If only all China memoirs could include the kind of caveat emptor with which Ellen La Motte begins her 1919 travelogue, Peking Dust:

Two classes of books are written about China by two classes of people. There are books written by people who have spent the night in China, as it were, superficial and amusing, full of the tinkling of temple bells; and there are other books written by people who have spent years in China and who know it well, — ponderous books, full of absolute information, heavy and unreadable. This book falls into neither of these two classes, except perhaps in the irresponsibility of its author. It is compounded of gossip, — the flying gossip or dust of Peking. Take it lightly; blow off such dust as may happen to stick to you.

Despite the warning, it is rather hard to imagine much dust — Peking or otherwise — sticking long to this particular China author.

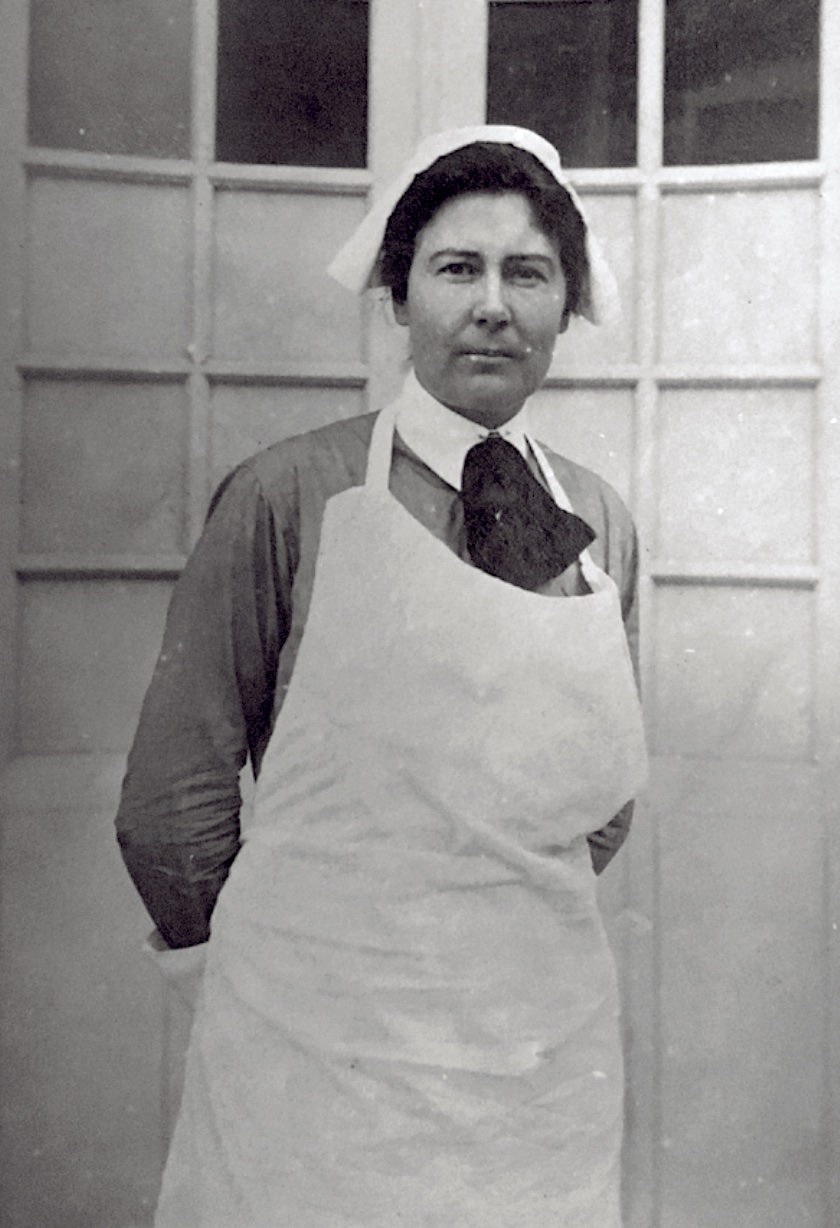

Born in 1873 in Kentucky, Ellen Newbold La Motte spent much of her early life and education in the Chesapeake Bay area and Northern Virginia. One of her aunts had married into the wealthy Dupont family of Delaware. Her cousin, Alfred I. Dupont, would be a lifelong mentor and source of financial support when she left behind debutante society for an unconventional life as a nurse, writer and activist. As her biographer Lea Williams notes in Ellen N. La Motte: Nurse, writer, activist, by the time La Motte arrived in Beijing in 1916, she had already served as one of the first female health officials in the city of Baltimore; marched with suffragettes in America and Britain; waited out air raids crouched in a Paris stairwell with Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso; and been labeled a subversive agent by both the British government and the U.S. Post Office. She was a peripatetic traveler, a seeker of causes and a fiendishly keen intellect that refused to suffer fools or hypocrisy.

Few foreigners in Beijing have left as candid a literary mark on the city as Ellen La Motte.

La Motte’s wanderlust, and her quest for new challenges, first took her to Europe. At the outset of World War I, she volunteered as a nurse at a French military field hospital in Belgium. In her forties, with 15 years of medical experience, nothing prepared La Motte for the horrors she witnessed in the trauma tents of the Western front. She channeled her outrage through her writing. Published in 1916, Backwash of War is a set of loosely fictionalized vignettes that describe the effects of war on the human body, from limbs and torsos blown apart to young men ravaged by venereal disease. The book was a sensation when it first appeared but was soon blacklisted in England and France for hurting morale during the war effort, and later banned in the U.S., impounded by the Postmaster General as subversive.

(Manchester University Press/public domain)

La Motte’s prose in Backwash of War and Peking Dust is sparse but descriptive, with an economy of words that recalls Ernest Hemingway. The connection is perhaps not a coincidence. While staying in Paris, La Motte was, like Hemingway, a regular at the apartments of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas; Stein had been a classmate of hers at Johns Hopkins Hospital Training School for Nurses, before dropping out to become a writer. It was also likely Stein who introduced La Motte to Emily Crane Chadbourne, an art collector from a wealthy Chicago family. Ellen and “Em” remained romantic partners (conventions of the age referred to the women as “long-time companions”) until La Motte’s death.

It was a chilly night in Paris, curled up by a fire reading of the wonders of Asia, that inspired La Motte and Chadbourne to travel to China, Japan and Southeast Asia. Stepping onto the train platform at Beijing station in October 1916, La Motte was swept away by China and fell under the spell of the city and its history. She writes:

If you have ever stayed here long enough to fall under the charm and interest of this splendid barbaric capital, if you have once seen the temples and glorious monuments … all other parts of China seem dull and second rate.

Peking Dust is not just a dusty travelogue of “tinkling bells.” La Motte frequently offers her sharp opinions and views on the issues of the day: the annexation of the Laoxikai section of Tianjin into the French concession; corruption in the Chinese government abetted by foreign advisors; governments, business interests, and the question of whether China will join in World War I.

Chapter by chapter, La Motte could be seen as the literary ancestor of a group of writers who thrived, for a time, at the turn of the 21st century: the China blogger. In his introduction to the 2013 Camphor Press edition of Peking Dust, editor John Ross compares La Motte’s writings on China to “the twenty-first-century blog of a newly arrived Westerner; there are the clippings from the news with accompanying rants, the personal asides and confidences to the reader, and the cursory dismissals of her fellow foreigners.” (As somebody who wrote one of those blogs, I cringe thinking how accurate this description is.)

Among other traits that LaMotte finds at fault in her fellow foreigners, none angered her more than the continuing scourge of the opium trade. At the time of her residence in Beijing, the Chinese government was in negotiations with British opium merchants to phase out the trade — an effort undermined by influential firms who relied on drug imports for their bottom line, officials who profited from the trade, and rampant corruption that extended all the way to the top in Beijing. She writes:

Oh, disabuse your mind of the fact that China is a sovereign state! She is bound hand and foot, helpless, mortgaged up to the hilt. Every foreigner in China knows it, and the Chinese know it themselves only too well. It seems such a farce to give them the courtesy title of sovereignty … I can also tell you that every one over here — all the foreigners I mean — laugh at China and ridicule her and make fun of her weak, corrupt government, of her inertia and helplessness, and think what she gets is good enough for her.

Despite her deserved reputation as an activist and supporter of progressive causes, some of La Motte’s beliefs do reflect the times, and her upbringing. Her views of public health were often unsympathetic to the poor. In her book The Tuberculosis Nurse, published in 1914, La Motte advocates removing suspected tuberculosis carriers from their homes and placing them in enforced quarantine, coming off as more Nurse Ratchet than Florence Nightingale. Some of her portrayals of people of color, including of Chinese people in Peking Dust, are racist. One oddly inserted joke, written in black vernacular and using a particular epithet, is jarring in the context of a work that so often expresses sympathy for the oppression of the Chinese people, and an open hostility to the institutions of Western imperialism and white privilege.

In the eradication of the opium trade and the treatment of opium addiction LaMotte found her new calling and purpose. She followed up Peking Dust with a collection of short fiction, Civilization: Tales of the Orient (1919), and a series of non-fiction books, polemics and pamphlets reflecting her new crusade: Opium Monopoly (1920), Ethics of Opium (1922), Snuffs and Butters (1925) and Opium in Geneva (1929). In 1930, the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek, who had taken control of the country three years earlier and restored some semblance of central authority, recognized La Motte’s contributions with the Lin Tse Hsu Memorial Medal — named for the incorruptible Guangzhou official who had seized and burned the foreign stocks of opium just before the start of the first Opium War in 1840.

La Motte didn’t stay in China long. She spent October and November of 1916 in Beijing, wintered in Southeast Asia, and returned for a month in early spring. She continued to travel (Europe, Egypt, Ethiopia) and write well into her sixties, before settling down with Chadbourne in Washington, DC. She died in 1961 at the age of 88; her partner died three years later. Like many sojourners before and after, her time in China left a deep impression. But few foreigners in Beijing have left as candid a literary mark on the city as Ellen La Motte. ∎

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and historian who taught late imperial and modern Chinese history in Beijing for over two decades. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis, and is the co-host of the podcast Barbarians at the Gate.