At the end of each year, the translation collective Paper Republic publishes a roll call of Chinese literature in English translation. This year, we counted 54 works of translated fiction and nonfiction, as well as poetry, sci-fi, children’s books, a graphic novel and a book of jokes from the imperial era. That number, while higher than last year’s count of 46, continues a downturn from the steady upward arc we saw over recent years (it was 76 in 2021).

Why, exactly, is hard to say. We’re mostly out of the limbo of the Covid pandemic — where book fairs, funding and flights dried up — but the gears of publishing can be slow to get turning. What has stayed consistent is the gender imbalance, with just over half as many works by women as men being published in English (18 to 33, the rest being anthologies). But the quality and range of what was published remains in strong form, especially in nonfiction. And my reading list for 2024 is full of what promise to be queue-jumpers.

Below are five more recently translated books to warm your winter. This list — gathering writers from Singapore, Hong Kong and mainland China in readiness to bring in the Year of the Dragon — is not as overtly political as some titles in the previous installment, but focuses on the personal and private, even if the stories are backdropped by war, tyranny and forced adaptation. Their power comes from tending toward what Eileen Chang called the “placid and static aspects of life” in her collection below. From nonfiction and poetry to short stories and a comic, they are books that bolster the spirit.

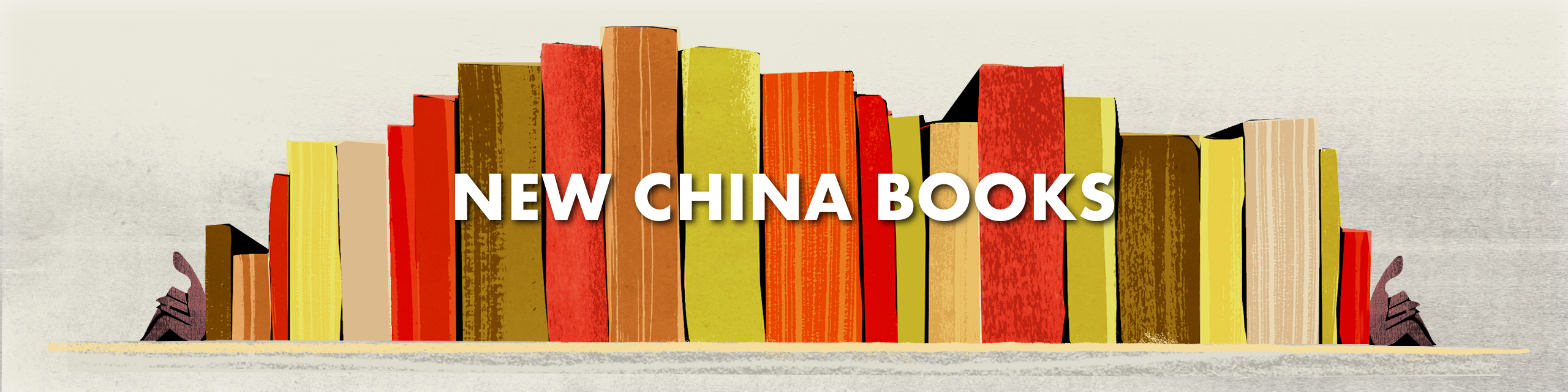

Written on Water

Eileen Chang, the celebrated novelist and essayist who wrote in wartime Shanghai and Hong Kong, thought that her writing “was not meant to endure so much as linger and then fade away,” according to co-editor Nicole Huang’s afterword. Written on Water is therefore an apt title for this revised collection of Chang’s essays in translation, re-released 79 years after she first wrote the book (titled 流言 in Chinese) at the tender age of 24. Yet back then she wished for fame, for fear that it coming later in life might mean “the pleasure of it isn’t as intense” (“Hurry! Hurry!” she added, “Otherwise it will be too late! Too late!”). It’s with this sense of urgency — and cool wit and poise — that she discusses (in Andrew Jones’ brocaded translation) such diverse topics as overheard conversations in the street; the wisdom and enigma of children; the virtues of tight-fitting clothes in turbulent times; umbrellas as class commentary; and men looming large in women’s lives. She wrote what she knew, and with it she made her wish into a reality.

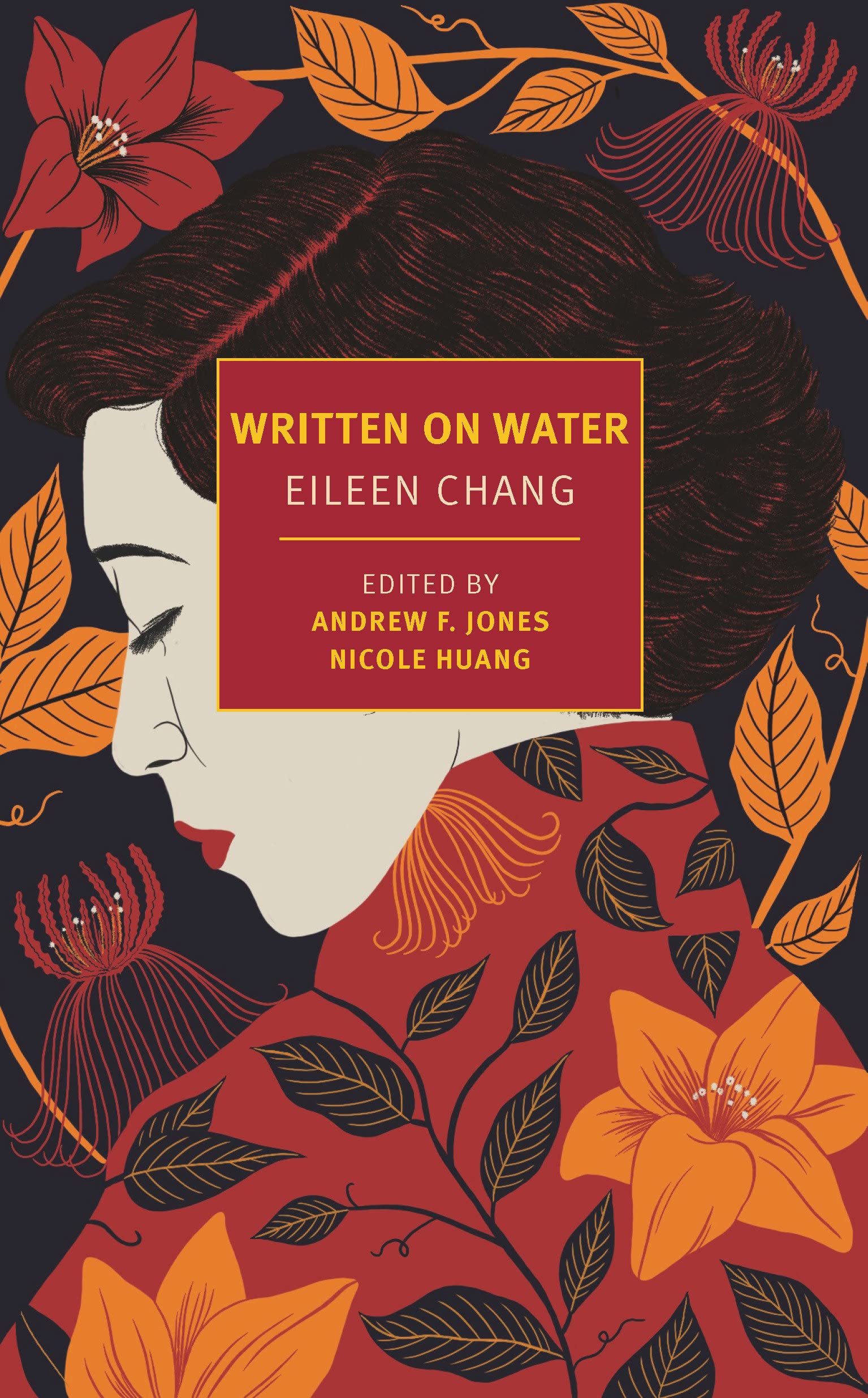

A Cha Chaan Teng That Does Not Exist

A cha chaan teng (茶餐厅) or “tea hall” is a post-war Hong Kong diner that serves comfort food referred to, euphemistically, as “soy sauce Western” — colonial dishes with local twists. Known for inexpensive menus, Cantonese diner lingo and snappy service, this humble cornerstone of Hong Kong culture will be familiar to anyone who has called the city home (or watched a screen drama set there). But the institution might be disappearing. Gentrification and the Covid pandemic have led to the closure of many cha chaan teng across the city, and more might shutter in the coming years. Derek Chung’s poetry collection speaks to this instability, which the poems themselves are working to counter. Zooming in on snapshots of the quotidian, the poems — about housing problems, rapid urban transformation, the SARS and bird flu epidemics — show how a city’s story can live on through its inanimate denizens. This bilingual edition, which puts May Huang’s heartfelt translations next to the complex Chinese originals, is a powerful reminder that sometimes, for tomorrow’s sake, “there may be / Nothing left to do / But to write poetry”.

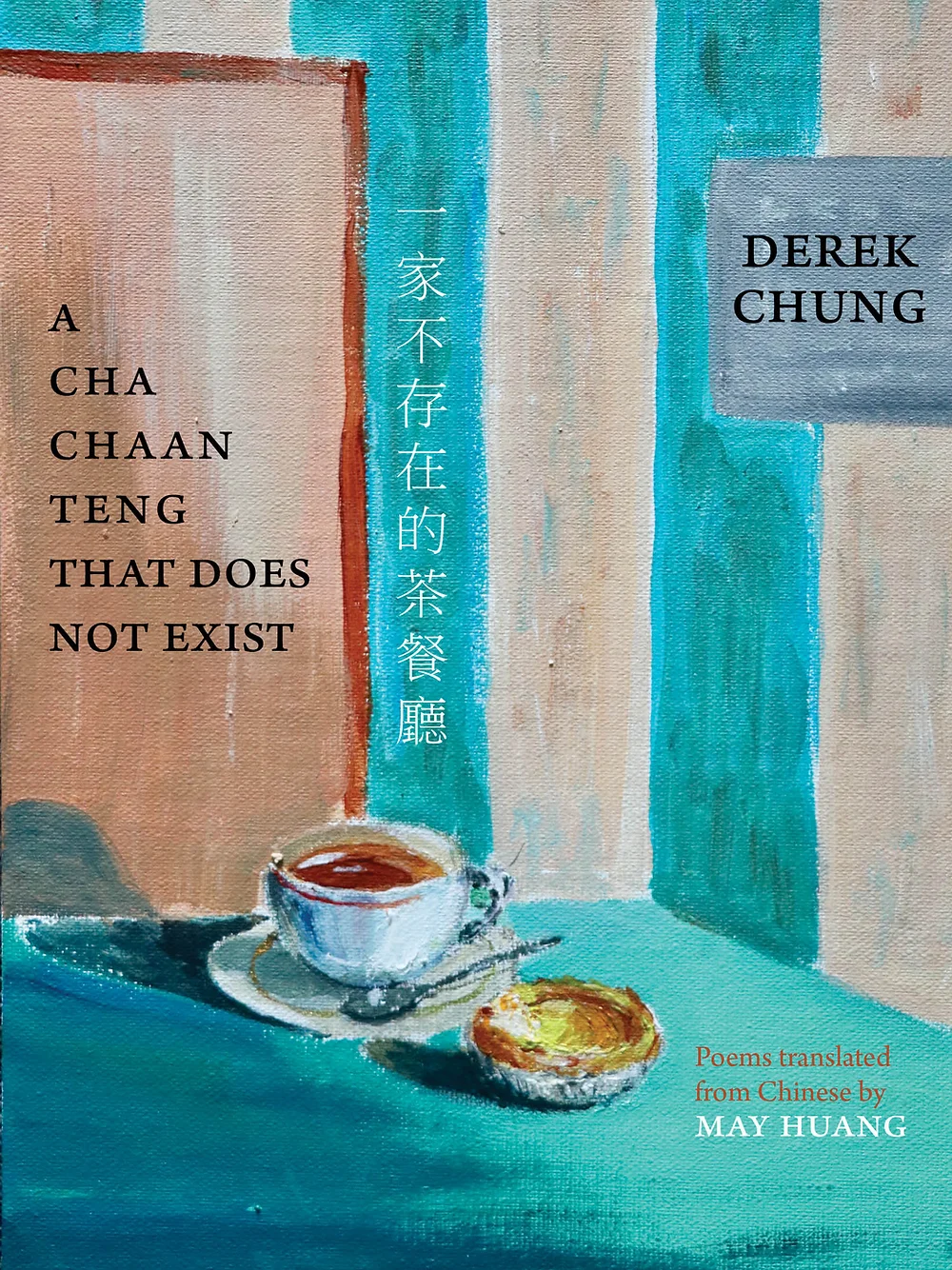

Diasporic

A double recommendation: Diasporic and Clan are two renderings into English of a single short story collection by Singaporean writer Soon Ai Ling. The former is a more traditional, straightforward translation, while the latter is a bolder, more interventionist approach (the translator, Yeo Wei Wei, calls it “transcreation” and “adaptation”). The stories in Diasporic — which span China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the UK and Singapore — look at how intricately interwoven life and art are. Following a family of craftspeople (skilled in cooking, embroidery, batik, opera, jade work and horticulture) each tale shows how the family dynamics find expression in their art. In Clan, Yeo Wei Wei takes their stories a step further. Where the inner lives of the female characters are overshadowed by societal expectations and tradition, here the translator intervenes, rewriting the endings. Now, for example, when the virtuoso apprentice is married off to a “suitable” partner, her teacher is left full of romantic longing. The result astounds: energized by Yeo Wei Wei’s will, the women, and the book as a whole, vibrate with a new possibility and passion.

Beijing Sprawl

Young person leaves home for the bright lights of the big city. It’s an oft-told tale. In author Xu Zechen’s telling, there are few urban destinations more unforgiving than Beijing. A city that sucks in migrants and drifters, chews them up and spits them out again, China’s capital is where high-school dropout Muyu and his friends go searching for “greener” pastures in this collection of interrelated stories. Instead, the ragtag cast of characters find themselves in a sort of recurring nightmare (one of their number even dreams he’s a chained monkey in a suit forced to perform tricks). Day in, day out, they go from selling fake IDs to eating donkey burgers, from fatal brawls to drinking beers on a rooftop. From their latest scheme to their most recent flop, they do all they can to make something of themselves in business and in love. But being a jingpiao — a “floating” migrant in Beijing — means limited access to rights and services, cramped conditions, and an all-around hard lot. The author himself moved to the capital in 2002 and befriended many in this position, so he would know. Still, united by their struggles and a love of banter, Muyu and his friends (rendered in Eric Abrahamsen and Jeremy Tiang’s fizzy translation) ensure that this is a highly enjoyable quasi-sequel to 2014’s Running through Beijing.

Sealf-Care for Everyone

Lessons in life, rest and self-love from the Internet s favourite seal

Feeling down? Insecure? Daunted by work and life? Tired of the hustle? Maybe it’s time you met your inner seal — an adorable animal companion to wellbeing, creation of the Shanghai-based cartoonist Wang XX. This, the second of Wang’s comics to come out in English, is more of a coffee table book than her previous release, Think I’ve Still Got It, a semi-autobiographical comic about Seal’s struggles with freelance life and existential dread. (The publisher described Seal as “a quintessential millennial”; you can read an excerpt here). This new offering is a four-step program to “sealf-care”: meet yoursealf, love yoursealf, be kind to yoursealf, and embrace yoursealf. While the 55 pastel-color illustrations and their captions are certainly cutesy, they are never nauseatingly so. By turns they are funny, heartwarming and, occasionally, right on the nose. And for all its pinniped delights, I’m confident that Wang’s 121,000 Instagram followers will stand by Seal the same way that Seal has stood by them. ∎

Jack Hargreaves is a London-based translator from East Yorkshire. His published and forthcoming full-length works include Winter Pasture by Li Juan (2020) and Seeing by Chai Jing (2020), co-translated with Yan Yan; I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan (2025); and A Man Under Water by Xiaoyu Lu (2026). He occasionally contributes to Paper Republic.