to the leaders of the 129th Division to learn how they had been fighting, of the tactics and outcome of their engagements with the Japanese. One evening, around a table illuminated by candlelight, he fell back on his coursework at George Washington University to go through what he understood of Japan’s long-term relations with China. Carlson wanted to encourage the men he was speaking with, so he told them that in recent generations Japan had met with no major defeats or serious obstacles to its expansion in northeast Asia — until now, in China.

The Japanese simply hadn’t expected to meet with such fierce resistance at Shanghai, he said. They thought Chiang Kai-shek would capitulate quickly, but now the war was becoming a crisis for Japan. Between Manchuria, North China, and the region around Shanghai and Nanjing in eastern China, there were more than a million Japanese soldiers committed to the Chinese mainland, with another million likely being mobilized. They would exhaust themselves. Japan, he told the officers around the table, was in the process of learning that it was not, in fact, the top-tier world power it imagined itself to be. If you can just continue to hold out, he told them, the world’s sympathy for China will grow, and with it will come their willingness to send aid.

Carlson began to warm up to the partisans and self-defense forces — the “masses,” as it were — always on display, standing in amateur formation at the villages and towns his column passed. The more he saw of them, the more he became convinced that they were genuinely patriotic Chinese peasants rather than just well-orchestrated scarecrows arranged for his benefit by local officials eager to impress the American. And it likewise became clear just how important it was that he was American — the first representative of the U.S. government (or any other Western government, for that matter) to come view the war up close, to talk to people face-to-face, which meant he was the first person who stood a chance of conveying to the outside world that Chinese people far beyond the ranks of the KMT armies were trying to do their part to hold out against Japan.

Their hopes for the message he might bring home were reflected in the unbounded enthusiasm people showed when he came through. At one town along the way, he noted in his diary, “people came pouring off the terraced village above to the trail below. They carried banners and flags, formed [a] line quickly — children, young and old men — and saluted. They were welcoming an American comrade and very genuine about it.” At other towns, people regularly turned out and cheered as the column passed. Sometimes it seemed the entire town was out by the road with banners. He never got over his aversion to banquets and “keqi” government officials, but he found himself increasingly moved by the sentiments of the ordinary people he talked with.

It was clear that many of the local officials had hopes for American intervention that were patently unrealistic. Some seemed to imagine that Carlson’s arrival marked the beginning of a formal American military presence in North China. Banners pasted to the walls of homes in one village his column passed — which Carlson couldn’t read, and it is unclear whether anyone translated them for him — proclaimed “Welcome, American patriots, to join China’s war of resistance.” A companion banner read, “Welcome, American military forces, to fight in the war in China.” Such assumptions of American involvement disturbed Zhou Libo, not just because they were so mistaken as to the reasons for Carlson’s mission but because they implied weakness on the part of China.

When local officials questioned Carlson directly about American intervention, he tried to deflect them with vague assurances that the American people were sympathetic to China, and that the two countries had always enjoyed friendly relations in the past. If the officials continued to press him, demanding to know why America hadn’t yet joined the war, he tried to turn it around. If Mexico were an imperialist power and it were trying to invade the United States, he asked them, would China feel compelled to intervene? That seemed to work up to a point, but he knew they weren’t always satisfied. “They would usually still murmur that America was the defender of democracy and liberty,” he told Roosevelt. “The Chinese seem to be pretty well sold on that idea.”

It was clear that many of the local officials had hopes for American intervention that were patently unrealistic.

The further north they went, the more strongly Carlson and Zhou Libo could feel the presence of the Japanese who had come through before them. In one village, a group of old men were burying three of their neighbors. One had been shot for refusing to kneel before a Japanese soldier. Another was shot for failing to follow instructions shouted at him in a language he could not understand. For the third, they said, there was no reason at all. The houses in this impoverished region were built of mud and soil, and the wood of their window frames and doors was a precious commodity — even firewood was scarce, and children had to walk miles to collect it for their families. The Japanese apparently knew the local value of wood, for as Carlson passed through villages they had recently occupied he could see where all of the window frames and doors had been ripped out and burned out of spite. (“What vandals!” he wrote in his diary.) The harvests of grain the people stored carefully on their roofs to survive the winter were also burned. In some cases, where starting a fire apparently hadn’t been convenient, Japanese soldiers had defecated and urinated on the peasants’ food stores before moving on.

The images of death and cruelty were overwhelming. In one town early on, it was the remains of a series of Japanese aerial bombings, which had destroyed several hundred homes in a town that had no military presence. The local girls’ primary school lay in ruins and they could see scraps of family letters and student papers lying among the rubble. In another village further north, several witnesses told them how the Japanese had imprisoned 200 people in a building, then ordered one of the villagers to set it on fire. When he refused, they disemboweled him with a bayonet. They repeated this process until someone finally obeyed. The villagers said there were pigs and sheep inside the building as well, and as it burned, the screaming of the children blended with the howls of the dying livestock. The Japanese soldiers just watched, laughing all the while.

Even the lesser crimes were heartbreaking: at one small town, a middle-aged farmer came out to the road and pleaded with Carlson and Zhou Libo to come and bear witness to the place where all of his grain had been burned by the Japanese. They said they couldn’t go. Zhou wrote in his diary that it was too easy to envision the scene they would find — the pile of black ashes where the man’s precious crops had been stored, the old farmer, weeping into his large, rough hands. They had seen enough suffering already. Most of the town’s residents had fled for safety, and the old farmer was one of the first to come back. The empty town felt like a vast burial ground, and they were relieved when it was time for the column to move onward.

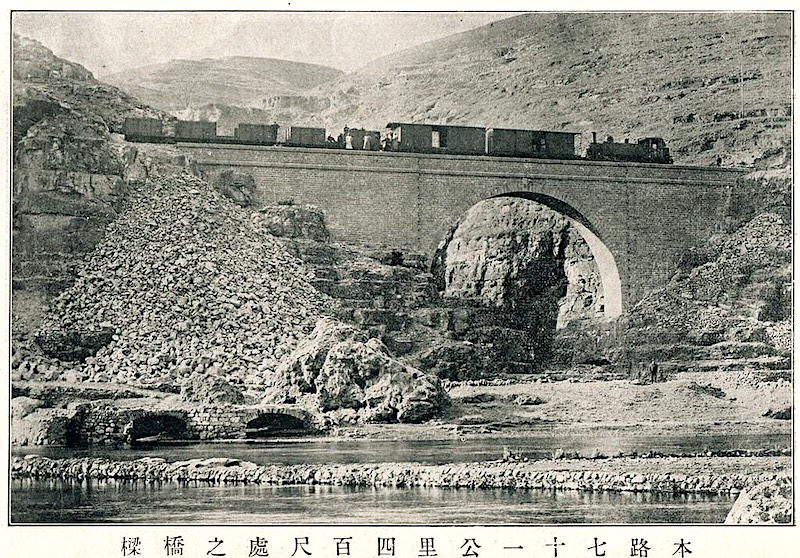

The formal Japanese line of control was the Zhengtai Railway, which cut across the upper half of Shanxi province, part of the east-west line that connected to Beijing. As the Japanese depended on it for moving supplies and personnel, it was well protected with garrisons in the major towns along its length that sent out patrols to guard its more remote sections. Carlson’s column had been growing as it gathered more travelers from each base they visited — it now numbered about 600 men (and one woman) as well as a veritable herd of pack animals. To get to the rear base areas, the entire slow-moving column had to cross the railroad together. Even with the information they had from the local self-defense forces, finding a safe place and time to get across with such a large body of people and animals was not easy.

They made their first attempt in mid-January, but had to abort when they learned that the Japanese had recently occupied the county just north of where they planned to cross. So they continued east for sixty miles, parallel to the railroad, aiming to cross at a town named Dongyetou. After beefing up their escort forces with two more companies of armed soldiers, they stopped to spend the night at a village two miles to its south. While they were unpacking their bags, however, a peasant from the self-defense forces rushed in with the news that an active Japanese column of 700 soldiers was just a few miles away, approaching Dongyetou, likely on a foraging mission. The ranking officer in Carlson’s escort forces, a 21-year-old regimental commander named Chen, took the escort soldiers with him to investigate, and asked Carlson to wait behind with the noncombatants — the orderlies, the kitchen section, the radiomen. Carlson said he would prefer to come along, but Chen said nothing interesting was going to happen.

Carlson could hear the firing of artillery a few miles away as the Japanese shelled Dongyetou, and it was maddening not to be able to go along and watch close-up as he had done in Shanghai. At the same time, however, he realized now that his presence would be a serious distraction for the commander — if an American observer should be killed on Chen’s watch (or perhaps even worse, captured), the whole Eighth Route Army might suffer; certainly the KMT officials in Hankow would play it to their own advantage and tell the Americans that the Communists were to blame for his death.

Carlson had written a letter to the U.S. Ambassador Nelson Johnson absolving the Communists of responsibility for his safety, and he had left a similar one with Zhu De as well, but it was a more sensitive situation than a letter could compensate for. In any case, Carlson, in spite of his frustration, did not want to argue with a fellow officer in front of his men — especially one as young as Chen — so he reluctantly agreed to wait out the engagement with the orderlies and radiomen. They were directed to retreat to a village up in the mountains a little ways to their south. Fifteen minutes into their hike, just as they were starting up the trail toward their refuge, Carlson turned around to look at the view back down the slope and watched as an advance force of Japanese cavalry swept into the village he had just left.

That evening, Chen came back to their camp and rolled out a map to show Carlson the situation. There were two Japanese columns in the area, he said, and it looked like they were trying to converge on Dongyetou. The crossing would now be impossible, but he had sent out scouts in search of weak points in the Japanese lines of communication and he was going to keep moving with the escort forces and see if they could find an opening to cause some damage to one of the columns. Carlson asked again if he could come along and Chen hesitated. Changing the topic, he asked Carlson what he would do with his forces under this scenario. Carlson said he would attack each of the Japanese detachments separately, before they could join forces. He said Chen should choose the sites of engagement carefully. Chen agreed. Carlson asked one more time if he could come along. Chen urged him to stay in the rear.

He wound up being stuck at camp for four days with his diary and his Emerson essays, practicing Chinese with Zhou Libo while Chen’s detachment played cat-and-mouse with the Japanese forces in the vicinity. It began to snow and soon the hills were covered in white and the trails were obscured. One of the other men who had been told to stay behind was a wounded officer who was on his way back to the rear areas. He consoled Carlson by reminding him that their mission was to cross the railroad safely, not to fight. “He is right, of course,” wrote Carlson in his diary.

On their third attempt, a week later, they finally made it across.

The further north they went, the more strongly Carlson could feel the presence of the Japanese who had come through before them.

The dogs started barking even before they came down into the valley, approaching the small town. It was a cold, clear January night, the wind searing along the unforested loess hills and slipping through the valleys. They had been marching since early that morning, crossing a succession of mountains in single file on narrow trails through the jagged landscape, not daring to stop for more than a quick meal of rice. The railroad tracks ran through here, just beyond the town. After the failure of their earlier attempts, this time seemed more promising. Everything was quiet except for the dogs. There was no shouting, no sound of gunfire, no visible evidence of a Japanese patrol. The moon was not yet up and they carried no lights, so their blue uniforms looked black in the inky darkness. The column moved quickly, silently, the men walking softly on the same worn, felt-soled shoes they had used to cover the hundreds of miles on their way here. They did not talk. They were under orders not to cough.

Carlson did not feel afraid. Rather, he had never felt more alive in his entire life. He breathed deeply in the cold night air, opened his mind to the sounds of the dark town as it came into view. His previous escort, the young regimental commander Chen, had stayed behind with his own forces while a different battalion, led by an officer named Kong, was shepherding them across. Warmed by his heavy, fur-lined coat, Carlson looked to the young battalion commander to find out what would happen next. The Japanese held this town, but there were not enough of them to keep constant patrols in such a vast, inhospitable part of the country. In the stillness that emanated from the town, he could sense that this might be the opening they had been probing for.

Kong indicated silently that it was time. He took Carlson by his hand, gripping it tightly, and together they ran, swiftly and breathlessly, down into the darkened town. Against the symphony of the dogs he could see glimpses of motion — a company of soldiers sent ahead to protect their flank, holding a position at the edge of town as Carlson and the battalion commander ran past. If there were civilians left in the town they did not show themselves — but there was no way to know if one of them had gone off to alert the Japanese, so still, they ran. Then they were through the town, and pushing onward — through the valley, across a small river, up an embankment, and toward the raised railroad crossing. Hand in hand, they ran until it felt safe. Then Kong let go of Carlson, gave a quick salute, and turned back for the rest of his men.

They couldn’t stop there for long, so close to the railroad, so once the entire column of 600 had made the crossing they continued into the mountains again, back onto the loose, rocky paths, with the north star blazing in the sky ahead of them. They climbed again, then descended into a valley, and climbed one last mountain, their eighth peak of the day, and at the top they finally rested. Carlson’s watch said 2 a.m. The men — boys, really, they seemed to him — were exhausted, but no one had been left behind. They sprawled on the ground in weary disarray and went to sleep. They had covered nearly 50 miles on foot since setting out for the railroad crossing the morning before. They had barely eaten, and barely rested, but there were no complaints. They had slipped past the enemy’s line of control without firing a single shot.

Carlson was still awake. A half-moon was beginning to rise on the eastern horizon, revealing the pale, deep yellow outline of distant hills. A billion stars burned above in their sharp intensity as a cold wind sheared across the mountaintop, making him shiver in his coat. Exhausted and enthralled, he looked around him at the boys in their blue jackets sleeping on the ground in the bitter cold, these young would-be defenders of their country, and thought to himself that here, around him, was the foundation for what could be one of the greatest military forces in the world. ∎

Excerpted from The Raider by Stephen R. Platt. Copyright ©2025 by Stephen R. Platt. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

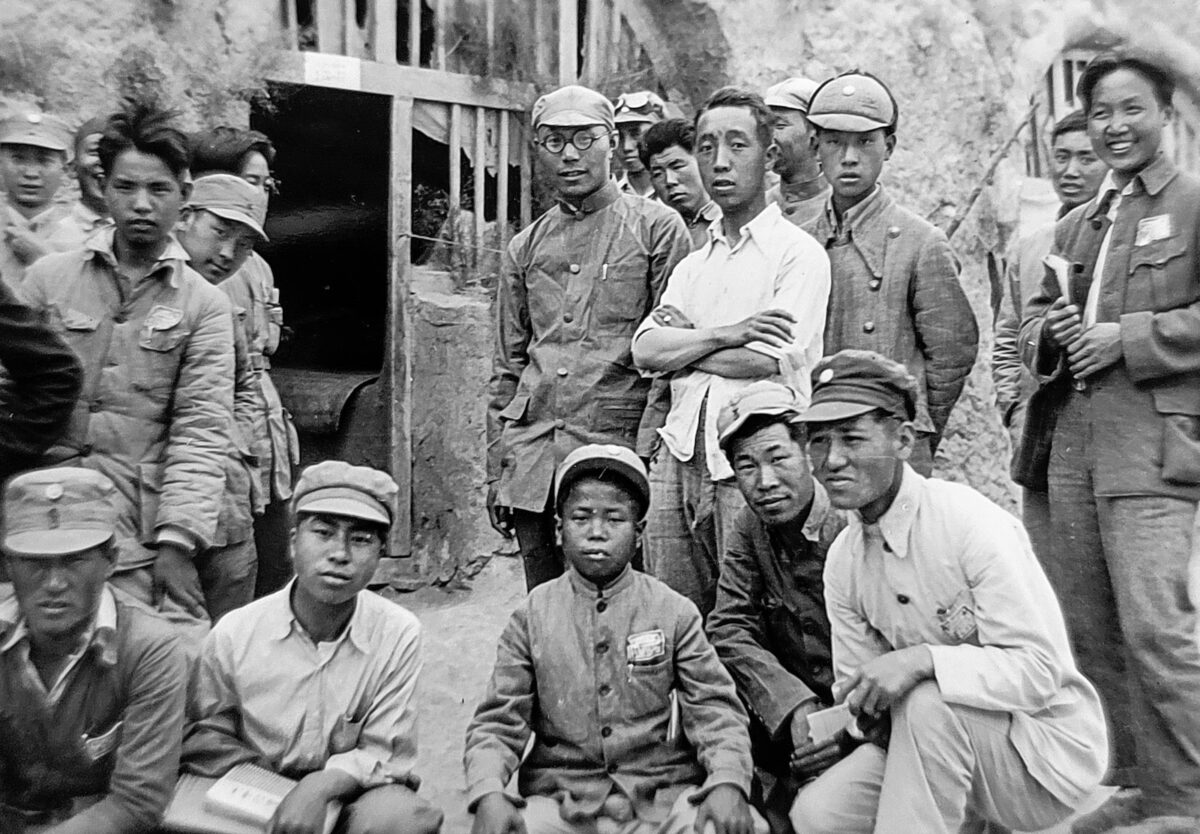

Header: Zhu De with Evans Carlson. (Helen Foster Snow Paper/Brigham Young University)

Stephen R. Platt is an award-winning historian of China and the West. His books include Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom (Knopf, 2012), which won the Cundill History Prize, and Imperial Twilight (Knopf, 2018), shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize. Platt teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and holds a PhD in History from Yale. He lives with his family in Northampton, MA.