Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

Reviewed: Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People, by His Holiness the Dalai Lama (William Morrow, March 2025).

Irrespective of the Tibetan people’s wishes, Beijing will appoint its own 15th Dalai Lama when Tenzin Gyatso, the current and 14th Dalai Lama, passes away.

The conflict over reincarnation and succession is no longer hypothetical. On July 6, Tenzin Gyatso turned 90. He has vehemently rejected China’s interference, arguing that it is inappropriate for an avowedly atheist, communist government to intervene in religious matters. He has even sarcastically suggested that China should first recognize the reincarnations of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping before meddling in the reincarnation of lamas. Nonetheless, until now he has remained circumspect on his plans for the Dalai Lama institution. But in his latest memoir, Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People (William Morrow, March 2025), the 14th Dalai Lama has finally settled the whether and whither of his reincarnation.

In 1969, the Dalai Lama first proposed that if Tibetans believe the institution has fulfilled its purpose, it should end with him. He has repeatedly stated that the continuation of the Dalai Lama’s role rests solely with the Tibetan people and himself. This position underscores his commitment to democratic values and Tibetan self-determination, directly challenging China’s attempts to control the reincarnation process. Now, in Voice for the Voiceless, the Dalai Lama states that he has received “numerous petitions” from Tibetan Buddhist communities asking him to “ensure that the Dalai Lama lineage be continued.” He then declares categorically that his reincarnation “will be born in the free world,” meaning outside China and Tibet. This is a strategic move to ensure that the next Dalai Lama can continue his mission of promoting “universal compassion,” serving as the “spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism” and embodying the “aspirations of the Tibetan people” without interference from the Chinese government.

The 14th Dalai Lama has finally settled the whether and whither of his reincarnation.

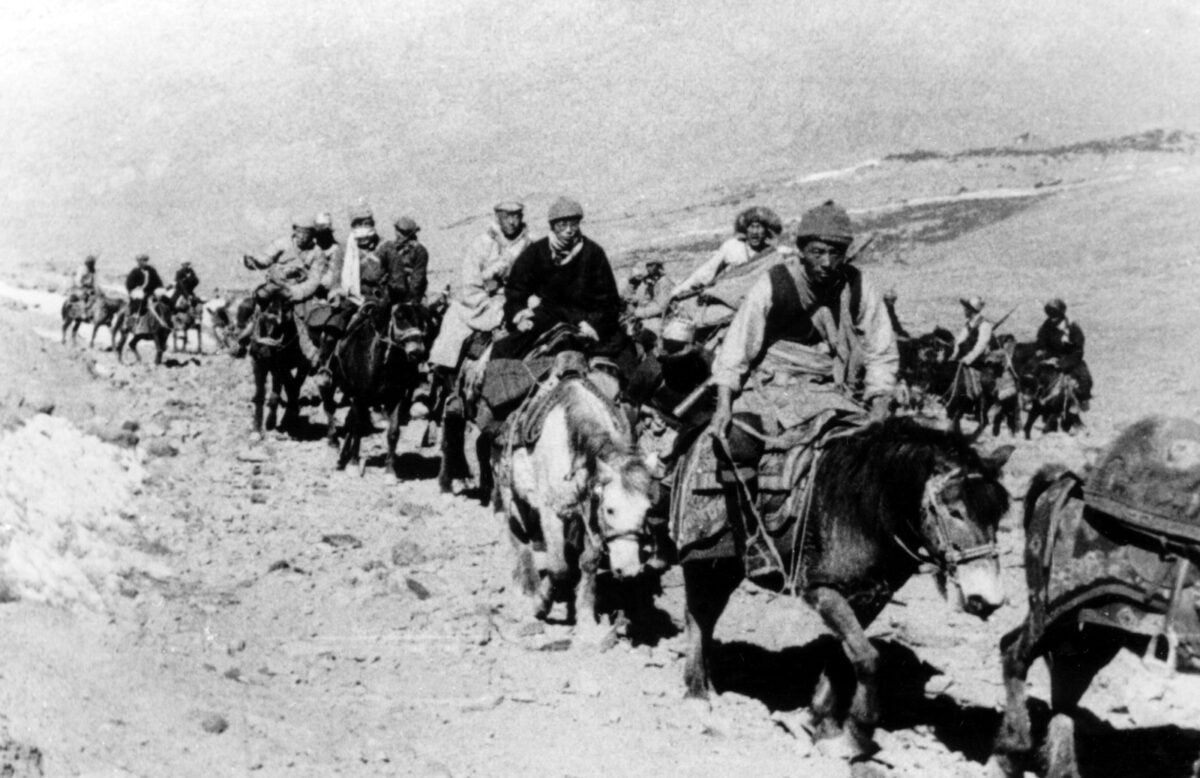

Tibet’s past shows just how fraught succession fights over the Dalai Lama can be. The rule of the Dalai Lama in Tibet (who was previously a purely spiritual role since the 15th century) began in 1637 when Gushri Khan (1582-1655), the leader of the Khoshot Mongols, invaded Tibet. He deposed the secular ruler of Tibet, the Tsangpa King, and installed the 5th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1642–1682), as a symbolic religious leader. Though Gushri Khan then proclaimed himself the King of Tibet (བོད་གྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ་ bod gyi rgyal po), the 5th Dalai Lama slowly consolidated temporal power. He eventually built the system of government known as the Ganden Phodrang, named after his monastic residence at Drepung Monastery, that governed Tibet until 1959 when the current Dalai Lama escaped to India.

After the death of the 5th Dalai Lama, disputes over succession lasted for more than 30 years. In 1720, Kelzang Gyatso from Lithang, in present day Sichuan province, was installed as the 6th Dalai Lama with the backing of Manchu forces in the Qing Dynasty. While the Dalai Lamas became associated with ruling Tibet, only the 5th and 13th Dalai Lamas effectively governed the country. The others either did not reach maturity to assume political power, or that power was ceded to the rule of lama regents.

For Tibetan Buddhists, reincarnation is primarily a religious issue. For China, however, the selection of the next Dalai Lama is a matter of sovereignty. The Chinese state asserts ultimate authority over all matters within its territory, including religion. This mirrors Beijing’s position with the Vatican, as it refuses to recognize any Catholic bishops not appointed by the state. In the case of the Dalai Lama, China leans heavily on historical precedent — particularly the Qing dynasty’s involvement in past selections — to justify its claims of sovereignty over Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism. The Qing claims are based on the Tibetan concept of yon mchod (ཡོན་མཆོད་་), meaning “priest and patron,” where the Qing Emperor was regarded as the principal patron of the Dalai Lamas. Though the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 ended this relationship — which the 13th Dalai Lama had poignantly remarked was “fading like a rainbow in the sky” — Beijing today sees itself in a similar light.

China has announced that it will supervise and approve the next Dalai Lama using the “Golden Urn” method, in which the names of candidates adduced by Tibetan oracles are inscribed on wooden slips and placed in an urn alongside one blank slip. The name drawn from the urn, likely by the head of the state-run Buddhist Association of China’s Tibetan Buddhism division, would be the next Dalai Lama; a blank would render the process void.

In May 1995, the six year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima — selected by the Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lam, the second highest spiritual authority in Tibet — was kidnapped along with his family by the Chinese government. (This story was ably covered in Isabel Hilton’s 2001 book The Search for the Panchen Lama.) In November of that year, Beijing used the “Golden Urn” method to choose an alternate Panchen Lama. The whereabouts of Gedhun Choekyi Nyima remain unknown, while Beijing’s selection of Panchen Lama lives in Beijing rather than the Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse, Tibet, as is traditional.

China has the political machinery to enforce its choice. It can and will proceed with its selection of an alternate 15th Dalai Lama. That figure — much like the state-appointed Panchen Lama — will likely lack legitimacy among Tibetans in exile, as well as many inside Tibet and the international Buddhist community. For many Buddhists, China’s insistence on controlling the succession is perceived as a politicization of Tibetan Buddhism through the installation of a puppet Dalai Lama.

The Dalai Lama has sarcastically suggested that China should first recognize the reincarnations of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping before meddling in the reincarnation of lamas.

Voice for the Voiceless is a significant reminder of the moral and political issues underlying the Tibetan struggle over the last three-quarters of a century, and of the Dalai Lama’s role in this history. The book’s overarching goal is to illuminate potential avenues for resolving these challenges, despite what the Dalai Lama terms the lack of “necessary political will” to do so by the Chinese Communist Party leadership.

Much of the book describes the Dalai Lama’s pursuit of a resolution through what he calls the “Middle Way Approach,” which advocates for “genuine autonomy” for Tibet within China, rather than independence. Inside China, the traditional Tibetan homeland is split between five major administrative regions: the Tibetan Autonomous Region and four provinces (Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan). The Dalai Lama argues for the consolidation of these into one region, to be governed by Tibetans, with limits on further Han migration into the traditional Tibetan homeland, though not the expulsion of those families who have called it their home for decades. He argues that this is a realistic approach to preserving Tibetan culture while maintaining China’s territorial integrity.

Despite the intensity of his conflict with Beijing, in Voice for the Voiceless the Dalai Lama presents various Chinese leaders with considerable nuance. He describes Mao Zedong, whom he met personally, as initially warm and hospitable, though his legacy is later tied to the destructive Cultural Revolution and other repressive policies. The Dalai Lama’s view of Deng Xiaoping, meanwhile, is layered. Deng served as the political commissar of the Southwest Military Region, the force that marched into Tibet in 1951, compelling the signing of the Seventeen-Point Agreement which recognised Chinese sovereignty over an internally autonomous Tibet (and later served as a model for the “One Country, Two Systems” approach proposed for Hong Kong and Taiwan). While acknowledging Deng’s pivotal role in opening China’s economy, the Dalai Lama also critiques Deng’s violent suppression of dissent in 1989.

As for more recent Chinese leaders, although the Dalai Lama has not met them in person, he has observed them closely. Particular attention is paid to Xi Jinping. The Dalai Lama had a positive relationship with Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, one of the more liberal leaders in the Communist Party. The elder Xi had a warm and affable demeanor, and during the Dalai Lama’s 1954–1955 visit to Beijing, the two established a genuine rapport. Xi Zhongxun’s home regularly received Tibetan visitors, and he maintained close ties with the Panchen Lama’s family. Xi’s son, Xi Jinping, also had Tibetan schoolmates and appeared familiar with the Tibet issue. These personal connections gave the Dalai Lama hope that Xi Jinping would bring empathy and understanding to Tibet policy.

We learn from the book that in 2014, when it was announced that Xi would be making a state visit to India, the Dalai Lama expressed a desire to meet with him, but, as he puts it, “nothing came of this gesture.” We now know that although the Chinese side reportedly indicated openness to the idea, the Indian government, concerned about overshadowing the first meeting between Xi and newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi, had not allowed it to proceed. The attitude of the Indian government, which plays host to the Tibetan government in exile at Dharmsala, is often a less-discussed variable in the Dalai Lama’s succession. Yet as the Dalai Lama notes repeatedly in the memoir, he has long been treated with great respect, provided high-level security and privileges as an honored guest of the Indian government.

The question remains: will the next reincarnation of the Dalai Lama receive the same status, or will India treat him as a private citizen? Much will depend on India’s geopolitical calculus, and its decision will significantly influence the global stature and legitimacy of the 15th Dalai Lama. India has often practiced a policy of strategic ambiguity when it comes to Tibetan issues, including the succession issue. After the Dalai Lama announced that he would indeed reincarnate, the Indian Ministry of External Affairs released a statement affirming India’s respect for freedom of religion, without making any explicit reference to the next Dalai Lama. This contrasted Indian Minister Kiren Rijiju’s remarks at the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday celebration in Dharamsala, where he expressed support for the Dalai Lama’s decision: “Nobody else has the right to decide it except him and the conventions in place.”

On July 6, Tenzin Gyatso’s birthday, Prime Minister Modi wrote that the Dalai Lama has been an “enduring symbol of love, compassion, patience and moral discipline.” Modi finished his felicitations by praying for the “continued good health and long life” of the Dalai Lama — a touching message, to be sure, but a cynic might read into it Modi’s desire to delay the inevitable geopolitical storm that will follow the Dalai Lama’s passing.

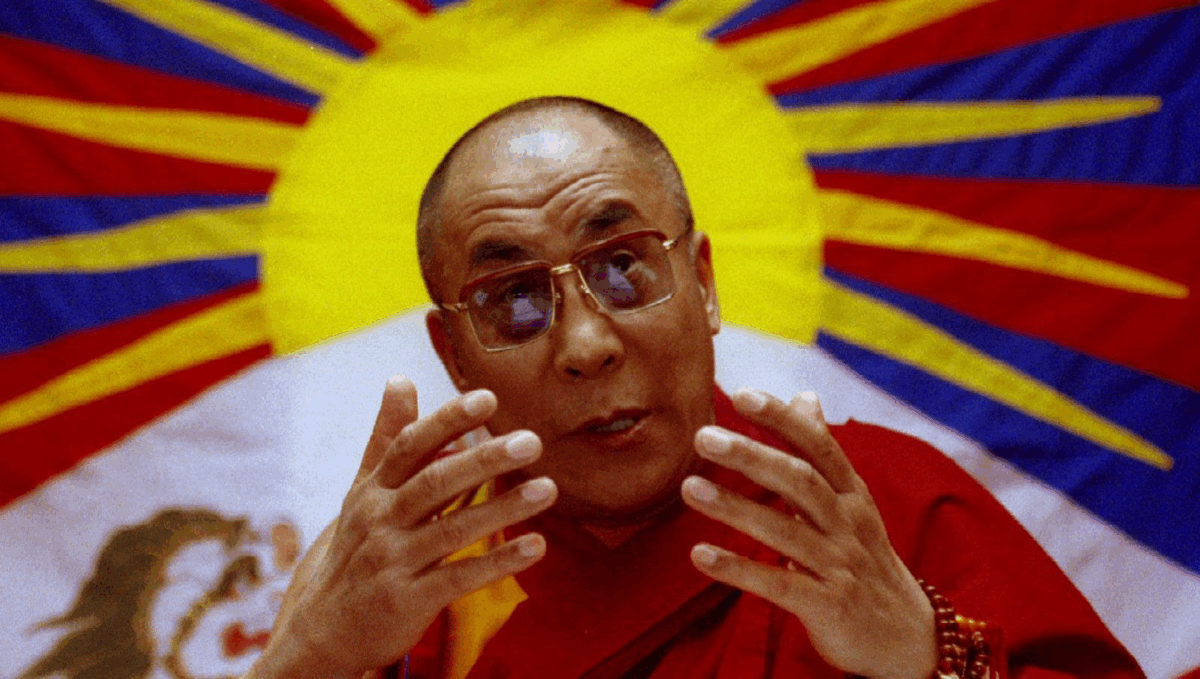

The Dalai Lama’s personal reflections in Voice for the Voiceless — on suffering, resilience and compassion — add an emotional depth that will help readers who face adversity in their own lives. First and foremost a Buddhist monk, his beliefs are deeply rooted in the principles of Buddhism. He emphasizes the importance of cultivating compassion and is dedicated to preserving Tibet’s unique Buddhist tradition. Warning of the ongoing erosion of Tibetan identity, and calling for the protection of Tibetan language, culture and religion, the book is directed both to the Chinese people and the global community, urging empathy for the struggles and abuses experienced by the Tibetan people.

The very title of the book, an echo of the Czech dissident (and future president) Václav Havel’s 1978 essay The Power of the Powerless, is an apt reference given Havel’s close friendship with, and admiration for, the Dalai Lama. Perhaps it will become doubly apt if, like Havel, the next Dalai Lama will come to lead in the homeland where he was once repressed. ∎

Header: The Dalai Lama celebrates his upcoming 90th birthday at Tsuglagkhang, the Dalai Lama Temple, on July 5, 2025, in Dharamsala, India. (Elke Scholiers/Getty Images)

Tsering Shakya is a historian of Tibet and a scholar on Tibetan literature. He is the author of The Dragon in the Land of the Snows (2000) and numerous other works. His writings and commentary have been featured in Time and New Left Review. Born in Lhasa, he is Associate Professor in the Department of Asian Studies & School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.