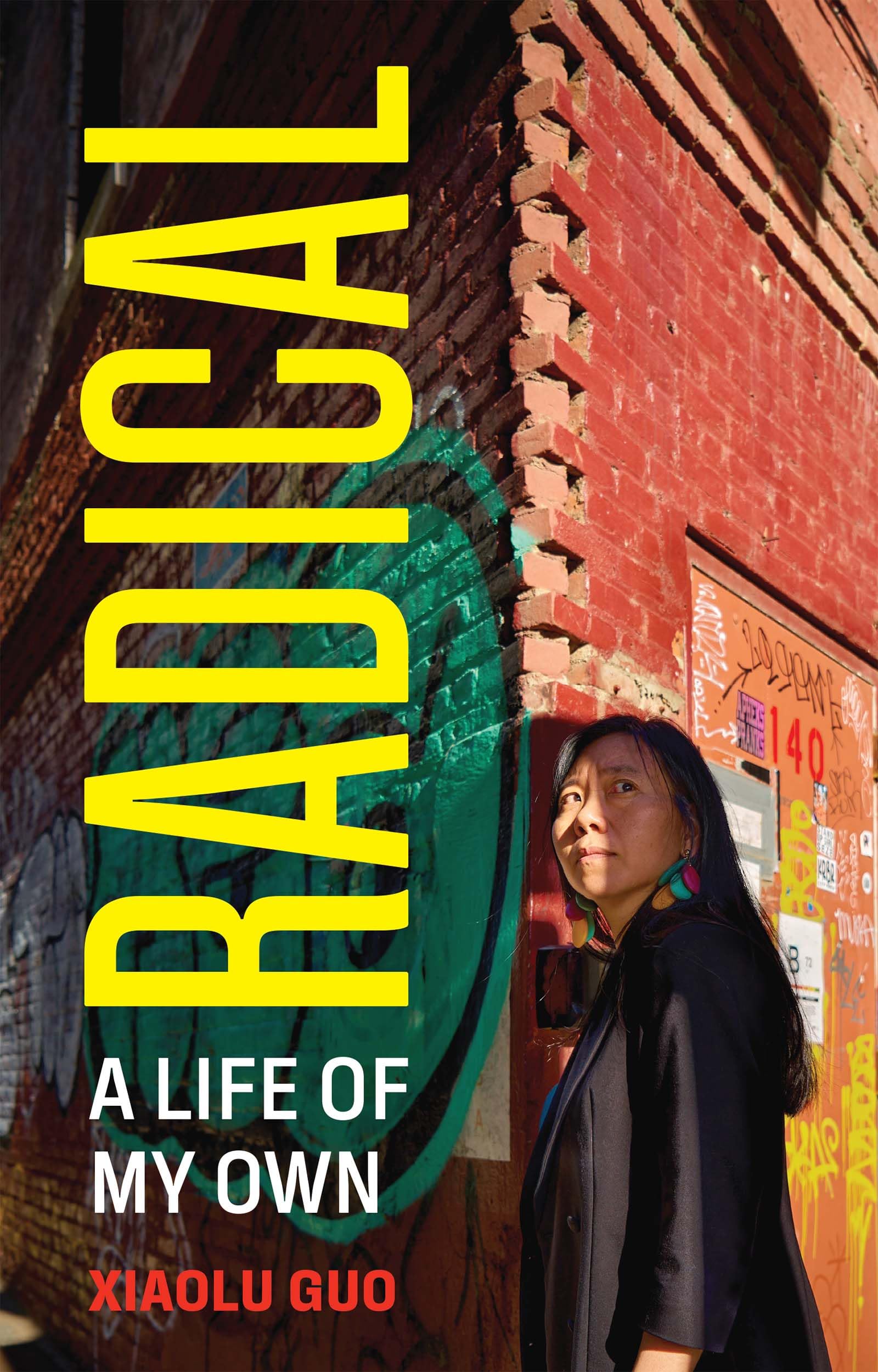

Editor’s note: Novelist Xiaolu Guo grew up in a fishing village in Zhejiang province, studied in Beijing, then left China for London in 2002. In 2018 she moved to New York for a year-long visiting professorship. In Radical: A Life of My Own, her new memoir excerpted here, she traces the fragmented reflections and refracted impressions of her first months exploring the city.

Writing systems in the West use alphabets. The Chinese language uses pictograms and ideograms. Alphabets are codes for sounds. Pictograms depict objects and impressions. The West writes symbolically, the Chinese writes visually.

Our Chinese ideograms are made up of bushou. Bushou can be translated as ‘radical’, meaning ‘root’ in Latin. But when you look at the word bushou it literally means parts and heads. Bushou are the organs of the bodies, through which we write. For example, 山 is the radical for mountain. If you put a man beside a mountain, it becomes a sage: 仙. And if you add the water symbol by the mountain, it becomes a dune: 汕. Our radicals are the parts and heads of the Chinese characters.

In English, ‘radical’ can be a noun or an adjective. It has other meanings: departure from tradition, or advocating great reforms. In Chinese that’s a different word. It’s jijin – 激进. Jijin has nothing to do with roots. It has to do with water rushing forward, just as progressive thinking bursts forth into the future.

In my mind ‘radical’ and ‘bushou’ are intertwined, they criss-cross. For me, many words are like this: the Chinese merges with the English. My linguistic life is a journey through this forest of entanglement, looking for a path. Many of the trees and plants in the forest are deeply familiar to me, others I have never climbed or touched. But no matter where I explore, I always want to keep contact with my roots, with my bushou, even when I find myself in an unknown wordscape.

I walked towards the Empire State Building in Midtown. Close to it but still on 32nd or 34th Street, I discovered that the edifice had disappeared. I raised my chin to the sky, spinning like a levitating top, but I couldn’t locate the spire. The buildings I could see were equally immense, with art deco facades. They encircled me in every direction. I knew I was only eighty or a hundred metres away from the Empire State Building but I had lost all sense of orientation.

Once you get close to something, it disappears. It’s like the idea of searching for ancient Japan after arriving at Tokyo airport, or trying to locate an idyllic village hidden at the foot of a Basque mountain. It does not belong to reality. The Empire State Building appears to exist only in thin air, in the ever expanding distance. It is more an idea than a material thing. The closer you get, the further away it feels.

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates describes a group of people who have lived in a cave all their lives. These people watch shadows projected on the wall and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality but are not the real world. Only those who are freed from the cave will realise that the cave is a prison with dancing shadows, and these people (such as philosophers) will come to understand that the shadows on the wall are not reality at all.

To understand that the Empire State Building is unreal means you have to get out from that reality – American reality. It is like Plato’s Cave. The deeper you enter into the cave, the further away you are from life itself.

In Brooklyn, I passed an enormous brownstone building, infinitely grand and imposing. I decided to turn back, to find out more. Standing in front of the gate, I tried to decipher an engraved plate with faint print on it. I made out that in 1846 Walt Whitman had worked here as a journalist, until he was sacked for his anti-slavery opinions.

So this is the Brooklyn Eagle building, where a daily newspaper was published from 1841 to 1955. What a historic place, set right next to the thunderous long stretch of Brooklyn Bridge. The river shimmered silver blue, just as Whitman might have seen it.

On the way home, I found a bookshop and bought a copy of Leaves of Grass. I already had two or three Chinese translations at home. These Chinese editions have lain around in my different homes in different countries, all these years. But this was my first English copy.

It was my father’s generation that read Walt Whitman in Chinese. My father and my teachers told me to look at the shapes and colours of leaves. But I noticed leaves without having to read the book. Now I was in America, the country of Whitman.So, I opened the pages of Leaves of Grass. Suddenly, I found myself struck by a kind of amnesia. The words before me generated none of the feelings I associated with the Chinese edition I had read long ago. So this is the real Whitman? And I am reading it in the real place, where it was written. My old Whitman fell away from me. I read:

Houses and rooms are full of perfumes . . . . the shelves are crowded with perfumes.

The atmosphere is not a perfume . . . . it has no taste of the distillations . . . . it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever . . . . I am in love with it

The real Whitman is full of ellipses. I wondered about them. Were they just the product of his mind rushing forward while his hands struggled to keep up with getting down his impressions? Or were the gaps between his phrases part of the poetry itself? They might be a form of eloquence, as in when a sage stops speaking to allow his silence to talk. To me they seemed like the white spaces in a Chinese traditional painting, which are also part of the pictorial language.

Flipping through the book, I looked for the publication date. No, the printing date. It didn’t tell me. It’s a Penguin edition of Leaves of Grass, that’s it. It is a first edition. The book first appeared in 1855. He self-published it. No one was waiting to read it. It wasn’t about to be stacked in the important bookshops. It was a poem to himself.

After a few hours of reading Whitman, the sky was the colour of an oyster. It was raining. I forgot that in America they also have rain, just like in England. The Hudson River was still beneath me. It had not emigrated. And it was calling me. I looked at it. It was too far for me to jump in.

No matter where I explore, I always want to keep contact with my roots, even when I find myself in an unknown wordscape

I kept on sneezing violently, as I walked through the streets of Harlem, where I now lived. I imagined I looked red-eyed, and viper-like. Asthma, they said, was much more common in this area than in other parts of New York City.

A high-pitched ringing sound vibrated around the gigantic housing project – General Grant Houses. Was it from a smoke detector, or a fire alarm? As far as I could make out, this piercing sound had been going on since the day I arrived in the neighbourhood. The buildings along 125th Street seemed to be perpetually drenched in it. How did people survive in this din? Or were they so used to it that they could not hear it any more above their own tinnitus?

There was a little statue of an angel, dim and feeble-looking, standing in a fenced yard by 128th Street. That was the place I often stopped and pondered. I remembered reading that James Baldwin went to a primary school on this street. But now the school was gone. Only the angel in the yard remained. I would stare at it through the fence for a long time. There were some plastic flowers in pots around him. It was an alien sight to me.

Angels do not exist in China. Fairies don’t need wings. And China is very far away.

In Central Park, I found myself lost in a maze of woods. I had been coming to the park almost every day, but I hadn’t been to this place yet. Where was I? The trees were tall and serene, surrounding me as if I were in some Scandinavian forest. Looking at their branches and leaves, their names slowly came into my mind. Oak, pine, cherry, hackberry. There was an impressive old tree, its spidery roots sprawling under my boots. A tag was attached to the trunk: American sycamore. Planted in 1859 during the construction of the Reservoir.

It is more than 150 years old, I thought. It looked to me just like an ordinary tree you would find in any part of London, or along the roadside in Beijing. Though the canopy looked wider and thicker, and its bark more silver.

I wandered farther, passing over a rusty little bridge. The air smelled of hay. It was not the typical air of the city. It was quiet and peaceful here – birdsong replaced the sound of Manhattan traffic. Somewhere above my head I heard the loud cackle of woodpeckers, as I meandered through the winding paths. Walking down from a steep hillside, I was greeted by the Shakespeare Garden. This mini garden was arranged with flowers and plants from Shakespeare’s plays. Although it was still winter, daffodils were already blooming, along with white and pink hellebores. Rose bushes stood inside the fence, trimmed and naked without leaves, waiting for the spring light.

So, this is what they called “the Ramble”. Ramble is a verb, as well as a noun. I felt the word attract me like a magnet, but I was not sure why.

I spent some hours in this urban forest. I observed a few locals’ birdwatching activities. They were on a bench with their binoculars. An old man in a hat mimicked the sound of a songbird, to attract its appearance. I could only find these birdwatchers quaint. I am not very interested in birds. Still, this was a mysterious place pregnant with a range of meanings for me. Here are a few:

New Yorkers, or some of them, come here to escape the frenetic intensity of the city.

The Ramble is a labyrinth, somewhere you can get lost. In fact, it feels necessary to get lost, at least for a while. Is that how we temporarily lose ourselves?

The Ramble is similar to the centre of one’s own mind, so intimate, yet unknown.

All of these facets were here at the centre of this great city. The Ramble was a place which seemed to have a different dimension. I couldn’t think of any place like this in the cities I had lived in, such as London and Beijing.

I walked along First Avenue, parallel to the gigantic Stuyvesant Town – Peter Cooper Village, a large residential development. The concrete monster seemed to replicate itself wherever I turned. The architecture repeated, with monotonous brown squares. I was hungry. But I didn’t manage to find any interesting food stores. There was only this superblock, containing multitudes of lives unknown to me. How many floors in each building? Eighteen? Twenty? And how many people live in each tower? How many rubbish bins are offered to the residents in their backyards?

I had been walking for hours, from Midtown all the way down to the Lower East Side. My stomach was empty and I felt thirsty. Finally, I saw a bagel shop. A typical Jewish bagel shop. But behind the counter was an Asian man (Chinese or Vietnamese?). An Asian woman was counting coins. Both moved slowly and wordlessly, their eyelids half closed as if they were still asleep. They did not talk, so I could not detect their language, or accent. I rarely eat bagels. Nevertheless, I bought two with cream cheese.

Now I really wanted to get out from this concrete fortress. With my sore feet and tired legs, I wondered if I should go to Alphabet City. From there, I could find the footpath to the Williamsburg Bridge and, eventually, arrive on the other side of the city.

I was back in West Harlem. I left the Hudson river, and crossed Riverside Drive. I arrived in a large supermarket. I looked at the products I was not familiar with. I bought a can of garbanzo beans. Or should I say chickpeas? The name ‘garbanzo beans’ sounds exotic to a Chinese person. I remembered some lines from an Allen Ginsberg poem:

America when I was seven momma took me to Communist Cell meetings they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket a ticket costs a nickel and the speeches were free everybody was angelic and sentimental about the workers

I never understood the bit about “they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket”. So, Americans would fry and then dry that sort of bean so they could sell them as snacks? In any case, it felt like a good deal for a kid attending Communist meetings. My father was a member of the local Communist Party in Wenling, Zhejiang province, and when I was young he would often take me to his evening meetings. I would sit on a bench at the back of the crowded and smoky hall, with a handful of roasted soybeans in my pocket and a stack of homework on my knees. The meetings lasted for hours, sometimes till past bedtime.

A few hours later, in my rented apartment next to the Hudson River, I opened the can and poured the beans into a boiling soup. I cleared the remaining ones from the can, and ate them. I liked the texture. Mushy but still intact, with a trustworthy earthy taste.

I thought of the Chinese name, 鹰嘴豆 – the bean with an eagle’s beak.

If America is associated with garbanzo beans for a foreigner like me, then China is associated with soybeans. I think of the legumes I ate every day in my childhood. Yellow soybeans. Green edamame. Blonde broad beans. We called all these round seeds 黄豆 – yellow beans.

My maternal grandmother’s house was next to a soybean processing plant. The premises were constructed from bamboo sticks on a wooden frame, like a large hut without doors. We would enter and stand by the ever-turning mill, and watch the workmen pouring kilos of yellow beans into the grinder. We would also enter the cooking place where they processed the blended bean curd into tofu.

It was not really a kitchen, there were no woks or pots, just a large brick platform built on the ground with a fire underneath. When the fire was not burning, the tofu makers, mainly men, who were barefoot, would step onto the cooking platform and stamp on the bean curd to flatten the solid mass. I always worried about whether the men had washed their feet before trampling all over the pale yellow blobs. But their feet were as white and as pale as the beans, even though their arms and faces were deeply tanned. And they were always covered in sweat. Their sweat rolled down from their cheeks, like syrupy beans, dripping onto the steamed mash.

‘Such hard work, as hard as growing rice in the paddies!’ My parents would say this to me while buying a kilo of freshly made tofu, still steaming and hot.

Sometimes, my brother and I would also go to the processing plant to buy freshly-brewed soy sauce, collecting it in two large tin cans. We would then walk out, passing donkeys arriving loaded with supplies of fresh beans in baskets. We would go home sauntering along the river which passed by my grandmother’s house. I remember the large pebble stones on the riverbed and how clear the water was. I could see shrimp and eels swimming in the stream. In the near distance, I could see fields of rapeseed flowers and tea plantations on the hills, which had been tended by the locals for centuries.

When I was 19, I went to study in Beijing and was separated from that familiar southern landscape – the semi-tropical climate, the vegetation, the mountainous surroundings, the agricultural life. Not only from that landscape, but also from direct contact with the earth itself – crops growing in the spring and maturing in the autumn, then being metamorphosed through food processing. My separation from that kind of life has been absolute. I have not returned to that part of the world for many years.

If America is associated with garbanzo beans for a foreigner like me, then China is associated with soybeans

I was reading in my room while dusk descended on the Hudson. I could not concentrate, because I was frustrated that I was too late that afternoon to register for health care in a downtown office. It was Friday. I still did not have my Social Security number. Without it I could not get paid or open a bank account in the United States.

I ruminated on the concept of dwelling – 栖. Can I relocate myself again, having already moved to a new continent once? ‘To dwell’ is different from ‘to live’. To dwell is to settle in a particular place. The Chinese character 栖 comes with the ‘tree’ radical, 木. To settle down is to live beside trees, among woods. If there are no trees, there is no home. One of the earliest quotes about the concept of living is from the philosopher Zhuangzi, 2,400 years ago: 居处也, 处心至一之道. Home is where the heart can settle, the way towards Tao – the natural flow of all things.

Dwell. This is a Germanic word. Perhaps the most famous usage of this word is in German poet Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem ‘In Lieblicher Bläue’ (In Lovely Blue):

Is God unknown? Does he manifest as the sky?

This I tend to believe. It is the measure of the man.

Well deserving, yet poetically we dwell on this earth.

We are supposed to dwell on this earth poetically. The philosopher Martin Heidegger used this concept in one of his most well-known essays, ‘Poetically, Man Dwells’. He believed we dwell altogether unpoetically in this world, but the inner poetry is always there. I’m not sure, but I want to agree. Life is a vast spiderweb of trivial tasks. Renting a flat and dealing with energy bills and the cost of living; finding an accountant and seeing a dentist without fearing the bills; eating, cleaning, excreting. We live in a confined urban space with a few pot plants on the windowsills under light bulbs. Yet there is poetry to be uncovered, or at least I like to think so. Sometimes I feel dwelling and poetry belong to each other, because there is inner poetry in our yearning for this connection. Other times I wonder if life has no meaning at all. We try to make meaning because we cannot bear there being none.

The light was fading, I wanted to get ready for bed. When one is alone, one sleeps either very early or very late. Maybe the strange New York sirens would wake me. The sirens in America have different sounds to those in Europe. They wail with short but constant splatterings, like a demented whale weeping.

There was a constant drone of sirens along the riverbank of the Hudson that night. They did wake me up. Perhaps I went to sleep too early. I got up. I switched on the light. It was only ten in the evening. It was too early to go back to sleep. I got dressed, took my keys and went out.

Like a sleepwalker, I wandered without direction. I was aware that there were no stars at all in this part of New York. Even the Hudson River was completely illuminated by both sides of the cityscape. New Jersey was out there, with millions of lit buildings, as awake as Manhattan. I walked down the slope of the riverbank. Suddenly I noticed my shoes were wet, and one foot was on a rock submerged in the water. I could see almost everything on the fluid surface. I could see algae, some little drifters, a Coke can stuck in between floating branches. I bent down, and half sat on a branch which spread out behind me. I saw something moving in the wet sand. A little creature. I brought my face closer. I could not see what it was. An airplane passed above me. Then another. I looked up. Were they coming or going? I looked down into the sand again. This time, I saw a little crab, digging in and out beside my feet. A crab – grey, modest and discreet.

I watched the movement of the little crab for a long time, until it disappeared. I saw myself as this crawling thing. I did. I imagined myself moulting, trying to come out from my old skin, hiding away until the new shell hardened. It must be a hard business.

I waited for a while, by the Hudson river, to see if I would find the crab again, or some other little creatures. But I only saw the quiet shimmering water under the illuminated Manhattan sky. The night was growing more peaceful. It must have been past midnight by now. I decided to return to my apartment.

I went back to bed and read about crabs’ moulting. When a crab moults, the old shell softens and erodes away, while a new shell forms. At the time of shedding, the creature takes in a lot of water so that it will expand and can crack open the old shell. The creature must then extract all of itself, including its legs, the lining of the digestive tract, its mouthparts and eyestalks. This is a difficult process that takes many hours, and if a crab gets stuck, it will die. I could not help trying to imagine the two eyestalks being prised out of their encasements! If the crab fails to bring out its eyes, would the creature survive as an eyeless animal? After this process, the crab is finally free from its own bony prison but it is extremely soft, and it must hide until its new shell has hardened.

So the little thing I saw in the shallows of the Hudson could have been hiding away after moulting. Or perhaps it was looking for a rock under which to shed its shell, but my appearance had disturbed it. Or might it have been on its way to mate? Apparently, mating happens just after a female crab has shed her old skin.

The home of a crab is its own shell. It lives in that home for a while then abandons it, and creates a new one. That’s not unlike us humans. Our house is the exterior of our bodies, and we can move out or abandon it, then make a new house. But some people get stuck in their particular lives and are unable to come out. Just like some crabs, they die in their old skins, unable to fully moult.

The heating was too high. I opened my windows, and stood there for a while watching the sky and the river below. While the chilly wind blew my hair, a tumble of thoughts flew about like troublesome insects. I thought of the fact that I was in the U.S. by myself, having left my child and her father in England. What was I doing, pacing around at midnight in this foreign city? Perhaps I was searching for adventures and encounters and, ultimately, some sort of freedom that I had never had in China or Britain. But what was this freedom? Illusion, delusion or unrealised possibility? Or was it the freedom beyond a woman’s house, with or without a “room of her own”? My thoughts were insubstantial and weightless. Was there real freedom in this city?

The sirens in America wail with short but constant splatterings, like a demented whale weeping

I thought of women’s freedom. I thought of children, family, possessions. I thought of the physicality of female bodies and the judgements of society. To find freedom, you have to be able to describe yourself and where you are in your life. I knew that a vocabulary fit to describe the limits of women’s freedom had already been forged by generations of feminists, and by contemporary social media. But it was a generalised vocabulary for all women, whether white or black, whether working or unemployed, whether married or single. In this, I could not find a lexicon for myself.

Each woman needs to find her own words, that private, special vocabulary she can use to express her condition. To make these words her own she needs to embark upon an etymological journey deep within herself. The words that will be in her possession can be shared, but not turned into slogans. They cannot be taken away from the particular. In that sense I am neither woman nor Asian, neither worker nor oppressed citizen. I am just a human who cannot overcome, or deny, a very specific past, set in stone, real, unfathomably rich in detail, loaded with a finely wrought mesh of social baggage.

I had been enveloped in a sense of my own troubled reality since I arrived in America. I felt threatened by the real possibility of a deep and irrevocable separation from my past, and by being in between worlds. I was experiencing a dreadful sense of incompleteness. A thick melancholy, like the night fog upon the Hudson, lay on me. If a crab had its own private language, fit to describe its own sentient history, then what is my lexicon, which describes this being that I am?

I, this person looking out at the dark river now, had these feelings that couldn’t be caught in a net of ready-made words, nor paved over by any familiar lexicon. If we are honest, we must acknowledge our deep need to communicate, beyond the rigid vocabulary of feminism and politics, and to reach for a language that is authentic yet remains uncategorised. We are trying to articulate something, but it’s intangible. I looked outside, trying to find the moon or the stars, but none were visible in the drenching light of New York City. ∎

Excerpted from Radical © 2023 by Xiaolu Guo. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

All images by Xiaolu Guo, courtesy of Grove Press.

Xiaolu Guo is a Chinese-British novelist, memoirist and filmmaker. Her novels include A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers (2007) and I Am China (2014). Her memoir Once Upon A Time In The East (2017) won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize. She is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and was a jury member for the Man Booker Prize 2019.