A plagiarism scandal is rocking China’s literary scene these days. An anonymous RedNote account has exposed big name authors for lifting passages from foreign novelists. The implicated writers run the gamut — a children’s books author, a rising star, veteran practitioners of “pure literature” — with one thing in common: ties to China’s literary establishment. The posts, originally a grassroots effort to defend literary integrity, have become an existential crisis for the tight-knit circle of writers, editors and reviewers affiliated with state-subsidized journals.

This reckoning may partly explain the recent popularity of “amateur writing” (素人写作). A crop of writers with little or no formal training, many of whom hold day jobs far removed from clubby literary circles, have begun topping best seller lists. Much like the 1990s memoir boom in the U.S., this wave has been embraced by readers who feel drawn to stories that feel grounded, urgent, and real. In this edition of the “What China’s Reading” column, we spotlight five titles from this vibrant and growing scene. One follows a mother as she confronts her troubled past while raising an autistic daughter. Another traces a young Italian man’s kaleidoscopic experiences of living in China, which he wrote in Chinese. We’ve also included titles by three prolific late bloomers, one of whom didn’t publish until her seventies. Millions of readers have found something true in these voices. We hope you will, too.

Little Tree

小树

Zhu Maomao never imagined becoming a mother; not with her bipolar disorder and family history of mental illness. But a trip to her husband’s hometown and an unexpected pregnancy changed her mind. She was filled with hope when she gave birth to her daughter, whom she named Little Tree (树儿). At age five, Little Tree was diagnosed with mild autism. From that moment on, Zhu’s life became a series of urgent questions: Would a public school or a specialized school better serve her daughter? How should she connect with Little Tree? What kind of future could she hope for? To find answers, Zhu accompanied her daughter through first grade at a public school that placed neurotypical children and children with disabilities in the same classroom, befriending her daughter’s classmates and their parents. This memoir of her experiences is candid, moving and often funny, tracing a mother’s path as she confronts the imperfections she sees in her child — and in herself.

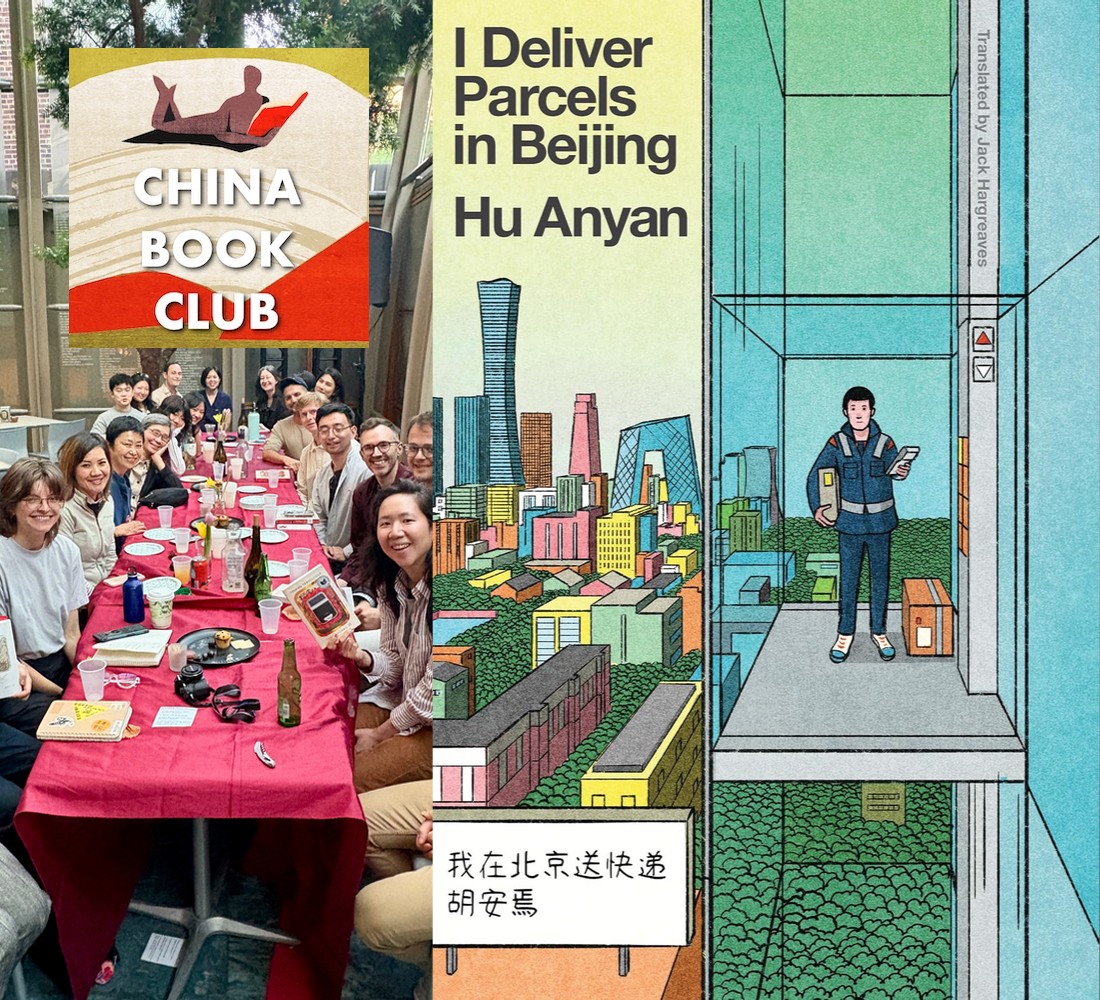

The One Who Chases Time

赶时间的人

Wang Jibin discovered literature at 19 years old, while working on a construction crew far from home. When his budding interest in writing met with disapproval from those closest to him, he kept at it in secret, taking on jobs from hauling sand to running a grocery store. In 2018 he stumbled into gig work, delivering parcels and takeout. Since then, Wang has covered more than 150,000 kilometers in Quanzhou and written over 3,000 poems during his breaks, leading to the publication of this poetry collection in 2023. Like a calloused hand, Wang’s poems are unadorned, restrained and powerful. He writes of hardship and the quiet sorrows of the have-nots: farmers, nannies, cleaners and fellow migrant workers. Some of the strongest poems in the collection startle with their defiant originality. In one, Wang enters a newly built temple, where someone has ordered takeout. Standing before the Buddha statues, he writes: “But I’m not going to kneel down and pray. / Time is pressing me on. / I have many takeouts to deliver punctually. / Right now, I’m the Buddha / faced with numerous worshipers.” (可我并不准备跪拜/时间在催/我还有许多单子需要及时配送/此刻,我才是菩萨/面对众多的许愿人)

Bean and Sesame Tea

豆子芝麻茶

Yang Benfen was 62 when she lost her mother. After the funeral, sitting alone in the kitchen, she felt an overwhelming urge to write down her mother’s story. That impulse became Autumn Garden, her first memoir, published in 2020 to widespread acclaim. The book won more than a dozen literary awards and launched Yang into an unexpected and prolific writing career. Since then, she has published two more books chronicling life in a Jiangxi village and her own marriage. In this, her fourth and most recent work, Yang shifts her focus to the women around her — a neighbor, an old classmate, a former coworker — who shared their life stories with her generously. These are tales of surviving childhood abuse, human trafficking and marital rape but also of reclaiming one’s life through self-education, agency and resilience. Named after a simple, nourishing drink from Yang’s native Hunan province, Bean and Sesame Tea is a memoir-in-essays that leaves you grounded and strengthened.

Tiny Dust

微尘

To reach mineral veins buried deep in the mountains, blasting specialists obliterate rock with explosives. For 16 years, Chen Nianxi was a blaster laboring in gold, iron and zinc mines across China. Underground in the dark and dust, he jotted down poems and stories whenever he could. After his first poetry collection, Record of Demolition, found an audience, Chen began writing prose. In this essay collection, he looks back on the people he met and the places he worked, giving readers a glimpse into the world of mining and those who depend on it. Chen retired in 2015 after suffering a neck injury on the job that required surgery. Before going under, he was asked whether he’d prefer an implant of domestic or imported metal. He couldn’t help but wonder: had he once helped unearth the metal plate in his neck? His writing, like the minerals he once extracted, comes from deep below the surface.

I Had A Dream in Chinese

我用中文做了场梦

In 2016, Alessandro Ceschi, a media studies graduate from Italy, arrived in Beijing looking for new opportunities. What started as a normal Westerner-in-China journey (making friends with the help of baijiu and Pleco, learning Mandarin by watching Chinese dramas, posing as Mark Zuckerberg in a student project) took an unexpected turn when he began hosting a Chinese-language writing salon in his apartment in Shanghai. Ceschi is not the first foreigner to write about China, but what sets this essay collection apart is that it’s written in Chinese. This choice adds a layer of narrative distance — he sometimes refers to himself in the third person as “Ya Li,” a phonetic version of his first name. Unpretentious and witty, his writing captures moments of connection, culture shock and quiet loneliness. Whether describing the pecking order of language teachers at his school or reflecting on life under China’s Covid policies, Ceschi’s essays offer a fresh, engaging perspective for anyone curious about life between languages. ∎

Hailing from Chengdu, Na Zhong is a New York-based fiction writer and literary translator. Her work has appeared in Guernica, A Public Space, Lit Hub and others. She co-founded the bilingual creative community, Accent Society, and co-hosts the Mandarin literary podcast 跳岛FM. Na is a 2021-2022 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, and a 2023 MacDowell Fellow.