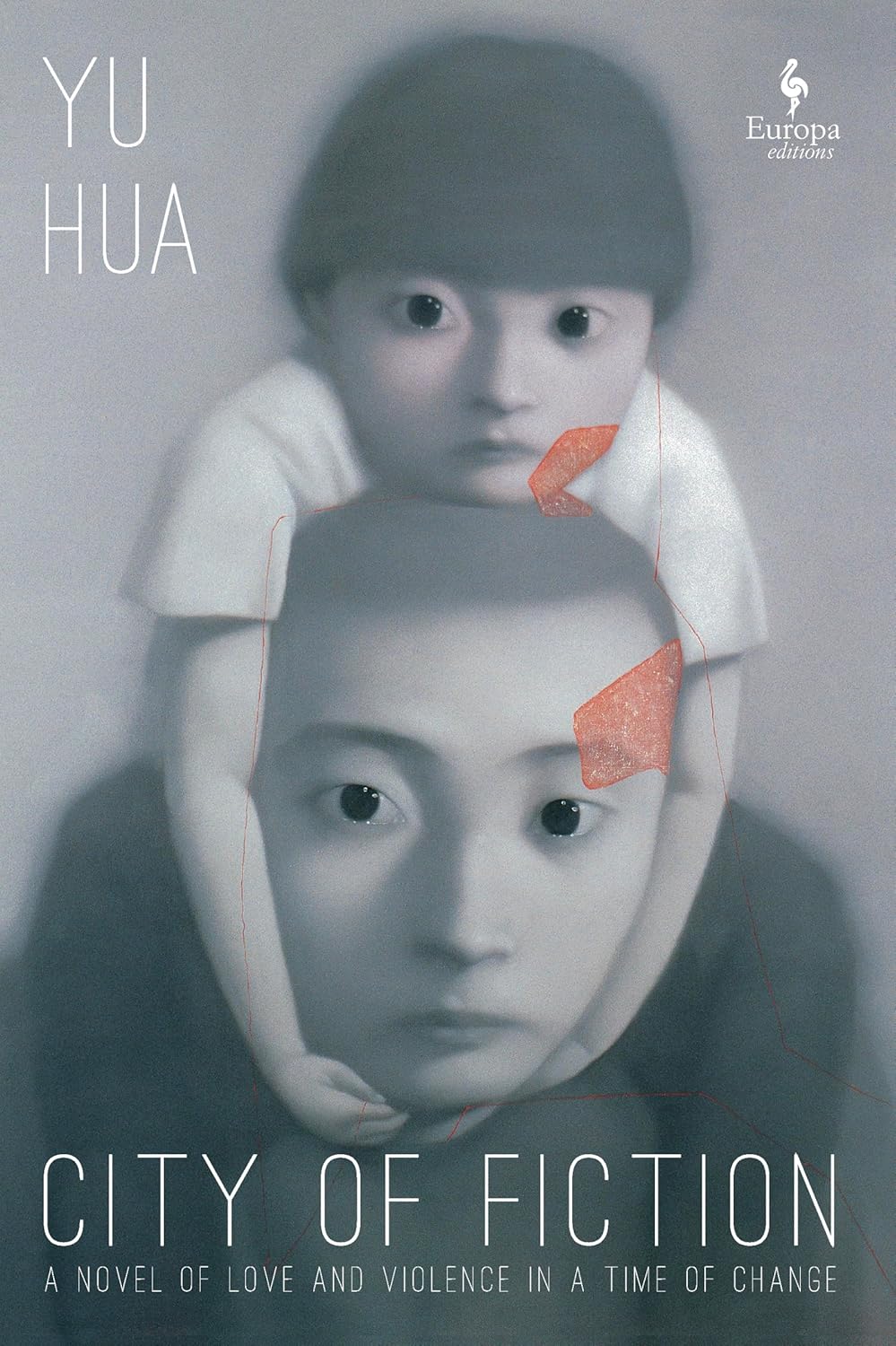

Reviewed: City of Fiction by Yu Hua, tr. Todd Foley (Europa Editions, April 2025).

A sense of foreboding suffuses Yu Hua’s (余华) latest novel in translation, City of Fiction. First published in China in 2021, the original title Wencheng (文城) is perhaps more literally “city of letters,” though the power of imagination is a core theme of the book. Set in the early 20th century, the novel opens on a wealthy woodworker, Lin Xiangfu, and recalls his search 17 years earlier for his missing wife. Having survived a perilous journey from the north, Lin carries his infant daughter through the snow and cold into homes where he hears babies crying. Offering coppers to the breastfeeding women, he pleads: “Please, take pity on my daughter — give her a few drinks of milk.”

Because so many families nursed his daughter, Lin Xiangfu names the child Lin Baijia, “Hundred-Homes Lin.” The mystery of the girl’s birth mother drives the narrative. We learn that Lin was a wealthy young landowner who took in two travelers claiming to be siblings: Aqiang and his sister Xiaomei. Lin and Xiaomei fall in love and wed, but she runs off with seven bars of gold — nearly half his family’s generational wealth. She returns pregnant with Lin’s child, but after the baby’s birth she disappears again.

Lin Xiangfu sets off in search of his missing wife, seeking the city of Wencheng, where Aqiang claimed he was from. But he comes to realize that “Aqiang’s Wencheng wasn’t real, and that, in all likelihood, neither were the names Aqiang and Xiaomei.” Initially travelling to several cities, Lin learns from locals that Wencheng is fictional. Still determined to find Xiaomei, he returns to the southern town of Xizhen (“stream town”) where the residents speak her dialect. Moving in with the family of a carpenter, Chen Yongliang, he lives out the remainder of his life in Xizhen.

Told by a third-person narrator, the novel has two parts. The first focuses on Lin Xiangfu’s story; the second on Xiaomei’s. Together, they offer a richly textured story that spans the end of the Qing Dynasty and the chaotic warlord period that followed the founding of the Republic of China in 1912. Yu Hua describes the torture wreaked by gangs of roving bandits. Full of gratuitous and often graphic violence, these passages pummel the reader with cruelty and gore:

When the bandits arrived, they butchered everyone they saw. The villagers scrambled, running for their lives. The women who saw their children fall under the initial gunshots rushed over to them, while One-Ax Zhang came over and chopped the women down with wild swings of his ax, and the other bandits cut them with their swords. Blood spurted everywhere, filling the air with its stench. The women running behind saw the women in front get their shoulders, arms, and heads get chopped off, yet they continued running thoughtlessly toward their children. One woman came running up holding a child, and One-Ax Zhang whacked off its head. Blood sprayed all over the woman’s face, but she seemed completely unaware and continued running, clutching her headless child as if they were escaping unscathed out through the village gate.

The preponderance of such passages make us appreciate the glimpses of humanity elsewhere in the novel, but such foregrounding of brutality may dismay a sensitive reader.

City of Fiction is a mostly realist novel, but it is punctuated by moments of magic realism. Stabbed in the ear, a dagger in his brain, Lin Xiangfu dies but stands fast:

Although he was now dead, Lin Xiangfu was still standing, his body trussed up and looking like a mountainside cliff, the dagger still sticking out of his ear as his head slowly began tilting to the left. His slightly opened mouth and squinting eyes made it look as if her (sic) were smiling. Right before the last flicker of life left his body, he saw an image of his daughter—Lin Baijia, an orange flower embroidered on her lapel, was walking toward him down a hallway in the McTyreire School.

The bandits in the room fell silent. They looked at Lin Xiangfu in shock, wondering why he hadn’t fallen over. After a few moments, one of the bandits said to the others,

“Fuck—he’s smiling.”

His smile spooks the bandits who murdered him. His dying thoughts drive home the power of memory, and by extension the power of narrative and fiction — major themes in the novel. Yet the text also underscores the fallibility of memory and storytelling in the midst of chaos. Memories often surface on boats, where flashbacks help tie together the book’s disparate narrative threads. When a village boatman returns Lin’s corpse to Xizhen, he becomes confused when asked what happened. Ignoring the question about the corpse, he instead displays his own hand, which is missing a finger, and recounts its loss in a battle years ago. This incident instantiates the novel’s nonlinear narrative, as well as the plasticity of fiction, a theme brought out by the English translation of the title.

Yu Hua describes the torture wreaked by gangs of roving bandits. Full of gratuitous and often graphic violence, these passages pummel the reader with cruelty and gore.

Yu Hua’s importance as a writer cannot be overstated. City of Fiction is his sixth novel, and he has also published 11 collections of short stories and six essay collections. Vivid, memorable and full of humor, his novels rank among the most powerful and bestselling of contemporary Chinese fiction. Earthy direct speech brings Yu Hua’s characters to life, and strong narrative arcs make his best novels page-turners. These works capture the everyday heroism of the characters’ tenacity in the face of war, poverty, corruption and political chaos.

Now translated into 45 languages, Yu Hua’s engrossing fiction has garnered attention since his first experimental stories of the 1980s. With these stories, he made his mark as one of the top avant-garde writers, drawing on techniques of modernism (Kafka, Borges and Kawabata were influences). To reject Mao-era revolutionary realism and romanticism, Yu and his cohort wrote surreal fiction. His phantasmagoric stories generally avoided direct mention of politics, but they performed political work. His modernist techniques defied socialist prescriptions for literature in the service of politics, and the stories’ raw, senseless violence helped to purge the collective trauma of China’s recent past. The 1987 story “On the Road at Eighteen” (十八岁出门远行), a coming-of-age tale that culminates in beatings, shot Yu to fame, and was followed by further allegories for the persecutions of the Cultural Revolution.

After the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, Yu Hua turned from avant-garde experimentation to brave social responsibility. For his first novel, Cries in the Drizzle (在细雨中的呼喊, 1991, tr. Allan H. Barr 2007), he used literary language with little dialogue. The novel describes rural life during the Mao era as observed by a lonely boy outcast by his family and village. Despite its virtues, the book may have sold less well because of its elevated register, disjointed storyline and emotional detachment.

Yu Hua honed a more unadorned language that would become his trademark in To Live (活着, 1992, tr. Michael Berry 2003). This novel presents a self-deprecating peasant’s frank account of his life, spanning the key periods of China’s modern history, as told to a young narrator from the city. A story of war, rural poverty and murderous political programs, the interludes in the narrative’s present allow leaps in time and a swift tempo despite the novel’s epic sweep. As the protagonist recounts losing everyone and everything he holds dear, wry humor tempers the unremitting tragedy. The book was a huge success, selling more than 10 million copies since publication and still topping bestseller lists in China today, as well as becoming a 1994 film directed by Zhang Yimou.

The simple language and economy of detail that grace To Live continued with Chronicle of a Blood Merchant (许三观卖血记, 1995, tr. Andrew F. Jones 2004), the compelling story of a man who sells blood to obtain a wife, support his family and eventually save the life of his wife’s son. The novel deftly combines the symbolic uses of blood, from the sacrifice of virgin blood to the notion of blood ties and the sanctity of lifeblood. As the protagonist gambles with his life, he wins insofar as he survives. But the apparently happy ending subversively hints at the ethical conundrums of market capitalism.

Yu Hua’s next novel, the tragicomedy Brothers (兄弟, 2005/2006, tr. Eileen Chow and Carlos Rojas 2010), chronicles the lives of two stepbrothers as teenagers during the Cultural Revolution and as adults in the reform era that followed. From a scene in which Red Guards beat the brothers’ father to death, to a “National Virgin Beauty Competition,” the plot’s absurdity probes the moral depravity of both authoritarianism and turbo-consumerism. The 600-page novel, published in two parts, quickly sold more than a million copies. Yu’s range expanded further as he returned to magic realism with The Seventh Day (第七天, 2013, tr. Allan H. Barr 2016), a surreal account of a dead man roaming the afterworld.

In City of Fiction, translated by Todd Foley, Yu Hua finds an altogether different register from his previous work. In To Live, the suffering of the protagonist feels pared-down and stoic. Yet the violence in his latest novel is neither subdued nor restrained, but mind-numbing in its sheer excess. It is gratuitous, relentless, often graphic and at times cartoonish, with squirting blood, penetrated orifices and severed ears. Along with his early stories, this latest novel marks the extreme end of Yu Hua’s hallmark visceral violence, and extends the lineage of post-Mao Chinese fiction focused on cruelty.

Along with other contemporary Chinese works with such graphic violence, Yu’s novel does political work by purging the traumas of China’s bloody 20th century.

One explanation for the foregrounded violence in City of Fiction is that the novel follows in the tradition of Chinese “bandit literature” (土匪文学) — a traditional genre which spotlights warlords, outlaws and the violence of unsettled eras. In bandit literature, violence is front-and-center, often gratuitous and sensational in its depiction of kidnapping, mutilation, gang rape and slaughter. Rather than punctuate the story, the violence often defines the texture of the narrative.

The most famous antecedent is The Water Margin (水浒传, c.1450), a Ming Dynasty masterpiece about a hard-drinking gang of 108 bandits who are merciless in their sadism, misogyny and lust for revenge. Yet the brotherhood frequently acts out of loyalty and in the name of righteousness; they steal from the rich, defeat government corruption and ultimately defend the Song Dynasty. The best of bandit literature allows some limited sense that good begets good, and evil begets evil (善有善报, 恶有恶报).

In City of Fiction, however, the relentless violence leaves little hope for good. One of the bandits, The Monk, saves the carpenter Chen Yongliang’s son by carrying his unconscious body to his own mother’s home, where she watches over and feeds him. This act of mercy later leads the Chens to join forces with The Monk’s group of “good bandits”:

“‘Becoming a bandit in these troubled times is perfectly understandable,’ said Chen Yongliang, ‘as long as you’re a bandit with a kind heart.’”

By and large, the overwhelming brutality described in the novel only seems to show the inevitability of suffering and evil. Yet along with other contemporary Chinese works with such graphic violence, Yu’s novel does political work by purging the traumas of China’s bloody 20th century, including the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Great Famine, the Cultural Revolution and other topics that can be addressed only indirectly.

Another giant of Chinese literature, the Nobel Laureate Mo Yan (莫言), has also performed this delicate balancing act — exhuming traumatic collective memories while remaining in the grey zone that permits publication. In many of his works, brutality and lust saturate everyday life. Red Sorghum (红高粱家族, 1987) depicts bandits, guerrillas and warlord violence during the Second Sino-Japanese War, although here the suffering holds value insofar as the war was seen as righteous. Mo’s masterpiece Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out (生死疲劳, 2006) features grotesque, over-the-top violence in an epic historical sweep that includes scenes from the Cultural Revolution.

Other Chinese novelists have also made violence central to their works. Su Tong’s (苏童) Rice (米, 1991), a landmark in Chinese literature for its themes of decadence and self-determination, is suffused with nihilism, sexual violence and physical brutality. Violence also runs through Yan Lianke’s (阎连科) novels, which center on trauma, brutality and human lives deformed through structural violence, from the sexual coercion of Serve the People! (为人民服务, 2005) and the bodily exploitation of Dream of Ding Village (丁庄梦, 2006) to the beatings, rapes and mass suicide of The Day the Sun Died (日熄, 2015).

Both parts of City of Fiction contain abrupt endings of lives and storylines. Though Xiaomei’s story offers her some measure of agency, women in the novel are mostly disempowered. Many of the characters feel two-dimensional, and the language at times falls flat. Multiple long passages full of details and lists seem to portend a Chekhov’s gun but turn out to be red herrings. For example, when Lin Xiangfu studies woodworking with master craftsmen, the text catalogues the many styles of carpentry. Yet these details go nowhere. In an essay about the novel, the translator, Todd Foley, excuses “Yu Hua’s inclusion of tedious historical details,” because it “points toward a deeper structure of society.” These minutiae do limn certain aspects of Chinese culture, but the numbing detail does not clearly delineate social structure.

The novel ultimately offers some closure, but little solace. The reader comes to understand the title, as well as the endurance of the central characters’ love, kindness and loyalty. The city of Wencheng is not only fictional, but a city constructed of memory and narratives. As Aqiang suggests to Xiaomei when Lin Xiangfu initially departs from Xizhen (where they had been hiding all along), not only does Wencheng not exist, but it is an eternal place of writing, narrative and fiction:

“The further he goes the further away he’ll get, searching for Wencheng.”

When Aqiang mentioned Wencheng, Xiaomei couldn’t help but ask: “Where is Wencheng?”

“There will always be a place called Wencheng,” Aqiang said.

This imaginary Wencheng had become an ache at the bottom of Xiaomei’s heart. Wencheng meant that Lin Xiangfu and her daughter would never stop wandering and searching. ∎

Header: Yu Hua at the 2009 Turin International Book Fair. (Massimo Di Nonno/Getty)

Sabina Knight is Professor Emerita of Chinese and World Literatures at Smith College. She is the author of The Heart of Time: Moral Agency in Twentieth-Century Chinese Fiction (2006) and Chinese Literature: A Very Short Introduction (2012).

Join our upcoming book club to discuss City of Fiction by Yu Hua with the China Books Review editors (November 5 at Asia Society in New York; November 10 at JF Books in Washington, D.C.). Email us at info[at]chinabooksreview.com to save your seat now!