What do we mean when we talk about “Chinese literature”? Grand statements only capture a partial snapshot of a full and complex scene. And not just one scene, but a polyptych of connected images, a prism of dispersed light. Whatever its shape and form, Chinese literature is big, and however we slice it — nationally, ethnically, linguistically — we risk being culturally or politically insensitive. There are, after all, hundreds of languages or dialects spoken in China alone, and many more across the Sinophone world.

For the purposes of this quarterly round-up of recent Chinese literature in translation — a continuation of the “New China Books” column, following Alec Ash’s earlier list of China nonfiction — we cast a broad net. Anything recently translated from Chinese into English, or from a broadly-defined Chinese-language territory, is game (there are books from Malaysia, Hong Kong and mainland China in this installment alone) — mostly fiction, but with other genres creeping in at the edges.

The translation collective Paper Republic (which I’m part of) publishes an annual roll call of Chinese literary titles translated into English, averaging at 45 books a year. (A number we hope goes up.) In the list below, I’ve made it even easier for overburdened readers by recommending just five recent titles, in no particular order, that you may want to know about — or hopefully pick up and read. And what treats we have for you this Halloween (no trick): donkeys that can see ghosts; dystopian visions of Hong Kong; an experimental novel from Malaysia; a cosmic trip to the doctor; and a tour of contemporary Beijing. Happy reading!

Bearing Word

Xinjiang, China’s northwest province that novelist Liu Liangcheng calls home, was once the site of a millenia-old religious conflict between three kingdoms vying for power. Now, thanks to Liu’s animist lens and Jeremy Tiang’s lyrical translation — which at times could be mantra or windsong — this ancient chapter in the history of the region has been given new life. In its vast, stark plains, spirits of the dead bicker over whose dismembered body a pair of legs might fit; religious devotees build grand pagodas with their chants; and only donkeys understand any of it. A “word-bearer” and hyperpolyglot translator named Ku is tasked with escorting a jenny called Hsie across the Gobi Desert, traversing the territories of two kingdoms who have been at war for so long that the cause has been all but forgotten. Unbeknown to Ku, Hsie carries a scriptural message on her skin, hidden by fur. With absurdity and bawdy humor aplenty (see: fart-fueled acts of revenge and humongous donkey phalluses) as well as meditations on loss, language and the brutal reality of war, this novel conjures laughs, horror and heartbreak in equal parts.

Owlish

A complex and pervasive flavor of depravity is to sit by and watch as oppression and violence are enacted. The reasons why a person might do this are manifold, but for Q, the protagonist of Hong Kong writer Dorothy Tse’s first solo novel, desire is the main motive. A frustrated academic in a lukewarm marriage, he fails to notice (or succeeds in not noticing) the efforts of students and protestors to fight against systemic changes being forced upon his (somewhat) fictional home state of Nevers by the totalitarian Vanguard Party. The Party also controls the neighboring country, Ksana, and regained sovereignty over Nevers from the imperialist nation of Valeria decades before. Q’s main concern, however, is in throwing his horny self into a licentious and exploitative affair with Aliss, a wind-up ballerina brought to life and tucked away in a churchly “love nest” lent him by the all-seeing titular character, Owlish. The book is, of course, an on-the-nose allegory for Hong Kong’s recent history, delivered in often dreamy but always engaging prose by translator Natascha Bruce.

The Age of Goodbyes

This debut novel, by award-winning and best-selling Malaysian Mahua writer Li Zi Shu, relates (in YZ Chin’s lively, robust translation) the ascent of protagonist Du Li An from daughter of a street vendor to boss-lady with a gangster husband. So a straightforward but colorful story about female friendship and strife, right? There’s more. Opening not on p.1 but on p.513, to signify the date of deadly race riots in Malaysia in 1969, the story obfuscates the violence and politics of the riots’ aftermath, creating a sense of mystery that grows as you read on. Whenever an answer about a character’s past or identity seems at hand, one of the two other narrators cuts in, themselves mysterious. One — called only “you” — is a teenage boy living in a rundown motel brothel, reading The Age of Goodbyes and searching for his roots after his mother died. Another is a literary critic obsessed with an author who may or not be Li Zi Shu. This compelling and experimental novel throws into question the very act of narration, in order to show just how profoundly official histories can haunt us.

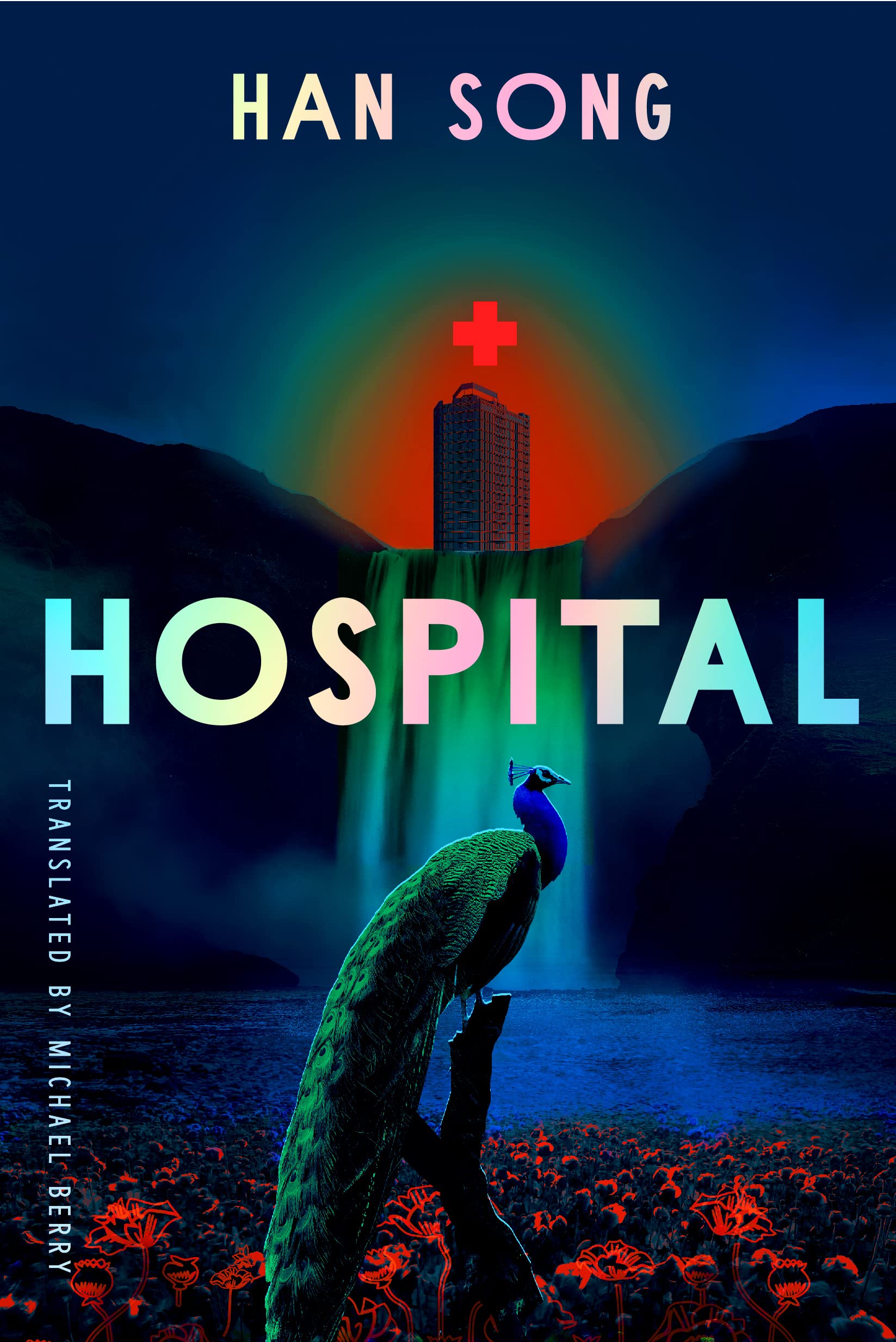

Hospital

A trip to the hospital is rarely a welcome prospect. But what if you didn’t know why you were going there in the first place? When Yang Wei is escorted to the local hospital in “C-City” by hotel staff, after drinking a bottle of water from the mini-fridge, it becomes clear that he’s in for the hospital visit from hell. There are patients who are never discharged, proselytizing doctors that preach the curative power of belief, and giant peacocks bearing red crosses on their bodies. Through it all, our narrator tumbles deeper into a nightmarish and corrupt bureaucracy that feels like a reimagining of Dante’s Divine Comedy for the “Age of Medicine” — a new order in which hospitals have replaced cities, and the notion of “freedom” has been supplanted by “treatment”. Full of lofty dogma, convincingly rendered by translator Michael Berry, the novel satirizes both authoritarian and imperialist propaganda, and blares at maximum volume the Buddhist idea that ignorance is suffering. And this first volume is just the beginning of sci-fi author Han Song’s surreal (or frankly unhinged) Hospital trilogy, with the second title, Exorcism, out in November.

The Book of Beijing

How do you tell the story of a city so large and enduring as Beijing? Three thousand years-old; 22 million people; six ring roads; a torrent of traffic. Maybe it’s best not to try — or not with just one story. Beijing is no monolith, after all. Enter one of the latest releases in Comma Press’s “Reading the City” series, and the second to focus on a Chinese city (after The Book of Shanghai). Ten short stories, all by Beijing-born or -based authors, cover everything from the struggle to stake your name in a dog-eat-dog metropolis, to impossible rent traps where space is at a premium; from relationship difficulties in times of rapid change, to metro trips down memory lane and into a potential near future. With contributors ranging from known entities (Xu Zechen, Gu Shi, Han Song) to relative newcomers (Wen Zhen, Fu Xiuying, Shi Yifeng), the anthology features a motley crew of tales and translators (full disclosure: I’m one of them) that capture contemporary Beijing in all its glory, warts and all. ∎

Jack Hargreaves is a London-based translator from East Yorkshire. His published and forthcoming full-length works include Winter Pasture by Li Juan (2020) and Seeing by Chai Jing (2020), co-translated with Yan Yan; I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan (2025); and A Man Under Water by Xiaoyu Lu (2026). He occasionally contributes to Paper Republic.