Sign up for our newsletter to be notified of new posts!

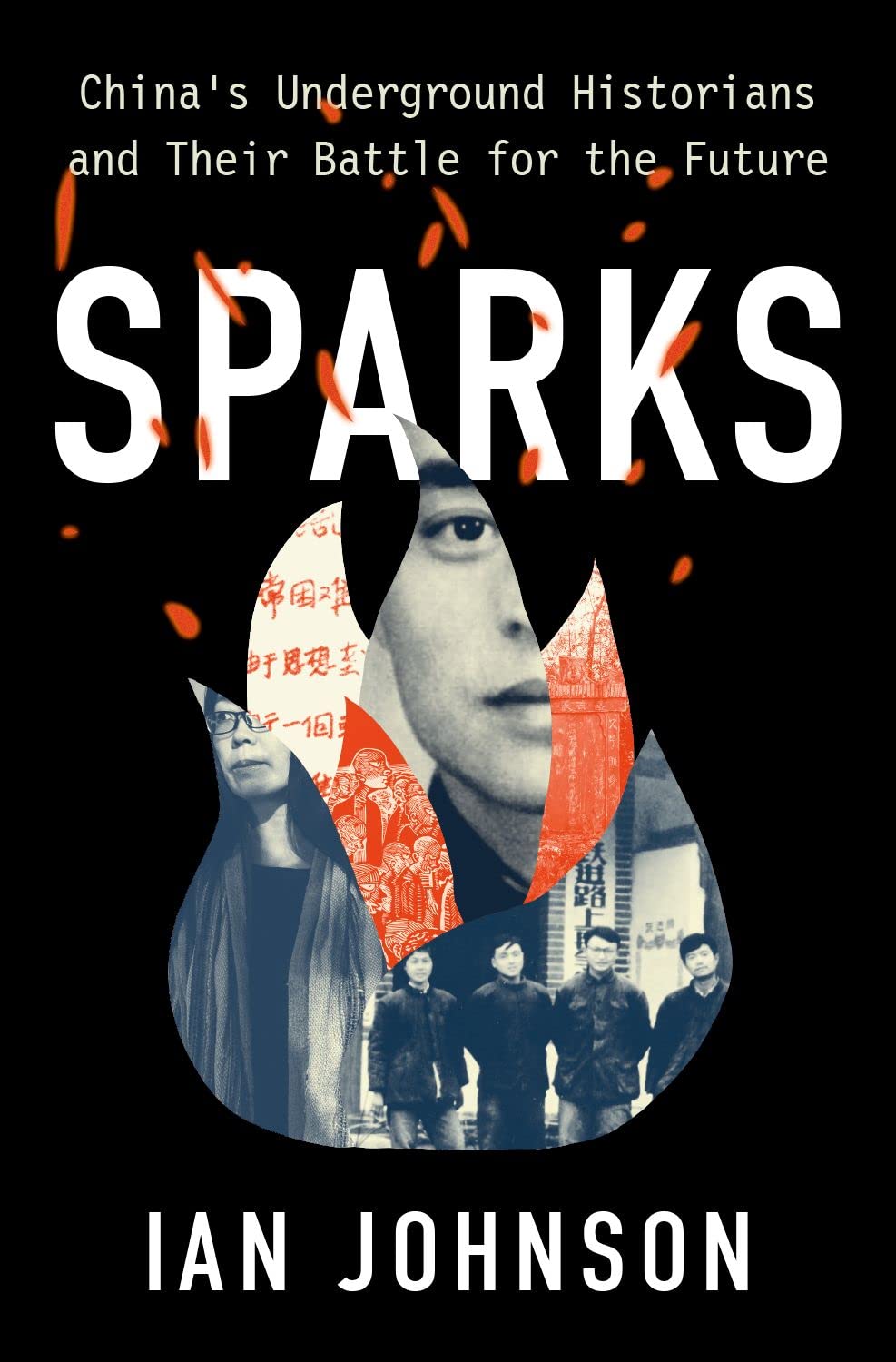

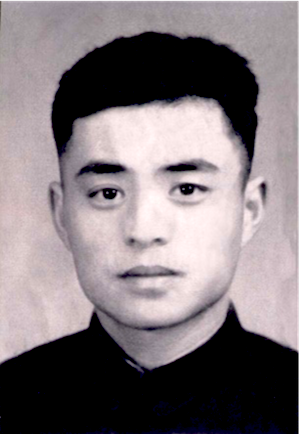

Zhang Chunyuan had all the makings of a loyal communist. A native of rural Henan, Zhang and his family had only known hard times. The area was always on the verge of famine, and that made many people interested in the Chinese Communist Party’s appeal to social justice and economic development. In Zhang’s case, the Party was also an ersatz family. His mother had died when he was seven and, in his telling, his stepmother had treated him cruelly.

At 13, he ran away from home, never to return. He worked as an apprentice car mechanic and then joined the People’s Liberation Army in 1948 as a 16-year-old. When China entered the Korean War in 1950, he volunteered and was wounded when his convoy was strafed by US fighter planes. His neck was permanently damaged and in 1954 he was discharged. He took advantage of policies favoring veterans and entered Lanzhou University’s history department.

That began his disillusionment with how the Communists were running China. He thought a university would have a magnificent library but found that most books were under lock and key. Lanzhou University didn’t even possess a complete set of the Confucian classics — the basic texts used over the centuries by all literate people — let alone cutting-edge journals. Teaching was worse, with one lecturer for 100 students.

When the Hundred Flowers Campaign began in 1956, in which the Party encouraged citizens to voice their opinions, Zhang criticized the lack of books and poor teaching. For that, he was accused of trying to overthrow the university and in May 1958, as part of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, he was exiled with a group of forty other students and faculty to Tianshui, a city in the southeast of Gansu province at the boundary of the Loess Plateau and the Qinling Mountains.

In Tianshui, traditional society was being torn apart. Mao’s violent revolution had left temples dedicated to folk deities empty and desecrated. Farms were still divided into small plots for farmers to grow their traditional crop of wheat and sorghum, but every square inch of land in the People’s Republic actually belonged to the state. And for the sharp-eyed, new buildings hinted at the state’s unbridled power. One housed the local Communist Party offices, where Beijing’s orders were disseminated to villagers. Another was a new garage, which held a tractor — the first promise of the Party’s pledge to modernize rural life. The village had just one of the machines, and the farmers shared it. In the past, life centered around communal religious life; now it was to revolve around a new god, science, and its guardian: the Communist Party.

Zhang took up his job at the tractor station with gusto, fixing and driving the valuable piece of equipment. At night he even wrote a film script, “Children of China and North Korea,” which talked about the ties binding the two socialist countries. He used a pseudonym to send it to a movie studio that was sponsoring a competition, and won a prize worth 700 yuan, a small fortune back in the 1950s. The script was set to be produced until the studio delved deeper into the mysterious author and realized that it had been written by a convicted Rightist.

Zhang, though, was irrepressible. As a boy he was given the nickname “Screw” for being unbreakable when his mind was set on something. That made him cut out to lead the other students, because he had the toughness to do more than just talk — he could get things done. But his uncompromising attitude also led him to take huge risks.

In Tianshui, he once heard that a classmate was being detained by railway police several hundred miles south for having illegally ridden the rails to escape the Great Famine of 1959. Zhang forged an identity card as a Public Security officer and traveled down to straighten out the situation. He bluffed his way past railway guards and local police to get the young man released, returning in triumph, convinced that he could achieve anything.

The group of exiled students often met at Zhang’s tractor station. It was conveniently located on the main road, and Zhang was an amiable and thoughtful host. Broad and strong, with thick eyebrows and a square face, he had sensitive eyes and loved to read. His knowledge complemented his war experiences, which made him more mature than the bookish students. But he didn’t lecture or talk down to them, instead engaging them in long conversations about their country’s future. One point he returned to time and again was how they, even though just exiled students, were duty-bound to help their country.

“He really opposed those who only thought of themselves,” Tan Chanxue, one of the students, recalled in her memoirs. “He never thought that his own liberty counted for much.”

Famine was taking hold, and the students saw the gruesome effects firsthand. They were able to withstand the lack of food, but they saw the elderly, the weak, and the very young slowly die

In more densely populated areas farther east, the students probably would never have been able to meet at a place like Zhang’s tractor shed. Tianshui, however, was remote and poor, and local officials were eager to promote literacy. So they set up an open university, appointing the students as faculty. That gave the young people an excuse to meet and travel around the region. These face-to-face meetings, they realized, were crucial. Working alone resulted in nothing. A pebble can’t break a rock, Tan said, but perhaps many pebbles tied tightly together could smash it.

Everyone in the group became good friends, but Tan and Zhang were particularly close, later declaring themselves to be husband and wife. A slender 24-year-old with thin, arching eyebrows, Tan came from southern China’s Guangdong province near the Hong Kong border. While Zhang was bullheaded and brusque, she was gentle, with calm eyes and a reasonable demeanor. There were many obstacles to a love in a famine-ridden land run by a totalitarian dictatorship, but their feelings blossomed. Soon, they would risk their lives to prove their love.

By May 1959, the group was debating issues such as how to rid China of the Communist Party, or at least the current leadership that had caused the famine. Zhang said there were two options: a top-down coup or a bottom-up revolution. The latter seemed impossible and so they hoped that Mao’s peers would act. And in fact, something along these lines is what some people in Beijing were planning. Over the summer, one of China’s most-decorated military leaders, Peng Dehuai, challenged Mao for causing the famine, but Mao held a pivotal meeting in the mountain-top retreat of Lushan. Peng was crushed and Mao redoubled his economic policies, causing the famine to deepen, eventually taking up to 45 million lives.

When Peng’s downfall was made public, the students felt certain that they had to act: if even a general at the top could be persecuted for expressing loyal dissent, then the only hope was to foment something at the grass roots. They thought that their best bet was to publish material on the famine in hopes of sharing ideas and opening up officials’ eyes to what was going on in the countryside. They began to think of publishing a journal.

The idea remained vague until they came across a remarkable poem. It was written by a student at Peking University, Lin Zhao, who had been studying in Beijing until she was labeled a Rightist for defending friends who were being persecuted. Lin’s poems galvanized the students, showing them the power of the written word.

Like Zhang, Lin was more experienced than many of the younger students. Born in 1932, she had worked as a propagandist for the Communists shortly after their takeover in 1949. At the time, she went along with their violent policies and participated in the land reform campaigns that saw hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of property owners murdered — a genocide aimed at eliminating the elite that had run China before the revolution. But with time she began to see that the Communists were not building a utopia but a tightly controlled authoritarian state. As a young girl in pre-Communist China, she had attended a Methodist girl’s school. Now she returned to her faith and experimented with art to express her independence from the party. When her friends were arrested, she wrote a poem declaring:

The power of truth

never lies in

the arrogant air

of the guardians of truth.

Lin later wrote a 240-line poem called “Seagull” and circulated it among friends. One friend was the sister of a member of the group of Tianshui students. The woman mailed a handwritten copy of the poem to the exiled students, who were thrilled by Lin’s bold imagery and overtly political message. The poem tells the story of a ship carrying chained prisoners. Their crime: they seek freedom.

Freedom, I cry out inside me, freedom!

The thought of you has filled my heart with yearning,

like a choking man gasping for air,

like one dying of thirst lurching toward a spring.

Zhang decided that he had to meet the author. After being arrested in Beijing, Lin was released after her chronic tuberculosis worsened, and she began spitting up blood. She moved back to her hometown of Suzhou on China’s east coast. She was immediately put under close surveillance. But Zhang once again took another huge risk, using his forged identity papers to travel days by train and then arranging to meet her. Lin urged Zhang not to print her poem, seeing it a risk to the group and to anyone who read it.

But then Zhang read Lin’s second poem, a 368-line work called “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion.” It used Christ-like motifs that reflected Lin’s renewed Christian faith. The poem tells of an encounter between Zeus and Prometheus, who is chained to a rock for giving humans fire. Zeus explains that his punishment is necessary because humans must never have such an important tool:

But you ought to know, Prometheus,

for the mortals, we do not want to leave even a spark.

Fire is for the gods, for incense and sacrifice,

how can the plebeians have it for heating or lighting in the dark?

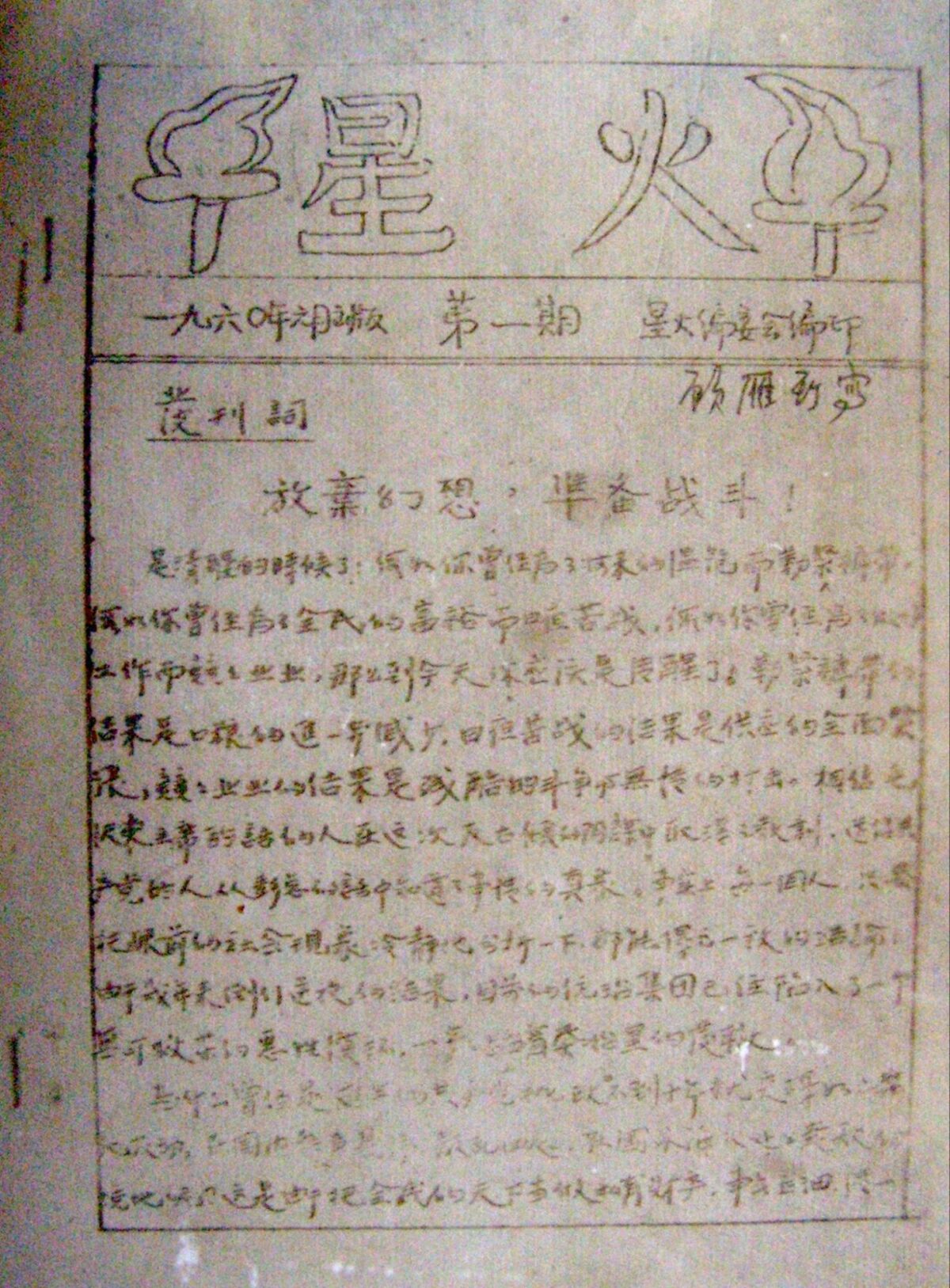

Zhang convinced Lin to let them publish the poem and decided to put it in the first issue of their new journal. Students from Beijing also passed him materials about how Yugoslavian Communists were trying a hybrid form of socialism that allowed for capitalist-style incentives (something the Communist Party would embrace twenty years later). Zhang decided to add that material, too, to the inaugural issue, as well as essays by himself and others in the group. The journal needed a name. They quickly settled on Spark (星火), based on the idiomatic expression xinghuo liaoyuan, or “a single spark can start a prairie fire.” Mao had also used it in one of his essays, making it widely known.

A pebble can’t break a rock, Zhang’s partner Tan Chanxue said, but perhaps many pebbles tied tightly together could smash it

Two members of the group, physics student Miao Qingjiu and chemistry student Xiang Chengjian, were entrusted with printing the first issue. They had been assigned to work at a sulfuric acid plant in the nearby town of Wushan. The plant had an old mimeograph machine, which they could occasionally access. Their jobs also required them to cultivate bacteria used to make fertilizer, a process that required a sealed-off space. This allowed them to bar themselves in the room with the mimeograph machine, claiming that they were making the bacteria.

The two spent eight nights in January 1960 carving the plates by hand — there was no typesetting or other equipment available. The process, though, was too slow. Miao and Xiang would eventually have to open their office, which would endanger the enterprise. As always, Zhang came up with the solution. Inside his tractor shed was an old motor. He gave it to Miao and Xiang, who sold it to their factory cheaply. They used the proceeds to buy a used mimeograph machine. The group kept that at the home of Gu Yan, a graduate student in physics, who lived near Zhang. He also carved essays on that machine’s drums, and drew the magazine’s logo, a torch with a flame leaping upward. They ran off thirty copies. Spark was born.

At just eight pages, handwritten, and with no photos or graphics, Spark was primitive. But it was filled with articles that got to the heart of China’s conundrum — then and now. The lead article on the first page by Gu Yan set the tone. Called “Give Up Your Fantasies and Prepare to Fight!” it asked questions that Chinese people have posed time and again over the decades:

Why did the once progressive Communist Party become so corrupt and reactionary less than ten years after coming to power, with complaints and rebellions at home, and falling into an embarrassing situation abroad? This is because the people’s world is regarded as its private property, and all matters are managed by party members.

One key problem was due to “idol worship” — alluding to the personality cult surrounding Mao Zedong. But it also pointed to broader problems, such as the state’s unlimited powers: “political oligarchs being arrogant, and perverted. If such a dictatorship insists on calling it socialism, it should be a kind of National Socialism monopolized by a political oligopoly. It is of the same type as Nazi National Socialism and has nothing in common with real socialism.”

Writing about the famine, Zhang Chunyuan penned an essay simply titled “Food Matters.” He blamed the Chinese Communist Party for exploiting the farmers: “Today’s ruler, like any ruler in history, used the peasant revolution to climb Tiananmen Square and ascended to the throne.” After that, China’s new rulers trampled on the farmers, leaving them no better than serfs. In another essay, he pointed to the lack of land ownership as a key problem facing farmers.

A few months later, the students met again and decided to make Spark a regular publication. The goal was to mail it to high-level officials in five major cities — Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Xi’an — where the students had contacts. They began writing more essays, including Zhang Chunyuan’s “On People’s Communes,” which dissected how farmers lost their property, and Xiang Chengjian’s “Letter to the People,” a takedown of top leaders:

When millions, tens of millions of farmers starve to death on their beds, on trains, by railroads, at the bottom of a ditch, when hundreds of millions (400 million) people are dying of starvation, when the other 200 million are half-starved. When they are full, those animals who “wholeheartedly” serve the people and are “people’s servants” can buy any snacks, biscuits, candies. … They feasted and walked away (who would dare to ask them for food stamps), and as soon as they arrived, the meal was served.

Xiang continued in this vein by pointing out the moral relativism of China’s top leaders. Decades before Mao’s private doctor shocked the world with his tales of Mao’s sex with young women, Xiang pointed out the hypocrisy of the older men who led China. While appealing to steadfastness and loyalty, they had taken up with younger women, casting aside their wives who had suffered with them while they were fighting for the revolution. Even worse, information had come to light during the Anti-Rightist Campaign showing that many officials freely took the daughters and wives of persecuted families.

Lin Zhao’s poem “Seagull” was also slotted into this issue. It was engraved onto cylinders in addition to Zhang’s “On People’s Communes.” While they were figuring out the logistics of engraving and then distributing their new issue, they ran off 300 copies of Zhang’s article because of its importance in analyzing the root causes of the famine. The idea was to mail out that article first and follow it up with the full issue.

As the second issue neared publication, the group began to debate what to do next. They decided they needed some sort of organization and ways to spread their appeal beyond the narrow group of exiled students. They also felt that someone had to escape from China and find help, or at least get more information about the situation in other socialist countries, such as Yugoslavia. Maybe this would help their country find a way forward.

The journal’s name was based on the idiomatic expression “a single spark can start a prairie fire,” used by Mao in one of his essays

Tan Chanxue decided to try to seek help in Hong Kong. She was from Guangzhou, the metropolis not far from the British colony, and she figured she could make her way across the border. The students were some twelve hundred miles away, but China was in such chaos that it wouldn’t appear odd if a university student traveled back to her hometown to find food. So she made her way south by train and stayed with an aunt.

The two women decided to flee together to Hong Kong and hired a human smuggler to spirit them across the border. They dressed as peasant women and walked to a village near the border. The smuggler, however, was inexperienced and led the women straight into the hands of the local militia, who detained them in Shenzhen — back then still a village, and not today’s city of nearly 20 million.

They tried to play the role of peasants, hoping to be let off with a warning for having strayed too close to the border. So when they were allowed out to do manual labor by collecting firewood, the two did so barefoot, although their soft feet were quickly cut by the rough terrain.

Still, no one seemed aware of her true identity until Tan made a fatal mistake. One day, a guard told Tan that if she wanted to post a letter, he would carry it out and post it. She was supposed to be illiterate but decided to use the chance to warn the group around Spark that she had been detained. A few weeks later, she realized her error. She was taken in for interrogation and asked if she knew a man named Gao Chengqing. This was Zhang Chunyuan’s pen name. How did they know about him?

The letter itself wasn’t a trap. It had been delivered, and Zhang had quickly heard that his sweetheart had been detained. He decided to rescue her, just as he had helped out his friend a year earlier. He used the same forged identity card, which gave his identity as his pen name, Gao Chengqing, and traveled south. But the women were being held in a reform-through-labor facility, which was much stricter than the railway police he had fooled before. The prison’s officials immediately saw through his ruse and put him under arrest. Because they didn’t know his real identity, they booked him by his pen name.

Feigning illness, Zhang met a female doctor who was also a prisoner. Feeling he could trust her, he told her that he and Tan were husband and wife and asked her to pass Tan notes. He wrote several, many of them professing his love and hope for a life after imprisonment. He used an intimate form of address, using only the last character of her given name, xue, which means “snow.”

Snow! It must be a match made in heaven that we can go to jail together. Our feelings will transcend all time and space. May we go out and in, life and death together! The days to come will be long. Take care!

But the doctor wasn’t willing to risk her future for a man she didn’t know. She could gain by informing on him and, anyway, he himself might be a trick to test her. All of Zhang’s love letters ended up in the authorities’ hands.

The authorities sent a political prisoner to live with Zhang in his cell as a spy. The man befriended Zhang, who again fell for the ploy. Zhang confessed everything, not only their hopes to escape but the existence of Spark. Soon, Zhang and Tan were on a train back to Lanzhou for trial.

By September 1960, the magazine was shut down and the case was cracked. In what became the fourth largest “counter-revolutionary” incident in the country, 43 people were arrested in connection with Spark, including 12 university students, two professors, two graduate students, and 25 farmers.

Revenge was swift. The Party convened a “Ten-Thousand-Person Sentencing Conference” in Lanzhou to hand down the sentences to those who were still in Tianshui. Zhang Chunyuan got life in prison. The students who carved the drums, Miao Qingjiu and Xiang Chengjian, got 20 and 18 years. Others got between 15 and five years.

Tan Chanxue spent 14 years in prison for membership in a “Rightist counterrevolutionary clique.” After that, she was forced to take a factory job in Jiuquan, the city near the Jiabiangou labor camp and the satellite launch facility. It was only after her rehabilitation in 1980 that she could leave the factory. She later joined the Dunhuang Research Academy before retiring to Shanghai in 1998. During a trip back to Tianshui in the 1990s, she met people who still knew her case. Once, a woman grasped her hands and said, “You have suffered so!” Tan could only burst into tears.

She was lucky compared to many of the others. The security apparatus quickly picked up those who had fled Gansu. In Shanghai, the physics student Gu Yan, who had come up with the magazine’s name and logo, received a 17-year sentence. The prison term for Lin Zhao, the poet whose work inspired Zhang to launch the journal, was 20.

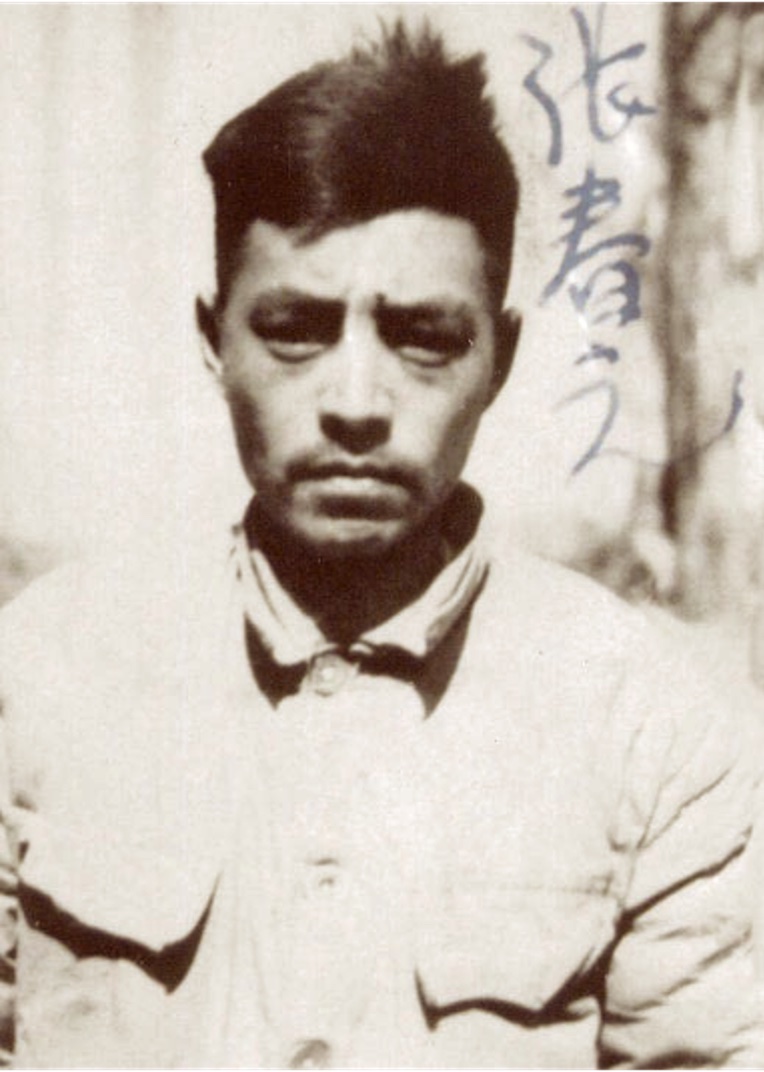

Many fought their fate, especially Zhang. In July 1961, he feigned illness and was admitted to hospital. During the midday siesta, while everyone was overcome by the summer heat, he changed into street clothes and walked out of the hospital. He hitched a ride to a nearby town, then walked 19 kilometers to a logging camp where a friend worked.

He lived in his friend’s logging hut, regained his strength, and then set off to Shanghai to see what had become of his friends. He found that Gu Yan had already been arrested. Then he went to the neighboring city of Suzhou to learn that Lin Zhao had also been arrested. He wrote her a postcard, signing it with her mother’s name but figuring that she would recognize his handwriting: “Our life is so rich in materials that we could write a novel that hasn’t been seen in ancient or modern times, at home or abroad. I hope you can read this book, this book that cost us so dearly.”

Zhang then moved on to the nearby city of Hangzhou, feeling guilty that he was free while his friends were in prison. It’s a measure of the turmoil in China brought on by the famine and political instability that he stayed free for so long. But then the inevitable happened. As the famine was brought under control, the government reasserted itself. Zhang was picked up in a street sweep of homeless people. He was identified and sent back to prison in Lanzhou.

While Zhang was bullheaded and brusque, Tan was gentle, with calm eyes and a reasonable demeanor. They risked their lives to prove their feelings

A few years later, the Communist Party’s next convulsion, the Cultural Revolution, proved deadly for some of those in jail. After a brief period of chaos at the start of the Cultural Revolution, the Party promulgated new rules to “strengthen public security work.” That resulted in harsh crackdowns across the country. Young people were once again sent to remote areas to work. Prisons carried out mass executions of convicts.

In 1970, local authorities in Tianshui decided that the new rules meant that Zhang should be executed on the grounds of being in an “active” counterrevolutionary cell — a capital offense. For a few months before his execution, Zhang and Tan were housed in the same prison. Tan wanted Zhang to know, before his death, that she still loved him. She asked someone who delivered him his meals to tell him that “he will always live in my heart.”

Zhang was sent to the Lanzhou Detention Center to be executed. The prison was nicknamed the “kiln,” a castle-like complex with walls 10 meters high and topped with barbed wire. When he entered his final cell, number 12, he was wearing a black cotton prison shirt and trousers, a black cotton cap, and black cotton shoes without laces. Heavy shackles weighing about fifteen kilograms were attached to his ankles, which were wrapped in cotton to prevent bleeding. His hands were cuffed tight behind his back. He could only clutch his sole belongings, a chipped enamel bowl and cup stuffed with a rolled-up white cotton towel. He could drop his trousers to urinate or defecate but inmates had to help him pull them back up.

The dozen or so prisoners in the room roused themselves to look at the condemned man. He apologized for bothering them and waited politely for someone to make space for him to sit down. The men were dumbfounded and soon made space.

The prisoner in charge of the room was a man named Wang Zhongyi. He had been rounded up in a sweep of young people and charged with hooliganism. Now he was under orders to make sure that Zhang didn’t commit suicide. Over the next three days the men became close and Zhang entrusted Wang with telling Tan how much he loved her.

One of the young men asked Zhang if he was scared. His case was serious, wasn’t it? Zhang replied: “Yes, it’s serious: active counterrevolutionary activity.”

Zhang told the men his life story. Then, on March 22 he was led out to the Qilihe Stadium for a mass sentencing. Before he left, he made Wang promise that somehow, someday, he would find Tan and tell her two sentences: “First, I have a clear conscience toward the Party, the country, and the people, and I’m sorry because I can’t accompany her to finish the road of life. Second, she must live well; the future is bright and boundless!”

Zhang was condemned to death and then taken to Willow Gulley in Donggang Township, where he was shot. After his death, a notice was put up in various prisons around the district. One was Tan’s women’s prison. Tan saw it. Within a month her hair had gone white. ∎

Postscript

The magazine Spark lasted only a year before it was extinguished. It never circulated nationally. It resulted in no protests or any sort of threat to the government. Over the Chinese Communist Party’s three-quarters of a century in power it is one of countless small acts of outrage against its unchecked powers. And yet, due to case files released in the late 1970s and 1980s, including the love letters between Tan Chanxue and Zhang Chunyuan, the story was preserved. In the 2000s, the underground filmmaker Hu Jie interviewed most of the survivors and in 2013 released online one of his best-known films, Spark. Over the past two decades, this story has become a touchstone in Chinese people’s efforts to counter the Party’s efforts to whitewash the past. Read more about it and similar stories in Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and their Battle for the Past.

Adapted from Sparks © 2023 by Ian Johnson. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher. Copyright © 2023 by Ian Johnson and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

All images courtesy of Oxford University Press.

Ian Johnson is the author of four books about China, including Wild Grass (2004), The Souls of China (2017) and Sparks (2023). A Beijing-based correspondent for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and other publications for 20 years, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on China in 2001. Johnson is currently based in Berlin.